Lessons Learned from a Community Based Intervention to Improve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phdcfinalreport.Pdf

Disclaimer: “This document is an output from a project funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID)for the benefits of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID and AusAID”. 2 Table of Contents Disclaimer. ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Preamble ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Foreword.................................................................................................................................................. 8 Message .................................................................................................................................................. 9 Message ................................................................................................................................................ 10 Acknowledgements................................................................................................................................ 11 List of abbreviations ............................................................................................................................... 13 Executive summary................................................................................................................................ 14 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... -

Building Back Stronger

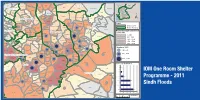

IOM One Room Shelters - 2011 Sindh Floods Response uc, manjhand odero lal village kamil hingoro jhando mari Punjab sekhat khirah Balochistan dasori San gha r ismail jo goth odero lal station khan khahi bilawal hingorjo Matiari roonjho khokhrapar matiari mirabad balouchabad tando soomro chhore bau khan pathan piyaro lund turk ali mari mirpurkhas-05 Sindh shaikh moosa daulatpur shadi pali tajpur pithoro shah mardan shah dhoro naro i m a khan samoon sabho kaplore jheluri Tando Allahpak singhar Yar mosu khatian ii iii iv missan tandojam dhingano bozdar hingorno khararo syed umerkot mirpur old haji sawan khan satriyoon Legend atta muhammad palli tando qaiser araro bhurgari began jarwar mir ghulam hussain Union Council bukera sharif tando hyder dengan sanjar chang mirwah Ume rkot District Boundary hoosri gharibabad samaro road dad khan jarwar girhore sharif seriHyd erabmoolan ad Houses Damaged & Destroyed tando fazal chambar-1 chambar-2 Mirpur Khas samaro kangoro khejrari - Flood 2011 mir imam bux talpur latifabad-20 haji hadi bux 1 - 500 kot ghulam muhammad bhurgari mir wali muhammad latifabad-22 shaikh bhirkio halepota faqir abdullah seri 501 - 1500 ghulam shah laghari padhrio unknown9 bustan manik laghari digri 1501 - 2500 khuda dad kunri 2501 - 3500 uc-iii town t.m. khan pabban tando saindad jawariasor saeedpur uc-i town t.m. khan malhan 3501 - 5000 tando ghulam alidumbalo shajro kantio uc-ii town t.m. khan phalkara kunri memon Number of ORS dilawar hussain mir khuda bux aahori sher khan chandio matli-1 thari soofan shah nabisar road saeed -

Government of Sindh Finance Department

2021-22 Finance Department Government of Sindh 1 SC12102(102) GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT/ HOUSE Rs Charged: ______________ Voted: 51,652,000 ______________ Total: 51,652,000 ______________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________ GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT ____________________________________________________________________________________________ BUILDINGS ____________________________________________________________________________________________ P./ADP DDO Functional-Cum-Object Classification & Budget NO. NO. Particular Of Scheme Estimates 2021 - 2022 ____________________________________________________________________________________________ Rs 01 GENERAL PUBLIC SERVICE 011 EXECUTIVE & LEGISLATIVE ORGANS, FINANCAL 0111 EXECUTIVE AND LEGISLATIVE ORGANS 011103 PROVINCIAL EXECUTIVE KQ5003 SECRETARY (GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT/ HOUSE) ADP No : 0733 KQ21221562 Constt. of Multi-storeyed Flats Phase-II at Sindh Governor's 51,652,000 House, Karachi (48 Nos.) including MT-s A12470 Others 51,652,000 _____________________________________________________________________________ Total Sub Sector BUILDINGS 51,652,000 _____________________________________________________________________________ TOTAL SECTOR GOVERNOR'S SECRETARIAT 51,652,000 _____________________________________________________________________________ 2 SC12104(104) SERVICES GENERAL ADMIN & COORDINATION Rs Charged: ______________ Voted: 1,432,976,000 ______________ Total: 1,432,976,000 ______________ _____________________________________________________________________________ -

Health Department District Sanghar & Tando Allahyar

Oversight Report Health Department District Sanghar & Tando Allahyar June 2014 This report was made possible with support from the American people through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents is the responsibility of Sustainable Development Foundation (SDF) and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of USAID or the U.S. Government. II Acknowledgements Sustainable Development Foundation (SDF)” is implementing Citizen’s Voice Project, in collaboration with USAID, under cycle 04, with thematic area “Citizens’ Voice and Accountability for Youth Development”. Main objective of the project is to aware youth about their health issues. We are very thankful of all members of Taluka and District Youth Councils in Sanghar and Tando Allahyar district, who are rendering their volunteer services to raise and advocate issues, related to youth at various levels for its resolution. We are grateful to CVP Team, for providing their continuous attention and kind feedback in finalization of this Report. We are also thankful of the health department officials of both districts who providing important data, which is a great support for us to understand the issues facing by the Youth. 1 List of Abbreviations SDF Sustainable Development Foundation CVP Citizen`s Voice Project USAID United State States Agency for International Development TYC Taluka Youth Council DYC District Youth Council BHU Basic Health Unit THQ Taluka Head Quarter DHQ District Head Quarter GD Government Dispensary 2 Table of Contents Title page……………………………………………………………………………………i Disclaimer………..…………………………………………………………………………ii Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………...…………iii List of Abbreviation………………………………………………………………………...iv Table of Contents...………………………………………………………………………...v Chapter 1: Introduction ......................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 1.1 Background .......................................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. -

Abbreviations and Acronyms

PART III] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JANUARY 24, 2019 123 ISLAMABAD, MONDAY, JANUARY 28, 2019 PART III Other Notifications, Orders, etc. ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 24th January, 2019 SUBJECT:— APPOINTMENT OF APPELLATE AUTHROTIES FOR CONDUCT OF BYE-ELECTIONS TO THE CATEGORY OF SEATS OF CHAIRMAN TC-PIYARO LUND, DISTRICT TANDO ALLAHYAR, CHAIRMAN & VICE-CHAIRMAN TC- DARYA KHAN MARI, DISTRICT NAUSHAHRO FEROZE AND CHAIRMAN TC-THERHI-II, DISTRICT KHAIRPUR IN SINDH PROVINCE. No. F. 6 (1)/2016-LGE(S).—In exercise of powers conferred upon it under Article 140 (A) of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan and in pursuance of the provision of sub-rule (5) of Rule 18 of Sindh Local Councils (Elections) Rule, 2015, the Election Commission of Pakistan has been pleased to appoint the following District & Sessions Judges as Appellate Authorities w.e.f (123) Price: Rs. 5.00 [113 (2019)/Ex. Gaz.] 124 THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JANUARY 28, 2019 [PART III 21-01-2019 for disposal of appeals against the decisions of the Returning Officers, accepting or rejecting the Nomination Papers filed by candidates for conduct of Local Government Bye-Elections to the category of seats OF CHAIRMAN TC-PIYARO LUND, DISTRICT TANDO ALLAHYAR, CHAIRMAN & VICE-CHAIRMAN TC-DARYA KHAN MARI, DISTRICT NAUSHAHRO FEROZE AND CHAIRMAN TC-THERHI-II, DISTRICT KHAIRPUR in Sindh province. Sr. Appellate Authority Jurisdiction No. 1 District & Sessions Judge, Tando Allahyar District Tando Allahyar District Naushahro 2 District & Sessions Judge, Naushahro Feroze Feroze 3 District & Sessions Judge, Khairpur District Khairpur By Order of the Election Commission of Pakistan. -

KARACHI RANGE 01 Sadar S/N Police Station Name Complete

KARACHI RANGE 01 Sadar S/N Police Station Name Complete Address of PS 01 Preedy Preedy Stret Temple road Karachi 02 City Court City Court near Karachi post office Tahir Saifuddin Road Karachi 03 Artillery Maidan Near Art Councial Pakistan near M.R.Kyani Road Karachi 04 Garden Heera Nund Khaim Sing Road Garden 05 Nabi Bux Heera Nand Cam Singh Road Karachi 06 Eidgah Inside Risala PS Nishtar road Karachi 07 Kharader Kharadar Police Station M.A.Jinnah Road Karachi 08 Mithadar M.A.Jinnah road Karachi 09 Risala Nishtar Road near Juna Market Karachi 10 City Court 02 Clifton S/N Police Station Name Complete Address of PS 11 Darakshan Plot No.1270 Street No.31 Khayaban Roomi Phase No.8 12 Gizri Plot No.P-38,11 Commercial Street Phase No.4 DHA Karachi Plot No.PS-1 Khyaban-e-Razwan Phase No.7 Ext DHA Main 13 Defence Korangi Road Karachi 14 Clifton Near Pak Tawar PTC Telephone Exchange Karachi Plot No.PS-1 Khyaban-e-Razwan Phase No.7 Ext DHA Main 15 Boat Basin Korangi Road Karachi 16 Frere Khaliq uz Zaman Road near Lully Bridge Karachi 03 Gulshan S/N Police Station Name Complete Address of PS 17 Gulshan-e-Igbal 18 Madina Main University Road Saforah Goth Chowrangi Kacchi Abadi 19 Sacahal Karachi 20 New 21 PIB Colony 22 Aziz Bhatti 23 Gulista-e-Jauhar 24 Bahadurabad 04 Kemari S/N Police Station Name Complete Address of PS 25 Jackson 26 KPT 27 Docks 28 Maripur 29 Sher Shah 30 DSP KESC 31 Women PS Gora Qabrastan Main Shahra-e-Faisal Karachi 32 N.A.B PS 33 SHO KESC 05 Liaquat Abad S/N Police Station Name Complete Address of PS 34 Liaquatabad Block 5 -

4 D °Ammo 06Dul Qudoos Gtvtemon)

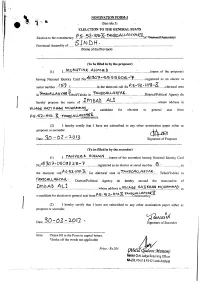

NOMINATION FORM-I (See rule 3) ELELCTION TO THE GENERAL SEATS 52- HYD-X- TANDOALIA YARTL, . Election to the constituency P5 • of , / srNN-4 Provincial Assembly of (Name of the Province) (To be filled in by the proposer) moKI-IT/AR, AHMED (1) (name of the proposer) having National Identity Card No 4130-1--• SS 5 5 606 .registered as an elector at serial number I 59 - in the electoral roll for P•S" 52 14-)1) electoral area inT4f(OOALLA1PeAt i.ehsil/Taluka in TA Al DOA tiA H /AR. • District/Political Agency do hereby propose the name of -I ri QAD whose address is • VILLAGE HAT1 k..torn) mc.)4AmmA9as candidate for election to general seat from AC .52- 14Y0 • E. • rANDOALLAWsktency•• (2) I hereby certify that I have not subscribed to any other nomination paper either as proposer or seconder. Date. 30 - o? - 2-013 Signature of Proposer (To be filled in by the seconder) (1) I TAN VEER 40SsA-IN (name of the seconder) having National Identity Card No 41307-05030 23-7 .registered as an elector at serial number a • in • the electoral roll P C - —S_ for electoral area in TA 1413°41-LA H YAK Tehsil/Taluka in TAND 0 ALLAJVPrk District/Political Agency. do hereby second the nomination • of Ilflb/41) 4-Lt whose address is ViLLA GcµA 31 KHAN N'101-tAftiniA0 • as TAN ti8AL LAW+ Y4127 a candidate for election to general seat from AS ' 6 a" 14 onstituency. (2) I hereby certify that I have not subscribed to .any other nomination paper either as proposer or seconder. -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Union Councils District Tando Allahyar Audit Year 2013-14 Auditor-General of Pakistan

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF UNION COUNCILS DISTRICT TANDO ALLAHYAR AUDIT YEAR 2013-14 AUDITOR-GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ..................................................................... i Preface ........................................................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................... iii SUMMARY TABLES AND CHARTS ...................................................................... vi Table 1: Audit Work Statistics....................................................................................... vi Table 2: Audit Observations .......................................................................................... vi Table 3: Outcome Statistics .......................................................................................... vii Table 4: Irregularities pointed out ............................................................................... viii CHAPTER-1 ................................................................................................................. 1 1. Union Councils, District Tando Allahyar ..........................................................1 1.1 Introduction .......................................................................................................1 1.2 AUDIT PARAS ............................................................................................... 3 1.2.1 Non-production of Record -

Of 266 CP-FORM 114 37111 13-10-2016 Trf

Hyderabad Electric Supply Company Date 13-10-2016 OUTSTANDING EQUIPMENT REMOVAL ORDER (GOVT) BILLING MONTH 09/2016 Page 1 of 266 Sub-Division 37111 HYD SADDAR CP-FORM 114 Amount Amount Amount Closing Ref. Fdr. Deferred Un-Paid Owing Balance S.No. Batch No. Trf Code Name And Address Order No & Date 1 04 0155300 03 062122 PRESS INFORMATION B.SHAH HYD 002012/06/040006 09/08/2012 - - 5181 174616 2 04 0157400 03 062122 D S P POLICE STATION A N FORCE B NO 54 A G O R CLY 200807/20/000001 01/10/2008 - - 1160 52228 HYD 3 04 0160000 03 062122 EXECUTIVE ENGINEER TEL CONST:DIVISION GSC (NTDC) 201503/04/000003 12/05/2015 - - 1951 17695 A-19 G.O.R COLONY HYD 4 04 0170600 03 062122 S.P./ANTI CORRUPTION G.NO.1 TY PE-E-V GOR*HYD 002014/01/040002 12/03/2014 848 - 22392 3927 5 04 0173200 03 006312 DISTRICT COORDINATION OFFICE CAMP OFFICE GOR COLONY 201411/04/000017 09/01/2015 214626 - 2265758 1531320 HYD 6 04 0176600 03 062122 A.D.C REST HOUSE HIGHWAY R.HOUSE THANDI SARAK HYD 201505/04/000011 09/07/2015 65070 - 521860 1405148 7 04 0523300 01 062105 CANT EXECUTIVE OFFICES H.NO.58 SADDAR HYD 199707/20/000017 12/09/1997 - - 525455 5343186 8 04 0552300 03 062103 CANTT:BOARD EYE HOSPITAL NEAR G.P.O HYD 201511/04/000011 11/01/2016 - - 11626 248133 9 06 0285400 03 062122 PAVALION RANI BAGH HYD 200609/20/000016 01/12/2006 - - 100256 7381830 10 06 0311100 01 062105 DIV.FOREST OFFICER THANDI SARAK HYD 201604/06/000007 13/06/2016 - - 98624 98832 11 06 0313600 03 062105 D.D ANTI CORRUPTION ESTB G.F SHAHBAZ BUILDING HYD 201602/06/000015 12/04/2016 42848 - 24915 100412 -

Audit Report on the Accounts of Chief Officer, District Council & Taluka Municipal Administrations District Tando Allahyar Audit Year 2012-13

AUDIT REPORT ON THE ACCOUNTS OF CHIEF OFFICER, DISTRICT COUNCIL & TALUKA MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATIONS DISTRICT TANDO ALLAHYAR AUDIT YEAR 2012-13 AUDITOR-GENERAL OF PAKISTAN TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... i Preface ................................................................................................................................ ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................. iii SUMMARY TABLES & CHARTS ............................................................................... vi Table 1: Audit Work Statistics ....................................................................................... vi Table 2: Audit observations Classified by Categories ................................................... vi Table 3: Outcome Statistics .......................................................................................... vii Table 4: Irregularities pointed out................................................................................ viii CHAPTER-1 ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 CHIEF OFFICER, DISTRICT COUNCIL AND TALUKA MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATIONS, TANDO ALLAHYAR ........................................... 1 1.1.1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 1 1.1.2 Comments on Budget and Accounts (Variance Analysis) -

Building Back Stronger

International Organization for Migration Photos: Usman Ghani, Manuel Pereira, IOM ORS team, Sajid Qayyum and Sher & Gul photographers Text: Helen Seeger, Ammarah Mubarak and Manuel Pereira Design: Amina Aaqib Printed at: Profile Printing Publishing Isb. The opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. © IOM 2014 All rights reserved Note: The names and identifying characteristics of beneficiaries referred to in this publication have been changed in line with IOM’s Data Protection Principles. FOREWORD he primary goal of the International Organization for akistan has faced significant destruction from Migration (IOM) is to facilitate the safe, orderly, humane monsoon flooding for three consecutive years. This Tand dignified management of migration. In many flooding has caused immense damage to already countries this includes supporting families and individuals P fragile lives, wiping out homes, livestock, personal that have been internally displaced by natural or man-made belongings and savings as families have struggled to disasters. In Pakistan, our work began with a response to the meet their basic needs during the displacement. Afghan refugee crisis, and has continued through the various challenges faced by the country since, including the 2005 In the context of declining levels of humanitarian and earthquake and flooding in 2010, 2011 and 2012. -

Election Commission of Pakistan Notification

ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN NOTIFICATION Islamabad, the 29th August, 2016 Subject:- RETURNED CANDIDATES AGAINST SEATS OF MAYOR/DEPUTY MAYOR AND CHAIRMEN / VICE CHAIRMEN IN RESPECT OF SINDH PROVINCE. No.F.9(10)/2015-LGE-(S).- In exercise of powers conferred upon it under Article 140 (A) of the Constitution of Islamic Republic of Pakistan and in pursuance of the provision of sub-section (1) of section 34 of the Sindh Local Government Act, 2013 , read with sub-rule (5) of Rule 42 of the Sindh Local Councils (Election) Rules 2015, and all other powers enabling it in that behalf, the Election Commission of Pakistan is pleased to notify hereunder, for information of general public, names of returned candidates against the following category of (ChairmanNice Chairman) in the local Council that are District Council, Muncipal Committee/Town Committees of District Tando Allahyar in the Local Government Elections, 2015 held on 24 August, 2016 in the Sindh Province. DISTRICT TANDO ALLAHYAR. NAME OF NAME OF FATHER'S / Sr. NAME OF CATEGORY PARTY LOCAL RETURNED HUSBAND's ADDRESS No DISTRICT OF SEATS AFFILIATION COUNCIL CANDIDATES NAME Makhdoom UC Missan Taluka Ali Muhammad Chairman Mian Lutuf Ali Jhando Mari, District NCIL Walhari AHYAR Walhari Tando Allahyar. 1 COU PPPP Village Mir CT Mir Muhammad Murad Vice Mir Behram TRI Muhammad Talpur, Taluka Chairman Khan Talpur TANDO ALL Ghulam DIS Jhando Mari, District Tando Allahyar. Syed Muhammad O Syed Wali Syed lmdad Hassan Shah, Deh ND Chairman Muhammad Hussain Shah Daro Suth, District TA Shah Tando Allahyar. E E 2 CIPAL PPPP S Manzil, Street No- UNI ALLAHYAR M Vice Muhammad 01, Chamber Naka, MMITT Jaffar Ali Khan Chairman Shahid District Tando TANDO CO Allahyar.