The Boyer Company, a Utah Corporation and H. Roger Boyer Dba the Boyer Compnay V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100 Years: a Century of Song 1970S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1970s Page 130 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1970 25 Or 6 To 4 Everything Is Beautiful Lady D’Arbanville Chicago Ray Stevens Cat Stevens Abraham, Martin And John Farewell Is A Lonely Sound Leavin’ On A Jet Plane Marvin Gaye Jimmy Ruffin Peter Paul & Mary Ain’t No Mountain Gimme Dat Ding Let It Be High Enough The Pipkins The Beatles Diana Ross Give Me Just A Let’s Work Together All I Have To Do Is Dream Little More Time Canned Heat Bobbie Gentry Chairmen Of The Board Lola & Glen Campbell Goodbye Sam Hello The Kinks All Kinds Of Everything Samantha Love Grows (Where Dana Cliff Richard My Rosemary Grows) All Right Now Groovin’ With Mr Bloe Edison Lighthouse Free Mr Bloe Love Is Life Back Home Honey Come Back Hot Chocolate England World Cup Squad Glen Campbell Love Like A Man Ball Of Confusion House Of The Rising Sun Ten Years After (That’s What The Frijid Pink Love Of The World Is Today) I Don’t Believe In If Anymore Common People The Temptations Roger Whittaker Nicky Thomas Band Of Gold I Hear You Knocking Make It With You Freda Payne Dave Edmunds Bread Big Yellow Taxi I Want You Back Mama Told Me Joni Mitchell The Jackson Five (Not To Come) Black Night Three Dog Night I’ll Say Forever My Love Deep Purple Jimmy Ruffin Me And My Life Bridge Over Troubled Water The Tremeloes In The Summertime Simon & Garfunkel Mungo Jerry Melting Pot Can’t Help Falling In Love Blue Mink Indian Reservation Andy Williams Don Fardon Montego Bay Close To You Bobby Bloom Instant Karma The Carpenters John Lennon & Yoko Ono With My -

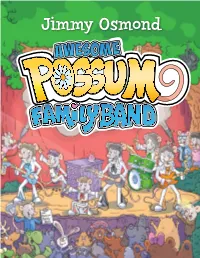

Jimmy Osmond Text Copyright © 2014 by Jimmy Osmond Illustrations Copyright © 2014 by Jimmy Osmond

Jimmy Osmond Text copyright © 2014 by Jimmy Osmond Illustrations copyright © 2014 by Jimmy Osmond All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, includ- ing photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, website, or broadcast. Cataloging-in-Publication data on file with the Library of Congress ISBN 978-1-62157-211-4 Published in the United States by Regnery Kids An imprint of Regnery Publishing, Inc. One Massachusetts Avenue NW Washington, DC 20001 www.Regnery.com Manufactured in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Books are available in quantity for promotional or premium use. Write to Director of Special Sales, Regnery Publishing, Inc., One Massachusetts Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20001, for information on discounts and terms, or call (202) 216-0600. Distributed to the trade by Perseus Distribution 250 West 57th Street New York, NY 10107 Dedication I wish to thank all those that helped me put this book together. Jeff Carneal, thank you for being a lifelong friend and believing in me for all of these years. A great big thank you to my friends Diane Lindsey Reeves and Cheryl Barnes for making this book happen for me. I have always loved to illustrate and cartoon and create characters, and wish to thank Bob Ostrom for not only being my art teacher and mentor, but for collaborating and helping to bring these characters and illustrations to life. -

Words+Images

MUSE IS THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL PUBLISHED BY THE LIT WORDS+IMAGES { FIRST ANNUAL MUSE L I T E R A R Y CO MPETITION } ISSUE02.09 VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 0 2 0 9 2contents UNREQUITED RELIGION GRANT BAILIE 6 GRANDPA RUDY ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON MARK KUHAR 7 PODIS JOHN PANZA 11 INFINITE LOSS ROB JACKSON 15 EIGHT TO FIVE, AGAINST (EXCERPT) MARY DORIA RUSSELL 18 BOXERS DON’T FLOSS AFTER EVERY BOUT JOHN DONOGHUE 20 BLUE GIRL MARK KUHAR 21 DANCING WITH SOMETHING SHIVA SAID 33rd cleveland international film festival CLAIRE MCMAHON BACKGROUND it’s starting march 19-29, 2009 tower city cinemas clevelandfilm.org LITTLE GIRL BLUE BILLY DELPS PLAYGROUND, NYC, 2003 JASON OASIS 26 A SENTIMENTAL JOURNEY AMY BRACKEN SPARKS VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 0 2 0 9 2contents UNREQUITED RELIGION GRANT BAILIE 6 GRANDPA RUDY ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON MARK KUHAR 7 PODIS JOHN PANZA 11 INFINITE LOSS ROB JACKSON 15 EIGHT TO FIVE, AGAINST (EXCERPT) MARY DORIA RUSSELL 18 BOXERS DON’T FLOSS AFTER EVERY BOUT JOHN DONOGHUE 20 BLUE GIRL MARK KUHAR 21 DANCING WITH SOMETHING SHIVA SAID 33rd cleveland international film festival CLAIRE MCMAHON BACKGROUND it’s starting march 19-29, 2009 tower city cinemas clevelandfilm.org LITTLE GIRL BLUE BILLY DELPS PLAYGROUND, NYC, 2003 JASON OASIS 26 A SENTIMENTAL JOURNEY AMY BRACKEN SPARKS Words + Images is our tag line, and for this issue, we focus on MUSE IS THE QUARTERLY JOURNAL PUBLISHED BY THE LIT Words as we publish the winners of the first annual MUSE VOLUME 2, ISSUE 1 Literary Competition. -

Osmonds El Eection D Fhb

RECORDS, redo MIRROR, OCTOBER 13, 1973 5 - I Rory - hits '.1a the Oxford (l0) and Fairfield. Croydon OW Ha world true takes in the States, S.'llserland, Spain. road B elgium. Holland and Japan Quo YES! Second OCTOBER 23 sees the start of a world tour for Rory Gallagher which Is Seekers billed as ending in Apra, sold 1974. TV dates Rory open. the British THE NEW SEEKERS, who Osmonds el eection d fhb. on November 111 with a concert al Cardiff+. are at present on coat -to- THERE will be another Osmond Road. London N4 as soon as Capitol Theatre. Mast concert lair of Amplerica Concert. It will be at London's possible. F tiler dales are Top wIN Lisa Mlnneh, return to out Rainbow Theatre on October 30.- Rank. Swansea (1a); Winter Ragland on Tuesday, October An Osmonds Fan Club Member- Garden., Bournemouth (211; 10. The group are aping í2.S0. [2.00 and Two Seats are priced at ship Card must be enclosed with the De Montfort Hall. Leicester guest appearance for The STATUS QUO have com- £1.00. Only one of people w'W (22): Derby Ronnie. BBC TV tarts and group application. Tickets will be drawn Kings Hall. (23); on pletely mid out their current be able to attend. These are Osmond Stadium, Uverpool (7.-251: aleo appear on It'. lulu UK tour. Both dates at on October 15. City Hall, Sheffield (2e); Free Saturday. November 3. The Fan Club members and they are group hope to spend the whole London's Rainbow have The Osmonds will now be flying Trade hall. -

MASTERS Podcast Club, December 2020 Marie Osmond Entertainer, Mother, Philanthropist & Warm, Wonderful Woman

MASTERS Podcast Club, December 2020 Marie Osmond Entertainer, Mother, Philanthropist & Warm, Wonderful Woman Marie Osmond has spent five decades as a singer, dancer, actor, author, television performer, and entrepreneur. Interviewed by Winn Claybaugh, this legendary celebrity and philanthropist discusses her five-decade career and how she has balanced worldwide fame with motherhood and giving back. While some celebrities only want to focus on their fame, Marie holds nothing back as she reveals her personal struggles with divorce, depression, losing a son to suicide, and more. This interview is mixed with tearful moments, lots of laughter, and powerful stories of overcoming, personal empowerment, and hope. Winn: Hi everyone, Winn Claybaugh here. During these uncertain times, there’s a lot of unknowns, fears, and anxiety in the world but there’s also a lot of stories of hope and inspiration. One story that really inspires me is a teenager named Colton, who is one of 10 million kids treated every year at Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals. Children’s hospitals are on the front lines of the pandemic and committed to serving their local communities. The reality is, kids can’t wait for a cure or for an economic boost. They need children’s hospitals now more than ever. I want to share Colton’s story with you as an example of the incredible work happening at local children’s hospitals. And if you’re inspired like I am, I invite you to support Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals and kids like Colton. [music plays] Announcer: In an effort to make sure no miracle is untold, Children’s Miracle Network Hospitals is honored to share Colton’s story. -

WJPA Power Line Survey Week of August 14, 1972 (Based on Listener

WJPA Power Line Survey Week of August 14, 1972 (based on listener requests and local and national sales ) THIS WEEK LAST WEEK 1.Don’t Mess Around With Jim – Jim Croce 7 2.Brandy – Looking Glass 5 3.Long Cool Woman – The Hollies 3 4.Alone Again Naturally – Gilbert O’Sullivan 2 5.Coconut – Nilsson 1 6.Motorcycle Mama – Sailcat 6 7.Black and White – Three Dog Night 9 8.Hold You Head Up – Argent 11 9.If Loving You Is Wrong – Luther Ingram 4 10.Baby Don’t Get Hooked on Me – Mac Davis 25 11.Goodbye To Love - The Carpenters 14 12.Rock and Roll Part II – Gary Glitter 20 13.Where Is The Love - Flack & Hathaway 13 14.I’m Still In Love With You – Al Green 16 15.Saturday in the Park - Chicago 26 16.Daddy Don’t You Walk So Fast – Wayne Newton 8 17.Baby Let Me Take You - The Detroit Emeralds 30 18.Honky Cat - Elton John 29 19.Too Late Too Turn Back – The Cornelius Brothers 12 20.Guitar Man – Bread 21 21.Happy - The Rolling Stones 23 22.Happiest Girl - Donna Fargo 33 23.Hold Her Tight - The Osmonds 10 24.How Do You Do? - Mouth & MacNeal 24 25.Popcorn - Hot Butter -- 26.Join Together - The Who 27 27.Everybody Plays the Fool – The Main Ingredient 36 28.Backstabbers – The O’Jays 39 29.Take It Easy - The Eagles 18 30.Lookin Through The Windows – The Jackson Five -- 31.Lean On Me - Bill Withers 17 32.Conquistador – Procol Harum 19 33.You’re Still A Young Man - Tower of Power 31 34.Small Beginnings - Flash 35 35.America - Yes 37 36.Go All The Way - The Raspberries -- 37.Easy Living - Uriah Heep 40 38.From the Beginning - Emerson Lake & Palmer -- 39.Run To Me - The Bee Gees -- 40.City Of New Orleans - Arlo Guthrie 38 . -

Merrill Osmond to Perform Clasic Rock Hits at Snow

Merrill Osmond To Perform Clasic Rock Hits At Snow October 20, 2008 Contact: Greg Dart Snow College School Relations 435-283-7154 EPHRAIM - Merrill Osmond, former lead singer of the music group The Osmonds, will be performing at Snow College Oct. 29. Osmond, 55, will be playing songs from his recent cover album “A Tribute to Classic Rock.” “It’s a thrill to be able to have an artist of this caliber coming to play for us at Snow College,” said Snow College spokesman Greg Dart. “I’m sure Osmond will put on a good show.” The fifth of nine children in his family, Osmond’s voice is credited for originally spurring the group to fame in the early 1970s. That’s not to say that pop is all he plays-he is now a solo touring artist and has released two rock- based cover albums. Classic rock is Osmond’s favorite musical genre-and perhaps his performing forte. At Snow, he will play several old favorites like “Takin’ Care of Business,” “Born To Be Wild” and “Don’t Want to Miss a Thing”-including “Hold Her Tight,” a popular Osmonds song he created as a young man that hit high in the charts both in America and internationally. A release by Osmond’s recording company claims that “his versatility as a solo singer is a best-kept secret.” “He is a soulful, throaty rock and roll lead singer with a charismatic stage presence,” the release continues. “A Tribute to Classic Rock” is his newest addition to an almost lifelong assortment of musical titles. -

Various Rock 27 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Rock 27 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Rock 27 Country: US Released: 1971 MP3 version RAR size: 1346 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1457 mb WMA version RAR size: 1810 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 349 Other Formats: MIDI MOD MP1 AIFF DMF XM VOX Tracklist 1-1 –Carole King Smakwater Jack 1-2 –Janis Joplin Get It While You Can 1-3 –Joan Baez The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down 1-4 –Bill Withers Aint No Sunshine 2-1 –The Who Won't Get Fooled Again 2-2 –Rare Earth I Just Wanna Celebrate 2-3 –Graham Nash Military Madness 2-4 –The Guess Who Rain Dance 3-1 –Carpenters Super Star 3-2 –Lee Michaels Do You Know What I Mean 3-3 –Donny Osmond Go Away Little Girl 3-4 –The Moody Blues Story In Your Eye's 4-1 –Paul McCartney Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey 4-2 –The Osmonds Yo Yo 4-3 –Hamilton, Joe Frank & Reynolds Anabella 4-4 –Stephen Stills Marriane Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Super Rock Hits Volume II Deeds Electronic 551 A Various 551 A US 1971 (LP, Comp) Company Related Music albums to Rock 27 by Various Crosby, Stills & Nash - Just A Song Before I Go / Dark Star Donny Osmond - Go Away Little Girl Joan Baez - Hits/Greatest & Others Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young - Five Way Street Donny Osmond Of The Osmonds - Sweet And Innocent Joan Baez - Le Meilleur de Joan Baez - Volume 2 Donny Osmond - To You With Love, Donny Donny Osmond - The Donny Osmond Album Janis Joplin - Rare Pearls Graham Nash - Military Madness Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young - Month Celebration Copy The Osmonds, Donny Osmond, Donny & Marie Osmond, Marie Osmond - Osmondmania!. -

Sabbat Envenom Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sabbat Envenom mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Envenom Country: US Released: 2004 Style: Black Metal, Heavy Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1719 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1205 mb WMA version RAR size: 1226 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 908 Other Formats: MMF APE ASF ADX MPC MP2 AHX Tracklist Hide Credits Bewitch 1 Written-By – Temis Osmond The Sixth Candle 2 Written-By – Gezol Satan Bless You 3 Written-By – Gezol Evil Nations 4 Written-By – Gezol Devil Worship 5 Written-By – Elizaveat Reek Of Cremation 6 Written-By – Elizaveat Deathtemptation 7 Written-By – Gezol King Of Hell 8 Written-By – Gezol Eviler 9 Written-By – Gezol Carcassvoice 10 Written-By – Gezol Dead March 11 Written-By – Gezol Reminiscent Bells 12 Written-By – Temis Osmond 13 Black Fire 14 Ghost In The Mirror Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – R.I.P. Records Pressed By – DiscUSA Credits Bass, Vocals – Gezol Drums – Zorugelion Guitar [Guest], Keyboards [Keyboards] – Temis Osmond Guitar, Artwork – Elizaveat Producer [Produced By] – Sabbat Recorded By, Mixed By, Engineer [Engineered By] – Mr. Wada* Notes Recorded at C.C. Work in 1990. American rerelease of the 1991 CD with two live tracks as bonus (tracks 13,14). 1991 Evil Records / 2004 R.I.P. Records (printed on artwork). © & ® 2004 RIP Records (printed on CD). Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 7 06567 90302 9 Mastering SID Code: IFPI L794 Mould SID Code: IFPI 2D1N Matrix / Runout: 11/8/04 ENVENOM 01 Other (CD Outer Ring): DiscUSA [logotype] Other (CD Outer Ring): IFPI 2D1C Other versions Category Artist -

Volume 121-Part 6

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA (iongrrssional Record th PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 94 CONGRESS FIRST SESSION VOLUME 121-PART 6 MARCH 14, 1975 TO MARCH 20, 1975 (PAGES 6675 TO 7920) / ~,J ,~_. UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON, 1975 6954: CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-SENATE March 17,1975 "r thought he might as well know who he I commend the Girl Scouts of America However, The Osmonds have never was going to kill so r told him 'r am Pearl for the fine efforts which they have made Mesta.' His whole manner changed. He re forgotten the place where they first membered me as the lady who had addressed in behalf of our great Nation. They have learned to sing-the church. Alan has homeless boys at a refugee camp earller. He made outlets available for our young said time and time again: became our protector and kept the others people which have withstood the test of The church 15 so much a part of our l1ves, from harming us." time. Rooted in traditional American it enhances everything we do. Although she probably did not have such values, the ideals of the Girl Scouts have incidents in mind, Mrs. Mesta was a woman developed millions of girls into leaders Despite their youth, The Osmonds known for her zest who once said: "r always and responsible citizens. have performed in hundreds of cities and have a good time wherever r go." The Girl Scouts help girls become hamlets in every section of America and Whether representing her country over young women with good moral standards most of the world. -

A History of the Astoria Cinema and Rainbow Theatre, Finsbury Park

FROM COLMAN TO COSTELLO A HISTORY OF THE ASTORIA CINEMA AND RAINBOW THEATRE, FINSBURY PARK The Finsbury Park Astoria, later renamed the Rainbow Theatre, began life as an ‘atmospheric’ cinema in 1930, bringing entertainment and luxury to a densely populated part of Islington, north London. The Astoria’s opening feature film was Condemned starring Ronald Colman, who was one of the era’s most popular screen idols. By the 1960s the Astoria had developed a dual role both as a picture house and as a music venue. The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Nat ‘King’ Cole, Sarah Vaughan, Frank Sinatra and Jimi Hendrix all played there. Its final picture show in September 1971 featured a double bill of Gorgo and the Boulting Brothers’ Twisted Nerve. However, the building was not to remain dark for long and, a little over six weeks later, at time when many cinema theatres throughout Britain were being converted to use as bingo halls or being demolished, the Astoria reinvented itself. In November 1971, and rebranded as the Rainbow Theatre, it was to become legendary as a rock music venue, attracting some of the biggest names in contemporary and popular music. The Who, Frank Zappa, Pink Floyd, David Bowie, Miles Davis, Rory Gallagher, Queen, Liza Minnelli, The Jacksons and Bob Marley all performed at the Rainbow. Notable acts from the decade’s burgeoning reggae, punk and new wave scenes also appeared on the theatre’s famous stage. Elvis Costello headlined the final concert at the Rainbow in December 1981. In spite of being designated Grade II-listed status for its architectural importance, the building’s future remained undecided for many years. -

Butcher Babies Theyre Coming to Take Me Away Free Download

Butcher babies theyre coming to take me away free download LINK TO DOWNLOAD Listen to They're Coming to Take Me Away by Butcher Babies #np on #SoundCloud. Create & stream a free custom radio station based on the song They're Coming to Take Me Away by Butcher Babies on iHeartRadio! Music, radio and podcasts, all free. Listen online or download . /1/23 · They're Coming to Take Me Away $ 3 Don't Give a Fuck $ 4 Crazy Horses $ 5 Pussy Whipped $ Reviews /5(66). Butcher Babies get in the Halloween spirit with this new music video for their cover of the Napoleon XIV track "They’re Coming To Take Me Away" as a tribute to their favorite Halloween movies. Lyrics for They're Coming To Take Me Away by Butcher Babies. ¿Recuerdas cuando te escapaste y me puse de rodillas y le pidió que no lo haga porque me g. Butcher Babies lyrics - 43 song lyrics sorted by album, including "Lilith", "Magnolia Blvd.", "The Mirror Never Lies". They're Coming To Take Me Away Don't Give A Fuck Crazy Horses Pussy Whipped album: "Take It Like A Man" () Monsters Ball Igniter. /6/23 · GetYourRockOut chatted to the Butcher Babies at Download Festival For more interviews, news and reviews, head over to renuzap.podarokideal.ru!Author: GetYourRockOut. They're Coming to Take Me Away, Ha-Haaa! is a novelty record written and performed by Jerry Samuels (billed as Napoleon XIV), and released on Warner Bros. renuzap.podarokideal.ru song became an instant success in the United States, peaking at No.