John Cage, Conceptualist Poet by Marjorie Perloff

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4' 33'': John Cage's Utopia of Music

STUDIA HUMANISTYCZNE AGH Tom 15/2 • 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.7494/human.2016.15.2.17 Michał Palmowski* Jagiellonian University in Krakow 4’ 33’’: JOHN CAGE’S UTOPIA OF MUSIC The present article examines the connection between Cage’s politics and aesthetics, demonstrating how his formal experiments are informed by his political and social views. In 4’33’’, which is probably the best il- lustration of Cage’s radical aesthetics, Cage wanted his listeners to appreciate the beauty of accidental noises, which, as he claims elsewhere, “had been dis-criminated against” (Cage 1961d: 109). His egalitarian stance is also refl ected in his views on the function of the listener. He wants to empower his listeners, thus blurring the distinction between the performer and the audience. In 4’33’’ the composer forbidding the performer to impose any sounds on the audience gives the audience the freedom to rediscover the natural music of the world. I am arguing that in his experiments Cage was motivated not by the desire for formal novelty but by the utopian desire to make the world a better place to live. He described his music as “an affi rmation of life – not an at- tempt to bring order out of chaos nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply a way of waking up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord” (Cage 1961b: 12). Keywords: John Cage, utopia, poethics, silence, noise The present article is a discussion of the ideas informing the radical aesthetics of John Cage’s musical compositions. -

PROGRAM NOTES My Entire Recital Takes Place Within the Context of a Cage Piece Consisting Only of Written Directions for Translating a Book Into Music

Fink 1 MATRICULAPHONY, a percussive circus on Van Meter Ames’ A BOOK OF CHANGES (title of composition) (adjective) (author) (title of book) PROGRAM NOTES My entire recital takes place within the context of a Cage piece consisting only of written directions for translating a book into music. The piece requires the creation of an original title followed by “circus on” and then the name of the book being used. As might be inferred from “circus,” the piece becomes a pandemonium of the book’s contents. In his directions, Cage calls for reducing the book’s words to a mesostic poem (think acrostic but with the spine down the middle. See example on page 4) and finding recordings of all sounds and from all places mentioned in the book. These sounds, after chance-determined manipulation, become the contents of an audio track that makes up the piece. Accordingly, my recital will be an hour of non-stop music and text, both live and pre-recorded. In the premiere of this piece, Cage used James Joyce’s novel, titling his piece “Roaratorio, an Irish Circus on Finnegan’s Wake.” In my realization, I am using an unpublished manuscript written by late UC philosophy professor Van Meter Ames, which I discovered while working at UC’s Archives and Rare Books Library. The manuscript details Ames’ friendship with Cage and consists largely of stories from Cage’s one year in residence at CCM in the 1966-67 academic year. Cage and Ames bonded over their shared interest in Zen philosophy and the aesthetics of art/music. -

Digging in John Cage's Garden; Cage and Ryōanji

Stephen Whittington, University of Adelaide Digging In John Cage’s Garden; Cage and Ryōanji1 To me a composer is like a gardener to whom a small portion of a large piece of ground has been allotted for cultivation; it falls to him to gather what grows on his soil, to arrange it, to make a bouquet of it, and if he is very ambitious, to develop it as a garden. It devolves on this gardener to collect and form that which is in reach of his eyes, his arms – his power of differentiation. In the same way a mighty one, an anointed one, a Bach, a Mozart, can only survey, manipulate and reveal a portion of the whole flora of the earth; a tiny fragment of that kingdom of blossoms which covers our planet, and of which an enormous surface, partly too distant, partly undiscovered, withdraws from the reach of the individual, even if he is a giant. And yet the comparison is weak and insufficient because the flora only covers the earth, while music, invisible and unheard, pervades and permeates a whole universe. (Ferruccio Busoni) 2 There is something very appealing about likening composition to gardening; both activities are part art, part science, and part manual labour. Busoni’s gardening analogy seems particularly appropriate for John Cage, who was a keen gardener himself; tending plants was part of his daily routine. My work is what I do and always involves writing materials, chairs, and tables. Before I get to it, I do some exercises for my back and I water the plants, of which I have around two hundred. -

': John Cage's Utopia of Music

STUDIA HUMANISTYCZNE AGH Tom 15/2 • 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.7494/human.2016.15.2.17 Michał Palmowski* Jagiellonian University in Krakow 4’ 33’’: JOHN CAGE’S UTOPIA OF MUSIC The present article examines the connection between Cage’s politics and aesthetics, demonstrating how his formal experiments are informed by his political and social views. In 4’33’’, which is probably the best il- lustration of Cage’s radical aesthetics, Cage wanted his listeners to appreciate the beauty of accidental noises, which, as he claims elsewhere, “had been dis-criminated against” (Cage 1961d: 109). His egalitarian stance is also refl ected in his views on the function of the listener. He wants to empower his listeners, thus blurring the distinction between the performer and the audience. In 4’33’’ the composer forbidding the performer to impose any sounds on the audience gives the audience the freedom to rediscover the natural music of the world. I am arguing that in his experiments Cage was motivated not by the desire for formal novelty but by the utopian desire to make the world a better place to live. He described his music as “an affi rmation of life – not an at- tempt to bring order out of chaos nor to suggest improvements in creation, but simply a way of waking up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord” (Cage 1961b: 12). Keywords: John Cage, utopia, poethics, silence, noise The present article is a discussion of the ideas informing the radical aesthetics of John Cage’s musical compositions. -

„Music – What For? “ John Cage's Musical Ideas for a Better World

Doris Kösterke „Music – what for? “ John Cage’s Musical Ideas for a Better World Lecture held during the Cairo Contemporary Music Days in collaboration with Department of Arts (AUC) on April 27th 2017 – 1:00 p.m. at Malak Gabr Arts Theatre American University New Cairo “For many years I have noticed, that music – as an activity separated from the rest of life – doesn’t enter my mind. Strictly musical questions are no longer serious questions” John Cage, 19761. „My ideas certainly started in the field of Music. And that field, so to speak, is child’s play. (We may have learned … in those idyllic days, things it behoves us now to recall.) Our proper work now if we love mankind and the world we live in is revolution”. John Cage, 19672 “… art is a sort of experimental station in which one tries out living“. John Cage, 19543 „Music – what for? “ 4 - Some answers by John Cage I think, it is a good idea to ask oneself “Why do I do what I am doing? “ - No matter whether you are an employee, an employer, a soldier, a teacher, or a musician. And - please, never be satisfied with the answer “for money”, Most composers don’t ask themselves. They take it for granted what music is made for. 1 John Cage: Empty Words. Writings `73-`78. Middletown, Conn. 1979 (JCE) p. 177. 2 Preface to A Year from Monday, John Cage: A Year from Monday. New Lectures and Writings. Middletown, Conn. 1967(JCA), p. IX; 16, cf. JCE, p. 182. 3 Lecture on Something, John Cage: Silence. -

John Cage and Van Meter Ames: Zen Buddhism, Friendship, and Cincinnati

John Cage and Van Meter Ames: Zen Buddhism, Friendship, and Cincinnati A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music by Serena Yang BFA, National Sun Yat-Sen University, 2011 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, PhD Abstract This thesis examines the previously undocumented friendship between John Cage and Van Meter Ames from 1957 to 1985 and Cage’s residency at the University of Cincinnati (UC) from January to May 1967. It considers Zen Buddhism as the framework of their friendship, and the residency as evidence of Cage’s implementation of his 1960s philosophy. Starting in 1957, Cage and Ames explored their common interest in Zen and social philosophies through extensive correspondence. This exchange added to the composer’s knowledge of Zen and Western philosophies, specifically pragmatism. Cage’s five-month tenure as composer-in-residence at UC enabled the two friends to be in close proximity and proved to be the highlight of their relationship. I suggest that this friendship and Ames’s publications contributed to Cage’s understanding of Zen during the 1960s and the development of his philosophy from this period. In the 1960s Cage’s spiritual belief diverged from his study of Zen with Daisetz T. Suzuki in the 1950s and was similar to Ames’s philosophic outlook. Cage and Ames both sought to bridge Western and Eastern cultures, assimilate Chinese philosophy, and modify Zen philosophy for modern society by adopting Thoreau’s humanistic and social theories, and relating pragmatism to their ideal social model. -

Merce Cunningham Dance Company the Legacy Tour

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS March 3–5, 2011 Zellerbach Hall Merce Cunningham Dance Company The Legacy Tour Dancers Brandon Collwes, Dylan Crossman, Julie Cunningham, Emma Desjardins, Jennifer Goggans, John Hinrichs, Daniel Madoff, Rashaun Mitchell, Marcie Munnerlyn, Krista Nelson, Silas Riener, Jamie Scott, Robert Swinston, Melissa Toogood, Andrea Weber Choreography Merce Cunningham (1919–2009) Founding Music Director John Cage (1912–1992) Music Director Takehisa Kosugi Director of Choreography Robert Swinston Executive Director Trevor Carlson Chief Financial Officer Lynn Wichern Director of Institutional Advancement Tambra Dillon Director of Production Davison Scandrett Company Manager Kevin Taylor Sound Engineer & Music Coordinator Jesse Stiles Lighting Director Christine Shallenberg Wardrobe Supervisor Anna Finke Production Assistant & Carpenter Pepper Fajans Archivist David Vaughan Music Committee David Behrman, John King, Takehisa Kosugi, Christian Wolff Lead support for the Cunningham Dance Foundation’s Legacy Plan, including the tour, has been provided by Leading for the Future Initiative, a program of the Nonprofit Finance Fund, funded by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; and an anonymous donor. These performances are made possible, in part, by Patron Sponsors Susan Marinoff and Thomas Schrag, Rockridge Market Hall, and the National Endowment for the Arts. Cal Performances’ 2010–2011 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 5 PROGRAM A PROGRAM A Thursday, March 3, 2011, 8pm First Performance Opéra National de Paris/Palais Garnier, Paris, Friday, March 4, 2011, 8pm January 13, 1998 Zellerbach Hall Restaged by Robert Swinston (2010). Merce Cunningham Dance Company The revival of Pond Way is a commission of Cal Performances. The revival and preservation of Pond Way are made possible, in part, through the generous support of American Express. -

John Cage: Zen Ox-Herding Pictures

*w \ Zen Ox-Herding Pictures Selected and Edited by Stephen Addiss & Ra> Kass M )HN CAGE: Zen Ox-Herd in a Pic together fifty never-before-seen T made in collaboration with renowned artist and composer John Cage, revealing the powerful influence of Zen in his life and work. These exquisite artifacts date from the 1988 Mountain Lake Workshop, where they were preparatory studies for greater endeavors by Cage. Now, nearly two decades later, these images have been utilized in a new collaboration as illustrations enlivening the classic "Ten Ox-Herding Pictures." The story of this collaboration draws upon resources from Cage's visual art, lectures, poetry, and the reflections of his colleagues and students. As try-out sheets for Cage's watercolor 9 paintings, each piece in this collection of paper towels was created serendipitously. And yet they are consistent in their visual exploration of the medium and appear as a cohesive group. Limited to c a small, subtle palette and a neutral ground, they or comprise a dynamic series in which no two images are alike, and where the possibilities of the medium are fully and enthusiastically revealed. Some images seem brittle, delicate, and on the verge of fading away; others are rich, dark, crossed by bold and energetic marks; and still others embrace both extremes, as though proposing a possible balance. Mountain Lake Workshop founder and director Ray Kass (who first recognized the beauty of these artifacts) and Stephen Addiss (scholar, artist, and student of Cage) provide introductory essays, discussing their own experiences with the collaboration. Juxtaposing Cage's meditative studies with the "Ten Ox-Herding Pictures," a series of images that has been used to communicate the essence of Zen for nearly one thousand years, the authors also explore fragments of Cage's poetry and his many statements about Zen practice. -

BRANCHES UDK 78.04.07Cage DOI: 10.4312/Mz.51.1.9-25

D. DAVIDOVIĆ • BRANCHES UDK 78.04.07Cage DOI: 10.4312/mz.51.1.9-25 Dalibor Davidović Akademija za glasbo, Univerza v Zagrebu Music Academy, University of Zagreb Branches Veje Prejeto: 17. januar 2015 Received: 17th January 2015 Sprejeto: 31. marec 2015 Accepted: 31st March 2015 Ključne besede: anarhija, programska glasba, im- Keywords: Anarchy, Program music, Improvisation, provizacija, poezija, znanje (v glasbi) Poetry, Knowledge (in music) IZVLEČEK ABSTRACT Članek, ki za svojo osnovo vzame pogovor med Joh- Taking the conversation between John Cage and nom Cageom in Geoffreyjem Barnardom – izdanim Geoffrey Barnard – published as Conversation kot Pogovor brez Feldmana (Conversation without without Feldman – as a starting point, the following Feldman) –, raziskuje Cageevo idejo anarhije. article explores Cage’s notion of anarchy. “Inwiefern ist die ratio eine Zwiesel?”1 Conversation without Feldman is a transcript of a conversation between two musi- cians. The older one, John Cage, was at that time already an artist with an international reputation, primarily as a composer but also as a writer and poet, and occasionally as a performer of his own pieces. Behind him were already some retrospectives, such as the famous 25-year Retrospective Concert that took place in 1958. Behind him was the famous appearance at the International Summer Course for New Music in Darmstadt in 1958, a shocking experience for many of his European colleagues. Behind him were the extrava- gant multimedia productions which took place during the late sixties and involved the participation of hundreds of performers and the use of the newest technologies. Behind him were already four collections of writings, not just lectures and articles dedicated to what he called experimental music, but also poetic cycles and the Diary series. -

THE STATE of RESEARCH on JOHN CAGE by Deborah Campana छ

HAPPY NEW EARS! IN CELEBRATION OF 100 YEARS: THE STATE OF RESEARCH ON JOHN CAGE By Deborah Campana छ In 1972, Don L. Roberts, while still rather new to his position as head of the Northwestern University Music Library, received a telephone call from someone who identified himself as John Cage. Roberts’s first in- stinct was doubt: was this a friend playing a prank? He chose to regard the call with all seriousness that was due. This was John Cage, and as a result, Northwestern’s Music Library became the home of a large portion of pri- mary source material that future generations may use to explore the com- plexities of the eminent composer/performer/poet/philosopher/artist. The seeds for this story, however, were actually planted a few decades earlier. IN THE BEGINNING To this point, Cage’s career developed swiftly and dramatically. Having grown up in Los Angeles for the most part, Cage’s west coast roots ex- tended into Seattle and San Francisco until the 1940s, when he and his wife Xenia moved briefly to Chicago and then to Manhattan in 1942. Compositions in these early years featured percussion instruments and other objects incorporated in music for small ensembles, or to accom- pany dance classes and performances. His New York debut occurred in 1943, where a concert including Amores (1943, prepared piano and per- cussion), Imaginary Landscape No.3 (1942, 6 percussion players), and works by others including Lou Harrison and Henry Cowell was pre- sented in association with the League of Composers at the Museum of Modern Art. -

John Cage's Living Theatre

From Martin Puchner and Alan Ackerman (eds.), Against Theatre: Creative Destruction on the Modernist Stage (New York: Palgrave, 2006), 133-48. John Cage’s Living Theatre Marjorie Perloff Where do we go from here? Towards theatre. That art more than music resembles nature. We have eyes as well as ears, and it is our business while we are alive to use them. --John Cage, “Experimental Music” (1957)1 When asked by David Shapiro whether he considered himself “as antitheatrical the way Jasper Johns is sometimes called antitheatrical,” John Cage responded emphatically: No. I love the theater. In fact, I used to think when we were so close together— Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, Christian Wolff, David Tudor, myself [in the early and mid-1950s]—I used to that that the thing that distinguished my work from theirs was that mine was theatrical. I didn’t think of Morty’s work as being theatrical. It seemed to me to be more, oh, you might say, lyrical. .And Christian’s work seemed to me more musical. whereas I seemed to be involved in theater. What could be more theatrical than the silent pieces—somebody comes on the stage and does absolutely nothing.2 Yet the same Cage repeatedly insisted that, when it came to the real theater, he could “count on one hand the plays I have seen that have truly interested me or involved me” (Conversing 105). As he explained it to Richard Kostelanetz: . when I bought a ticket, walked in, and saw this marvelous curtain go up with the possibility of something happening behind it, and then nothing happening . -

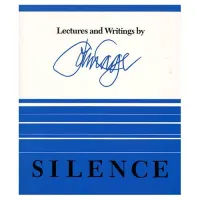

Silence: Lectures and Writings

SILENCE I I I Lectures and writings by JOHN CAGE WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS , ;'~ i I I WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS Published by University Press of New England Hanover, NH 03755 Copyright © 1939, 1944, 1949, 1952, 1955, 1957, 1958, 1959, 1961 by John Cage Ali rights reserved First printing, 1961. Wesleyan Paperback, 1973. Printed in the U rUted States of America 15 Paperback ISBN {}-8195-602~ Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 61-14238 Many of these lectures and articles were delivered or published elsewhere from 1939 to 1958. The headnute preceding each one makes grateful acknowledgment of its precise source. To Whom It May Concern Other Wesleyan University Pre•• books by Jobn Cage A Year from Monday: New Le<tUT'f!$ and Writings M: Writings '67-'72 Empty Words: Writings '73-'78 X: Writings '79-'82 MUSICAGE: CAGE MUSES an Words· Art· Music ',l I-VI " About the Author His teacher, Arnold Schoenberg, said John Cage was "not a composer but an inventor of genius." Composer, author, and philosopher, John Cage was born in Los Angeles in 1912 and by the age of 37 had been recognized by the American Academy of Arts and Letters for having extended the boundaries of music. He was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1978, and in 1982, the French government awarded Cage its highest honor for distinguished contribution to cultural life, Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres. Cage composed hundreds of musical works in his career, including the well known "4'33"" and his pieces for prepared piano: many of his compositions depend on chance procedures for their structure and perfonnance.