Art Museums in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendices 2011–12

Art GAllery of New South wAleS appendices 2011–12 Sponsorship 73 Philanthropy and bequests received 73 Art prizes, grants and scholarships 75 Gallery publications for sale 75 Visitor numbers 76 Exhibitions listing 77 Aged and disability access programs and services 78 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and services 79 Multicultural policies and services plan 80 Electronic service delivery 81 Overseas travel 82 Collection – purchases 83 Collection – gifts 85 Collection – loans 88 Staff, volunteers and interns 94 Staff publications, presentations and related activities 96 Customer service delivery 101 Compliance reporting 101 Image details and credits 102 masterpieces from the Musée Grants received SPONSORSHIP National Picasso, Paris During 2011–12 the following funding was received: UBS Contemporary galleries program partner entity Project $ amount VisAsia Council of the Art Sponsors Gallery of New South Wales Nelson Meers foundation Barry Pearce curator emeritus project 75,000 as at 30 June 2012 Asian exhibition program partner CAf America Conservation work The flood in 44,292 the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit ANZ Principal sponsor: Archibald, Japan foundation Contemporary Asia 2,273 wynne and Sulman Prizes 2012 President’s Council TOTAL 121,565 Avant Card Support sponsor: general Members of the President’s Council as at 30 June 2012 Bank of America Merill Lynch Conservation support for The flood Steven lowy AM, Westfield PHILANTHROPY AC; Kenneth r reed; Charles in the Darling 1890 by wC Piguenit Holdings, President & Denyse -

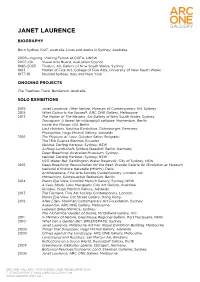

Janet Laurence

JANET LAURENCE BIOGRAPHY Born Sydney 1947, Australia. Lives and works in Sydney, Australia. 2008–ongoing Visiting Fellow at COFA, UNSW 2007–09 Visual Arts Board, Australian Council 1996–2005 Trustee, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney 1993 Master of Fine Art, College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales 1977–81 Studied Sydney, Italy and New York ONGOING PROJECTS The Treelines Track, Bundanon, Australia. SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 Janet Laurence: After Nature, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney 2018 What Colour is the Sacred?, ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne 2017 The Matter of The Masters, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney Transplant: A forest for chlorophyll collapse, Momentum, Berlin Inside the Flower, IGA Berlin Lost Habitats, Nautilus Exhibition, Oldenburger, Germany Phytophilia, Hugo Michell Gallery, Adelaide 2016 The Pleasure of Love, October Salon, Belgrade The 13th Cuenca Biennial, Ecuador Habitat, Darling Harbour, Sydney, NSW Auftrag Landschaft, Schloss Biesdorf, Berlin, Germany Deep Breathing, Australian Musueum, Sydney. Habitat, Darling Harbour, Sydney, NSW H2O Water Bar, Paddington Water Reservoir, City of Sydney, NSW 2015 Deep Breathing: Resuscitation for the Reef, Grande Galerie de l’Evolution at Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle (MNHN), Paris. Antrhopocene, Fine Arts Society Contemporary, London, UK Momentum, Kuntsquartier Bethanien, Berlin 2014 Plants Eye View, Dominik Mersch Gallery, Sydney, NSW. A Case Study, Lake Macquarie City Art Gallery, Austrlaia. Residue, Hugo Mitchell Gallery, Adelaide. 2013 The Ferment, Fine Art Society Contemporary, London. Plants Eye View, Cat Street Gallery, Hong Kong. 2012 After Eden, Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation, Sydney. Avalanche, ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne. Fabeled, BREENSPACE, Sydney. The Alchemical Garden of Desire, McClelland Gallery, VIC. -

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker

Gestural Abstraction in Australian Art 1947 – 1963: Repositioning the Work of Albert Tucker Volume One Carol Ann Gilchrist A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art History School of Humanities Faculty of Arts University of Adelaide South Australia October 2015 Thesis Declaration I certify that this work contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. In addition, I certify that no part of this work will, in the future, be used for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of the University of Adelaide and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. I give consent to this copy of my thesis, when deposited in the University Library, being made available for loan and photocopying, subject to the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. I also give permission for the digital version of my thesis to be made available on the web, via the University‟s digital research repository, the Library Search and also through web search engines, unless permission has been granted by the University to restrict access for a period of time. __________________________ __________________________ Abstract Gestural abstraction in the work of Australian painters was little understood and often ignored or misconstrued in the local Australian context during the tendency‟s international high point from 1947-1963. -

Annual Report Contents About Museums Australia Inc

Museums Australia (Victoria) Melbourne Museum Carlton Gardens, Carlton PO Box 385 Carlton South, Victoria 3053 (03) 8341 7344 Regional Freecall 1800 680 082 www.mavic.asn.au 08 annual report Contents About Museums Australia Inc. (Victoria) About Museums Australia Inc. (Victoria) .................................................................................................. 2 Mission Enabling museums and their Training and Professional Development President’s Report .................................................................................................................................... 3 services, including phone and print-based people to develop their capacity to inspire advice, referrals, workshops and seminars. Treasurer’s Report .................................................................................................................................... 4 Membership and Networking Executive Director’s Report ...................................................................................................................... 5 and engage their communities. to proactively and reactively identify initiatives for the benefit of existing and Management ............................................................................................................................................. 7 potential members and links with the wider museum sector. The weekly Training & Professional Development and Member Events ................................................................... 9 Statement of Purpose MA (Vic) represents -

2018-Annual-Report.Pdf

2018 ANNUAL REPORT GROWING TODAY. BUILDING New Fishermans Bend Campus 2022* Southbank Campus Redevelopment 2019* New Student Precinct 2022* THE IDEAS OF Engineering ideas for the 21st century Melbourne’s new creative centre Bringing the campus community together The University is creating a world-class engineering school for the This ambitious $200 million project, including the new Melbourne Co-created with students, the New Student Precinct at Parkville will 21st century, including a new purpose-built engineering campus Conservatorium, brings music and fine arts students together at the provide a place for students to connect, engage and innovate. TOMORROW at Melbourne’s Fishermans Bend – Australia’s newest design and heart of the Melbourne Arts Precinct. It supports the Faculty of Fine Arts This vibrant precinct will bring together student services with study engineering precinct. and Music’s standing as a world-leading arts education institution with spaces, arts and cultural facilities with food and retail outlets; all in close cutting-edge facilities and strong industry links. proximity to the Parkville campus. Science Gallery Melbourne 2020* Old Quadrangle Redevelopment 2019* Western Edge Biosciences Parkville 2019* Werribee Campus Redevelopment 2019* Growing minds in arts and science Reaffirming the heart of the University Where modern facilities meet our living Victoria’s world-class home for veterinary The newest addition to an acclaimed international network with eight Following an extensive restoration and the incorporation of cultural and heritage education and animal treatment nodes worldwide, the landmark Science Gallery Melbourne will be event spaces, the Old Quad will be reaffirmed as the University’s cultural, Bringing three faculties together for the first time, our Western Edge Through a $63 million investment, the University is expanding its embedded in the University of Melbourne ’s new innovation precinct, civic and ceremonial heart. -

News from the Collections

News from the collections Grainger Museum reopening Melbourne Conservatorium of The Grainger Museum officially Music; Dr Peter Tregear of Monash re-opened on Friday 15 October, University; and Brian Allison and following a seven-year closure. Astrid Krautschneider, Curators of Over the past few years substantial the Grainger Museum. conservation works were carried out The Grainger Museum is located on the heritage-registered building on Royal Parade, near Gate 13, under the supervision of conservation Parkville Campus. The opening architects Lovell Chen, along with hours are Tuesday to Friday 1pm to improvements to the facilities for 4.30pm and Sunday 1pm to 4.30pm. visitors, collections and staff. The new Closed Monday and Saturday, public suite of exhibitions, curated by the holidays and Christmas through Grainger Museum staff and designed January. Percy’s Café is open 8am to by Lucy Bannyan of Bannyan Wood 5pm, Monday to Friday. For further Design, explore Grainger’s life, times information or to join the mailing list and work. Funding was provided see www.grainger.unimelb.edu.au. by the University, the University Library, the University Annual MacPherson, Ormond Professor of G.W.L. Marshall-Hall: Appeal, bequests and donors. The Music and Director of the Melbourne A symposium guest speaker at the launch was Conservatorium of Music. Professor The collections of the Grainger Professor Malcolm Gillies, Vice- Gillies’ keynote paper ‘Grainger Museum provide an invaluable Chancellor of London Metropolitan 50 years on’ explored Percy Grainger’s research resource that extend far University and a leading Grainger current place in both the world of beyond the life and music of Percy scholar. -

Reading and Remembering Place Through Digital Photography: Exploration of an Ancient Site Diane Goodman University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2010 Reading and remembering place through digital photography: exploration of an ancient site Diane Goodman University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Goodman, Diane, Reading and remembering place through digital photography: exploration of an ancient site, Master of Arts thesis, University of Wollongong. School of Art and Design, University of Wollongong, 2010. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3174 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. Reading and Remembering Place through Digital Photography: Exploration of an Ancient Site A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Master of Arts Research from University of Wollongong by Diane Goodman School of Art & Design Faculty of Creative Arts 2010 VOLUME 1 Certification I, Diane Goodman, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Master of Arts, Research, in the School of Art & Design, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. This document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Diane Goodman May 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A very special thank you to Professor Diana Wood Conroy for her continuous supervision and support throughout this project. It would have been impossible to complete the project without her encouragement, compassion, humour and warmth, and above all, her belief in my ability to overcome the various personal obstacles I confronted along the way. -

Important Australian and Aboriginal

IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including The Hobbs Collection and The Croft Zemaitis Collection Wednesday 20 June 2018 Sydney INSIDE FRONT COVER IMPORTANT AUSTRALIAN AND ABORIGINAL ART including the Collection of the Late Michael Hobbs OAM the Collection of Bonita Croft and the Late Gene Zemaitis Wednesday 20 June 6:00pm NCJWA Hall, Sydney MELBOURNE VIEWING BIDS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION Tasma Terrace Online bidding will be available Merryn Schriever OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION 6 Parliament Place, for the auction. For further Director PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE East Melbourne VIC 3002 information please visit: +61 (0) 414 846 493 mob IS NO REFERENCE IN THIS www.bonhams.com [email protected] CATALOGUE TO THE PHYSICAL Friday 1 – Sunday 3 June CONDITION OF ANY LOT. 10am – 5pm All bidders are advised to Alex Clark INTENDING BIDDERS MUST read the important information Australian and International Art SATISFY THEMSELVES AS SYDNEY VIEWING on the following pages relating Specialist TO THE CONDITION OF ANY NCJWA Hall to bidding, payment, collection, +61 (0) 413 283 326 mob LOT AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 111 Queen Street and storage of any purchases. [email protected] 14 OF THE NOTICE TO Woollahra NSW 2025 BIDDERS CONTAINED AT THE IMPORTANT INFORMATION Francesca Cavazzini END OF THIS CATALOGUE. Friday 14 – Tuesday 19 June The United States Government Aboriginal and International Art 10am – 5pm has banned the import of ivory Art Specialist As a courtesy to intending into the USA. Lots containing +61 (0) 416 022 822 mob bidders, Bonhams will provide a SALE NUMBER ivory are indicated by the symbol francesca.cavazzini@bonhams. -

Dragon Tails 2017 Hopes, Dreams and Realities

5th Australasian conference on Chinese diaspora history & heritage Dragon Tails 2017 Hopes, Dreams and Realities Conference program Golden Dragon Museum Bendigo, Victoria, Australia 23-26 November 2017 0 Contents Conference program 4 Program - Timetable at a glance 4 Program in detail 5 Abstracts and speaker profiles 8 List of participants 25 Event Partner Conference Sponsors La Trobe Asia The Asia Institute La Trobe University The University of Melbourne www.latrobe.edu.au/asia arts.unimelb.edu.au/asiainstitute Conference Contacts For questions or problems during the conference, please see the Registration desk. You should also feel free to speak to the convenors. In case of emergencies, call Nadia Rhook 0409 807 516, Leigh McKinnon 0407 303 518, Paul Macgregor 0418 571 572 www.dragontails.org.au [email protected] Twitter: @dragontailsconf Hashtag #dtails17 Dragon Tails 2017 Hopes, Dreams and Realities 5th Australasian conference on Chinese diaspora history & heritage Golden Dragon Museum, Bendigo, Victoria, Australia 23-26 November 2017 Hopes and dreams have profoundly shaped the histories of Chinese people and their descendants in Australasia and abroad. This central theme of “Dragon Tails 2017: Hopes, Dreams and Realities” highlights not only the role of imagination in shaping the actions of Chinese-Australasians, but also the realities and challenges that Chinese-Australasians have historically encountered in pursuing their hopes and dreams. The Dragon Tails conferences promote research into the histories and heritage of Chinese people, their descendants and their associates, in Australasia (Australia and New Zealand). The conferences also encourage awareness of the connections of Chinese in Australasia with the histories of Chinese people, their descendants and their associates in other countries. -

Artists Statement for Me the Nature of Colour Is the Colour of Nature

David Aspden Born Bolton, England, arrived Australia 1950 1935 - 2005 COLLECTIONS Aspden is represented in National Gallery of Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Art Gallery of Western Australia, Museums and Galleries of the Northern Territory, National Gallery of Victoria, Art Gallery of South Australia, and other state galleries. His work is found in regional galleries including Bathurst, Newcastle, Wollongong, Gold Coast, Orange, Armidale, Ballarat, Benalla, Muswellbrook, Manly, Stanthorpe and Geelong. Aspden’s paintings are hung in New Parliament House, Canberra and the NSW State Parliament. His work is in the collections of Artbank, Heide, Tarrawarra Museum of Art, Macquarie University, National Bank of Australia, Macquarie Bank, St George Bank, The Australian Club, Festival Hall Adelaide, Allens Arthur Robinson, Clayton Utz, Melbourne Casino, Fairfax, News Limited, University of Western Australia, Monash University, Beljourno Group, Shell Company of Australia Limited, and numerous corporate and private collections. Individual Exhibitions 1965 Watters Gallery, Sydney 1966 Watters Gallery, Sydney - March and November 1967 Watters Gallery, Sydney Strines Gallery, Melbourne 1968 Farmers' Blaxland Gallery, Sydney Gallery A, Melbourne 1970 Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney 1971 Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney 1973 Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney 1974 Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney 1975 Solander Gallery, Canberra 1976 Monash University, Victoria Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney 1977 Rudy Komon Art Gallery, Sydney 1981 Rudy Komon Art Gallery, -

(NETS) Victoria Submission

LC EIC Inquiry into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism and events sectors pandemic on the tourism and events sectors and events pandemic on the tourism Inquiry the impact of COVID-19 into & NETS Submission Victoria PGAV Submission 115 Public PG Galleries V VictoriaAssociation A LC EIC Inquiry into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism and events sectors Submission 115 PGAV & NETS Victoria Submission - Inquiry into the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the tourism and events sectors for regional centres. In 2019, NETS Victoria toured Public Galleries eight exhibitions to 21 public galleries in Victoria, Association of Victoria (PGAV) supporting the work of 112 artists and 11 curators. Public gallery sector in Victoria & National Exhibitions Touring The public gallery sector in Victoria is Australia’s oldest – the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) was Support (NETS) Victoria established in 1861 and was the nation’s first public gallery. It was followed by the establishment of Submission galleries across regional Victoria – the Art Gallery of Ballarat in 1884, Warrnambool Art Gallery in 1886, Bendigo Art Gallery in 1887 and Geelong Gallery in The Secretary 1896. Economy and Infrastructure Committee Parliament House, Spring Street Today, the public gallery sector in Victoria is large EAST MELBOURNE VIC 3002 and diverse – it spans 35 metropolitan galleries, 3 outer metropolitan galleries and 19 regional 14 April 2021 galleries. It includes flagship organisations the NGV, ACMI and Arts Centre Melbourne, together with Dear Sir / Madam local government owned and operated galleries (32), independent galleries and arts spaces (15) and The Public Galleries Association of Victoria (PGAV) university art museums (6). -

Bibliography

SELECTED bibliOgraPhy “Komentó: Gendai bijutsu no dōkō ten” [Comment: “Sakkazō no gakai: Chikaku wa kyobō nanoka” “Kiki ni tatsu gendai bijutsu: henkaku no fūka Trends in contemporary art exhibitions]. Kyoto [The collapse of the artist portrait: Is perception a aratana nihirizumu no tōrai ga” [The crisis of Compiled by Mika Yoshitake National Museum of Art, 1969. delusion?]. Yomiuri Newspaper, Dec. 21, 1969. contemporary art: The erosion of change, the coming of a new nihilism]. Yomiuri Newspaper, “Happening no nai Happening” [A Happening “Soku no sekai” [The world as it is]. In Ba So Ji OPEN July 17, 1971. without a Happening]. Interia, no. 122 (May 1969): (Place-Phase-Time), edited by Sekine Nobuo. Tokyo: pp. 44–45. privately printed, 1970. “Obŭje sasang ŭi chŏngch’ewa kŭ haengbang” [The identity and place of objet ideology]. Hongik Misul “Sekai to kōzō: Taishō no gakai (gendai bijutsu “Ningen no kaitai” [Dismantling the human being]. (1972). ronkō)” [World and structure: Collapse of the object SD, no. 63 (Jan. 1970): pp. 83–87. (Theory on contemporary art)]. Design hihyō, no. 9 “Hyōgen ni okeru riaritī no yōsei” [The call for the Publication information has been provided to the greatest extent available. (June 1969): pp. 121–33. “Deai o motomete” (Tokushū: Hatsugen suru reality of expression]. Bijutsu techō 24, no. 351 shinjin tachi: Higeijutsu no chihei kara) [In search of (Jan. 1972): pp. 70–74. “Sonzai to mu o koete: Sekine Nobuo-ron” [Beyond encounter (Special issue: Voices of new artists: From being and nothingness: On Sekine Nobuo]. Sansai, the realm of nonart)]. Bijutsu techō, no.