Where Things Thrive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York City City Guide

New York City City Guide Quick Facts Country USA Currency US Dollar $ 100 cents makes $1 Language English Population 18,498,000 Time Zone GMT -5 or GMT -4 (March to November) Climate Summer Av Max 28°c Autumn Av Max 15°c Winter Av Max 5°c New York City’s Brooklyn Bridge at dusk Spring Av Max 15°c Introducing New York City What to See in New York City Capital of the world‟s financial, consumer and Architecture Interesting buildings include 50 cast-iron entertainment fields, New York is a city of towering buildings in SoHo District; the Jefferson Market Courthouse skyscrapers, bright neon lights and world-class museums. in Greenwich Village; the Flatiron Building; the New York It is one of the most dynamic cities on earth. It pulsates Public Library; Grand Central Terminal; the United Nations with life and has something to suit every taste. It headquarters, an international zone with its own post office comprises the five districts of Manhattan, the Bronx, and stamps; the Rockefeller Center; the Chrysler Building Queens, Brooklyn and Staten Island. It has over 6 000 with its gleaming stainless-steel spire. miles of streets, so walking isn‟t an easy option! Use the buses, subways and unique yellow cabs. The Empire State Building is the tallest and most striking skyscraper. Climb the Empire State Building„s 1576 steps Chinatown and Little Italy on the Lower East Side are from the lobby to the observation deck on the 86th floor. colourful neighbourhoods adding to the cosmopolitan flavour of The Big Apple. -

Fran Delgorio [email protected] 212.421

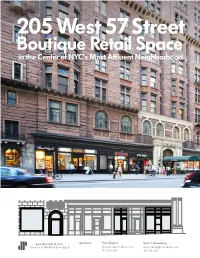

resnick.nyc Fran Delgorio Brett S. Greenberg [email protected] [email protected] 212.421.1300 212.421.1300 The Center of It All • Located in the heart of Manhattan’s most affluent neighborhood, on 57 Street at 7th Avenue and at the base of the historic Osborne apartment building • Surrounded by plentiful Citi Bike stations • Less than one block from the new Nordstrom flagship store and across the street from Carnegie Hall • Nearby Columbus Circle retailers bring high foot traffic to the surrounding neighborhood • Surrounded by Manhattan’s most luxurious residential apartments and five-star hotels, including Park Hyatt and JW Marriot Essex House Neighborhood Pulse* • Area population of 43,000 • Average household income of $185,000 • $1.24 billion in total retail expenditure • 46,000 total office population, 97% professional workers • 535 company headquarters • Median home sales at $9.8 million • 7,400 hotel rooms Neighboring Businesses P Citi Bike Station P Parking Garage 37 RESTAURANT & DINING ARTS & CULTURE 1 Chipotle Mexican Grill 30 Carnegie Hall 3 2 Starbucks 31 The Art Students League 3 Paris Baguette 32 Museum of Art and Design 8th Avenue 4 Pret A Manger C 1 o 2 36 lu 5 Joe & The Juice RETAIL 32 m bu 6 Redeye Grill 33 Wells Fargo Bank P s C 35 ircle 7 Trattoria Dell’Arte 34 Duane Reade 40 8 Brooklyn Diner USA 35 Nordstrom Flagship Store 34 Broadway 9 Wolf at Nordstrom NYC 36 CVS Pharmacy 33 10 9Ten 37 The Shops at Colmbus Circle 11 11 Maison Kayser 38 Frank Stella Clothiers 5 12 41 Grom 39 Ascot Chang 12 13 13 Marea -

Nyc & Company Invites New Yorkers to Discover Times

NYC & COMPANY INVITES NEW YORKERS TO DISCOVER TIMES SQUARE NOW AND REVITALIZE THE CROSSROADS OF THE WORLD ——Earn Up to $100 Back and Enjoy Savings at Iconic Hotels, Museums, Attractions, Restaurants and More at Participating “All In NYC: Neighborhood Getaways” Businesses —— New York City (October 26, 2020) — NYC & Company, the official destination marketing organization and convention and visitors bureau for the CONTACTS five boroughs of New York City, is inviting New Yorkers to take an “NYC- Chris Heywood/ cation” at the Crossroads of the World, in the heart of Times Square. With Britt Hijkoop many deals to take advantage of, now is an attractive time to take a staycation NYC & Company 212-484-1270 in Times Square and the surrounding blocks, to visit some of the most iconic [email protected] hotels, attractions, museums, shopping and dining that Midtown Manhattan has to offer. Mike Stouber Rubenstein 732-259-9006 While planning an “NYC-cation” in Times Square, New Yorkers are [email protected] encouraged to explore NYC & Company’s latest All In NYC: Staycation DATE Guides and earn up to $100 in Mastercard statement credits by taking October 26, 2020 advantage of the All In NYC: Neighborhood Getaways promotion, NYC & Company’s most diverse, flexible and expansive lineup of offers ever, with FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE more than 250 ways to save across the five boroughs. "Now is the time for New Yorkers to re-experience Times Square… for its iconic lights, rich history, hidden gems, world-renowned dining and unique branded retail and attractions. While we can’t travel out, we should seize this moment and take advantage of the Neighborhood Getaway deals to book a hotel and play tourist with an ‘NYC-cation’ at the Crossroads of the World,” said NYC & Company President and CEO Fred Dixon. -

200 West 57Th Street

200 West 57th Street New York, NY 10019 At 7th Avenue Prime Retail Spaces Available In the Heart of Midtown 1,514 SF Ground Floor 200 West 57th Street Ceiling Height: 14’ 3” 1,641 SF Ground Floor Frontage: 22’ on 57th Street 1,514 SF 1,641 SF Ceiling Height: 18’ • Steps from the new Nordstrom flagship store slated to open in 2018, 210-key Park Hyatt hotel and luxury 92-unit condominium ONE57 developments 7th Avenue West 57th Street • Located at the crossroads of major north-south and cross-town thoroughfares • Retail building tenants include 58TH STREET Fresh & Co, Fed Ex, and Trattoria Dell’Arte N BARBER PETROSSIAN TE PHARMACY • Surrounded by select hotels including the BOUTIQUE Y COFFEE ALIA Y S PARK HYATT N Plaza Hotel, Ritz-Carlton Hotel, Park Hyatt T ORK L CHOCOLA NEW YORK WBERR Y New York, Hotel Pierre, Park Savoy Hotel, AR CAFE TE OPENING 2018 ALISBUR Dream New York, and Peninsula Hotel QUALITY IT STRA FRESH & CO BERGDORF GOODMA THE STUDENT LEAGUE OF NEW S EUROPA HO 57TH STREET • Directly across from Carnegie Hall, near N Y M Columbus Circle, Central Park, Lincoln TER FedEx AN OR’S CLEANERS RUE 57 Center, Russian Tea Room, Rockefeller 200 N N DINER COHEN’S THEA JEWELR VENUE VENUE VENUE TRATORIA TEA ROO NAILS Center, and Radio City Music Hall LY DELL’ARTE DIRECT THE RUSSIA AGE BOOKS GUILD Z CHEMISTS KENJO METROPOLIT SMYTHSO 5TH A 5TH 6TH A 6TH 7TH A 7TH VINT BROOK RED EYE GRILL 56TH STREET BROADW E N N AN Y AR TT Q CHRISTMAS CHOP’T F ON Y COTTAGE TRE CLUB NY CIT CENTER AY HAIR SALO AGE ST INST R STEAKHOUS MANHA UNCLE JACK’S PARK CAFE THEA NAILS ST DELI LILLA SKIN CARE HARR W 55TH STREET New York New York 200 WEST 57TH STREET ENUE AV H 7T 1,514 SF Ceiling Height: 14’ 3” 1,641 SF Ceiling Height: 18’ Frontage: 22' 57TH STREET For leasing information, please contact Randall Briskin X218 | [email protected] 7 Penn Plaza, New York, NY 10001 T 212 279 7600 www.feilorg.com 3/18. -

Restaurant Offers

RESTAURANT OFFERS 117 W. 58th Street (between 6th and 7th Avenues) Offer arranged at Concierge desk Or in person (credential required) www.ninostuscany.com (212) 757-8630 50% off menu for players 25% off menu for all other credential holders This Upper Midtown gem is another winner for restaurateur Nino Selimaj. Featuring the hospitality and class that patrons have come to expect from Nino, Nino’s Tuscany is an excellent choice for all diners. Featuring a Tuscan inspired menu of Italian classics, along with many fine dishes featuring wild game, Nino’s Tuscany is a unique and high end option in the Italian dining scene. 235 Park Avenue S. (at 19th Street) Offer arranged at Concierge desk Or in person (credential required) www.citycrabnyc.com (212) 529-3800 25% off menu City Crab, proudly serving New York City’s freshest seafood since 1993. The East River at 30th Street Offer arranged at Concierge desk Or in person (credential required) www.thewaterclub.com (212) 683-3333 25% off menu The Water Club serves classic American cuisine in an elegant setting with sweeping river views. Enjoy refreshing cocktails and light bites upstairs at the rooftop tiki bar, The Crow's Nest. Located on the East River between 28th and 32nd Street in New York City. 90 East 42nd Street Offer arranged at Concierge desk Or in person (credential required) www.pershingsquare.com (212) 286-9600 25% off menu Pershing Square offers casual American cuisine in a bustling classic bistro environment. Conveniently located on 42nd Street directly across from New York's famous Grand Central Terminal’s main entrance and underneath the Park Avenue Viaduct. -

The Bloom Is on the Roses

20100426-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 4/23/2010 7:53 PM Page 1 INSIDE IT’S HAMMERED TOP STORIES TIME Journal v. Times: Story NY’s last great Page 3 Editorial newspaper war ® Page 10 PAGE 2 With prices down and confidence up, VOL. XXVI, NO. 17 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM APRIL 26-MAY 2, 2010 PRICE: $3.00 condo buyers pull out their wallets PAGE 2 The bloom is on the Roses Not bad for an 82-year-old, Adam Rose painted a picture of a Fabled real estate family getting tapped third-generation-led firm that is company that has come a surpris- for toughest property-management jobs known primarily as a residential de- ingly long way from its roots as a veloper. builder and owner of upscale apart- 1,230-unit project.That move came In a brutal real estate market, ment houses. BY AMANDA FUNG just weeks after Rose was brought in some of New York’s fabled real es- Today, Rose Associates derives as a consultant—and likely future tate families are surviving and some the bulk of its revenues from a broad just a month after Harlem’s River- manager—for another distressed are floundering, but few are blos- menu of offerings. It provides con- A tale of 2 eateries: ton Houses apartment complex was residential property, the vast soming like the Roses.In one of the sulting for other developers—in- taken over, owners officially tapped Stuyvesant Town/Peter Cooper Vil- few interviews they’ve granted,first cluding overseeing distressed prop- similar starts, very Rose Associates to manage the lage complex in lower Manhattan. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 93, 1973-1974, Trip

Segovia, appearing ccc/5 s: Andres in recital this month Oa. < DC LU LL LU < lb Les Hooper, traveler through a crowded ol' world. United dedicates ^riendshq) Sendee. Rooiiqr747aiidDC-10 Friend Sh4>s. Flying New York to the west, why crowd yourself? United people to help you along the way. And extra wide Stretch out. Lean back. And try on a roomy 747 or DC-10 aisles, so you can walk around and get friendly yourself. for size. YouVe also a wide range of stereo entertainment. Another reason more people choose the friendly And a full-length feature film on selected flights skies than any other airline in the land. ($2.00 in Coach). A daily 747 to Los Angeles, and roomy DC-lO's to So call United Air Lines at (212) 867-3000, or your Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Denver and Travel Agent, and put yourself aboard our giant Cleveland. Friend Ships. You can't go west in a bigger way. Only United flies the Friend Ship with so many extras. Extra room to stretch out and relax. Extra friendly The friendly skies ofyour land. Unitedh 747's & DClOb to the West Partners in Travel with Western International Hotels. "FOM THE ELIZABETH ARDEN SALON Our idea. Quick. Simple. Color-coded to be fool-proof. Our System organizesyour skin care by daily skin care soyou can cleanse, skin type, simplified. tone and moisturize more efficiently. And effectively. Introducing ¥or instance, Normal-to-Oily skin The Personal can have its own Clarifying Astringent. Normal-to-Dry skin its own Fragile Skin Care System Skin Toner No matter which skin type have, find a product by Elizabeth Arden. -

Medical School Bleeds Yeshiva U

20141215-NEWS--0001-NAT-CCI-CN_-- 12/12/2014 7:02 PM Page 1 STAFFERS AT MOSCOW57 have a good reason to sing CRAIN’S® NEW YORK BUSINESS PAGE 21 VOL. XXX, NO. 50 WWW.CRAINSNEWYORK.COM DECEMBER 15-21, 2014 PRICE: $3.00 Medical school bleeds Yeshiva U University pressured to sell real estate and end Einstein College’s $100M annual losses BY BARBARA BENSON A deal meant to stabilize the finances of money-losing Albert Einstein Col- lege of Medicine of Yeshiva University may be derailed,putting more financial pressure on the university to address losses dating back to a reported $100 million hit from former trustee Bernard Madoff ’s fraud scheme. Hobbled with a junk-bond-status credit rating, JUNK-BOND-B3 Yeshiva University STATUS CREDIT officials have spent RATING for recent years selling Yeshiva University off real estate, debt completing a $175 million private placement to in- ESTIMATED$150M Mayor de Blasio: vestors, and strik- ANNUAL DEFICIT ing the now-falter- for Yeshiva ing deal to create a University as of September joint venture be- 2014 tween Einstein and Montefiore Medical Center in 2/3 Year One the Bronx. SHARE OF newscom But last week, LOSSES from Albert Einstein Moody’s Investors College of The sky didn’t fall, but biz execs THE INSIDER Service issued a Medicine credit-rating re- remain wary of City Hall agenda port that suggested More than horses Yeshiva’s restructuring efforts may not produce results quickly enough.Citing BY ANDREW J. HAWKINS at stake for activist a potential cash crunch, the report raised “the possibility that Yeshiva This time last year, many business owners feared that the impending could exhaust unrestricted liquidity mayoralty of Bill de Blasio, an unabashed populist eyeing the bulging BY CHRIS BRAGG before successfully addressing its deep pockets of the 1%, would doom New York City. -

Robb Report Holiday Hot List List

BY EVE RETT POTTER he holiday season in Manhattan is a heady time for shoppers, T show lovers, and anyone who likes to revel in the merryfeeling in the air. Cheerful window displays at Bergdorf Goodman, Sales Fifth Avenue, and Henri Bendel light the streets. Holiday markets fill with tourists and the high-intensity energy ofthe city. From the 30,000 lights adorning the great tree at Rockefeller Center to The Nutcracker playing at Lincoln Center, the holidays are indeed the high point ofthe year in New York. The Surrey (thesurrey.com) on the Upper East Side, a very exclusive and very private hotel on one ofthe city's toniest blocks, will be trimmed in Sotheby's Diamonds with an exclusive gift collection on display (see page 12). The Four Seasons Hotel New York / (fourseasons.com) in midtown, where it's high style on Park Avenue, has enlisted its head chifand pastry chifto teach and feed guests bifore showing them to choice seats for the Rockefeller tree lighting (see page 14). Downtown, the Crosby Street Hotel (firmdalehotels.com)-in the heart ofstylish SoHo and colorfully decorated by London's Kit Kemp of Firmdale Hotels-is planning an elaborate English Christmas Day meal complete with beif Wellington and chocolate cranberry pudding cake (see page 14). To find out what else is going on in the city during the holidays, we spoke with the experts on each neighborhood. Director of sales North America at the Crosby Narell Devine, Les Clifs d'Or chif concierge at the Surrey Lorena Ringoot, and Four Seasons concierge agent Tina McLelland share their personal recommendations in the following insider's guide to the best ofthe season. -

Hospitality & Retail Project Experience

1 Hospitality & Retail Project Experience Hotel Projects Baccarat 53rd Street Hotel and Residences| New York, NY Architect: SOM Edition Hotel at 701 7th Avenue | New York, NY Architect: PBDW Trump SoHo Hotel Condominium| New York, NY Architects: Handel Architects (base building) / The Rockwell Group (interiors) The Hotel at Destiny USA | Syracuse, NY Architect: Cooper Carry InterContinental New York Times Square Hotel – LEED Certified | New York, NY Architect: Gensler Mandarin Oriental Hotel at Time Warner Center| New York, NY Architects: Brennan Beer Gorman (now HOK) The Mark Hotel and Residences | New York, NY Architect: SLCE Architects W Hotel | Hoboken, NJ Architect: Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects (now Gwathmey Siegel Kaufman Architects) Mandarin Oriental Hotel | Miami, FL Architect: RTKL Associates Wyndham Hotel at Port Imperial Building 4/5 | Weehawken, NJ Architect: Brennan Beer Gorman (now HOK) The Diplomat Hotel Resort & Convention Center | Hollywood, FL Architect: Nichols Brosch Sandoval Gaylord Palms Resort and Convention Center | Orlando, FL Architect: The Hnedak Bobo Group Grande Lakes Resort | Orlando, FL Architect: Smallwood, Reynolds, Stewart, Stewart and Associates, Inc. Marriott Convention Center Headquarters Hotel | Washington, DC Architect: Rafael Vinoly Architects 2 Flatotel at 135 West 52nd Street | New York, NY Architect: Costas Kondylis & Partners (now Goldstein Hill & West Architects) J.W. Marriott Grand Rapids (Alticor Hotel) | Grand Rapids, MI Architect: Goettsch Partners Al Ain Wildlife Reserve - LEED -

Vornado Realty Trust Form 10-K405

VORNADO REALTY TRUST FORM 10-K405 (Annual Report (Regulation S-K, item 405)) Filed 03/11/02 for the Period Ending 12/31/01 Address 888 SEVENTH AVE NEW YORK, NY 10019 Telephone 212-894-7000 CIK 0000899689 Symbol VNO SIC Code 6798 - Real Estate Investment Trusts Industry Real Estate Operations Sector Services Fiscal Year 12/31 http://www.edgar-online.com © Copyright 2015, EDGAR Online, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Distribution and use of this document restricted under EDGAR Online, Inc. Terms of Use. VORNADO REALTY TRUST FORM 10-K405 (Annual Report (Regulation S-K, item 405)) Filed 3/11/2002 For Period Ending 12/31/2001 Address 888 SEVENTH AVE NEW YORK, New York 10019 Telephone 212-894-7000 CIK 0000899689 Industry Real Estate Operations Sector Services Fiscal Year 12/31 EXHIBIT INDEX ON PAGE 137 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D. C. 20549 FORM 10-K |X| ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended: DECEMBER 31, 2001 Or | | TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from ________________ to ________________ Commission File Number: 1-11954 VORNADO REALTY TRUST (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) MARYLAND 22-1657560 ------------------------------- ---------------------- (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification Number) 888 SEVENTH AVENUE, NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10019 ---------------------------------------- ---------- (Address -

Fran Delgorio [email protected] 212.421

resnick.nyc Fran Delgorio Brett S. Greenberg [email protected] [email protected] 212.421.1300 212.421.1300 The Center of It All • Located in the heart of Manhattan’s most affluent neighborhood, on 57 Street at 7th Avenue and at the base of the historic Osborne apartment building • Surrounded by plentiful Citi Bike stations • Less than one block from the new Nordstrom flagship store and across the street from Carnegie Hall • Nearby Columbus Circle retailers bring high foot traffic to the surrounding neighborhood • Surrounded by Manhattan’s most luxurious residential apartments and five-star hotels, including Park Hyatt and JW Marriot Essex House Neighborhood Pulse* • Area population of 43,000 • Average household income of $185,000 • $1.24 billion in total retail expenditure • 46,000 total office population, 97% professional workers • 535 company headquarters • Median home sales at $9.8 million • 7,400 hotel rooms Neighboring Businesses P Citi Bike Station P Parking Garage 37 RESTAURANT & DINING ARTS & CULTURE 1 Chipotle Mexican Grill 30 Carnegie Hall 3 2 Starbucks 31 The Art Students League 3 Paris Baguette 32 Museum of Art and Design 8th Avenue 4 Pret A Manger C 1 o 2 36 lu 5 Joe & The Juice RETAIL 32 m bu 6 Redeye Grill 33 Wells Fargo Bank P s C 35 ircle 7 Trattoria Dell’Arte 34 Duane Reade 40 8 Brooklyn Diner USA 35 Nordstrom Flagship Store 34 Broadway 9 Wolf at Nordstrom NYC 36 CVS Pharmacy 33 10 9Ten 37 The Shops at Colmbus Circle 11 11 Maison Kayser 38 Frank Stella Clothiers 5 12 41 Grom 39 Ascot Chang 12 13 13 Marea