Organizational Legitimacy in the Field of International Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presidential Documents

Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents Monday, June 20, 2005 Volume 41—Number 24 Pages 981–1023 VerDate Aug 04 2004 10:14 Jun 21, 2005 Jkt 205250 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 1249 Sfmt 1249 E:\PRESDOCS\P24JNF4.017 P24JNF4 Contents Addresses and Remarks Communications to Congress See also Meetings With Foreign Leaders Budget amendments, letter transmitting—988 African Growth and Opportunity Act—983 Emergency Response Fund, letter on ‘‘An American Celebration at Ford’s reallocation—983 Theatre’’—983 Congressional picnic—1004, 1005 Communications to Federal Agencies Energy Efficiency Forum, 16th annual—999 Determination To Authorize a Drawdown for Medicare Modernization Act, implementing— Afghanistan, memorandum—1004 1006 Suspension of Limitations Under the Minnesota, discussion on implementing the Jerusalem Embassy Act, memorandum— Medicare Modernization Act in Maple 1004 Grove—1012 National Hispanic Prayer Breakfast—1005 Executive Orders Partnerships for Learning, Youth Exchange and Study, students—985 Amendment to Executive Order 13369, Pennsylvania, strengthening Social Security in Relating to the President’s Advisory Panel University Park—988 on Federal Tax Reform—1012 President’s Dinner—995 Implementing Amendments to Agreement on Radio address—982 Border Environment Cooperation Commission and North American Appointments and Nominations Development Bank—1020 Senate Confirmation of Thomas B. Griffith as a U.S. Appeals Court Judge for the District Letters and Messages of Columbia Circuit, statement—995 Juneteenth, message—1003 (Continued on the inside of the back cover.) Editor’s Note: The President was at Camp David, MD, on June 17, the closing date of this issue. Releases and announcements issued by the Office of the Press Secretary but not received in time for inclusion in this issue will be printed next week. -

Addressing World Hunger California Edison Division Vice President; Orange County Q & a with Gaddi Vasquez, U.S

SPECIAL REPORT ON AGING Special Report Gaddi At A Glance Age: 53 Main residence: Orange Family: Married to Elaine; son, Jason Career Highlights: Peace Corps director; Southern Addressing World Hunger California Edison division vice president; Orange County Q & A with Gaddi Vasquez, U.S. ambassador and former Peace Corps director Supervisor; chief deputy appointments secretary to former Gov. George Deukmejian; city of Orange police officer; various appointments to state boards and commissions by Deukmejian and former governors Pete Wilson and Gray Davis; and appointments to federal commissions by former By GAIL MATSUNAGA [email protected] a very personal level, I have a deep passion for the work that I President George H. W. Bush. am involved in now. The challenges can be daunting and over- ROM THE streets of Orange to ancient roads leading to whelming at times. But saving lives and giving hope to those in Hobbies: Reading, traveling, cycling F Rome, Gaddi Vasquez has seen many parts of the world need is work I believe in and have been committed to for more Philosophy on life: “Tests of life are sent to make us, not — most recently as the eighth U.S. representative to the United than 20 years.” to break us.” Nations Food and Agriculture Agencies in Rome. Role models: “George Deukmejian. I admire him because Vasquez returns to Orange County as the inaugural What is the biggest challenge for this country Gaddi Vasquez, right, feeds children in Honduras. he never lost sight of the trust that the people of California keynote speaker for Cal State Fullerton’s international confer- as it relates to world hunger? placed in him during his two terms as governor and other ence, “Connecting Worlds,” taking place April 17 and 18 as “The sheer magnitude of the hunger challenge is daunt- statewide constitutional offices. -

130556 IOP.Qxd

HARVARD UNIVERSITY John F. WINTER 2003 Kennedy School of Message from the Director INSTITUTE Government Spring 2003 Fellows Forum Renaming New Members of Congress OF POLITICS An Intern’s Story Laughter in the Forum: Jon Stewart on Politics and Comedy Welcome to the Institute of Politics at Harvard University D AN G LICKMAN, DIRECTOR The past semester here at the Institute brought lots of excitement—a glance at this newsletter will reveal some of the fine endeavors we’ve undertaken over the past months. But with a new year come new challenges. The November elections saw disturbingly low turnout among young voters, and our own Survey of Student Attitudes revealed widespread political disengagement in American youth. This semester, the Institute of Politics begins its new initiative to stop the cycle of mutual dis- engagement between young people and the world of politics. Young people feel that politicians don’t talk to them; and we don’t. Politicians know that young people don’t vote; and they don’t. The IOP’s new initiative will focus on three key areas: participation and engagement in the 2004 elections; revitalization of civic education in schools; and establishment of a national database of political internships. The students of the IOP are in the initial stages of research to determine the best next steps to implement this new initiative. We have experience To subscribe to the IOP’s registering college students to vote, we have had success mailing list: with our Civics Program, which sends Harvard students Send an email message to: [email protected] into community middle and elementary schools to teach In the body of the message, type: the importance of government and politics. -

Download File

SOWCmech2 12/9/99 5:29 PM Page 1 THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2000 e yne THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2000 The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) © The Library of Congress has catalogued this serial publication as follows: Any part of THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2000 The state of the world’s children 2000 may be freely reproduced with the appropriate acknowledgement. UNICEF, UNICEF House, 3 UN Plaza, New York, NY 10017, USA. ISBN 92-806-3532-8 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.unicef.org UNICEF, Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland Cover photo UNICEF/92-702/Lemoyne Back cover photo UNICEF/91-0906/Lemoyne THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S CHILDREN 2000 Carol Bellamy, Executive Director, United Nations Children’s Fund Contents Foreword by Kofi A. Annan, Secretary-General of the United Nations 4 The State of the World’s Children 2000 Reporting on the lives of children at the end of the 20th century, The State of the World’s Children 5 2000 calls on the international community to undertake the urgent actions that are necessary to realize the rights of every child, everywhere – without exception. An urgent call to leadership: This section of The State of the World’s Children 2000 appeals to 7 governments, agencies of the United Nations system, civil society, the private sector and children and families to come together in a new international coalition on behalf of children. It summarizes the progress made over the last decade in meeting the goals established at the 1990 World Summit for Children and in keeping faith with the ideals of the Convention on the Rights of the Child. -

Extensions of Remarks E431 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

March 1, 2007 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E431 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS RECOGNIZING JARRETT MUCK FOR most notable achievements of the IGY, the nexus of the Federal Government’s biosurveil- ACHIEVING THE RANK OF EAGLE discovery of belts of trapped, charged particles lance efforts. The NBIC will serve as a central- SCOUT in the Earth’s upper atmosphere by the late ized system for consolidating data from bio- Dr. James Van Allen of Iowa. logical surveillance systems and will be staffed HON. SAM GRAVES Yet the discovery of the Van Allen belts is by an interagency group of biosurveillance ex- OF MISSOURI just one of the significant scientific achieve- perts. Relevant data feeds will be brought to- ments of the IGY. Indeed, scientists around gether and analyzed to monitor any unusual IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES the world continue to build on the impressive health activity, including human, animal, agri- Thursday, March 1, 2007 research legacy left to them by their prede- cultural, food, and environmental health prob- Mr. GRAVES. Madam Speaker, I proudly cessors fifty years ago. Equally importantly, lems. This analysis will enable federal, State, pause to recognize Jarrett Muck, a very spe- the IGY has been a shining example of the and local governments, and private sector en- cial young man who has exemplified the finest benefits of international cooperation in sci- tities, to quickly detect and respond to a bio- qualities of citizenship and leadership by tak- entific endeavors. The coordination of global logical attack or an outbreak of any natural ing an active part in the Boy Scouts of Amer- interdisciplinary observations by researchers disease. -

Peace Corps Policy on Technology Usage for Volunteers

Peace Corps Times summer/fall 2006 Leaving One Foot at Home The artifact lays abandoned in a large one form of communication technology plastic box, a memory from the days of yore. over another. Once used regularly, Shan Shi no longer has Both Matthew and Shan just graduated need of it. The relic? A cellphone. from college, leading Shan to use more Shan, 23, and a Volunteer serving in economical means of communication. “My Turkmenistan, stowed away the techno- friends from home don’t call because they logical burden in favor of a more intimate are all recent graduates and poor like me,” form of communication: letters. “Especially she claims. However, with communication ones with stickers on the technology evolving, there front,” she adds. But Shan “Volunteers from the are more options than the presents just one side of sixties and seventies conventional phone call or the onslaught of new com- letter. munication technology just shake their heads Technology Volunteer preferences among Peace Lorena Hinojosa, 24, who Corps Volunteers looking and roll their eyes serves in Peru, has seen to stay in touch with family when we compare tremendous growth in and friends back home. the use of podcasting and Matthew Meyer, on the their communication blogging as new forms of other hand, is a fan of the experiences to mine.” communication. Both are cellphone. “Service in my unilaterally transmitted area is impeccable,” says the 23-year-old online: podcasts let Volunteers receive video Volunteer in Tanzania. To Matthew, phone information, such as news and sports clips, conversations are more personal because while blogs offer information for others to they provide an easier way to tell stories and view. -

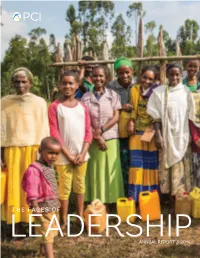

2014 Annual Report

THE FACES OF LEADERSHIP ANNUAL REPORT // 2014 At the heart of PCI is helping families and communities lift themselves out of poverty and create opportunities to build better lives for future generations. A RISE TO LEADERSHIP AMBASSADOR GADDI VASQUEZ From the migrant farms of Texas and California to In 2002, he was nominated by President George W. Bush, the halls of power in Washington and at the United and unanimously confirmed by the U.S. Senate, to serve Nations, Ambassador Gaddi Vasquez has lived the as the Director of the Peace Corps. During his tenure American dream and never forgotten the importance overseeing operations in 78 countries, the Peace Corps of giving back to others. Now he brings this quality of experienced a period of growth not seen in three decades leadership to his role as PCI’s Chairman of the Board. and greatly expanded its programs in the global fight against HIV/AIDS. Like the millions of individuals PCI impacts around the world every year, Vasquez had a childhood deeply In 2006, President Bush nominated him to serve as sowed in poverty, economic struggle, and hunger. He the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Agencies in learned early on from his parents that “to whom much Rome, Italy, acting as America’s leading voice in the fight is given, much is required,” and this philosophy shaped against poverty, hunger, and disease. His success as a his life in the public, corporate, and volunteer arenas. leader in combating hunger and malnutrition prompted the Director of the World Food Program to name Vasquez “My mother was determined to break the cycle of a “Champion Against World Hunger.” poverty by insisting that we advance our education If your actions inspire and achieve a better quality of life. -

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION INTERNATIONAL VOLUNTEERING LEADERSHIP FORUM BUILDING BRIDGES THROUGH INTERNATIONAL SERVICE Opening

THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION INTERNATIONAL VOLUNTEERING LEADERSHIP FORUM BUILDING BRIDGES THROUGH INTERNATIONAL SERVICE Opening Plenary 9:15 a.m. Washington, D.C. 2 SPEAKERS: DAVID CAPRARA Brookings Institution DAPHNE CASEY United Nations Volunteers DESIREE SAYLE USA Freedom Corps KIMBERLY PRIEBE World Teach Volunteer JEFF FLUG Millennium Promise RICHARD BLUM Blum Capital Partners, LP ANNE HAMILTON Peace Corps Volunteer ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 3 RONALD TSCHETTER United States Peace Corps Tuesday, December 5, 2006 P R O C E E D I N G S MR. CAPRARA: Good morning and welcome. Is everybody awake? My name is David Caprara. I’m director of the Brookings International Volunteering Project. We’re very happy you’ve come here. This feels like a reunion. We had a great kickoff in June to this project with Colin Powell, and a lot of work has been done since we came together. We’re now gathered here on the UN Volunteer Day to launch a very important coalition around international service called the Building Bridges Coalition. We have an exciting number of announcements and actions that will take place throughout the day. Assembled with us today are America’s leading NGOs and faith based international volunteering ANDERSON COURT REPORTING 706 Duke Street, Suite 100 Alexandria, VA 22314 Phone (703) 519-7180 Fax (703) 519-7190 4 organizations, the Peace Corps, government, the Administration and Congress, trendsetting corporations. We have a whole group of university leaders, faculty, students, administrators from around the region, and, most importantly, volunteers, fresh from their experiences on the front lines of service from abroad. -

Safety and Security of Peace Corps Volunteers Hearing

SAFETY AND SECURITY OF PEACE CORPS VOLUNTEERS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION MARCH 24, 2004 Serial No. 108–102 Printed for the use of the Committee on International Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.house.gov/international—relations U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 92–743PDF WASHINGTON : 2004 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 21 2002 10:27 Jul 13, 2004 Jkt 092188 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\FULL\032404\92743.000 HINTREL1 PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa TOM LANTOS, California DOUG BEREUTER, Nebraska HOWARD L. BERMAN, California CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York Vice Chairman ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American DAN BURTON, Indiana Samoa ELTON GALLEGLY, California DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey CASS BALLENGER, North Carolina SHERROD BROWN, Ohio DANA ROHRABACHER, California BRAD SHERMAN, California EDWARD R. ROYCE, California ROBERT WEXLER, Florida PETER T. KING, New York ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York STEVE CHABOT, Ohio WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts AMO HOUGHTON, New York GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York BARBARA LEE, California ROY BLUNT, Missouri JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado JOSEPH M. HOEFFEL, Pennsylvania RON PAUL, Texas EARL BLUMENAUER, Oregon NICK SMITH, Michigan SHELLEY BERKLEY, Nevada JOSEPH R. -

Independent Agencies and Government Corporations

INDEPENDENT AGENCIES AND GOVERNMENT CORPORATIONS ADVISORY COUNCIL ON HISTORIC PRESERVATION Type Level, Location Position Title Name of Incumbent of Pay Grade, or Tenure Expires Appt. Plan Pay Houston, TX ........... Chairman ........................................................... John L. Nau III .................. PA PD $100.00 4 Years 06/10/05 Albany, NY ............ Vice Chairman ................................................... Bernadette Castro .............. PA PD $100.00 4 Years 06/10/05 Nashville, TN ......... General Public Member .................................... Carolyn J. Brackett ............ PAS PD $100.00 4 Years Dallas, TX .............. ......do .................................................................. Emily R. Summers ............. PA PD $100.00 4 Years 06/10/06 Aurora, IL .............. Expert Member .................................................. Susan Snell Barnes ............ PA PD $100.00 4 Years 06/10/06 San Francisco, CA ......do .................................................................. Bruce D. Judd .................... PA PD $100.00 4 Years St. Marys City, MD ......do .................................................................. Julia A. King ...................... PA PD $100.00 4 Years 06/10/07 Denver, CO ............ ......do .................................................................. Ann Alexander Pritzlaff .... PA PD $100.00 4 Years 06/10/07 St. Paul, MN .......... Governor ............................................................. Timothy Pawlenty ............. -

Winter/Spring

IFYEIFYE NEWSNEWS The Official Publication of the International Four-H Youth Exchange Association of the USA Winter-Spring 2008 Les Brown - NJ IFYE to India 1956 Internationalist Warren E. Schmidt “Influential Thinker” and “Guru” 3 June 1917 - 20 November 2007 Lester R. Brown, a 4-H and IFYE alum, is founder and president of the Warren Schmidt (center-right) with seven IFYE alumni who joined the Earth Policy Institute. He has authored 50 books and received numerous Peace Corps in 1962 as Volunteers to Brazil in the first 4-H Peace Corps awards and 25 honorary degrees. The Washington Post called him “one of the project. He loved working with 4-H International participants. He worked world’s most influential thinkers.” The Telegraph of Calcutta refers to him with Extension, IFYE and 4-H Peace Corps, before taking an assignment as “the guru of the environmental movement.” (See page 4) at the UN/FAO headquarters in Rome. (See pages 4, 5, and 7) World IFYE Conference The Aussies and the Kangaroos Welcome You! Australia bound in October? The Australian Rural Exchangees Association and the Kangaroos - left and right - look forward to welcoming 4-H International exchange alumni and friends for the Ninth World IFYE Conference, 4-11 Octo- ber 2008 - registrations are still being accepted. Conference program and registration information is available on the website - www.ifyeoz2008.com - or e-mail [email protected] There are Pre/Post Conference Tours - the Petrak Tours and the Deisher Tours - organized by U.S. alumni. Space is still available. Contact Ron and Ruth Anne Petrak (515/262-3691 or [email protected]) and Art and Beth Deisher ([email protected] or 937/599-2559). -

New President Vows to Take LULAC to Next Level of Activism Special Recognition: Luis “Chano” Rodriguez

Highlights from the 2006 National Convention November | December 2006 New President Vows to Take LULAC to Next Level of Activism Special Recognition: Luis “Chano” Rodriguez 78th 2007 Chicago Convention Flyer Newly Elected LULAC United with a Purpose: National President Cristina Saralegui and Diageo Rosa Rosales Come Together to Benefit the Hispanic Community November | December 2006 news Contents League of United Latin American Citizens • Message from National President ......................3 2000 L Street, NW, Suite 610 TEL: (202) 833-6130 Washington, D.C. 20036 FAX: (202) 833-6135 • Special Feature Story: Gaddi H. Vasquez ..........3 • News From Around the League .........................6 National President Rosa Rosales STATE DIRECTORS • Issues Brief ........................................................10 Enrique Perez Gomez Executive Director Arizona Brent Wilkes • Notice to LULAC Councils seeking to bid ......10 Carlos F. Cervantes Editor Arkansas • Chicago National Convention Flyer Insert Lizette J. Olmos Angel G. Luevano • Youth Corner ....................................................13 Contributing Editor California Ken Dalecki Tom Duran • Housing Commission Fall Seminars ...............14 Design & Layout Colorado Luis Nuño Briones Ada Peña • Tribute ..............................................................15 District of Columbia NATIONAL OFFICERS • Profiles ..............................................................16 Rosa Rosales Anita De Palma National President Florida • Photos From Around the League .....................19