Stakeholder Involvement in Watershed Management: a Case Study of Sunday Creek

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ground Water Pollution Potential of Perry County, Ohio

GROUND WATER POLLUTION POTENTIAL OF PERRY COUNTY, OHIO BY PAUL SPAHR GROUND WATER POLLUTION POTENTIAL REPORT NO. 42 OHIO DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF WATER WATER RESOURCES SECTION JUNE, 1997 This publication was financed through a grant from Ohio Environmental Protection Agency under provisions of Section 319 of the Clean Water Act as amended in 1987. ABSTRACT A ground water pollution potential map of Perry County has been prepared using the DRASTIC mapping process. The DRASTIC system consists of two elements: the designation of mappable units, termed hydrogeologic settings, and the superposition of a relative rating system for pollution potential. Hydrogeologic settings incorporate hydrogeologic factors that control ground water movement and occurrence including the depth to water, net recharge, aquifer media, soil media, topography (slope), impact of the vadose zone media, and hydraulic conductivity of the aquifer. The relative ranking scheme uses a combination of weight and ratings to produce a numerical value called the pollution potential index that helps prioritize areas with respect to ground water contamination vulnerability. Hydrogeologic settings and the corresponding pollution potential indexes are displayed on maps. Seven hydrogeologic settings were identified in Perry County. Ground water pollution potential indices ranged from 68 to 140. Perry County lies within the Glaciated Central and the Nonglaciated Central hydrogeologic setting. The northern third of Perry County is overlain by varying thicknesses of glacial till. Buried valleys underlie many of the modern streams in northern and western Perry County. The buried valleys contain variable thicknesses of interbedded outwash sand and gravel, fine- grained glacial till and lacustrine deposits, and alluvium. -

Sunday Creek Valley Water District 15945 Second Street Millfield, Ohio 45761 1-(740)797-2566

Sunday Creek Valley Water District 15945 Second Street Millfield, Ohio 45761 1-(740)797-2566 2016 Drinking Water Consumer Report The Sunday Creek Valley Water District has prepared the following report to provide information to you, the consumer, on the quality of our drinking water. Included within this report is general health information, water quality test results, how to participate in decisions concerning your drinking water, and water system contacts. Sources of Contamination All sources of drinking water (both tap water and bottled water) include rivers, streams, ponds, reservoirs, springs and wells. As water travels over the surface of the land or through the ground, it dissolves naturally occurring minerals and in some cases, radioactive material and can pick up substances resulting from the presence of animals or from human activity. Contaminants that may be present in source water includes: (A) Microbial contaminants such as viruses and bacteria, which may come from sewage treatment plants, septic systems, agriculture livestock operations and wildlife; (B) Inorganic contaminants, such as salt and metals, which can be naturally occurring, or results from urban storm runoff, industrial or domestic waste water discharges, oil and gas production, mining, or farming: (C) Pesticides and Herbicides, which may come from a variety of sources such as agriculture, urban storm water runoff and residential uses: (D) Organic chemical contaminates, including synthetic and volatile organic chemicals, which are by products of industrial processes and petroleum production and can also come from gas stations: urban storm runoff and septic systems. (E) RadioaGtive contaminates, which can be naturally occurring or be the results of oil and gas production and mining activities. -

Influence of Water Quality and Sediment Transport on Biological Recovery Downstream of Lime Doser Systems a Thesis Presented To

Influence of Water Quality and Sediment Transport on Biological Recovery Downstream of Lime Doser Systems A thesis presented to the faculty of the Voinovich School of Leadership & Public Affairs In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Henry Bedu-Mensah August 2015 © 2015 Henry Bedu-Mensah. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Influence of Water Quality and Sediment Transport on Biological Recovery Downstream of Lime Doser Systems by HENRY BEDU-MENSAH has been approved for the Program of Environmental Studies and the Voinovich School of Leadership & Public Affairs by Natalie Kruse Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies Mark Weinberg Director, Voinovich School of Leadership & Public Affairs 3 ABSTRACT BEDU-MENSAH, HENRY, M.S., August 2015, Environmental Studies Influence of Water Quality and Sediment Transport on Biological Recovery Downstream of Lime Doser Systems Director of Thesis: Natalie Kruse Lime doser treatment for acid mine drainage (AMD) is often used in areas with insufficient space for passive treatment systems and in rural areas where more complex treatment systems would be impractical. In this study, assessment of pH, conductivity, sulfate, iron, manganese and aluminum was conducted for 8-11 miles downstream of each doser. Grain size profile and trace metal concentration in stream sediments were also analyzed. Doser downstream reaches’ field parameters, water quality profile and sediment were analyzed with R application and compared to assess differences in biological recovery in the four watersheds. Results of the study showed that precipitation of dissolved metals, high alkalinity content, high average grain size of sediment downstream of the doser treatment led to better biological improvement. -

Evaluation of the Impact from Two Point Sources of Acid

EVALUATION OF THE IMPACT FROM TWO POINT SOURCES OF ACID MINE DRAINAGE UPON FISH AND MACROINVERTEBRATE ASSEMBLAGES IN SUNDAY CREEK, OH A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Corey O. Kanuckel March 2003 This thesis entitled EVALUATION OF THE IMPACT FROM TWO POINT SOURCES OF ACID MINE DRAINAGE UPON FISH AND MACROINVERTEBRATE ASSEMBLAGES IN SUNDAY CREEK, OH By Corey O. Kanuckel has been approved for the Program of Environmental Studies and College of Arts and Sciences by Scott M. Moody Associate Professor of Biological Sciences Leslie A. Flemming Dean, College of Arts and Sciences KANUCKEL, COREY O. M.S. March 2003. Ecology Evaluation of the impact from two point sources of acid mine drainage upon fish and macroinvertebrate assemblages in Sunday Creek, OH. (99 pp.) Director of Thesis: Scott M. Moody The primary goal of this study was to quantify the effects from two point sources of acid mine drainage (AMD) upon the receiving biotic assemblages, specifically fish and macroinvertebrates, along the main branch of Sunday Creek, Southeastern OH. This study focused upon the response zone downstream from the Corning and Truetown point sources of AMD through the establishment of sample monitoring stations. These sample stations were analyzed to determine the extent of AMD disturbance over the spatial gradient of the stream. Selected biotic community parameters were compared to physiochemical parameters and sediment metals using a correlation matrix to determine which aspects of AMD appear most responsible for limiting these assemblages. -

SUNDAY CREEK WATERSHED Generated by Non-Point Source Monitoring System

2008 NPS REPORT SUNDAY CREEK WATERSHED Generated by Non-Point Source Monitoring System www.watersheddata.com • The Sunday Creek Watershed Group emerged from local residents’ concerns for the health of the Sunday Creek. Currently, we are a project of Rural Action. The Sunday Creek Watershed group office is located on 69 High St. Glouster Ohio 45732. The phone number is 740-767- 2225 and our web page is http://www.sunday- creek.org. Our most active partners are: Ohio Department of Natural Resources the divisions of Mineral Resource Management and Soil and Water Conservation; Ohio Environmental Pro- tection Agency; Office of Surface Mining; Ohio University; ILGARD; Hocking College; Trimble and Miller School District; Rural Action’s Envi- ronmental Learning Program and Sustainable Forestry; Local Village Councils; Local Township Trustees; Little Cities of Black Diamonds; Buck- eye Trail Group; Moose Lodge; Wayne National Forest; Burr Oak State Park. • Our mission statement, as adopted by the Sunday Creek Watershed Group in 2000; “The Sunday Creek Watershed Group is commit- ted to restoring and preserving water quality through community interaction, conservation, and education; in pursuit of a healthy ecosys- tem capable of supporting bio-diversity and recreation.” • The Sunday Creek Watershed is located in the Appalachian foothills, in the unglaciated part of Ohio. It is mostly rural with many small vil- lages throughout, and the majority of the land is privately owned. The Sunday creek watershed starts in the East Branch, north of Rendville and the West Branch at Shawnee. The creek follows SR 13 through Corning, Glouster, Millfield and it goes into the Hocking River right in Chaunc- ey. -

SUNDAY CREEK WATERSHED Generated by Non-Point Source Monitoring System

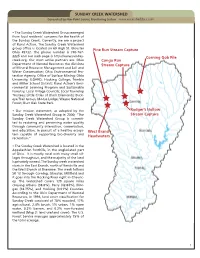

SUNDAY CREEK WATERSHED Generated by Non-Point Source Monitoring System www.watersheddata.com • The Sunday Creek Watershed Group emerged from local residents’ concerns for the health of the Sunday Creek. Currently, we are a project of Rural Action. The Sunday Creek Watershed group office is located on 69 High St. Glouster Pine Run Stream Capture Ohio 45732. The phone number is 740-767- 2225 and our web page is http://www.sunday- Corning Gob Pile creek.org. Our most active partners are: Ohio Congo Run Department of Natural Resources the divisions Stream Capture of Mineral Resource Management and Soil and Water Conservation; Ohio Environmental Pro- tection Agency; Office of Surface Mining; Ohio University; ILGARD; Hocking College; Trimble and Miller School District; Rural Action’s Envi- ronmental Learning Program and Sustainable Forestry; Local Village Councils; Local Township Trustees; Little Cities of Black Diamonds; Buck- eye Trail Group; Moose Lodge; Wayne National Forest; Burr Oak State Park. • Our mission statement, as adopted by the Rodger’s Hollow Sunday Creek Watershed Group in 2000; “The Stream Capture Sunday Creek Watershed Group is commit- ted to restoring and preserving water quality through community interaction, conservation, and education; in pursuit of a healthy ecosys- West Branch tem capable of supporting bio-diversity and Headwaters recreation.” • The Sunday Creek Watershed is located in the Appalachian foothills, in the unglaciated part of Ohio. It is mostly rural with many small vil- lages throughout, and the majority of the land is privately owned. The Sunday creek watershed starts in the East Branch, north of Rendville and the West Branch at Shawnee. -

Company Stores of the Hocking Valley Coal Field: Fading Memories from a Bygone Era

COMPANY STORES OF THE HOCKING VALLEY COAL FIELD: FADING MEMORIES FROM A BYGONE ERA Eugene J. Palka Department of Geography University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill li NTRODUCTION ponent of the "typical" coal mining community in Throughout the coal producing regions of Athens County, the state's leading coal producing Appalachia, one can identify and relate several county. I briefly recall the mining history of the classes of structures to specific eras in the settle study area, the role of the company store in newly ment history of the region. Mine buildings, tip established mining towns, and discuss various ples, company houses, and company stores are aspects of the store's form and function. I also the most readily identifiable classes of structures identify several of the relic structures which have that form a distinctive imprint on the cultural survived long after the decline of mining activities landscape, mainly because they are interrelated in the region, and continue to remind residents and uniformly date back to a specific time frame, and visitors of the region's coal mining heritage. and they occur in close juxtaposition (Palka, 1988a). The most celebrated of these coal mining THE STUDY AREA: HEART OF THE artifacts are the company stores. HOCKING VALLEY FIELD From the late nineteenth century through World War II, the company store was a common Although large-scale mining activities have feature of mining camps throughout the been abandoned for more than a half century, the Appalachian Coalfield. Significant not because of cultural imprint on Athens County, Ohio, remains its form, but because of its function, the stores clearly visible. -

No Change DATE: 05/28/2015 8:45 AM

ACTION: No Change DATE: 05/28/2015 8:45 AM 3745-1-08 Hocking river drainage basin. (A) The water bodies listed in table 8-1 of this rule are ordered from downstream to upstream. Tributaries of a water body are indented. The aquatic life habitat, water supply and recreation use designations are defined in rule 3745-1-07 of the Administrative Code. The state resource water use designation is defined in rule 3745-1-05 of the Administrative Code. The most stringent criteria associated with any one of the use designations assigned to a water body will apply to that water body. (B) Figure 1 of the appendix to this rule is a generalized map of Ohio outlining the water body drainage basins and listing associated rule numbers in Chapter 3745-1 of the Administrative Code. Figure 2 of the appendix to this rule is a generalized map of the Hocking river drainage basin. (C) RM, as used in this rule, stands for river mile and refers to the method used by the Ohio environmental protection agency to identify locations along a water body. Mileage is defined as the lineal distance from the downstream terminus (i.e., mouth) and moving in an upstream direction. (D) The following symbols are used throughout this rule: * Designated use based on the 1978 water quality standards; + Designated use based on the results of a biological field assessment performed by the Ohio environmental protection agency; o Designated use based on justification other than the results of a biological field assessment performed by the Ohio environmental protection agency; and L An L in the warmwater habitat column signifies that the water body segment is designated limited warmwater habitat. -

Southeastern Ohio and Adjacent Parts of West Virginia and Kentucky

Professional Paper No. 13 Series B, Descriptive Geology,.36 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SUKVEY CHARLES D. WALCOTT, DIRECTOR ' DRAINAGE MODIFICATIONS IN SOUTHEASTERN OHIO AND ADJACENT PARTS OF WEST VIRGINIA AND KENTUCKY BY "W. a. TIGHT WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1903 CONTENTS, Page. Introduction........................................................................... 7 Location of the area. .......................................................... 11 Present drainage and its relation to adjacent drainage.............................. 13 Through-flowing streams ........................................................ 13 Indigenous streams.................................................................... 13 Pre-Glacial drainage of adjacent regions .................................................... 17 General topographic features............................................................... 23 Characteristics of the present river valleys.................................................. 29 Through-flosving streams.............................................................. 29 Ohio Valley ...................................................................... 29 Muskingum Valley................................................................ 36 Hocking Valley................................................................... 35 Srioto Valley ...................................................................... 36 Summary ...................................................................... 38 Indigenous -

Sunday Creek Watershed

A Comprehensive Watershed Management Plan for the Sunday Creek Watershed Third Edition 2010 A Collaboration of the Partners of the Sunday Creek Watershed Group and the Residents of the Sunday Creek Watershed Revised by: Amber Leasure-Earnhardt Sunday Creek Watershed Coordinator Glouster, Ohio 69 High Street Glouster, Ohio 45732 740-767-2225 www.sundaycreek.org Sponsored by Rural Action, Inc. Table of Contents Section I: Watershed Overview Chapter I. Introduction Watershed Description..............................................................................................................................11 History of the Sunday Creek Valley In the Beginning ........................................................................................................................12 Boom and Bust Cycles of the Towns.......................................................................................13 Brief Histories of Four Towns within the Watershed......................................................13-15 Social and Cultural Resources .................................................................................................15 Demographics and Economic Infrastructure.........................................................................................16 Age and Sex Ratios ...................................................................................................................16 Economic Characteristics..........................................................................................................16 Occupations -

Up the Creek the Monday Creek Newsletter

A Publication of Rural Action UP THE CREEK THE MONDAY CREEK NEWSLETTER Monday Creek Restoration Project Volume 11 • Number 1 • Summer 2005 Tree planting on a Sunday Creek Coal Company reclamation site on April 24, 2004. Pictured are Boy Scouts from Troop 60 (Nelsonville), youth from New Straitsville, and Betsy Gosnell. Photo by Raina Ooten, 2004. Volunteering with Monday Creek by Betsy Gosnell Five years ago my husband and I “AMD and Art”. I didn’t know what mining, so I began attending meetings: moved to Southeast Ohio from Greater that was, but it sounded like fun and public meetings, where I met Office Cleveland so he could attend school at being new, I wanted to get involved. of Surface Mining (OSM) Interns Hocking College. We settled into the That was my first volunteer experience and Volunteers In Service To America small town of Murray City and the first with Monday Creek and from that mo- (VISTA); town council meetings where thing we noticed was the run-down ment on I was hooked! I met the Mayor, Volunteer Fire De- train depot across from our house. The I learned why the water was orange partment Chief, and staff from Ohio second thing we noticed was the orange and that AMD stood for acid mine Department of Natural Resources, creek running next to the depot. drainage, and that is what caused the Wayne National Forest and Environ- The following spring, I saw a sign water discoloration and prevented any mental Protection Agency. I learned in the Post Office for volunteers for an thing from living in it. -

Extent of Acid Mine Pollution in the United States Affecting Fish and Wildlife

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Stewart L. Udall, Secretary Frank P. Briggs, Assistant Secretary for Fish and Wildlife FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE Clarence F. Pautzke, Commissioner BUREAU OF SPORT FISHERIES AND WILDLIFE Daniel H. Janzen, Director EXTENT OF ACID MINE POLLUTION IN THE UNITED STATES AFFECTING FISH AND WILDLIFE By Edward C. Kinney, Staff Specialist Division of Fishery Management Services FISH AND WILDLIFE CIRCULAR 191 WASHINGTON JUNE 1964 CONTENTS Page Introduction ........................................ 1 Summary of results .................................. 2 Summaries of State reports Alabama ........................................ 4 Arkansas ........................................ 4 California ...................................... 4 Colorado ........................................ 5 Florida ........................................ 5 Illinois ........................................ 6 Indiana ........................................ 7 Iowa ............................................ 8 Kansas .......................................... 8 Kentucky ........................................ 8 Maine .......................................... 10 Maryland ........................................ 10 Minnesota ........................................ 10 Missouri ........................................ 11 Montana ........................................ 11 New Hampshire .................................... 12 Ohio ............................................ 12 Oklahoma 13 Pennsylvania ...................................