1 the Orangi Pilot Project-Research and Training Institute's Mapping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan

Working Paper Series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies WORKING PAPER 15 Migration and small towns in Pakistan Arif Hasan with Mansoor Raza June 2009 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, dealing with urban planning and development issues in general, and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1982 and is a founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in Karachi, whose chairman he has been since its inception in 1989. He is currently on the board of several international journals and research organizations, including the Bangkok-based Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, and is a visiting fellow at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), UK. He is also a member of the India Committee of Honour for the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism. He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign CBOs, national and international NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. He has taught at Pakistani and European universities, served on juries of international architectural and development competitions, and is the author of a number of books on development and planning in Asian cities in general and Karachi in particular. He has also received a number of awards for his work, which spans many countries. Address: Hasan & Associates, Architects and Planning Consultants, 37-D, Mohammad Ali Society, Karachi – 75350, Pakistan; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Mansoor Raza is Deputy Director Disaster Management for the Church World Service – Pakistan/Afghanistan. -

East-Karachi

East-Karachi 475 476 477 478 479 480 Travelling Stationary Inclass Co- Library Allowance (School Sub Total Furniture S.No District Teshil Union Council School ID School Name Level Gender Material and Curricular Sport Total Budget Laboratory (School Specific (80% Other) 20% supplies Activities Specific Budget) 1 East Karachi Jamshed Town 1-Akhtar Colony 408070173 GBLSS - H.M.A. Middle Mixed 7,841 1,568 4,705 3,137 1,568 6,273 25,093 6,273 31,366 2 East Karachi Jamshed Town 2-Manzoor Colony 408070139 GBPS - BILAL MASJID NO.2 Primary Mixed 12,559 2,512 10,047 2,512 2,512 10,047 40,189 10,047 50,236 3 East Karachi Jamshed Town 2-Manzoor Colony 408070174 GBLSS - UNION Middle Mixed 16,613 3,323 13,290 3,323 3,323 13,290 53,161 13,290 66,451 4 East Karachi Jamshed Town 9-Central Jacob Line 408070171 GBLSS - BATOOL GOVT` BOYS`L/SEC SCHOOL Middle Mixed 12,646 2,529 10,117 2,529 2,529 10,117 40,466 10,117 50,583 5 East Karachi Jamshed Town 10-Jamshed Quarters 408070160 GBLSS - AZMAT-I-ISLAM Middle Boys 22,422 4,484 17,937 4,484 4,484 17,937 71,749 17,937 89,687 6 East Karachi Jamshed Town 10-Jamshed Quarters 408070162 GBLSS - RANA ACADEMY Middle Boys 13,431 2,686 8,059 5,372 2,686 10,745 42,980 10,745 53,724 7 East Karachi Jamshed Town 10-Jamshed Quarters 408070163 GBLSS - MAHMOODABAD Middle Boys 20,574 4,115 12,344 8,230 4,115 16,459 65,836 16,459 82,295 8 East Karachi Jamshed Town 11-Garden East 408070172 GBLSS - GULSHAN E FATIMA Middle Mixed 16,665 3,333 13,332 3,333 3,333 13,332 53,327 13,332 66,658 9 East Karachi Gulshan-e-Iqbal Town 3-PIB -

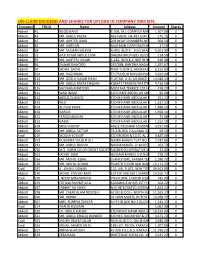

Un-Claim Dividend and Shares for Upload in Company Web Site

UN-CLAIM DIVIDEND AND SHARES FOR UPLOAD IN COMPANY WEB SITE. Company FOLIO Name Address Amount Shares Abbott 41 BILQIS BANO C-306, M.L.COMPLEX MIRZA KHALEEJ1,507.00 BEG ROAD,0 PARSI COLONY KARACHI Abbott 43 MR. ABDUL RAZAK RUFI VIEW, JM-497,FLAT NO-103175.75 JIGGAR MOORADABADI0 ROAD NEAR ALLAMA IQBAL LIBRARY KARACHI-74800 Abbott 47 MR. AKHTER JAMIL 203 INSAF CHAMBERS NEAR PICTURE600.50 HOUSE0 M.A.JINNAH ROAD KARACHI Abbott 62 MR. HAROON RAHEMAN CORPORATION 26 COCHINWALA27.50 0 MARKET KARACHI Abbott 68 MR. SALMAN SALEEM A-450, BLOCK - 3 GULSHAN-E-IQBAL6,503.00 KARACHI.0 Abbott 72 HAJI TAYUB ABDUL LATIF DHEDHI BROTHERS 20/21 GORDHANDAS714.50 MARKET0 KARACHI Abbott 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD616.00 KARACHI0 Abbott 96 ZAINAB DAWOOD 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD1,397.67 KARACHI-190 267/268, BANTWA NAGAR LIAQUATABAD KARACHI-19 Abbott 97 MOHD. SADIQ FIRST FLOOR 2, MADINA MANZIL6,155.83 RAMTLA ROAD0 ARAMBAG KARACHI Abbott 104 MR. RIAZUDDIN 7/173 DELHI MUSLIM HOUSING4,262.00 SOCIETY SHAHEED-E-MILLAT0 OFF SIRAJUDULLAH ROAD KARACHI. Abbott 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE14,040.44 APARTMENT0 PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. Abbott 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND4,716.50 KARACHI-74000.0 Abbott 135 SAYVARA KHATOON MUSTAFA TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND778.27 TOOSO0 SNACK BAR BAHADURABAD KARACHI. Abbott 141 WASI IMAM C/O HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA95.00 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE IST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHUDARABAD BRANCH BAHEDURABAD KARACHI Abbott 142 ABDUL QUDDOS C/O M HANIF ABDULLAH MOTIWALA252.22 MUSTUFA0 TERRECE 1ST FLOOR BEHIND UBL BAHEDURABAD BRANCH BAHDURABAD KARACHI. -

EAST), KARACHI IL� Main Building of DMC(East

DISTRICT MUNICIPAL CORPORATION (EAST), KARACHI IL Main Building of DMC(East). near KDA Police Station, Block-14, University Road, Karachi No.1.1 .I.FDMC(L)/?Q,'2016 Dated the 2 2- // .1'201 6 The Director (Assessment) SPPRA. 60\ emment of Sindh. Barrack No.08. Sindh Secretariat No.4-A Court Road.. Karachi. Sl'13.II CI - SUBMISSION OF TENDER DOCUMENTS Ref :- PS-SE/DM('/E/'2'372016 Dated:- . /vC/147- } Inclosed please find herewith I lard & Solt Copy 'off.. Press Clipping. including hill of quantities. hiddinu data. Contract Data . standard terms and condition 01 hiddin.ci_ documents volume-I. notification of procurement Committee. Redrassal Committee . Lliilibilit\ Minimum Qualification Criteria. haluation Criteria . Procurement Plane . & Rs:200() Pa\ order N1 hose date of openinu is Oil (19 12.'2016 are !ICI-L.1\ Sent \\ ith the request to upload on the WebsitL.• of SPPRA authority for \ our perusal and lqrther necessary action please. Executive Engineer {B&R} Jamshed /one D.M.C.( [AST) Copy for information to:- 1) The Chairman D.M.C.( Last) 2) I he Municipal Commissioner D 3) the Superintending luluincer Jamshed /one DM(' Last Office cop\ DISTRICT MUNICIPAL CORPORATION (EAST), KARACHI Main Building of DMC(East), near KDA Police Station, Block-14, University Road, Karachi 41 Telephone No.99230355 Fax No.99230871 No. PS/SE/DMC/East/ A9/6- 2016 Dated: /6'-//—-- TENDER NOTICE Single Stage Single Envelope Tender in sealed covers are invited on Schedule Rate Basis for the following works/jobs from the interested Firm/Bidders, according to he SPPRA Rules-2010(Amended 2013). -

Rapid Need Assessment Report Monsoon Rains Karachi Division Th Th 24 – 27 August 2020

Rapid Need Assessment Report Monsoon Rains Karachi Division th th 24 – 27 August 2020 Prepared by: Health And Nutrition Development Society (HANDS) Address: Plot #158, Off M9 (Karachi – Hyderabad) Motorway, Gadap Road, Karachi, Pakistan Web: www.hands.org.pk Email: [email protected] Ph: (0092-21) 32120400-9 , +92-3461117771 1 | P a g e Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Background............................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Objectives ............................................................................................................... 3 2. Methodology .................................................................................................................. 4 Situation at Model Town after Heavy Rains ....................................................................... 4 Situation at Model Town after Heavy Rains ....................................................................... 4 3. Findings ......................................................................................................................... 5 3.1. District East............................................................................................................. 6 3.2. Major disaterous events in East district ................................................................... 6 3.3. District Malir ........................................................................................................... -

An Overview 2017-2018

AN OVERVIEW 2017-2018 EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM The purpose of explanatory memorandum is to provide a guide to the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation annual budget. It entails budgetary planning and an over-view of the two major components of the budget: revenues and expenditure. It contains three main chapters: i. An Overview: Fiscal Policies of KMC. ii. Estimates of Receipts: Revenue resources of KMC and its analytical study. iii. Estimates of Expenditure: Current and Development of Expenditure and KMC’s obligatory Responsibilities. Explanatory Memorandum Page 1 AN OVERVIEW 2017-2018 Brief History. Board of Conservancy now Karachi Metropolitan Corporation. The local government institution as a basic democratic entity and as a basic administrative unit has been recognized all over the civilized world. The body which is elected by the residents on their own to regulate and manage public affairs and meet the need of local residents and to improve efficient service delivery at the local level to develop a sustainable quality of life for people. The Local Government in Karachi has a strong history. It can be claimed that Karachi is one of the few cities in the Indo-Pak sub-continent where municipal administration was established primitively during the early British Period, to cope with the epidemic of cholera, which was then ravaging the city. • In the year 1846 “Board of Conservancy” was established. • In the year 1852 the Board of Conservancy was converted in a “Municipal Commission” under the Municipal Act of 1850 with its temporary offices established at McLeod Road (the present I.I.Chundrigar Road). • In the year 1878, however the Bombay District Municipal Act (Act VI of 1873) was extended to Provence of Sindh areas including the “City Municipality of Karachi.” • The promulgation of Local Government legislation was continued when in the year 1933 the “City of Karachi Municipal Act, 1933” was promulgated and the “Municipal Corporation of the City of Karachi”came into being. -

Environment and Urbanization

Environment and Urbanization http://eau.sagepub.com/ Orangi Pilot Project: the expansion of work beyond Orangi and the mapping of informal settlements and infrastructure Arif Hasan Environment and Urbanization 2006 18: 451 DOI: 10.1177/0956247806069626 The online version of this article can be found at: http://eau.sagepub.com/content/18/2/451 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: International Institute for Environment and Development Additional services and information for Environment and Urbanization can be found at: Email Alerts: http://eau.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://eau.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://eau.sagepub.com/content/18/2/451.refs.html Downloaded from eau.sagepub.com by guest on June 15, 2011 Orangi Pilot Project: the expansion of work beyond Orangi and the mapping of informal settlements and infrastructure ARIF HASAN Arif Hasan is an architect ABSTRACT This paper describes the work of the Pakistan NGO, Orangi Pilot and planner in private Project–Research and Training Institute (OPP–RTI), in supporting improved practice in Karachi who provision for sanitation and other services in Orangi and other informal settle- has long worked closely ments in Karachi, and in other cities and smaller urban centres in Pakistan. It also with the Orangi Pilot describes an OPP–RTI programme to map and survey informal settlements in Project and with the Urban Resource Centre in Karachi Karachi, and the youth training programme that supported this, and also the (of which he is Chair). He is support for OPP–RTI partners in mapping in other urban centres. -

Creative Solutions R-3, Row-8, Block-C, National Cement Society, Block-10A, Gulshan-E-Iqbal, Karachi-Pakistan

Creative Solutions R-3, Row-8, Block-C, National Cement Society, Block-10A, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi-Pakistan. Mob: 0321-8222043 / Fax: 021-34984579 / Email: [email protected] Address : R-3, Row-8, Block-C, National Cement Society, Block-10A, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi-Pakistan. Mobile : 0321-8222043 Fax : 021-34984579 E-mail : [email protected] URL : www.creativesolutions.net.pk M/s Creative Solutions firm was established in the year 2007 with the object of providing Engineering & Consultancy Services in Electrical installation fields. Over the period of last five years the firm has achieved its goal of providing technical sound and safe Electrical installation services all over Karachi. We have a well equipped team of professional engineers, supervisors and workmen to plan & execute different jobs according to the requirements of our clients to achieve excellent engineering standards. We have undertaken almost all type of electrical jobs such as completion / execution of H.T, L.T Bulk supply sub-station, scheme works of all size of pole mounted Transformers, H.T, L.T panels, H.T, L.T cable laying & fixing work, Cellular Towers Electric connections, Dedicated PMT Schemes and maintenance of cellular towers power supply in Karachi. EXECUTED WORKS OF M/S TELENOR BTS POWER CONNECTIONS WITH DEDICATED PMT, L.T SPANS AND CABLE SCHEME CASES SCHEME CASES OF M/S TELENOR BTS TOWER POWER CONNECTIONS S.No Projects(Address) Description/ Job Executed 15 KVA Transformer with 2 H.T Spans of copper 01. Plot NO.R-211 P.R.E.C.H.S. Gulistan-e-Johar Karachi conductor 3 SWG and 2 H. -

1. Persons Interviewed

Karachi Transportation Improvement Project Final Report APPENDIX-1 MEETINGS 1. Persons Interviewed During the Phase 1 study period, which is Karachi Transport Master Plan-2030, JICA Study Team (JST) has been visited different organizations and Departments to collect data and also meet the officials. The list of these officials and their department/organization are given below 1.1 CDGK Administrator/ DCO, City District Government Karachi 1.1.1 KMTC Director General, Karachi Mass Transit Cell, CDGK Director, (Planning & Coordination) Karachi Mass Transit Cell, CDGK. Director (T), KMTC, CDGK 1.1.2 Master Plan Executive District Officer, Master Plan Group of Offices, CDGK District Officer, Master Plan Group of Offices, CDGK 1.1.3 Transport & Communication Executive District Officer, Transport Department , CDGK District Officer (Parking & Terminal Management), Transport & Communication Department (TCD), CDGK District Officer, Policy, Planning & Design, Transport & Communication Dept. CDGK 1.1.4 Education Department Executive District Officer, Education(School) , CDGK 1.1.5 Works & Service Department Executive District Officer, W&S , CDGK 1.2 DRTA Superintendant, District Regional Authority, CDGK 1.3 Town Administration Administrator, Keamari Town Administrator, Baldia Town Administrator, Bin Qasim Town Administrator, Gulberg Town Administrator, Gadap Town Administrator, Gulshan Town Administrator, Jamshed Town Administrator, Korangi Town Administrator, Landhi Town Administrator, Liaquatabad Town Appendix 1 - 1 Karachi -

Bus Routes Karachi January 2010

Bus Routes Karachi January 2010 Route #: 1-A Stops: Faqir Colony, Metroville, Bawany Ghali, Valika Mill, Habbib Bank, Petrol Pump, Lasbela, Sabilwali Masjid, Old Exhibition, Sadar, Frere Road, Burns Road, Bandar Road, Tower Route #: 1-B Stops: Nazimabd, Bara Maidan, Lasbela, Lawrence Road, Barness Street, Bandar Road, Tower Route #: 1-C Stops: M.P.R Colony, Qasba Colony, Banaras Colony, Pathan Colony, S.I.T.E, Habib Bank, Bismillah Hotel, Gandhi Garden, Garden Road, Plaza, Regal, Shahra-e-Liaquat, National Museum, Tower, Sultanabad Route #: 1-D Stops: Ittehad Town, Torri Chowk Sector II, Orangi Township, Banaras Colony, Pathan Colony, Petrol Pump, Liaquatabad No. 10, Liaquatabad, Post Office, Teen Hatti, Jehangir Road, Empress Market, Cantt Station Route #: 1-F Stops: Naval Colony, Mauripur, Gulbai Chowk, Tower, Juna Market, Ramswami, Garden Bara Board, Valika, Orangi Township No. 10 Route #: 1-G Stops: M.W Tower, Frere Road, Sadar, Numaish, Goro Mandir, Teen Hatti, Liaquat No. 10, Petrol Pump, Nazimabad No. 2, Gandhi Chowk, Paposh Nagar, Abdullah College, Metro Cinema, Data Chowk Orangi Town Route #: 1-H Stops: Gulshan-e-Bahar, Orangi Sector No. 14, Orangi Sector No. 13, Orangi Sector No. 7, Orangi Sector No. 5, Qadafi Chowk, Qasba Mour, Banaras Colony, Valika Hospital, Valika Mill, Habib Bank, S.I.T.E, Post Office, Maroon Mill, Laltain Factory, Ghani Chowk, Shershah, Miran Naka, Chakiwara, Lee Market, Kharadar, Jamat Khana, Tower Route #: 1-K Stops: Tower, Regal Cinema, Plaza, Garden, Pakistan Quarters, Bara Board, Banaras, Qasba Mour, -

JBES-Vol-12-No-2-P-1

J. Bio. & Env. Sci. 2018 Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences (JBES) ISSN: 2220-6663 (Print) 2222-3045 (Online) Vol. 12, No. 2, p. 117-127, 2018 http://www.innspub.net RESEARCH PAPER OPEN ACCESS Physico-Chemical analysis of bore water from different regions of Karachi, Pakistan Kashif Ahmed*, Hafiz Abdul Rehman, Nuzhat Arshad, Sobia Israr Department of Chemistry, NED University of Engineering and Technology, Karachi, Pakistan Article published on February 28, 2018 Key words: Bore water, Physico-Chemical analysis, Heavy metal analysis, Pakistan Standard for Drinking Water (PSDW) and WHO. Abstract Pure water for drinking and domestic purpose is the basic requirement for healthy life. However, increase in water pollution decrease the pure water resources and become a challenge for pure water and besides contaminated water created health hazard problems. In this study, we collect bore water samples from different regions of Karachi including Jamshad Town, DHA and Korangi Industrial Area. These bore water used in homes for cleaning purpose, in some area for drinking purpose and in some industries for Reverse Osmosis feed water for producing drinking and portable water. This research investigates the physico-chemical and heavy metals analysis embraces; appearance, color, odor, taste, pH, TDS, total hardness of Chloride, Total Alkalinity, Sulfate, Turbidity, Phosphate, Iron, Chromium, Lead and Zinc in the water. Heavy metals of bore water observed within limit while TDS, Hardness, Chloride. Sulfate and turbidity of most of samples found very high and unacceptable for drinking purpose as per limits which are specified by WHO and PSDW. Physico-chemical parameters analyzed by titration method and Spectrophotometer method while Heavy metals determine by Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer method. -

Appendix VII Bank Wise Atms¶ Locations As on 31St December 2011

Appendix VII %DQN:LVH$70V¶/RFDWLRQV As on 31st December 2011 Depalpur Albaraka Bank Abdul Hakim (Pakistan) Ltd. (35) Adda Nandi Pur Dera Ghazi Khan (2) Ahmedpur East -Azmat Road Daska Akalgarh A.K. -Model Town Faisalabad Akwal Gujranwala Alipur Chatha Dhangri Bala A.K. Hyderabad Arifwala Dhudial, District Chakwal Attock Isalmabad (3) Bagh Di Khan (2) -F-7 Jinnah Super Markaz Bahawal Nagar -Circular Road -Jinnah Avenue Blue Area -Khalid Market, Laghari Gate -Shifa International Hospital, Bahawalpur (4) -Dubai.Chowk Bwp Dina Karachi (12) -Farid Gate Bwp Dinga -Banglore Town, Main Shahrah e Faisal, -Grain Market, Dunyapur -Block-7, F. B. Area, -S.Town Bwp Ellahabad -Boat Basin, Block 5, Clifton -Fiver Star Chowrangi, Balakot Faisalabad (25) -Korangi Industrial Area, Bannu -15 Club Road, -Main Branch, Al Farid Center, PIDC Bara Kahu -Canal Road, Faialabad -Main Khayabane Shahbaz Phase VI Bhakkar -Chibban, -Nishat Lane No.4, Phase-VI, DHA, -Factory Area. -Phase-II, D.H.A, Bhalwal (2) -Ghulam Muhammad Abad. -Shaheed-e-Millat Road, -Liaqat Shaheed Road -Gole Cloth Market, -Site Area, -Noor Hayat Colony -Gole Karyana. -University Road, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, -Gulberg Colony. Bhirya -Gulistan Colony (Akbar Chowk). Lahore (7) -Jaranwala Road. -Allama Iqbal Town, Gulshan Block Burewala (2) -Jinnah Colony -Block R-1, Johar Town, - Grain Market -Kotwali Road. -Block-Y, Phase III, DHA, -Housing Scheme -Madina Town (Bismillah Chowk). -Cavalry Ground Lahore -Main Bazar, Chak Jhumra, -DHA S Block Chak No.61 Rb (2) Khurrianwala -M.M. Alam Road Gulberg III, -Sheikhupura Road, Jaranwala (2) -Manawala. -Shadman Colony -Model Branch, Kotwali Road. Chakswari A.K.