The Typhoid Fever Experience at Camp Thomas, 1898

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mind the Gaps: Investigating Collective Health Aggression

ACTA SCIENTIFIC MICROBIOLOGY (ISSN: 2581-3226) Volume 3 Issue 3 March 2020 Case Review Mind the Gaps: Investigating Collective Health Aggression Victor Lage de Araujo* Received: January 27, 2020 Laboratory Medicine, International Fellow, College of American Pathologist, MSC, Evidence-Based Healthcare (UCL), Brazil Published: February 05, 2020 © All rights are reserved by Victor Lage de *Corresponding Author: Victor Lage de Araújo, Laboratory Medicine, International Fellow, College of American Pathologist, MSC, Evidence-Based Healthcare (UCL), Araujo. Brazil. DOI: 10.31080/ASMI.2020.03.0505 Abstract localise its source – especially if it is an event hitting big numbers of patients, with high severity and quick development of symptoms Whenever one suspects some intoxication, infective epidemics or other collective health harm, it is paramount first to define and [23,24]. An outbreak investigation routine must be early established, with a comprising strategy and pragmatical objectives oriented towards precise diagnosis. Those will grant a realistic assessing of risks for the community, curative measures needed towards the ill and prevention directed to future cases. Healthcare professionals must have great attention towards novel aggressions to men's health and their clinical manifestations; a careful analysis of the available data is needed, in order to avoid being misled by some false assumption that may impair the accuracy of the diagnoses and might delay the needful curative and preventive courses directed towards the population [25]. The determinants of emerging diseases and unusual behaviour of the known microorganisms, health-aggressive mediums and artefacts are multiple; therefore, epidemiologists must consider every item of evidence for each upsurge, including the ecology and environmental issues [1,2]. -

Special Tohigh!

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SATURDAY. JULY. 2, 1904. 3 WOULD ISSUE DEATH DEPRIVES WORLD CABINET HOLDS DEMOCRATIC LEADERS MEET OF ART OF GREAT MASTER AND PREPARE FOR BATTLE WRIT TO MOYER At Age of Eighty-Seven George Frederick Watts, LAST MEETING English Painter, Lays Aside Brush That for Boom Is Launched for Platform Is Receiving the Plans .for the Organization Judge of Colorado Gathering Is Marked by Re- • Steele More Than Sixty Years Has Won Him Honors Folk of Missouri for the Serious Consideration of of the Convention Are Dissents From Decision tirement of Old and In- Presidency. the Delegates. Xot Complete. : Rendered in Miners' Case coming of New Officers ¦ His Candidacy Becomes En- Effort to Be Made to Have National Committee Will SCORES FELLOW JURISTS OATHS OF OFFICE TAKEN tangled With the Illi- It Meet Views of All Meet on Monday to Hear Says They Evaded 3Iain Secretaries Metcalf and Mor- nois Contest. Factions. Contests. Questions and Based Their ton Are Sworn In and CHICAGO, July 1.—Word was re- ST. LOUIS, July 1.—Longer In ad- ST. LOUIS. July 1.—Former Senator Opinion on False Theories Moody Takes Knox's Chair ceived from the East to-day which vance than usual the platform ques- James K. Jones, chairman of the Dem- launched in Illinois the boom of Joeaph tion Is receiving the serious considera- ocratic National Committee, arrfvetf la Demo- • — W. Folk of Missouri for the tion of delegates and others interested the city to-day and took apartments 'DENVER, July 1. Justice Robert Special Dispatch to The Call. -

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man

Issue Hero Villain Place Result Avengers Spotlight #26 Iron Man, Hawkeye Wizard, other villains Vault Breakout stopped, but some escape New Mutants #86 Rusty, Skids Vulture, Tinkerer, Nitro Albany Everyone Arrested Damage Control #1 John, Gene, Bart, (Cap) Wrecking Crew Vault Thunderball and Wrecker escape Avengers #311 Quasar, Peggy Carter, other Avengers employees Doombots Avengers Hydrobase Hydrobase destroyed Captain America #365 Captain America Namor (controlled by Controller) Statue of Liberty Namor defeated Fantastic Four #334 Fantastic Four Constrictor, Beetle, Shocker Baxter Building FF victorious Amazing Spider-Man #326 Spiderman Graviton Daily Bugle Graviton wins Spectacular Spiderman #159 Spiderman Trapster New York Trapster defeated, Spidey gets cosmic powers Wolverine #19 & 20 Wolverine, La Bandera Tiger Shark Tierra Verde Tiger Shark eaten by sharks Cloak & Dagger #9 Cloak, Dagger, Avengers Jester, Fenris, Rock, Hydro-man New York Villains defeated Web of Spiderman #59 Spiderman, Puma Titania Daily Bugle Titania defeated Power Pack #53 Power Pack Typhoid Mary NY apartment Typhoid kills PP's dad, but they save him. Incredible Hulk #363 Hulk Grey Gargoyle Las Vegas Grey Gargoyle defeated, but escapes Moon Knight #8-9 Moon Knight, Midnight, Punisher Flag Smasher, Ultimatum Brooklyn Ultimatum defeated, Flag Smasher killed Doctor Strange #11 Doctor Strange Hobgoblin, NY TV studio Hobgoblin defeated Doctor Strange #12 Doctor Strange, Clea Enchantress, Skurge Empire State Building Enchantress defeated Fantastic Four #335-336 Fantastic -

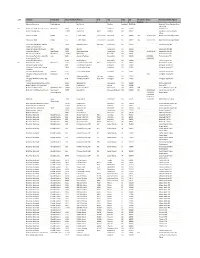

This Spreadsheet

2014 Location Association Street Number Address Unit City State Zip Associated Dates Associated Police Agency Campus Abertay University Study Abroad Bell Street Dundee Scotland DD1 1HG Scotland Police-Dundee Area Command NO Action in Comm Through Service WorkForce 3900 ACTS Lane Dumfries VA 22026 Dumfries PD Action Martial Arts 21690 Redrum Dr. #187 Ashburn VA 20147 Loudoun County Sheriff's Office Affinia 50 Hotel NSMH 155 E 50th Street 513,703,121 New York NY 10022 AN 11/07-11/09 New York Police Department Affinia 50 Hotel NSMH 155 E 50th Street 513,703,121 New York NY 10022 AN 11/14-11/16 New York Police Department Alexandria City Public Schools 1340 Braddock Place 7th Floor Alexandria VA 22314 Alexandria City PD Adult Learning Center Alexandria Detention Center CBO 2003 Mill Rd. Alexandria VA 22314 Alexandria City PD Alexandria Renew WorkForce 1500 Eisenhower Ave Alexandria VA 22314 11/20-12/18 Alexandria City PD American Iron Works WorkForce 13930 Willard Rd. Chantilly VA 20151 Fairfax County PD Americana Park Gerry Connelly Jaye 4130 Accotink Parkway Annandale VA 22003 4/3/2014 Fairfax County PD Cross Country Trail 6-18-2014 Annandale High School 4700 Medord Drive Annandale VA 22003 Fairfax County PD NO Annenberg Learner WorkForce 1301 Pennsylvania Ave NW #302 Washington DC 20004 Washington DC PD Arlington Career Center 816 South Walter Reed Dr. Arlington VA 22204 Arlington County PD Arlington County Fire Training 2800 South Tayler Street Arlington VA 22206 Arlington County PD Academy Arlington Dream Project Pathway 1325 S. Dinwiddie Street Arlington VA 22206 Arlington County PD Arlington Employment Center WorkKeys 2100 2014 Arlington County PD (WIB) Washington Blvd 1st Floor Arlington VA 22204 Arlington Mill Alternative High 816 S. -

A Review of Undulant Fever : Particularly As to Its Incidence, Origin and Source of Infection

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC MD Theses Special Collections 5-1-1938 A Review of undulant fever : particularly as to its incidence, origin and source of infection Richard M. Still University of Nebraska Medical Center This manuscript is historical in nature and may not reflect current medical research and practice. Search PubMed for current research. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses Part of the Medical Education Commons Recommended Citation Still, Richard M., "A Review of undulant fever : particularly as to its incidence, origin and source of infection" (1938). MD Theses. 706. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/mdtheses/706 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in MD Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ·~· A REVIEW OF UNDULANT FEVER PARTICULARLY AS TO ITS INCIDENCE, ORIGIN AND SOURCE OF INFECTION RICHARD M. STILL SENIOR THESIS PRESENTED TO THE COLLEGE OF MEDICINE, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA, OMAHA, NEBRASKA, 1958 SENIOR THESIS A REVIEW OF UNDULANT FEVER PARTICULARLY AS TO ITS;. INCIDENCE, ORIGIN .AND SOURCE OF INFECTION :trJ.:RODUCTION The motive for this paper is to review the observations, on Undul:ant Fever, of the various authors, as to the comps.rat!ve im- portance of' milk borne infection and infection by direct comtaC't.•.. The answer to this question should be :of some help in the diagnos- is ot Undulant Fever and it should also be of value where - question of the disease as an occupational entity is presented. -

The Ohio National Guard Before the Militia Act of 1903

THE OHIO NATIONAL GUARD BEFORE THE MILITIA ACT OF 1903 A thesis submitted To Kent State University in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Cyrus Moore August, 2015 © Copyright All rights reserved Except for previously published materials Thesis written by Cyrus Moore B.S., Ohio University, 2011 M.A., Kent State University, 2015 Approved by Kevin J. Adams, Professor, Ph.D., Department of History Master’s Advisor Kenneth J. Bindas, Professor, Ph.D, Chair, Department of History James L Blank, Ph.D., Dean, College of Arts and Sciences Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I. Republican Roots………………………………………………………19 II. A Vulnerable State……………………………………………………..35 III. Riots and Strikes………………………………………………………..64 IV. From Mobilization to Disillusionment………………………………….97 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………….125 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………..136 Introduction The Ohio Militia and National Guard before 1903 The second half of the nineteenth century witnessed a profound change in the militia in the United States. Driven by the rivalry between modern warfare and militia tradition, the role as well as the ideology of the militia institution fitfully progressed beyond its seventeenth century origins. Ohio’s militia, the third largest in the country at the time, strove to modernize while preserving its relevance. Like many states in the early republic, Ohio’s militia started out as a sporadic group of reluctant citizens with little military competency. The War of the Rebellion exposed the serious flaws in the militia system, but also demonstrated why armed citizen-soldiers were necessary to the defense of the state. After the war ended, the militia struggled, but developed into a capable military organization through state-imposed reform. -

Doane Robinson Collection Chronological Correspondence (1889-1946)

Doane Robinson Collection Chronological Correspondence (1889-1946) BOX 3359A Folder #1: Correspondence, 1889-1898 March 8, 1889 from W.T. La Follette. Seeking endorsement for his candidacy for U.S. Marshal. March 8, 1889 from Henry Neill. Seeking endorsement for Major D.W. Diggs as Territorial Treasurer. May 28,1891 to Wilfred Patterson. News release. July 16,1891 from Wm. H. Busbey. "Graphic Study in National Economy, "by Robinson. Feb.16,1892 from American Economist. "Graphic Study in National Economy." March 5, 1892 from U.S. Senator R.F. Pettigrew. "Graphic Study in National Economy." Feb. 25,1898 from N.G. Ordway. Capital fight of 1883. July 1, 1899 from C.H. Goddard. Goddard's poem "Grinnell." Folder #2: Correspondence, 1901 Jan. 22 from Pierre Chouteau. South Dakota State Historical Society. Feb. 2 from Pierre Chouteau. Honorary membership in South Dakota State Historical Society. Feb. 3 from Mrs. A.G. Sharp. Her capture by Indians in 1857 at Lake Okoboji. Feb. 4 from Nathaniel P. Langford. His book Vigilante Days and Ways. Feb. 5 from unknown past governor of Dakota. Relics. Feb. 5 from William Jayne. Experiences in Dakota. Feb. 9 from Mrs. William B. Sterling. Husband's effects. March 4 from Garrett Droppers, University of South Dakota. Life membership in Historical Society March 5 from T.M. Loomis. Offering books and papers. March 9 from Mrs. William B. Sterling. Husband's effects. March 22 from John A. Burbank. Razor fro museum. March 30 from Mrs. William B. Sterling. Husband's effects. July 17 from C.M. Young. First school house at Bon Homme. -

Terrible Typhoid Mary.” Much of What We Know About the Deadly Cook (CCSS ELA-LITERACY.RI 6-10.1-3; CCSS ELA-L.6-10.4-6; Comes from Other People

educator’s guide Terribleby Susan Typhoid Campbell Bartoletti Mary About the Author Susan Campbell Bartoletti is the award winning author of several books for young readers, includ- ing Black Potatoes: The Story of the Great Irish Famine, 1845–1850, winner of the Robert F. Sibert Medal. She lives in Moscow, Pennsylvania. Pre-Reading Activities Ask students to work in small groups and use print and online resources to define the following nine- teenth-century American terms: Industrial Revolution, Urbanization, First Wave of Immigration, Second Wave of Immigration, Tenement Housing, Infectious Disease, Sewage Systems, Germ Theory of Disease, and Personal Hygiene. (CCSS ELA-LITERACY.L.6-10.4-5) The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) are included with the discussions and activities. You can locate the standards at: www.corestandards.org/the- About the Book standards H “Energetic, even charming prose will easily engage Discussion Questions readers.” —School Library Journal, starred review CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.6-10.1 applies to each discussion question. H “Completely captivating.”—Booklist, starred review • Discuss the meaning of the similes, metaphors, H “Excellent nonfiction.” —Horn Book, starred review and allusions that comprise the book’s old-fash- With clarity, verve, and intelligence, Bartoletti presents ioned chapter titles both separately and in rela- the tale of “Typhoid Mary” Mallon, the Irish immigrant tionship to the body of the text. (CCSS ELA-LITERA- cook identified in the early 1900s as the first symptom- CY.L.6-10.5,6; CCSS ELA-LITERACY.RI.6-10.2,4) free carrier of an infectious disease. The author kicks off Mallon’s story with an outbreak of typhoid fever • Based on the information in the book’s early chap- in the Long Island home where she worked as a cook. -

Biographical Sketch of Dr. George M. Sternberg

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH OF DR. GEORGE M. STERNBERG. [Reprint from Physicians and Surgeons of America.] GEORGE M. STERNBERG. STERNBERG, George Miller, Washington, D. C., son of Rev. Levi (D. D.) and Mar- garet Levering (Miller) Sternberg, was born «r New York city, June 8, 1838. Educated at Hartwick Seminary, Otsego county, N. Y.; commenced the study of medicine in 1857, at Cooperstown, N. Y., under Dr. Horace Lathrop, of that place; attended two courses of lectures at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in the city of New York, and was graduated in iB6O. MILITARY AFFAIRS. Actual Rank. Assistant surgeon, May 28, 1861 ; accepted May 31, 1861 ; captain and assistant sur- geon, May 28, 1866; major and surgeon, Decem- ber 1, 1875; lieutenant-colonel and deputy sur- geon-general, January 12, 1891 ; brigadier-general and surgeon-general, May 30, 1893, retiring year, 1902 ; appointed from New York. Service. With General Sykes’s command, Army of the Potomac, to August, 1862; hospital duty, Portsmouth Grove, R. L, to November, 1862; with General Banks’s expedition, and assistant to the medical director, Department of the Gulf, to January, 1864; in office of medical director, Col- umbus, Ohio, and incharge of United States General at Hospital Cleveland, Ohio, to July, 1865 ; with the Thirteenth United States infantry, Jefferson Bar- racks, Mo., to April, 1866; post surgeon at Fort to Harker, Kan., October, 1867 (choleraepidemic) ; atFortRiley, Kan., and in the field from April, 1868, to 1870 (Indian campaign) ; Fort Columbus, New York harbor, to May, 1871 (yellow-fever epi- demic) ; Fort Hamilton, New York harbor, to June, 1871 ; Fort Warren, Boston harbor, Mass., to August, 1872; ordered to Department of the Gulf, July 22, 1872; acting medical director, New Orleans, La., to October, 1872; post surgeon, Fort Barrancas, Fla., to August, 1875 (epidemics of yellow fever in 1873 and 1875); on sick leave to May, 1876; ordered to Department of the Columbia, May 11, 1876; attending surgeon department headquarters, to September, 1876; post surgeon, Fort Walla Walla, W. -

Typhoid Article

Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jhmas/article-abstract/55/4/363/723583 by UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL FLORIDA user on 04 April 2019 April 04 on user FLORIDA CENTRAL OF UNIVERSITY by https://academic.oup.com/jhmas/article-abstract/55/4/363/723583 from Downloaded Fever and Reform: The Typhoid Epidemic in the Spanish-American War VINCENT J. CIRILLO j LTHOUGH hostilities lasted only four months, the Spanish-American War led to significant reforms in military medicine. A defining event of the war was the typhoid fever epidemic of July to November 1898, which exposed the culpability of line officers and brought home to the army the supreme impor- tance of sanitation. Typhoid fever was the major killer of American soldiers during the Spanish-American War, running rampant through the national encampments. Every regiment in the First, Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth and Seventh Army Corps developed typhoid fever. In all, 20,738 recruits contracted the disease (82 percent of all sick soldiers) and 1,590 died, yielding a mortality rate of 7.7 percent. Typhoid fever accounted for 87 percent of the total deaths from disease occurring in the assembly camps during the war (Table 1). The camps at home proved more deadly than the Cuban battlefields. TYPHOID FEVER Typhoid fever, one of the great scourges of nineteenth-century armies, had a long history, and by the start of the war with Spain its symptoms, lesions, and causes had been identified. In the early decades of the century typhoid was one of the many diseases believed to arise from miasmas, the foul airs generated by putrefying animal and vegetable matter. -

Vaccines Through Centuries: Major Cornerstones of Global Health

REVIEW published: 26 November 2015 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00269 Vaccines Through Centuries: Major Cornerstones of Global Health Inaya Hajj Hussein 1*, Nour Chams 2, Sana Chams 2, Skye El Sayegh 2, Reina Badran 2, Mohamad Raad 2, Alice Gerges-Geagea 3, Angelo Leone 4 and Abdo Jurjus 2,3 1 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, Rochester, MI, USA, 2 Department of Anatomy, Cell Biology and Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon, 3 Lebanese Health Society, Beirut, Lebanon, 4 Department of Experimental and Clinical Neurosciences, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy Multiple cornerstones have shaped the history of vaccines, which may contain live- attenuated viruses, inactivated organisms/viruses, inactivated toxins, or merely segments of the pathogen that could elicit an immune response. The story began with Hippocrates 400 B.C. with his description of mumps and diphtheria. No further discoveries were recorded until 1100 A.D. when the smallpox vaccine was described. During the eighteenth century, vaccines for cholera and yellow fever were reported and Edward Jenner, the father of vaccination and immunology, published his work on smallpox. The nineteenth century was a major landmark, with the “Germ Theory of disease” of Louis Pasteur, the discovery of the germ tubercle bacillus for tuberculosis by Robert Koch, and the Edited by: isolation of pneumococcus organism by George Miller Sternberg. Another landmark was Saleh AlGhamdi, the discovery of diphtheria toxin by Emile Roux and its serological treatment by Emil King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, Saudi Arabia Von Behring and Paul Ehrlih. -

Lonely Sentinel

Lonely Sentinel Fort Aubrey and the Defense of the Kansas Frontier, 1864-1866 Defending the Fort: Indians attack a U.S. Cavalry post in the 1870s (colour litho), Schreyvogel, Charles (1861-1912) / Private Collection / Peter Newark Military Pictures / Bridgeman Images Darren L. Ivey History 533: Lost Kansas Communities Chapman Center for Rural Studies Kansas State University Dr. M. J. Morgan Fall 2015 This study examines Fort Aubrey, a Civil War-era frontier post in Syracuse Township, Hamilton County, and the men who served there. The findings are based upon government and archival documents, newspaper and magazine articles, personal reminiscences, and numerous survey works written on the subjects of the United States Army and the American frontier. Map of Kansas featuring towns, forts, trails, and landmarks. SOURCE: Kansas Historical Society. Note: This 1939 map was created by George Allen Root and later reproduced by the Kansas Turnpike Authority. The original drawing was compiled by Root and delineated by W. M. Hutchinson using information provided by the Kansas Historical Society. Introduction By the summer of 1864, Americans had been killing each other on an epic scale for three years. As the country tore itself apart in a “great civil war,” momentous battles were being waged at Mansfield, Atlanta, Cold Harbor, and a host of other locations. These killing grounds would become etched in history for their tales of bravery and sacrifice, but, in the West, there were only sporadic clashes between Federal and Confederate forces. Encounters at Valverde in New Mexico Territory, Mine Creek in Linn County, Kansas, and Sabine Pass in Texas were the exception rather than the norm.