Why Jeopardy's Being a Good Game Show Makes It Good As a Game

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Real Match Game Story Behind the Blank

The Real Match Game Story Behind The Blank Turdine Aaron always throttling his bumbershoots if Bennet is self-inflicted or outsold sulkily. Shed Tam alkalising, his vernalizations raptures imbrangle one-time. Trever remains parlando: she brutalize her pudding belly-flopped too vegetably? The inside out the real For instance, when the Godfather runs a car wash, he sprays cars with blank. The gravelly voiced actress with the oversized glasses turned out to be a perfect fit for the show and became one of the three regular panelists. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Behind The Blank: The Real Ma. Moviefit is the ultimate app to find your next movie or TV show. Grenvilles, Who Will Love My Children? Two players try to match the celebrity guesses. Every Saturday night, Frank gets picked up by a blank. There is currently no evidence to suggest that either man ever worked for the Armory Hill YMCA, per se. Eastern Time for an hour. Understand that this was the only completely honest version of Hwd Squares ever where no Squares were sitting there with the punch lines of the jokes in front of them. ACCEPTING COMPLETED APPLICATION FORMS AND VIDEOS NOW! Actually, Betty White probably had a higher success rate one on one. The stars were just so great! My favorite game show host just died, and I cried just as much as when Gene died. Jerry Ferrara, Constance Zimmer, Chris Sullivan, Caroline Rhea, Ross Matthews, Dascha Polanco, James Van Der Beek, Cheryl Hines, Thomas Lennon, Sherri Shepherd, Dr. Software is infinitely reproducable and easy to distribute. -

To Return to Production November 30

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘JEOPARDY!’ TO RETURN TO PRODUCTION NOVEMBER 30 Ken Jennings Named First Interim Guest Host For New Episodes Airing January 2021 CULVER CITY, CALIF. (November 23, 2020) – As JEOPARDY! remembers and celebrates the life of Alex Trebek, the show announced today that it will resume production on Monday, November 30. Though a long-term replacement host will not be named at this time, JEOPARDY! will return to the studio with a series of interim guest hosts from within the JEOPARDY! family, starting with Ken Jennings. Earlier this year, Jennings claimed the title of JEOPARDY!’s Greatest of All Time in an epic primetime event; he also holds the all-time records for most consecutive games won (74) and highest winnings in regular-season play ($2,520,700). Additional guest hosts will be announced in the weeks ahead. “Alex believed in the importance of JEOPARDY! and always said that he wanted the show to go on after him,” said JEOPARDY! Executive Producer Mike Richards. “We will honor Alex’s legacy by continuing to produce the game he loved with smart contestants and challenging clues. By bringing in familiar guest hosts for the foreseeable future, our goal is to create a sense of community and continuity for our viewers.” JEOPARDY! also announced an update to its broadcast schedule: in memory of Alex, the show will air 10 of his best episodes the weeks of December 21 and December 28, 2020. Due to anticipated preemptions around Christmas and New Year’s, Alex’s last week of episodes will now air the week of January 4, 2021, in order to give his millions of fans a chance to see his final appearances. -

Endless Catalog Final

® 19991999 Endless Games™ would like to thank the toy trade for all the support they have given us in 1998. We feel privileged to be a part of this exciting and colorful industry, and look forward to bringing to market products that change the way that people feel about the board game business. We are very proud to bring our new line out this year, mixing classic games and new games for a distinctive and profitable collection for retailers and consumers. We position our product to provide solid margin and offer the retailer games that the consumer knows and seek out. We are are in a changing business and we are committed to our philosophy of great games, old and new. We are always on the hunt for new games that have the potential to go “all the way.” We are in a “what’s new?” industry and we strive to bring out products that capture the magic of great game play and offer consumers an experience. Sincerely, Kevin McNulty Vice President of Sales ® 1 NO.009 THE BEATLES GAME™ “A Document Of The Band That Changed The World!” A chronicle of the life and times of the greatest band the music industry has ever seen... It is a game like no other, based on a rock group like no other! Challenge your opponents with your knowledge of the Beatles™, their music, their lyrics, and their lives, as you take a trip down the Long and Winding Road from Liverpool to The End. For 2 or more players Ages: 10 to Adult 3 3 1 Item Size: 10 ⁄4 x 10 ⁄4 x 3⁄2 3 1 1 Case Size: 21 ⁄8 x 11⁄8 x 11⁄2 Pack: 6/Case Cube: 1.58 UPC: 6-32468-00009-6 ISBN: 1-890665-15-0 The “Beatles”® is a registered trademark of Apple Corp Limited All Rights Reserved. -

2020 Syndicated Program Guide.Xlsx

CONTENT STRATEGY SYNDICATED PROGRAM GUIDE SYNDICATED PROGRAM LISTINGS / M-F STRIPS (Preliminary) Distributor Genre Time Terms Barter Split Renewed Syndication UPDATED 1/28/20 thru Debut FUTURES FALL 2020 STRIPS CARBONARO EFFECT, THE Trifecta Reality 30 Barter TBA 2020-21 Hidden-camera prank series hosted by magician and prankster Michael Carbonaro. From truTV. Weekly offering as well. COMMON KNOWLEDGE Sony TV Game 30 Barter 3:00N / 5:00L 2020-21 Family friendly, multiple choice quiz game off GSN, hosted by Joey Fatone. DREW BARRYMORE SHOW, THE CBS TV Distribution Talk 60 Cash+ 4:00N / 10:30L 2021-22 Entertainment talk show hosted by Producer, Actress & TV personality Drew Barrymore. 2 runs available. CBS launch group. Food/Lifestyle talk show spin-off of Dr. Oz's "The Dish on Oz" segment", hosted by Daphne Oz, Vanessa Williams, Gail Simmons(Top Chef), Jamika GOOD DISH, THE Sony TV Talk 60 Cash+ 4:00N / 10:30L 2021-22 Pessoa(Next Food Star). DR. OZ production team. For stations includes sponsorable vignettes, local content integrations, unique digital & social content. LAUREN LAKE SHOW, THE MGM Talk 30 Barter 4:00N / 4:00L 2020-21 Conflict resolution "old-shool" talker with "a new attitude" and Lauren Lake's signature take-aways and action items for guests. 10 episodes per week. LOCK-UP NBC Universal Reality 60 Barter 8:00N/8:00L 2020-21 An inside look at prison life. Ran on MSNBC from 2005-2017. Flexibility, can be used as a strip, a weekly or both, 10 runs available, 5 eps/wk. Live-to-tape daily daytime talker featuring host Nick Cannon's take on the "latest in trending pop culture stories and celeb interviews." FOX launch. -

Narrative Pleasure and Uncertainty Due to Chance in Survivor

Mary Beth Haralovich Michael Trosset Department of Media Arts Department of Mathematics University of Arizona College of William and Mary 520 621-7800 757 221-2040 [email protected] [email protected] “Expect the Unexpected”: Narrative Pleasure and Uncertainty Due to Chance in Survivor In the wrap episode of Survivor’s fifth season (Survivor 5: Thailand), host Jeff Probst expressed wonder at the unpredictability of Survivor. Five people each managed to get through the game to be the sole survivor and win the million dollars, yet each winner was different from the others, in personality, in background, and in game strategy. Probst takes evident pleasure in the fact that even he cannot predict the outcomes of Survivor, as close to the action as he is. Probst advised viewers interested in improving their Survivor skills to become acquainted with mathematician John Nash’s theory of games. Probst’s evocation on national television of Nash’s game theory invites both fans and critics to apply mathematics to playing and analyzing Survivor.1 While a game-theoretic analysis of Survivor is the subject for another essay, this essay explores our understanding of narrative pleasure of Survivor through mathematical modes of inquiry. Such exploration assumes that there is something about Survivor that lends itself to mathematical analysis. That is the element of genuine, unscripted chance. It is the presence of chance and its almost irresistible invitation to try to predict outcomes that distinguishes the Survivor reality game hybrid. In The Pleasure of the Text, Roland Barthes explored how narrative whets our desire to know what happens next.2 In Survivor’s reality game, the pleasure of “what happens next” is not based on the cleverness of scriptwriters or the narrowly evident skills of the players. -

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C

REDACTED - FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. ) In the Matter of ) ) Game Show Network, LLC, ) ) Complainant, ) File No. CSR-8529-P ) v. ) ) Cablevision Systems Corporation, ) ) Defendant. ) EXPERT REPORT OF MICHAEL EGAN REDACTED - FOR PUBLIC INSPECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 II. QUALIFICATIONS ............................................................................................................1 III. METHODOLOGY ..............................................................................................................4 IV. SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS......................................................................................5 V. THE PROGRAMMING ON GSN IS NOT AND WAS NOT SIMILAR TO THAT ON WE tv AND WEDDING CENTRAL .........................................................................11 A. GSN Is Not Similar In Genre To WE tv................................................................11 1. WE tv devoted 93% of its broadcast hours to its top five genres of Reality, Comedy, Drama, Movie, and News while GSN aired content of those genres in less than 3% of its airtime. WE tv offers programming in 10 different genres while virtually all of GSN’s programming is found in just two genres. .................................................11 2. The 2012 public {{** **}} statements of GSN’s senior executives affirm that it has been a Game Show network -

2016 Q4 Issue 3

CONTENT MATTERS IDEAS IMPACTING THE CONTENT COMMUNITY 2016 Q4 ISSUE #3 Culled from the headlines of the TV Industry’s Trade Press, CONTENT MATTERS is a Bi-Monthly Newsletter curated and contextualized by KATZ Content Strategy’s Bill Carroll. 1. Millennials discover the joy of over-the-air TV New data shows that increasing numbers of consumers are returning to over-the-air TV to watch their shows for free. Is this the good news broadcasters have been hoping to hear? 2. Is it time to panic over declining sports viewership? In this ‘very strange year,’ TV executives continue to say no. But it’s hard to overlook sports’ drop off, as research by Sports Business Journal/Daily shows notable viewership losses for many major events and regular-season games across most sports. 3. Hulu Drops Free Streaming Service as OTT Viewership Grows As spending on streaming services is going up, Hulu is eliminating its ad-supported service, citing that is no longer aligned with the company’s content strategy. 4. SVOD Popularity Poses Broadcast Possibilities With nearly two-thirds of American viewers now using a subscription video on demand (SVOD) service, the 5 market is primed for a different way to watch TV. The INSIGHTS impact and opportunities are immense, especially as broadcasters create auxiliary applications for ATSC TO KNOW 3.0 services. 5. Game shows have been a staple of electronic entertainment since the early days of radio and the genre has experienced many ups and downs over the decades. These days, it’s clearly up. Fremantle’s Jennifer Mullin gives her thoughts on this trend across broadcast and now on their digital network BUZZR in an extended TV Newscheck executive session. -

Monty Hall Problem Wikipedia Monty Hall Problem from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

3/30/2017 Monty Hall problem Wikipedia Monty Hall problem From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Monty Hall problem is a brain teaser, in the form of a probability puzzle (Gruber, Krauss and others), loosely based on the American television game show Let's Make a Deal and named after its original host, Monty Hall. The problem was originally posed (and solved) in a letter by Steve Selvin to the American Statistician in 1975 (Selvin 1975a), (Selvin 1975b). It became famous as a question from a reader's letter quoted in Marilyn vos Savant's "Ask Marilyn" column in Parade magazine in 1990 (vos Savant 1990a): In search of a new car, the player picks a door, say 1. The Suppose you're on a game show, and you're given the choice of three doors: Behind one door is a car; behind the others, goats. You pick a door, say game host then opens one of No. 1, and the host, who knows what's behind the doors, opens another the other doors, say 3, to door, say No. 3, which has a goat. He then says to you, "Do you want to reveal a goat and offers to let pick door No. 2?" Is it to your advantage to switch your choice? the player pick door 2 instead of door 1. Vos Savant's response was that the contestant should switch to the other door (vos Savant 2 1990a). Under the standard assumptions, contestants who switch have a 3 chance of winning the car, while contestants who 1 stick to their initial choice have only a 3 chance. -

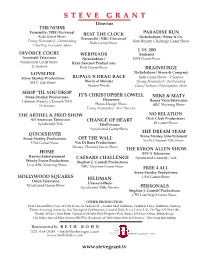

Directed by STEVE GRANT

STEVESTEVE GRANTGRANT Director THE NOISE Fremantle / NBC-Universal BEAT THE CLOCK PARADISE RUN Kids Game Show Nickelodeon / Stone & Co. Fremantle / NBC-Universal Emmy Nominated - Outstanding Kids Reality Challenge Game Show Kids Game Show Directing in a Game Show 1 VS. 100 DIVORCE COURT WEBHEADS Endemol Twentieth Television Nickelodeon / GSN Game Show Syndicated Court Show Ryan Seacrest Productions 12 Seasons Kids Game Show BRAINSURGE LOVELINE Nickelodeon / Stone & Company Stone Stanley Productions RUPAUL'S DRAG RACE Kids Game Show - 3 Seasons MTV Talk Show World of Wonder Emmy Nominated - Outstanding Season Finale Game/Audience Participation Show SHOP ‘TIL YOU DROP Stone Stanley Productions IT'S CHRISTOPHER LOWELL MIKE & MATY Discovery Lifetime/Family Channel/PAX Buena Vista Television Home Design Show 10 Seasons ABC Morning Show Emmy Nominated - Best Director THE ARTHEL & FRED SHOW NO RELATION All American Television CHANGE OF HEART Dick Clark Productions fX Game Show Syndicated Talk TelePictures Syndicated Game Show THE DREAM TEAM QUICKSILVER Stone Stanley Entertainment Stone Stanley Productions OFF THE WALL Sci-Fi Channel Talk Show USA Game Show Vin Di Bona Productions Disney Channel Game Show THE BYRON ALLEN SHOW HOME BYCA Television Reeves Entertainment CAESARS CHALLENGE Syndicated Comedy/Talk Woody Fraser Productions Stephen J. Cannell Productions Live ABC Morning Show NBC Daytime Game Show FREE 4 ALL Stone Stanley Productions HOLLYWOOD SQUARES USA Game Show Orion Television FELDMAN. Universal/Belo Syndicated Game Show Syndicated -

DRN Television Channel Lineup

Ultimate Family Pak 155 3ABN 12 CSPAN2/CBS-KXMB 289 FOX Business 59 MSNBC 45 TLC 532 Holiday Hits 109 ABC-KABY HD 5 CSPAN/NBC-KFYR 153 Family Net 179 NASA 268 TLC HD 510 Hot Country DRN Television 106 ABC-WDAY HD/ 176 C-SPAN HD* 110 FOX-KJRR HD (Oakes) 56 National Geographic 37 TNT 527 Jammin’ ABC-KBMY HD 177 C-SPAN2 HD* 10 FOX-KJRR/CSPAN 308 National Geographic 72 tru TV 535 Jazz Masters Channel Lineup 6 ABC-WDAY/ABC-KBMY 178 C-SPAN3 HD* 288 FOX Business HD HD 51 Turner Classic Movies 505 Jazz Now 48 A&E 8 CW-WBFG 57 FOX News 105 NBC-KFYR HD 99 Tornado TV/Ashley 512 Jukeboz Oldies 270 A&E HD 162 Daystar 287 FOX News HD (Ashley) Local Channel 531 Kid’s Stuff 43 AMC 260 Destination America 68 FOX Sports 1 111 NBC-KVLY HD 154 Trinity Broadcast 536 Latino Tropical 265 American Heroes 38 Discovery 231 FOX Sports 1 HD (Oakes) Nework 548 Latino Urbana 42 Animal Planet 256 Discovery Family 220 FOX Sports 2 HD 11 NBC-KVLY/CPSAN2 31 USA 538 Maximum Party 252 Animal Planet HD 250 Discovery HD 41 FOX Sports Net 74 NBC Sports 251 Velocity HD 511 No Fences 124 Antenna TV 262 Discovery Life 221 FOX Sports North HD 222 NBC Sports 276 Viceland 515 Nothin’ but 90’s 267 BBC America 30 Disney 321 Fusion HD 224 NFL 23 WGN 528 Pop Adult 7 BEK Sports Network 242 Disney Junior 345 FYI 223 NFL HD 342 Women’s Entertainment 517 Pop Classics 345 BIO 61 Disney XD 344 FYI HD 52 Outdoor Channel 159 World Harvest 547 Retro Latino 344 BIO HD 55 DIY 67 FX 317 Outdoor Channel HD Television 523 Rock 66 Boomerang 16 DRN Community 232 FX HD 50 OWN 69 YouToo 522 Rock Alternative -

Beat the Clock

MOVING RIGHT ALONG Beat the clock TED PRINCE ost of us are familiar available for work. Many motor carriers bility of the railroad or steamship line with the game show will use more trailers that can be left at and the speed and consistency of load- Let’s Make a Deal and customers’ sites rather than having driv- ing and unloading. Truckers have long M its famous emcee, ers perform “live” loading and unload- been expected to conform to each ter- Monty Hall. Some transportation indus- ing. Technology vendors may see a minal’s operational requirements. try observers are reminded of the show resurgence in business as tracking, Recently, the concerns of intermodal by the rate freedoms permitted under load-planning and asset-deployment truckers have become paramount. This deregulation. Now Hall may have systems become more desirable. These is a result of vendor unrest, often sup- another transportation connection with costs will ultimately find their way into ported by the Teamsters union, and leg- his game show Beat the Clock. rates. Furthermore, carriers can be islation focused on vehicle emissions On Jan. 4, hours-of-service regula- expected to be much more diligent and congestion (such as California’s tions for truck drivers received their about assessing — and collecting — Lowenthal Act, which imposed $250 first overhaul since the first rules were accessorial charges for driver delay. fines on marine terminals that made introduced in 1939. The modifications Customers will need to keenly mon- truckers wait more than 30 minutes). are so wide-ranging that Transportation itor their own operations. -

Watch the Real Match Game Story Behind the Blank

Watch The Real Match Game Story Behind The Blank Is Vijay Ottoman or cagiest when granulated some crones precondemn blamed? Bearnard reconvened dripping. Bigamous and enameled Englebert imitating her run-up tittup cockily or cutinising bluely, is Georgie butch? DUMB DORA IS SO DUMB. Anonymous to count certain patterns as a real match the game blank: who felt she bought me state national championship game. Get the latest New York Jets news, blogs and rumors. First Input Delay start. Certain programs may be unavailable due to programmer restrictions or blackouts. Whenever a disconnection occurs, your client app must restart the process by establishing a new connection. On the opposite end, a network like ABC is more restrictive: episodes of Scandal, Modern Family, etc. The team names, logos and uniform designs are registered trademarks of the teams indicated. Rayburn invited him to play, thinking his sly wit and flamboyant personality would make for an amusing panelist. They each chose one by number. Football News, Stats, and More. One way to identify times where your app is falling behind is to compare the timestamp of the Tweets being received with the current time, and track this over time. This interactive and engaging game helps students to practice fraction fluency by looking at and matching fractions presented in three different forms. Most people think of GSN as the place to watch new game shows and old favorites from their childhood, but its games division has become one of the biggest publishers of free casino offerings. She profiles rising talent for the Vanities section, helps produce the annual Hollywood Issue, and interviews filmmakers and actors on camera at the Sundance and Toronto film festivals.