Artforum: "Special Film Issue"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motion Picture Posters, 1924-1996 (Bulk 1952-1996)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187034n6 No online items Finding Aid for the Collection of Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Processed Arts Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Elizabeth Graney and Julie Graham. UCLA Library Special Collections Performing Arts Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: http://www2.library.ucla.edu/specialcollections/performingarts/index.cfm The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Collection of 200 1 Motion picture posters, 1924-1996 (bulk 1952-1996) Descriptive Summary Title: Motion picture posters, Date (inclusive): 1924-1996 Date (bulk): (bulk 1952-1996) Collection number: 200 Extent: 58 map folders Abstract: Motion picture posters have been used to publicize movies almost since the beginning of the film industry. The collection consists of primarily American film posters for films produced by various studios including Columbia Pictures, 20th Century Fox, MGM, Paramount, Universal, United Artists, and Warner Brothers, among others. Language: Finding aid is written in English. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Performing Arts Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Performing Arts Special Collections. -

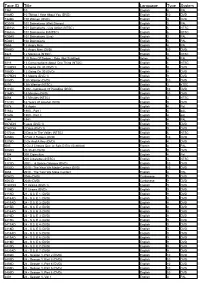

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Joel Stern Thesis

Joel Stern N5335612 KK51 Masters of Arts (Research) Creative Industries Faculty Thesis: Tracing the influence of non-narrative film and expanded cinema sound on experimental music. Supervisor – Dr. Julian Knowles ORDER OF CONTENTS Keywords: Expanded Cinema, Film Sound, Experimental Music, Audiovisual, Synchronisation, Michael Snow, Tony Conrad, Phill Niblock, Film Performance, Field Recording, Montage, Abject Leader. Table of Contents: 1. Purpose, Scope, Significance and Evaluation of the work (pp. 1-5) 2. The Filmmaker/Composer: New forms of synchronisation in the films of Michael Snow, Tony Conrad, Phill Niblock. (pp. 6-26) 3. Abject Leader: what makes these fields Shiver? Refracted forms of synchronisation in the films performances of Abject Leader (pp. 27-33) 4. Objects, Masks, Props: Hearing, capturing, assembling, disseminating sounds shaped by the aesthetic, conceptual and material influence of experimental film. (pp. 34-38) Creative works for submission: 1. Abject Leader ‘What Makes These Fields Shiver?’ DVD. A folio of audiovisual screen works and performance documentation made in collaboration with filmmaker Sally Golding. 2. Joel Stern ‘Objects, Masks, Props’ CD. A set of eight sonic compositions made by Joel Stern. “The work contained in this thesis has not been previously submitted to meet requirements for an award at this or any other higher education institution. To the best of my knowledge and belief, the thesis contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made.” Signature: Date: One Purpose, Scope, Significance and Evaluation of the work. The purpose of this study This study surveys and interrogates key conceptual frameworks and artistic practises that flow through the distinct but interconnected traditions of non- narrative film and experimental music, and examines how these are articulated in my own creative sound practise. -

UNIVERSITY of LONDON THESIS This Thesis Comes Within Category D

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year T o o ^ NameofAuthor •% C O P Y R IG H T This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962- 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

Anthology Film Archives 104

242. Sweet Potato PieCl 384. Jerusalem - Hadassah Hospital #2 243. Jakob Kohn on eaver-Leary 385. Jerusalem - Old Peoples Workshop, Golstein Village THE 244. After the Bar with Tony and Michael #1 386. Jerusalem - Damascus Gate & Old City 245. After the Bar with Tony and Michael #2 387. Jerusalem -Songs of the Yeshiva, Rabbi Frank 246. Chiropractor 388. Jerusalem -Tomb of Mary, Holy Sepulchre, Sations of Cross 247. Tosun Bayrak's Dinner and Wake 389. Jerusalem - Drive to Prison 248. Ellen's Apartment #1 390. Jerusalem - Briss 249. Ellen's Apartment #2 391 . European Video Resources 250. Ellen's Apartment #3 392. Jack Moore in Amsterdam 251, Tuli's Montreal Revolt 393. Tajiri in Baarlo, Holland ; Algol, Brussels VIDEOFIiEEX Brussels MEDIABUS " LANESVILLE TV 252. Asian Americans My Lai Demonstration 394. Video Chain, 253. CBS - Cleaver Tapes 395. NKTV Vision Hoppy 254. Rhinoceros and Bugs Bunny 396. 'Gay Liberation Front - London 255. Wall-Gazing 397. Putting in an Eeel Run & A Social Gathering 256. The Actress -Sandi Smith 398. Don't Throw Yer Cans in the Road Skip Blumberg 257. Tai Chi with George 399. Bart's Cowboy Show 258. Coke Recycling and Sheepshead Bay 400. Lanesville Overview #1 259. Miami Drive - Draft Counsel #1 401 . Freex-German TV - Valeska, Albert, Constanza Nancy Cain 260. Draft Counsel #2 402, Soup in Cup 261 . Late Nite Show - Mother #1 403. Lanesville TV - Easter Bunny David Cort 262. Mother #2 404. LanesvilleOverview #2 263. Lenneke and Alan Singing 405. Laser Games 264. LennekeandAlan intheShower 406. Coyote Chuck -WestbethMeeting -That's notRight Bart Friedman 265. -

Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1

* pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. These films shed light on the way Ger- many chose to remember its recent past. A body of twenty-five films is analysed. For insight into the understanding and reception of these films at the time, hundreds of film reviews, censorship re- ports and some popular history books are discussed. This is the first rigorous study of these hitherto unacknowledged war films. The chapters are ordered themati- cally: war documentaries, films on the causes of the war, the front life, the war at sea and the home front. Bernadette Kester is a researcher at the Institute of Military History (RNLA) in the Netherlands and teaches at the International School for Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Am- sterdam. She received her PhD in History FilmFilm FrontFront of Society at the Erasmus University of Rotterdam. She has regular publications on subjects concerning historical representation. WeimarWeimar Representations of the First World War ISBN 90-5356-597-3 -

Lycra, Legs, and Legitimacy: Performances of Feminine Power in Twentieth Century American Popular Culture

LYCRA, LEGS, AND LEGITIMACY: PERFORMANCES OF FEMININE POWER IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE Quincy Thomas A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Francisco Cabanillas, Graduate Faculty Representative Bradford Clark Lesa Lockford © 2018 Quincy Thomas All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor As a child, when I consumed fictional narratives that centered on strong female characters, all I noticed was the enviable power that they exhibited. From my point of view, every performance by a powerful character like Wonder Woman, Daisy Duke, or Princess Leia, served to highlight her drive, ability, and intellect in a wholly uncomplicated way. What I did not notice then was the often-problematic performances of female power that accompanied those narratives. As a performance studies and theatre scholar, with a decades’ old love of all things popular culture, I began to ponder the troubling question: Why are there so many popular narratives focused on female characters who are, on a surface level, portrayed as bastions of strength, that fall woefully short of being true representations of empowerment when subjected to close analysis? In an endeavor to answer this question, in this dissertation I examine what I contend are some of the paradoxical performances of female heroism, womanhood, and feminine aggression from the 1960s to the 1990s. To facilitate this investigation, I engage in close readings of several key aesthetic and cultural texts from these decades. While the Wonder Woman comic book universe serves as the centerpiece of this study, I also consider troublesome performances and representations of female power in the television shows Bewitched, I Dream of Jeannie, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, the film Grease, the stage musical Les Misérables, and the video game Tomb Raider. -

Reassessing the Personal Registers and Anti-Illusionist Imperatives of the New Formal Film of the 1960S and ’70S

Reassessing the Personal Registers and Anti-Illusionist Imperatives of the New Formal Film of the 1960s and ’70s JUAN CARLOS KASE for David E. James I think it would be most dangerous to regard “this new art” in a purely structural way. In my case, at least, the work is not, for example, a proof of an experiment with “structure” but “just occurs,” springs directly from my life patterns which unpre- dictably force me into . oh well . —Paul Sharits, letter to P. Adams Sitney1 In the dominant critical assessments of Anglo-American film history, scholars have agreed that much of the avant-garde cinema of the late 1960s and early ’70s exhibited a collective shift toward increased formalism. From P. Adams Sitney’s initial canonization of “Structural Film” in 19692 to Malcolm Le Grice’s “New Formal Tendency” (1972)3 and Annette Michelson’s “new cinematic discourse” of “epistemological concern” (1972)4 to Peter Gidal’s “Structuralist/Materialist Film” (1975)5—as well as in recent reconceptualizations and reaffirmations of this schol- arship by Paul Arthur (1978, 1979, and 2004), David James (1989), and A. L. Rees 1. Collection of Anthology Film Archives. Letter is dated “1969??.” Roughly fifteen years later, Sharits reiterated his frustration with the critical interpretations of his work in a more public context, albeit in slightly different terms: “There was a problem in the ’60s and even in the ’70s of intimidating artists into avoiding emotional motivations for their work, the dominant criticism then pursued everything in terms of impersonal, formal, structural analysis.” Jean- Claude Lebensztejen, “Interview with Paul Sharits” (June 1983), in Paul Sharits, ed. -

Blues Symphony in Atlanta Two Years Ago, Wynton Marsalis Embarked on a New Challenge: Fuse Classical Music with Jazz, Ragtime and Gospel

01_COVER.qxd 12/10/09 11:44 AM Page 1 DOWNBEAT DOWNBEAT BUDDY GUY BUDDY // ERIC BIBB // JOE HENRY JOE HENRY // MYRON WALDEN MYRON WALDEN DownBeat.com $4.99 02 FEBRUARY 2010 FEBRUARY 0 09281 01493 5 FEBRUARY 2010 U.K. £3.50 02-27_FRONT.qxd 12/15/09 1:50 PM Page 2 02-27_FRONT.qxd 12/15/09 1:50 PM Page 3 02-27_FRONT.qxd 12/15/09 1:50 PM Page 4 February 2010 VOLUME 77 – NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Contributing Designer Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 www.downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

GSC Films: S-Z

GSC Films: S-Z Saboteur 1942 Alfred Hitchcock 3.0 Robert Cummings, Patricia Lane as not so charismatic love interest, Otto Kruger as rather dull villain (although something of prefigure of James Mason’s very suave villain in ‘NNW’), Norman Lloyd who makes impression as rather melancholy saboteur, especially when he is hanging by his sleeve in Statue of Liberty sequence. One of lesser Hitchcock products, done on loan out from Selznick for Universal. Suffers from lackluster cast (Cummings does not have acting weight to make us care for his character or to make us believe that he is going to all that trouble to find the real saboteur), and an often inconsistent story line that provides opportunity for interesting set pieces – the circus freaks, the high society fund-raising dance; and of course the final famous Statue of Liberty sequence (vertigo impression with the two characters perched high on the finger of the statue, the suspense generated by the slow tearing of the sleeve seam, and the scary fall when the sleeve tears off – Lloyd rotating slowly and screaming as he recedes from Cummings’ view). Many scenes are obviously done on the cheap – anything with the trucks, the home of Kruger, riding a taxi through New York. Some of the scenes are very flat – the kindly blind hermit (riff on the hermit in ‘Frankenstein?’), Kruger’s affection for his grandchild around the swimming pool in his Highway 395 ranch home, the meeting with the bad guys in the Soda City scene next to Hoover Dam. The encounter with the circus freaks (Siamese twins who don’t get along, the bearded lady whose beard is in curlers, the militaristic midget who wants to turn the couple in, etc.) is amusing and piquant (perhaps the scene was written by Dorothy Parker?), but it doesn’t seem to relate to anything. -

History and Ambivalence in Hollis Frampton's Magellan*

History and Ambivalence in Hollis Frampton’s Magellan* MICHAEL ZRYD Magellan is the film project that consumed the last decade of Hollis Frampton’s career, yet it remains largely unexamined. Frampton once declared that “the whole history of art is no more than a massive footnote to the history of film,”1 and Magellan is a hugely ambitious attempt to construct that history. It is a metahistory of film and the art historical tradition, which incorporates multiple media (film, photography, painting, sculpture, animation, sound, video, spoken and written language) and anticipates developments in computer-generated new media.2 In part due to its scope and ambition, Frampton conceived of Magellan as a utopian art work in the tradition of Joyce, Pound, Tatlin, and Eisenstein, all artists, in Frampton’s words, “of the modernist persuasion.”3 And like many utopian modernist art works, it is unfinished and massive. (In its last draft, it was to span 36 hours of film.)4 By examining shifts in the project from 1971–80, as Frampton grapples with Magellan’s metahistorical aspiration, we observe substantial changes in his view of modernism. After an initial expansive phase in the early 1970s influenced by what he called “the legacy of the Lumières,” Frampton wrestles with ordering strategies that will be able to give “some sense of a coherence” to Magellan, finally develop- ing the Magellan Calendar between 1974–78, which provided a temporal map for each individual film in the cycle.5 But during 1978–80, an extraordinarily fertile *I am grateful to the following colleagues who supported the writing and revision of this essay: Kenneth Eisenstein, Tom Gunning, Annette Michelson, Keith Sanborn, Tess Takahashi, Bart Testa, and Malcolm Turvey. -

FLICKER Numérisation Des Films Argentiques : Impact Sur La Conservation Des Effets Visuels De Couleur Et De Papillotement

Projet FLICKER Numérisation des films argentiques : impact sur la conservation des effets visuels de couleur et de papillotement. Groupes Art contemporain et Apparence Couleur du Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France – C2RMF Cécile Dazord et Clotilde Boust http://obsolescence.hypotheses.org/ CINÉMA ARGENTIQUE ET « FLICKER » : LE CAS PARTICULIER DES FILMS DITS D’AVANT-GARDE OU EXPÉRIMENTAUX Fleur Chevalier, C2RMF 2011 PLAN CINÉMA ARGENTIQUE ET « FLICKER » : LE CAS PARTICULIER DES FILMS DITS D’AVANT-GARDE OU EXPÉRIMENTAUX......................................................................... 4 LE FLICKER : UNE NOTION À LA CROISÉE DE PLUSIEURS DISCIPLINES ............ 4 CINÉMA D’AVANT GARDE, CINÉMA EXPÉRIMENTAL : QUE RECOUVRE LE TERME « FLICKER » EMPLOYÉ DANS CE CONTEXTE ?............................................ 5 « FLICKER », « FLUTTER », « FLACKER », « STUTTER »,… CHAMPS LEXICAUX 6 I. JALONS HISTORIQUES ET THEORIQUES .................................................................. 6 1. P. Adams Sitney ............................................................................................................. 7 2. Malcolm Le Grice .......................................................................................................... 8 3. Film as film, formal experiment in film, 1910-1975.................................................... 11 4. Dominique Noguez ...................................................................................................... 14 5. William C. Wees .........................................................................................................