Country Policy and Information Note Cameroon: North-West/South-West Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

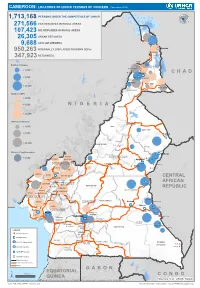

Page 1 C H a D N I G E R N I G E R I a G a B O N CENTRAL AFRICAN

CAMEROON: LOCATIONS OF UNHCR PERSONS OF CONCERN (November 2019) 1,713,168 PERSONS UNDER THE COMPETENCENIGER OF UNHCR 271,566 CAR REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 107,423 NIG REFUGEES IN RURAL AREAS 26,305 URBAN REFUGEES 9,688 ASYLUM SEEKERS 950,263 INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPs) Kousseri LOGONE 347,923 RETURNEES ET CHARI Waza Limani Magdeme Number of refugees EXTRÊME-NORD MAYO SAVA < 3,000 Mora Mokolo Maroua CHAD > 5,000 Minawao DIAMARÉ MAYO TSANAGA MAYO KANI > 20,000 MAYO DANAY MAYO LOUTI Number of IDPs < 2,000 > 5,000 NIGERIA BÉNOUÉ > 20,000 Number of returnees NORD < 2,000 FARO MAYO REY > 5,000 Touboro > 20,000 FARO ET DÉO Beke chantier Ndip Beka VINA Number of asylum seekers Djohong DONGA < 5,000 ADAMAOUA Borgop MENCHUM MANTUNG Meiganga Ngam NORD-OUEST MAYO BANYO DJEREM Alhamdou MBÉRÉ BOYO Gbatoua BUI Kounde MEZAM MANYU MOMO NGO KETUNJIA CENTRAL Bamenda NOUN BAMBOUTOS AFRICAN LEBIALEM OUEST Gado Badzere MIFI MBAM ET KIM MENOUA KOUNG KHI REPUBLIC LOM ET DJEREM KOUPÉ HAUTS PLATEAUX NDIAN MANENGOUBA HAUT NKAM SUD-OUEST NDÉ Timangolo MOUNGO MBAM ET HAUTE SANAGA MEME Bertoua Mbombe Pana INOUBOU CENTRE Batouri NKAM Sandji Mbile Buéa LITTORAL KADEY Douala LEKIÉ MEFOU ET Lolo FAKO AFAMBA YAOUNDE Mbombate Yola SANAGA WOURI NYONG ET MARITIME MFOUMOU MFOUNDI NYONG EST Ngarissingo ET KÉLLÉ MEFOU ET HAUT NYONG AKONO Mboy LEGEND Refugee location NYONG ET SO’O Refugee Camp OCÉAN MVILA UNHCR Representation DJA ET LOBO BOUMBA Bela SUD ET NGOKO Libongo UNHCR Sub-Office VALLÉE DU NTEM UNHCR Field Office UNHCR Field Unit Region boundary Departement boundary Roads GABON EQUATORIAL 100 Km CONGO ± GUINEA The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Sources: Esri, USGS, NOAA Source: IOM, OCHA, UNHCR – Novembre 2019 Pour plus d’information, veuillez contacter Jean Luc KRAMO ([email protected]). -

Phytochemical Screening and Antibacterial Activity of Medicinal Plants Used to Treat Typhoid Fever in Bamboutos Division, West Cameroon

Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science Vol. 5 (06), pp. 034-049, June, 2015 Available online at http://www.japsonline.com DOI: 10.7324/JAPS.2015.50606 ISSN 2231-3354 Phytochemical screening and antibacterial activity of medicinal plants used to treat typhoid fever in Bamboutos division, West Cameroon Tsobou Roger1, Mapongmetsem Pierre-Marie2, Voukeng Kenfack Igor3, Van Damme Patrick4 1Department of Plant Biology, University of Dschang, P.O.Box 67 Dschang, Cameroon; Department of Biological Sciences, University of Ngaoundéré, P.O.Box 454 Ngaoundéré, Cameroon. 2Department of Plant Production, Laboratory of Tropical and Subtropical Agriculture and Ethnobotany, 3Department of Biological Sciences, University of Ngaoundéré, P.O.Box 454 Ngaoundéré, Cameroon. 4Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Dschang; Dschang, Cameroon. ABSTRACT ARTICLE INFO Article history: This study was undertaken to document how typhoid is traditionally treated in Bamboutos division. For this Received on: 02/03/2015 purpose thirty eight plants species were selected. These plants underwent phytochemical screening and Revised on: 13/04/2015 antibacterial study using standard procedures. The antibacterial tests using agar well diffusion method and Accepted on: 30/04/2015 microdilution assay indicated that, all the thirty eight plant samples showed activity against S. typhi, while S. Available online: 27/06/2015 paratyphi A and S. paratyphi B reacted on fifteen and fourteen plants respectively. The highest zones of inhibition were obtained from Senna alata with diameter of 24, 22.5 and 20.5 mm against S. paratyphi A, S. Key words: paratyphi B and S. typhi respectively at 160 mg/ml concentration. The lowest MIC values 128 µg/ml was Phytochemical screening, exhibited by the extract of Vitex doniana against Salmonella paratyphi A. -

Understanding African Armies

REPORT Nº 27 — April 2016 Understanding African armies RAPPORTEURS David Chuter Florence Gaub WITH CONTRIBUTIONS FROM Taynja Abdel Baghy, Aline Leboeuf, José Luengo-Cabrera, Jérôme Spinoza Reports European Union Institute for Security Studies EU Institute for Security Studies 100, avenue de Suffren 75015 Paris http://www.iss.europa.eu Director: Antonio Missiroli © EU Institute for Security Studies, 2016. Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged, save where otherwise stated. Print ISBN 978-92-9198-482-4 ISSN 1830-9747 doi:10.2815/97283 QN-AF-16-003-EN-C PDF ISBN 978-92-9198-483-1 ISSN 2363-264X doi:10.2815/088701 QN-AF-16-003-EN-N Published by the EU Institute for Security Studies and printed in France by Jouve. Graphic design by Metropolis, Lisbon. Maps: Léonie Schlosser; António Dias (Metropolis). Cover photograph: Kenyan army soldier Nicholas Munyanya. Credit: Ben Curtis/AP/SIPA CONTENTS Foreword 5 Antonio Missiroli I. Introduction: history and origins 9 II. The business of war: capacities and conflicts 15 III. The business of politics: coups and people 25 IV. Current and future challenges 37 V. Food for thought 41 Annexes 45 Tables 46 List of references 65 Abbreviations 69 Notes on the contributors 71 ISSReportNo.27 List of maps Figure 1: Peace missions in Africa 8 Figure 2: Independence of African States 11 Figure 3: Overview of countries and their armed forces 14 Figure 4: A history of external influences in Africa 17 Figure 5: Armed conflicts involving African armies 20 Figure 6: Global peace index 22 Figure -

Diversity of Plants Used to Treat Respiratory Diseases in Tubah

International Scholars Journals International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology ISSN: 2326-7267 Vol. 3 (11), pp. 001-008, November, 2012. Available online at www.internationalscholarsjournals.org © International Scholars Journals Author(s) retain the copyright of this article. Full Length Research Paper Diversity of plants used to treat respiratory diseases in Tubah, northwest region, Cameroon D. A. Focho1*, E. A. P. Nkeng2, B. A. Fonge3, A. N. Fongod3, C. N. Muh1, T. W. Ndam1 1 and A. Afegenui 1 Department of Plant Biology, University of Dschang. P. O. Box 67, Dschang, Cameroon. 2 Department of Chemistry, University of Dschang, P. O. Box 63, Dschang, Cameroon. 3 Department of Plant and Animal Sciences, University of Buea, Cameroon. Accepted 17 September, 2012 This study was conducted in Tubah subdivision, Northwest region, Cameroon, aiming at identifying plants used to treat respiratory diseases. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to interview members of the population including traditional healers, herbalists, herb sellers, and other villagers. The plant parts used as well as the modes of preparation and administration were recorded. Fifty four plant species belonging to 51 genera and 33 families were collected and identified by their vernacular and scientific names. The Asteraceae was the most represented family (6 species) followed by the Malvaceae (4 species). The families Asclepiadaceae, Musaceae and Polygonaceae were represented by one species each. The plant part most frequently used to treat respiratory diseases in the study was reported as the leaf. Of the 54 plants studied, 36 have been documented as medicinal plants in Cameroon’s pharmacopoeia. However, only nine of these have been reported to be used in the treatment of respiratory diseases. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

The Anglophone Cameroon Crisis: by Jon Lunn and Louisa Brooke-Holland April 2019 Update

BRIEFING PAPER Number 8331, 17 April 2019 The Anglophone Cameroon crisis: By Jon Lunn and Louisa April 2019 update Brooke-Holland Contents: 1. Overview 2. History and its legacies 3. 2015-17: main developments 4. 2018: main developments 5. Events during 2019 and future prospects 6. Response of Western governments and the UN www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary 2 The Anglophone Cameroon crisis: April 2019 update Contents Summary 3 1. History and its legacies 5 2. 2015-17: main developments 8 3. 2018: main developments 10 4. Events during 2019 and future prospects 12 5. Response of Western governments and the UN 13 Cover page image copyright: Image 5584098178_709d889580_o – Welcome signs to Santa, gateway to the anglophone Northwest Region, Cameroon, March 2011 by Joel Abroad – Flickr.com page. Licensed by Attribution-Non Commercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)/ image cropped. 3 Commons Library Briefing, 17 April 2019 Summary Relations between the two Anglophone regions of Cameroon and the country’s dominant Francophone elite have long been fraught. Over the past three years, tensions have escalated seriously and since October 2017 violent conflict has erupted between armed separatist groups and the security forces, with both sides being accused of committing human rights abuses. The tensions originate in a complex and contested decolonisation process in the late-1950s and early-1960s, in which Britain, as one of the colonial powers, was heavily involved. Federal arrangements were scrapped in 1972 by a Francophone- dominated central government. Many English-speaking Cameroonians have long complained that they are politically, economically and linguistically marginalised. -

Improving Prospects for a Peaceful Transition in Sudan

Improving Prospects for a Peaceful Transition in Sudan Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°143 Nairobi /Brussels, 14 January 2019 What’s new? Protests across Sudan flared up as the government cut a vital bread subsidy. Economic grievances are fuelling demands for political change, with protest- ers calling on President Omar al-Bashir, in power since 1989, to resign. Authorities have responded with violence, killing dozens and arresting many more. Why does it matter? In the past, President Bashir and his government have been able to ride out popular demonstrations. But these newest protests, demanding Bashir resign because of economic mismanagement and corruption, have spread to loyalist regions and coincide with rising discontent in his party. What should be done? Foreign governments influential in Khartoum should continue to publicly discourage violence against demonstrators, with Western pow- ers signalling that future aid and, in the U.S.’s case, sanctions relief are at stake. They should seek to improve prospects for a peaceful transition by creating incentives for Bashir to step down. I. Overview Protests engulfing Sudanese towns and cities have seen dozens killed in crackdowns by security forces and could turn bloodier still. Demonstrators express fury over sub- sidy cuts and call for President Omar al-Bashir to resign. Discontent within the ruling party, the depth of the economic crisis and the diverse makeup of protests suggest Bashir has less room to manoeuvre than before. He may survive, though likely by suppressing protests with levels of violence that would reverse his recent rapproche- ment with Western powers and deepen Sudan’s economic woes. -

Report of Fact-Finding Mission to Cameroon

Report of fact-finding mission to Cameroon Country Information and Policy Unit Immigration and Nationality Directorate Home Office United Kingdom 17 – 25 January 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Preface 1.1 2. Background 2.1 3. Opposition Political Parties / Separatist 3.1. Movements Social Democratic Front (SDF) 3.2 Southern Cameroons National Council (SCNC) 3.6 Ambazonian Restoration Movement (ARM) 3.16 Southern Cameroons Youth League (SCYL) 3.17 4. Human Rights Groups and their Activities 4.1 The National Commission for Human Rights and Freedoms 4.5 (NCHRF) Action by Christians for the Abolition of Torture (ACAT) 4.10 Action des Chrétiens pour l’Abolition de la Torture ………… Nouveaux Droits de l’Homme (NDH) 4.12 Human Rights Defence Group (HRDG) 4.16 Collectif National Contre l’Impunite (CNI) 4.20 5. Bepanda 9 5.1 6. Prison Conditions 6.1 Bamenda Central Prison 6.17 New Bell Prison, Douala 6.27 7. People in Authority 7.1 Security Forces and the Police 7.1 Operational Command 7.8 Government Officials / Public Servants 7.9 Human Rights Training 7.10 8. Freedom of Expression and the Media 8.1 Journalists 8.4 Television and Radio 8.10 9. Women’s Issues 9.1 Education and Development 9.3 Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) 9.9 Prostitution / Commercial Sex Workers 9.13 Forced Marriages 9.16 Domestic Violence 9.17 10. Children’s Rights 10.1 Health 10.3 Education 10.7 Child Protection 10.11 11. People Trafficking 11.1 12. Homosexuals 12.1 13. Tribes and Chiefdoms 13.1 14. -

Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon

sustainability Article Urban Expansion and the Dynamics of Farmers’ Livelihoods: Evidence from Bamenda, Cameroon Akhere Solange Gwan 1 and Jude Ndzifon Kimengsi 2,3,* 1 Department of Geography and Planning, The University of Bamenda, Bambili 00237, Cameroon; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Technische Universität Dresden, 01737 Tharandt, Germany 3 Department of Geography, The University of Bamenda, Bambili 00237, Cameroon * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 June 2020; Accepted: 14 July 2020; Published: 18 July 2020 Abstract: There is growing interest in the need to understand the link between urban expansion and farmers’ livelihoods in most parts of sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), including Cameroon. This paper undertakes a qualitative investigation of the effects of urban expansion on farmers’ livelihoods in Bamenda, a primate city in Cameroon. Taking into consideration two key areas—the Mankon–Bafut axis and the Nkwen Bambui axis—this study analyzes the trends and effects of urban expansion on farmers’ livelihoods with a view to identifying ways of making the process more beneficial to the farmers. Maps were used to determine the trend of urban expansion between 2000 and 2015. Twelve farmers drawn from the target sites were interviewed, while three focus group discussions were conducted. Thematic analysis was employed to analyze perceptions of the effects and coping strategies of farmers to urban expansion. Using the livelihoods approach, farmers’ livelihoods repertoires and portfolios were analyzed for the periods before and after urban expansion. Between 2000 and 2015, the surface area for farmlands in Bamenda II and Bamenda III reduced from 3540 ha to 2100 ha and 2943 ha to 1389 ha, respectively. -

Country Travel Risk Summaries

COUNTRY RISK SUMMARIES Powered by FocusPoint International, Inc. Report for Week Ending September 19, 2021 Latest Updates: Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, India, Israel, Mali, Mexico, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, Ukraine and Yemen. ▪ Afghanistan: On September 14, thousands held a protest in Kandahar during afternoon hours local time to denounce a Taliban decision to evict residents in Firqa area. No further details were immediately available. ▪ Burkina Faso: On September 13, at least four people were killed and several others ijured after suspected Islamist militants ambushed a gendarme patrol escorting mining workers between Sakoani and Matiacoali in Est Region. Several gendarmes were missing following the attack. ▪ Cameroon: On September 14, at least seven soldiers were killed in clashes with separatist fighters in kikaikelaki, Northwest region. Another two soldiers were killed in an ambush in Chounghi on September 11. ▪ India: On September 16, at least six people were killed, including one each in Kendrapara and Subarnapur districts, and around 20,522 others evacuated, while 7,500 houses were damaged across Odisha state over the last three days, due to floods triggered by heavy rainfall. Disaster teams were sent to Balasore, Bhadrak and Kendrapara districts. Further floods were expected along the Mahanadi River and its tributaries. ▪ Israel: On September 13, at least two people were injured after being stabbed near Jerusalem Central Bus Station during afternoon hours local time. No further details were immediately available, but the assailant was shot dead by security forces. ▪ Mali: On September 13, at least five government soldiers and three Islamist militants were killed in clashes near Manidje in Kolongo commune, Macina cercle, Segou region, during morning hours local time. -

“Investigating the Causes of Civil Wars in Sub-Saharan Africa” Case Study: the Central African Republic and South Sudan

al Science tic & li P o u P b f l i o c l A a f Journal of Political Sciences & Public n f r a u i r o s J ISSN: 2332-0761 Affairs Review Article “Investigating the Causes of Civil Wars in Sub-Saharan Africa” Case Study: The Central African Republic and South Sudan Agberndifor Evaristus Department Political Science and International Relations, Istanbul Aydin University, Istanbul, Turkey ABSTRACT Civil wars are not new and they predate the modern nation states. From the time when nations gathered in well- defined or near defined geographical locations, there has always been internal wrangling between the citizens and the state for reasons that might not be very different from place to place. However, the tensions have always mounted up such that people took to the streets first to protest and sometimes, the immaturity of the government to listen to the demands of the people radicalized them for bloodshed. This paper shall empirically examine the cause of civil wars in Sub-Saharan Africa having at the back of its thoughts that civil wars are most times associated to political, economic and ethnic incentives. This paper shall try in empirical terms using data from already established research to prove these points. Firstly, it shall explain its independent variables which apparently are some underlying causes of civil wars. Secondly, it shall consider the dense literature review of civil wars and shall look at some definitions, theories of civil wars and data presented on a series of countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Lastly, it shall isolate two countries that will make up its comparative analysis and the explanations of its dependent variable by which it shall seek to understand what caused the outbreaks of civil wars in those two countries. -

SIPRI Yearbook 2018: Armaments, Disarmament and International

armed conflicts and peace processes 83 VI. Armed conflict in sub-Saharan Africa ian davis, florian krampe and neil melvin In 2017 there were seven active armed conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa: in Mali, Nigeria, the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Repub- lic of the Congo (DRC), Ethiopia, Somalia and South Sudan.1 In addition, a number of other countries experienced post-war conflict and tension or were flashpoints for potential armed conflict, including Burundi, Cameroon, the Gambia, Kenya, Lesotho, Sudan and Zimbabwe. In Cameroon long-standing tensions within the mainly English-speaking provinces worsened in 2017 and turned violent in September, while the far north continued to be affected by the regional Islamist insurgency of Boko Haram (also known as Islamic State in West Africa).2 The symbolic declara- tion of independence by militant anglophone secessionist groups on 1 Octo- ber set the stage for further violence in Cameroon.3 The conflict is creating a growing refugee crisis, with at least 7500 people fleeing into Nigeria since 1 October. 4 In Kenya, following serious electoral violence, the year ended with major divisions and tensions between President Uhuru Kenyatta and the opposition leader, Raila Odinga.5 In Zimbabwe political tensions led to a military coup during November and the replacement of President Robert Mugabe, who has ruled the country since its independence in 1980, by his former vice-president, Emmerson Mnangagwa.6 Burundi, the Gambia, Lesotho and Sudan each hosted a multilateral peace operation in 2017.7 This section reviews developments in each of the seven active armed conflicts.