Tagore in Sindhi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shah a Bdul L Atif B Hitai C Hair

ﻛﻼﭼﻲ ﺗﺤﻘﻴﻘﻲ ﺟﺮﻧﻞ Kalachi Research Journal Dr. Ravi Prakash Tekchandani TRANSLATIONS OF TAGORE'S WRITINGS IN SINDHI : A BRIEF SURVEY The present paper is classified into the following four sec- tions: 1. Sindhi: A Stateless Language in India with its location in Sindh, Pakistan 2. Cultural Relations between Bengal and Sindh 3. Gurudev Tagore's Visit to Sindh 4. Translations of Tagore's Writings in Sindhi Sindhi: A Stateless Language in India with its location in Sindh, Pakistan: Sindhi is one of the main literary languages of India, rec- ognized in the eighth schedule of Indian constitution. It was given place in the constitution on 10th April 1967, after constant and justified demand of the Sindhi community in India after inde- pendence. It belongs to the western group of modern Indo Aryan languages. The Sindhi language geographically has its origin and historical evolution in the region of the lower Indus valley, which coincides broadly with the present Sindh province in Pakistan. It shows dialectal variations in that region. Vicholi, the dialect of middle part of Sindh has achieved the status of standard literary language. Linguistically, Kutchhi, the language spoken in Kutch district of Gujarat in India and Dhataki, the language spoken in the western Rajasthan adjacent to the border of Sindh, are consid- ered dialects of the Sindhi language, having admixture of Gujarati and Rajasthani respectively. But, speakers of these dialects iden- tify themselves culturally with the local people of these provinces in India. Shah Abdul Latif Bhitai Chair After the independence of India in 1947, about twelve lakhs of Sindhi - speaking Hindus, compelled by circumstances of that period, migrated from Sindh and got spread out in different provinces of India. -

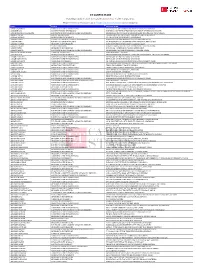

ET CAMPUS STARS Following Candidates Have Been Shortlisted for Phase 2 of ET Campus Stars

ET CAMPUS STARS Following candidates have been shortlisted for Phase 2 of ET Campus Stars. Please feel free to reach out to us at [email protected] in case of any query. Name Branch COLLEGE NAME AABITHA JASMINE COMPUTER SCIENCE ENGINEERING P.T.R. COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY, MADURAI AADARSH DAS MANUFACTURING TECHNOLOGY NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF FOUNDRY AND FORGE TECHNOLOGY, RANCHI AADI MANIKANTA PADAMATA ELECTRONICS AND COMMUNICATION ENGINEERING DHANEKULA INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERINGAND TECHNOLOGY, VIJAYAWADA AAKASH GUPTA MARINE ENGINEERING INDIAN MARITIME UNIVERSITY - KOLKATA CAMPUS, KOLKATA AAKASH JAGWANI INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY L.D COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, AHMEDABAD AAKASH RAWAT ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS ENGINEERING MAHARAJA AGRASEN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, DELHI AAKASH SINHA ELECTRICAL AND ELECTRONICS SIR M VISVESVARAYA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, BENGALURU AAKASH THAPER MECHANICAL ENGINEERING NORTHERN INDIA ENGINEERING COLLEGE, DELHI AAKASH TIWARI CIVIL ENGINEERING GREATER NOIDA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, GREATER NOIDA AAKRIT PATEL MECHANICAL ENGINEERING BITS PILANI - HYDERABAD CAMPUS, HYDERABAD AAKRITI MEHTA ELECTRONICS AND COMMUNICATION ENGINEERING GOVERNMENT WOMEN ENGINEERING COLLEGE, AJMER AALEKHYA VASANTAVADA CHEMICAL ENGINEERING SRM UNIVERSITY, CHENNAI AANCHAL JAIN INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY SHRI RAMSWAROOP MEMORIAL GROUP OF PROFESSIONAL COLLEGES, LUCKNOW AAROHI AGARWAL COMPUTER SCIENCE ENGINEERING KIET GROUP OF INSTITUTIONS, GHAZIABAD AAROHI SRIVASTAVA COMPUTER SCIENCE ENGINEERING KIET GROUP OF INSTITUTIONS, GHAZIABAD AARON MATHEWS -

L45200mh1999plc118949 -11-Iepf-2

Note: This sheet is applicable for uploading the particulars related to the unclaimed and unpaid amount pending with company. Make sure that the details are in accordance with the information already provided in e‐form IEPF‐2 Date Of AGM(DD‐MON‐YYYY) CIN/BCIN L45200MH1999PLC118949 Prefill Company/Bank Name MAHINDRA LIFESPACE DEVELOPERS LIMITED 30‐JUL‐2018 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 1913334.00 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0.00 Sum of matured deposit 0.00 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0.00 Sum of matured debentures 0.00 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0.00 Sum of application money due for refund 0.00 Redemption amount of preference shares 0.00 Sales proceed for fractional shares 0.00 Validate Clear Proposed Date of Investor First Investor Middle Investor Last Father/Husband Father/Husband Father/Husband Last DP Id‐Client Id‐Account Amount Address Country State District Pin Code Folio Number Investment Type transfer to IEPF Name Name Name First Name Middle Name Name Number transferred (DD‐MON‐YYYY) NILESH N PUROHIT NATVARLAL PUROHIT 202 AMBA ASHISH 2ND FLOOR OPP AINDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400066 P40157581 Amount for unclaimed and un 6.00 03‐NOV‐2021 PETER M J M M JOSEPH C/O GLADWIN THOMAS PUTHENPAR INDIA KERALA COCHIN 682008 P40157697 Amount for unclaimed and un 60.00 03‐NOV‐2021 SWETHA SUNIL RAIKAR SUNIL PUSHPAVIHAR SOCIETY SHANTI NAGAINDIA MAHARASHTRA THANE 401102 P40158189 Amount for unclaimed and un 60.00 03‐NOV‐2021 CHANDRAKANT SHET XXXXXX LATE S GANAPATHISHET CHANDRA JEWELLERS CAR STREET MINDIA -

Contribution of Sindh in Freedom Movement of India

2013 Contribution of Sindh in Freedom Movement of India This is the translation from the Hindi Book by Prem Tanwani “Swatantra Sangram Aur Sindh Ka Yogdan” Translated by: Deepak Ramchandani CONTRIBUTION OF SINDH IN MOVEMENT OF INDEPENDENCE OF INDIA Author Prem Motiram Tanwani B-28, Galaxy Residence, Amlidih , Raipur (Chattisgadh ) Mobile-9301179876 Translated By: Deepak Ramchandani S.D.B.90, Adipur-Kachchh, Pin-370205 M-9426321521, 02836-262275 2 From My Pen: I started reading history at the age of 45 years; most of the books I read were issued from N.R.Malkani library at Adipur. One day I got a book by Prem Motiram Tanwani “Swatantra Sangram Aur Sindh Ka Yogdan” I read this and shared my views with my wife that this book is worth translating into English, so that our generation which does not read Hindi could read the translated version. My family lives in Adipur and I am posted at Gandhinagar in Water Supply Board as Executive Engineer (Civil), I also shared the same with my colleagues and also narrated some important chapter of Parcho Vidhyarthi. But the question was of availability of time. On 17th May 2013 I encountered with an accident and was injured on head, skull and teeth, I proceeded on medical leave, this had given me opportunity of passing time during rest period. I spoke to the author Mr. Prem Tanwani on his mobile phone and got his permission and blessing. I am neither scholar of Hindi nor English as being technocrat there is less use of English in our Job, so the translation is in simple language. -

CIN Company Name Date of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY)

CIN L99999MH1937PLC002726 Company Name MUKAND LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 13-AUG-2014 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of matured deposit 19882000 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0 Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husband Father/Husba Father/Husband Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Proposed Date of First Name nd Middle Last Name Securities Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF Name (DD-MON-YYYY) 1 KABIR MANGLANI KABIR MANGLANI E9 SHANTI NIKETAN,OPP RAILWAY INDIA MAHARASHTRA THANE 400603 A57020 Amount for matured 45000 01-Apr-2015 STATION,THANE EAST, deposits 2 RAMJI M DAVE RAMJI M DAVE 130/32 APOLLO STREET,GREAT INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400001 F133003 Amount for matured 30000 06-Jul-2015 WESTERN BLDG 1ST FLR,R NO 25 deposits FORT MUMBAI, 3 KASTURI RAJNIKANT KOTHARI KASTURI RAJNIKANT KOTHARI ROOM NO 1415,3RD INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400019 F133095 Amount for matured 25000 09-Jul-2015 FLOOR,LILADHAR RATANSI BLDG,13 deposits LAXMINARAYAN LANE,MATUNGA CRL,MUMBAI, 4 FRENY GAEV KARANJIA FRENY GAEV KARANJIA 32,POSTAL COLONY,2ND INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400071 F133110 Amount for matured 25000 11-Jul-2015 FLOOR,CHEMBUR,MUMBAI, deposits 5 SHANTA RAMJI DAVE SHANTA RAMJI DAVE 130/32 APOLLO STREET,GREAT INDIA MAHARASHTRA MUMBAI 400001 F133190 Amount for matured 35000 15-Jul-2015 -

Details of Shareholders Unclaimed

HCC CONSECUTIVE OUTSTANDING PHY AND ELC RECORDS DIV PAY DATE 14-06-2011 SrNo Folio No/DPID ClientID 1st Holder Name 1st Joint Holder 2nd Joint Holder Add Line 1 Add Line 2 Add Line 3 Add Line 4 Add State Add Pincode Cumrrent Holding Amount_14JUN11 1 1201320000260366 SHIRODE ASHABAI VAMAN AT POST - SAYGAON TAL. CHALISGAON JALGAON 100 40.00 2 1203450000046694 MANISHA DANA Suvajit Dana B-1/135, KALYANI, NADIA 50 20.00 3 1201130000108840 ANITA MODI 410, A SILVER MALL, 8, RNT MARG, INDORE 40 16.00 4 1206850000006279 VIBHA RANGA W/O RAJESH RANGA KARMISAR ROAD OUT SIDE NATHUSAR GATE BIKANER 33401 40 16.00 5 1201060100100743 AMRISH NARESH SAXENA H. NO. 17 KABIR NIWAS MGIMS CAMPUS, SEWAGRAM WARDHA 42102 420 114.40 6 1201060100048428 Manoj Kumar Yadav Subhama Vihar Colony Lafagarh Gas , Godam Mangla Bilaspur 47751 100 40.00 7 IN30023910776917 RAHUL DUGGAL Shaveta Kapoor 15TH FLOOR SMSD PO BOX 3838 ABUDHABI, UAE 100000 600 240.00 8 IN30023911246780 OTTAKATH CHATHUNTAKAYIL KUTTIAMU P O BOX 61999 ABUDHABI U A E U A E 100000 600 240.00 9 HKA0009149 ASHOK KUMAR GULANI Padmaja Gulani 4/2 SINGLE STOREY RAMESH NAGAR NEW DELHI 110001 1000 400.00 10 HKB0040862 B S YADAV EDUCATION JCO HQ 502 AD GP (SP) C/O 56 APO DELHI 110001 500 400.00 11 HKC0264587 COLOMPRAKASH AWASTHY 11 CORPS PROVOST UNIT C/O 56 APO DELHI 110001 250 200.00 12 HKD0255276 DIPANKAR BANERJEE Sandhya Banerjee IDSA SAPRU HOUSE BARAKHAMBA ROAD NEW DELHI 110001 1500 1,200.00 13 HKK0006845 KARUNA SHARMA Raman Kumar H NO D-2 RANA PARTAP BAGH G T ROAD DELHI 110001 1000 800.00 14 HKN0259201 NEERJA -

CIN Company Name

CIN L99999MH1986PLC039199 Company Name APCOTEX INDUSTRIES LIMITED Date Of AGM(DD-MON-YYYY) 31-Jul-2014 Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 462280 Sum of interest on unpaid and unclaimed dividend 0 Sum of matured deposit 0 Sum of interest on matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of interest on matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 Sum of interest on application money due for refund 0 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husb Father/Husb Father/Husband Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Proposed Date of and First and Middle Last Name Securities Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF Name Name (DD-MON-YYYY) A BALASUBRA MANIAM ADINARAYAN B A 555 AGRAHARAM APCO000000000 Amount for unclaimed A CHETTIAR STREET ERODE INDIA TAMIL NADU 638001 0004693 and unpaid dividend 140.00 26-Jul-2017 369 65TH CROSS 5TH BLOCK A CHOKKA AVINASH RAJAJINAGAR APCO000000000 Amount for unclaimed LINGAM LINGAM BANGALORE INDIA KARNATAKA 560010 0018987 and unpaid dividend 250.00 26-Jul-2017 369 65TH CROSS A V 5TH BLOCK CHOKKALING AVANASHILI RAJAJINAGAR APCO000000000 Amount for unclaimed AM NGAM BANGALORE INDIA KARNATAKA 560010 0028332 and unpaid dividend 250.00 26-Jul-2017 13/653 MHB COLONY KHERNAGAR BANDRA (EAST) A BOMBAY GOVINDARAJ K M MAHARASHTRA APCO000000000 Amount for unclaimed AN ARUMUGAM INDIA INDIA MAHARASHTRA 400051 0039026 and unpaid dividend 500.00 26-Jul-2017 A Z/38 MIDDLE GOVINDASA STREET ALIVALAM MY ANNAMALAI TIRUVARUR TAMIL APCO000000000 Amount for unclaimed ANNAMALAI CHETTIAR NADU -

INDUSIND BANK LIMITED Sr No Name of the Shareholder Address

INDUSIND BANK LIMITED Sr No Name of the shareholder Address Pincode Folio/Dpid Client Id Remark Amount NO 179 LOYOLA COLLEGE HOSTEL, NUNGAMBAKKAM, Dividend on shares 1 A AMAL RAJESH CHENNAI, 600034 INDU0000000000148356 transferred to IEPF 1500.00 14/3 EAST ELLAI AMMAN KOIL STREET, RADHAKRISHNAN Dividend on shares 2 A B SRINIVASAN NAGAR, TIRUVOTTIYUR, MADRAS 600019 INDU0000000000075170 transferred to IEPF 750.00 Dividend on shares 3 A BALA KRISHNA 51 THILLAI NAGAR, KORATTUR, CHENNAI, 600080 INDU0000000000127060 transferred to IEPF 750.00 Dividend on shares 4 A C SUDHA BAI D NO 11-10-14 KOTA, HINDUPUR, ANANTAPUR DIST AP, 515201 INDU0000000000170840 transferred to IEPF 750.00 72 RAJA ANNAMALAI CHATTIAR RD, S B MISSION PO, Dividend on shares 5 A G GOVINDARAJULU COIMBATORE, 641011 INDU0000000000168408 transferred to IEPF 12000.00 D-1 KRISHI COTTAGES, 32 BAZULLA ROAD T NAGAR, Dividend on shares 6 A GAYATRI DEVI CHENNAI, 600017 INDU0000000000126406 transferred to IEPF 750.00 Dividend on shares 7 A K ALIMCHANDANI 5 Radhaswamy Colony, Sikh Village Extn, Secunderabad, 500009 INDU0000000000018997 transferred to IEPF 750.00 L I C OF INDIA ZONAL OFFICE, HOSHANGABAD ROAD MP Dividend on shares 8 A K MITTAL NAGAR, BHOPAL MP, 462011 INDU0000000000144948 transferred to IEPF 1500.00 AMBOOKEN HOUSE KONTHURUTHY, NEAR ST JOHN'S Dividend on shares 9 A L THOMAS CHURCH, COCHIN, 682013 INDU0000000000149510 transferred to IEPF 1500.00 DR NO 76/8/4-5/A, POPURI VARI STREET BHAVANIPURAM, Dividend on shares 10 A LATHA VIJAYAWADA, 520012 INDU0000000000124231 transferred -

Pg 4 Academics Divider

HASSARAM RIJHUMAL COLLEGE OF COMMERCE & ECONOMICS Affiliated to the University of Mumbai I/C Principal Mr. Parag Thakkar Vice-Principals Degree College Dr. Jehangir Bharucha Dr. Pooja Ramchandani Dr. Rajeshwari Ravi Librarian Superintendent Admin. Dr. Madhuri Tikam Ms. Jyoti Govindani Editor Graphic Design Ms Misha Bothra Ms Kamini Bahl www.hrcollege.edu 1 Contents 1 About Us 3 From the Desk of the I/C Principal 4 Academics 31 Lectures | Seminars | Workshops 58 Inter Collegiate Events 87 Beyond Academics 113 Internationalisation of HR 124 Student Enrichment 159 Our Achievers 169 Student Stories 197 Annual Prize Distribution Degree College 213 Annual Prize Distribution Junior College 222 Prize Distribution Lists Inside Front Cover - Recognitions Inside Back Cover - HR News 2 From the Desk of the I/C Principal Greetings from the Staff and Students and welcome to the vibrant world of H.R. College of Commerce and Economics affiliated to the University of Mumbai. Academic and co-curricular activities continue to be organized with great enthusiasm and commitment. The Prof Parag Thakkar previous year has been packed with guest lecture series, I/C Principal seminars, intercollegiate events - preparation, organization, participation and winning; signing of MOU's and much more. Our faculty members are always active in academic ventures and knowledge up-gradation. On the cultural front HR won most of the prominent inter- collegiate events. There is also a thrust on social responsibility in the college with students being encouraged to participate actively in Intelligence plus social work and build sensitivities to the world outside their college which is not as privileged. -

Alembic 2005-2006 Final

DETAILS OF UNPAID / UNCLAIMED DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2005-2006 AS ON 13TH AUGUST, 2012 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husb Father/Husb Father/Husband Address Country State District PINCode Folio Number of Investment Type Amount Proposed Date of and First and Middle Last Name Securities Due(in Rs.) transfer to IEPF Name Name (DD-MON-YYYY) A A JHAPIT S O REV MEDICAL OFFICER INDIA MAHARASHTRA 999999 ALEM00000000 Amount for unclaimed 28-Sep-2013 AMOS S HINDON RIVER 00032926 and unpaid dividend JHAPIT MILLS D C M DASNA GHAZIABAD U P 201001 150 A BALAJI NA NO 21 PADALI INDIA TAMIL NADU 607002 ALEMIN300214 Amount for unclaimed 28-Sep-2013 NAGAR 11495718 and unpaid dividend VANDIPALAYAM ROAD 100 A C QUILON MEDICAL INDIA KERALA 691001 ALEM00000000 Amount for unclaimed 28-Sep-2013 BALASUBRA ARUNACHAL STORE BIG BAZAR 00032869 and unpaid dividend MANIAN AM QUILON-691001 150 A LATE A C/O SHANKARA & INDIA KARNATAKA 560053 ALEM000000000 Amount for unclaimed 28-Sep-2013 GANAPATHY NARAYANA CO MUSLIM HALL 0032824 and unpaid dividend UDUPA UDUPA BUILDING AS CHAN STREET BANGALORE- 560053 450 A I NATHAN S ST.MARY'S INDIA KARNATAKA 560066 ALEM000000000 Amount for unclaimed 28-Sep-2013 AROCKIANA BUILDING MAIN 0032484 and unpaid dividend THAU ROAD CROSS WHITEFIELD BANGALORE- 560066 150 A S O S ST MARY'S BLDG INDIA KARNATAKA 560066 ALEM000000000 Amount for unclaimed 28-Sep-2013 IRUDAYANAT AROCHKIAN MAIN RD CROSS 0023514 and unpaid dividend HAN ATHAN WHITEFIELD P O BANGALORE- 560066 150 A J KRISHNAN NA NO 258 LEMIN INDIA TAMIL NADU 632513 ALEMIN3010802 -

Fall 2020 Honor Roll For

Fall 2020 University of Kansas honor roll. Not all students opt to have their names published. Name City State Country Award Grace Aaronson Overland Park KS USA School of Business Darian Abbott Chelsea OK USA School of Social Welfare Grace Abbott Naperville IL USA School of Business Leena Abdelmoity Overland Park KS USA College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Guled Abdi Lenexa KS USA College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Jamima Jasmin Abdul Hakkeem Georgetown, Penang MYS College of Liberal Arts & Sciences and School of Engineering Zakria Abdullahi Olathe KS USA College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Michael Abeita Hiawatha KS USA School of Architecture & Design Dhanushki Abeykoon Wichita KS USA School of Pharmacy Matt Abfall Mount Prospect IL USA School of Business Metages Abiyu Lenexa KS USA College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Ahmad Abouswid Sharjah UAE School of Engineering Eleazar Abraham Tangerang, Banten IDN College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Madeline Abrams Overland Park KS USA College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Mason Abshier Berryton KS USA School of Health Professions Qays Abu-Saymeh Olathe KS USA College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Emad Abughoush Manhattan KS USA School of Engineering Nadeen Abusalim Olathe KS USA School of Nursing Jessika Acharya Wichita KS USA College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Samrat Acharya Kathmandu NPL College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Jennifer Ackland Overland Park KS USA School of Nursing Alexander Acosta Hutchinson KS USA School of the Arts Diego Acosta Kansas City KS USA College of Liberal Arts & Sciences Melissa -

Global Sindhis Interview FINAL 01.Cdr

Kirat Babani Jawhrani: Babaniji, when and where were you born in Sindh? And also where were you educated in Sindh? Kirat: Dear Ram, I was born in the small village of Moro Lakho, District Nawab Shah on 3rd January, 1922. I also completed my primary education in the same village. Though our village didn't have a regular school, we learnt Sindhi from the cleric of a local mosque. Jawhrani: Tell us something about the business activity of your elders in Sindh? Kirat: We were shopkeepers and had a little bit of agricultural land in Sindh. My elders used to grow vegetables and fruits on it, which was sufficient for our own consumption. Jawhrani: Were you still in Moro Lakho at the time of partition? Kirat: It happened like this. Once a few dacoits came to our shop, and in the melee they killed my two uncles who were sleeping in the shop, and also set our shop on fire before fleeing from the scene. This tragedy forced our family to leave our ancestral village. Although the zamindar of the village tried his level best to persuade us to stay back, besides promising us that the dacoits would be brought to book for their heinous crimes, the tragedy left us with no other choice but to leave the village. Jawhrani: Can you tell us when did this crime occur? Kirat: Long before partition. We were only eleven Hindu families living in the village, but we never felt insecure. We had cordial relations with the local Muslims. Whenever our elders left us at home, they took care of us.