Pop Music and the Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Wanna Be Me”

Introduction The Sex Pistols’ “I Wanna Be Me” It gave us an identity. —Tom Petty on Beatlemania Wherever the relevance of speech is at stake, matters become political by definition, for speech is what makes man a political being. —Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition here fortune tellers sometimes read tea leaves as omens of things to come, there are now professionals who scrutinize songs, films, advertisements, and other artifacts of popular culture for what they reveal about the politics and the feel W of daily life at the time of their production. Instead of being consumed, they are historical artifacts to be studied and “read.” Or at least that is a common approach within cultural studies. But dated pop artifacts have another, living function. Throughout much of 1973 and early 1974, several working- class teens from west London’s Shepherd’s Bush district struggled to become a rock band. Like tens of thousands of such groups over the years, they learned to play together by copying older songs that they all liked. For guitarist Steve Jones and drummer Paul Cook, that meant the short, sharp rock songs of London bands like the Small Faces, the Kinks, and the Who. Most of the songs had been hits seven to ten 1 2 Introduction years earlier. They also learned some more current material, much of it associated with the band that succeeded the Small Faces, the brash “lad’s” rock of Rod Stewart’s version of the Faces. Ironically, the Rod Stewart songs they struggled to learn weren’t Rod Stewart songs at all. -

In Less Than a Decade, DUFF Mckagan Shot

36-43 Duff feature 3/16/04 2:10 PM Page 36 36-43 Duff feature 3/16/04 2:14 PM Page 37 Bulletproof In less than a decade, DUFF McKAGAN shot from strung-out GUNS N’ ROSES megastar to sober bass-groovin’ dude for VELVET REVOLVER. Bass Guitar’s E.E. Bradman gets the rock-solid bass man in his sight. BG 37 36-43 Duff feature 3/16/04 4:25 PM Page 38 36-43 Duff feature 3/16/04 5:22 PM Page 39 “Every good rock band has to . You need that something that moves people.” uff McKagan knows covers-only Spaghetti Incident and the so-so Live Era didn’t measure up to the band’s HAIR FORCE ONE: about missed opportuni- Duff, with Rose and Slash, debut, and by 1992 Izzy and Adler had been in his GN’R daze ties. He was, after all, the replaced by Gilby Clarke and Matt Sorum. In founding bassist of the 1993, McKagan released his first solo album, legendary Guns N’ Roses, Believe in Me. Guns eventually crumbled, leaving an uncompleted (and still unreleased) whose rock-star excesses, album, tentatively titled Chinese Democracy, volatile live shows and incendiary in the balance. albums made them the biggest band in McKagan’s second effort, Beautiful D Disease, was lost to record company politics, the world before they spluttered to a but he stayed busy producing Betty Blow- messy close a decade later. But McKa- torch, playing several instruments with gan—who after a drug-and-alcohol- Screaming Trees vocalist Mark Lanegan, and related pancreas explosion 10 years ago handling guitar and bass duties for Iggy Pop, was told by doctors that his next drink Ten Minute Warning, Loaded, the Neurotic Outsiders (with John Taylor of Duran Duran would kill him—also knows a thing or and Steve Jones of the Sex Pistols) and the two about second chances. -

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

Marc Brennan Thesis

Writing to Reach You: The Consumer Music Press and Music Journalism in the UK and Australia Marc Brennan, BA (Hons) Creative Industries Research and Applications Centre (CIRAC) Thesis Submitted for the Completion of Doctor of Philosophy (Creative Industries), 2005 Writing to Reach You Keywords Journalism, Performance, Readerships, Music, Consumers, Frameworks, Publishing, Dialogue, Genre, Branding Consumption, Production, Internet, Customisation, Personalisation, Fragmentation Writing to Reach You: The Consumer Music Press and Music Journalism in the UK and Australia The music press and music journalism are rarely subjected to substantial academic investigation. Analysis of journalism often focuses on the production of news across various platforms to understand the nature of politics and public debate in the contemporary era. But it is not possible, nor is it necessary, to analyse all emerging forms of journalism in the same way for they usually serve quite different purposes. Music journalism, for example, offers consumer guidance based on the creation and maintenance of a relationship between reader and writer. By focusing on the changing aspects of this relationship, an analysis of music journalism gives us an understanding of the changing nature of media production, media texts and media readerships. Music journalism is dialogue. It is a dialogue produced within particular critical frameworks that speak to different readers of the music press in different ways. These frameworks are continually evolving and reflect the broader social trajectory in which music journalism operates. Importantly, the evolving nature of music journalism reveals much about the changing consumption of popular music. Different types of consumers respond to different types of guidance that employ a variety of critical approaches. -

Wade Gordon James Nelson Concordia University May 1997

Never Mind The Authentic: You Wanted the Spectacle/ You've Got The Spectacle (And Nothing Else Matters?) Wade Gordon James Nelson A Thesis in The Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts ai Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada May 1997 O Wade Nelson, 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 191 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Weliington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your hie Votre réference Our file Notre reldrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of ths thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fh, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fomat électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in thi s thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thése. thesis nor substantiai extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Never Mind The Authentic: You Wanted The Spectacle/ Y ou've Got The Spectacle (And Nothing Else Matters?) Wade Nelson This thesis examines criteria of valuation in regard to popular music. -

The Rolling Stones and Performance of Authenticity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies Art & Visual Studies 2017 FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY Mariia Spirina University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2017.135 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Spirina, Mariia, "FROM BLUES TO THE NY DOLLS: THE ROLLING STONES AND PERFORMANCE OF AUTHENTICITY" (2017). Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies. 13. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/art_etds/13 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art & Visual Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Art & Visual Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Art to Commerce: the Trajectory of Popular Music Criticism

Art to Commerce: The Trajectory of Popular Music Criticism Thomas Conner and Steve Jones University of Illinois at Chicago [email protected] / [email protected] Abstract This article reports the results of a content and textual analysis of popular music criticism from the 1960s to the 2000s to discern the extent to which criticism has shifted focus from matters of music to matters of business. In part, we believe such a shift to be due likely to increased awareness among journalists and fans of the industrial nature of popular music production, distribution and consumption, and to the disruption of the music industry that began in the late 1990s with the widespread use of the Internet for file sharing. Searching and sorting the Rock’s Backpages database of over 22,000 pieces of music journalism for keywords associated with the business, economics and commercial aspects of popular music, we found several periods during which popular music criticism’s focus on business-related concerns seemed to have increased. The article discusses possible reasons for the increases as well as methods for analyzing a large corpus of popular music criticism texts. Keywords: music journalism, popular music criticism, rock criticism, Rock’s Backpages Though scant scholarship directly addresses this subject, music journalists and bloggers have identified a trend in recent years toward commerce-specific framing when writing about artists, recording and performance. Most music journalists, according to Willoughby (2011), “are writing quasi shareholder reports that chart the movements of artists’ commercial careers” instead of artistic criticism. While there may be many reasons for such a trend, such as the Internet’s rise to prominence not only as a medium for distribution of music but also as a medium for distribution of information about music, might it be possible to discern such a trend? Our goal with the research reported here was an attempt to empirically determine whether such a trend exists and, if so, the extent to which it does. -

MUSIC PREVIEW Debut Single, “Homesick.” After Going Viral on Tiktok King’S First Single Released to Country

MIRANDA LAMBERT MAREN MORRIS RACHEL WAMMACK TENILLE TOWNES KAT (OF KAT & ALEX) PISTOL ANNIES HANNAH DASHER GEORGIA WEBSTER ELLE KING MIRANDA LAMBERT MAREN MORRIS RACHEL WAMMACK TENILLE TOWNES KAT (OF KAT & ALEX) PISTOL ANNIES HANNAH DASHER GEORGIA WEBSTER ELLE KING LET’S GROW, GIRLS Labels share what to expect from the women on their rosters in 2021 and beyond 19th & Grand out June 25. Pearce returns to the road in late July as Broken Bow Coming off her first No. 1 at direct support for the upcoming Lady A: What A Song Can Do Tour. Lainey Wilson knows some Country radio with “Somebody things a man … and woman … Like That” and an ACM New Callista Clark is already Top 40 with her debut single, “It’s ‘Cause I Am.” Chosen by the majority of oughta know. Called a “song Female Artist nomination, every country fan needs to hear” Tenille Arts is set to release her broadcast companies as a new music initiative and most recently selected as iHeartCountry’s On The (Taste of Country) and a “must third studio album later this year. listen” (Rolling Stone), “Things A “Back Then, Right Now” is the Verge artist, the 17-year-old is Man Oughta Know” is climbing Lainey lead single. “With the success of celebrating the release of her Tenille Arts through the teens. And she’s Wilson ‘Somebody Like That’ breaking debut collection, Real To Me. “The thing that sets Callista just getting started, according records across the board, it to VP/Promotion Lee Adams: becomes the highest-charting song and the only No. -

Composing Outside the Beatles

FAME Review: Composing Outside the Beatles - Lennon & McCartney: ... http://www.acousticmusic.com/fame/p06071.htm Composing Outside the Beatles: Lennon & McCartney: 1967 - 1972 PGDVD126 (DVD) Available from MVD Entertainmant Group . A review written for the Folk & Acoustic Music Exchange by Mark S. Tucker ([email protected] ). A while back, I critiqued Composing the Beatles Songbook: Lennon and McCartney 1966 - 1970 , a very compelling DVD making the case that Paul McCartney was much more responsible for many of the duo's successes than has been formerly credited. Even should one disagree with that historic supposition, Songbook was very difficult to argue with. Of the half dozen other critics I've loaned the disc to, all have remarked on the changes it wrought in their thinking. Now, Composing: 1967 - 1972 performs a sort of sanction and claims that it was not only Paul and John who broke the Beatles up, but more Yoko, as has been folklorically assumed, though Paul is enigmatically cited as more contributive than John. Well, that's the initial case anyway, just as the film opens, later reversed deep into the flick (the true explanation of Paul's quitting being revealed). As this very interesting document proceeds, however, Lennon, McCartney, and Ono all come in for a bit of a drubbing…though Yoko fares worst of all. Making the case is an assortment of critics, including Robert Christgau and Jon Pareles, as well as a few musicians (Klaus Voorman, Alan White, and Denny Seiwell) who were right there when everything was happening. The insights are first-person and well formulated—in the musicians' case, from experience and involvement. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS FEBRUARY 24, 2020 | PAGE 1 OF 19 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] It’s Sam Hunt, Country Radio Seminar: An Older Folks >page 4 Medium Looks For Youthful Passion Positive Thoughts From CRS Mickey Guyton has yet to earn a hit record, but she still reaches the masses, remaining the most-listened-to media, >page 10 commandeered a standing ovation from broadcasters with a but the actual time spent listening is dwindling, and 18- to new song that was widely regarded as the stand-out musical 34-year-old country fans now devote more time to streaming moment of Country Radio Seminar. in an average week than they do to traditional broadcast radio. Was it a breakthrough moment? That can only be assessed by Additionally, programmers’ beliefs about the audience have not A Drink And A Nod programmers’ responses in the weeks and months ahead, but it kept up with changes in the playing field, or even their customers’ To Warner subtly pointed to radio’s current challenge: Do broadcasters play definition of radio. >page 11 it safe in a crowded media field? Or do they take a chance on a Younger listeners no longer view radio as a place that transmits talented artist who took her own risk on a song music from a tower, researcher Mark Ramsey that has the potential to change a listener’s life? said while unveiling a study of how consumers’ Guyton belted a gut-wrenching piano ballad, perceptions of broadcasting differ with PDs’ Big Machine’s New “What Are You Gonna Tell Her,” during the expectations. -

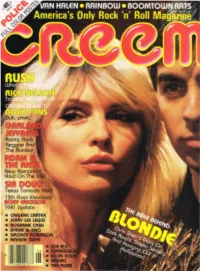

RUSH: but WHY ARE THEY in SUCH a HURRY? What to Do When the Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•

• CARLENE CARTER • JERRY LEE LEWIS • ROSANNE CASH • BYRNE & ENO • SMOKEY acMlNSON • MARVIN GAYE THE SONG OF INJUN ADAM Or What's A Picnic Without Ants? .•.•.•••••..•.•.••..•••••.••.•••..••••••.•••••.•••.•••••. 18 tight music by brit people by Chris Salewicz WHAT YEAR DID YOU SAY THIS WAS? Hippie Happiness From Sir Doug ....••..•..••..•.••••••••.•.••••••••••••.••••..•...•.••.. 20 tequila feeler by Toby Goldstein BIG CLAY PIGEONS WITH A MIND OF THEIR OWN The CREEM Guide To Rock Fans ••.•••••••••••••••••••.•.••.•••••••.••••.•..•.•••••••••. 22 nebulous manhood displayed by Rick Johnson HOUDINI IN DREADLOCKS . Garland Jeffreys' Newest Slight-Of-Sound •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.••..••. 24 no 'fro pick. no cry by Toby Goldstein BLONDIE IN L.A. And Now For Something Different ••••.••..•.••.••.•.•••..••••••••••.••••.••••••.••..••••• 25 actual wri ting by Blondie's Chris Stein THE PSYCHEDELIC SOUNDS OF ROKY EmCKSON , A Cold Night For Elevators •••.••.•••••.•••••••••.••••••••.••.••.•••..••.••.•.•.••.•••.••.••. 30 fangs for the memo ries by Gregg Turner RUSH: BUT WHY ARE THEY IN SUCH A HURRY? What To Do When The Snow-Dog Bites! •••.•.••••..•....••...••••••.•.•••...•.•.•..•. 32 mortgage payments mailed out by J . Kordosh POLICE POSTER & CALENDAR •••.•••.•..••••••••••..•••.••.••••••.•••.•.••.••.••.••..•. 34 LONESOME TOWN CHEERS UP Rick Nelson Goes Back On The Boards .•••.••••••..•••••••.••.•••••••••.••.••••••.•.•.. 42 extremely enthusiastic obsewations by Susan Whitall UNSUNG HEROES OF ROCK 'N' ROLL: ELLA MAE MORSE .••.••••.•..•••.••.• 48 control -

Issue 6 £1.50

Issue 6 £1.50 "THE ALTERNATIVE TO CREEM" e h , r e m u s n o c e h t o t t c u d o r p s i h l l e s t ' n s e o d t n a h c r e m k n u j e h T “ sells the consumer to his product. He does not improve and improve not does He product. his to consumer the sells You're my kinda scum... kinda my You're most esteemed rag and the weirdo's who wrote it. it. wrote who weirdo's the and rag esteemed most obvs). This is my not-so-subtle nod to that once once to that nod is my not-so-subtle This obvs). writing goes, is Creem Magazine (pre-shittening, (pre-shittening, is Magazine goes, Creem writing Single Single Malt but one of the main things, as far unfluenced by all sorts of shit, from Sabbath to Sabbath from of shit, by sorts all unfluenced new new mascot, Cap'n Elmlee. Why? Well, I'm the the cover. I'm pleased to introduce you to our You You may also have noticed the cheeky chappie on n' greet. n' time you get invited to your local sex cult meet meet cult sex local to your invited get you time stick by us you won't look like such a noob next next a noob such like look won't you us by stick rama rama starting on page 4, meaning that if you kick kick off a new feature, a veritable sleaze-o- Bloodbath's Bloodbath's done-gone global! Oh yeah, and we Saturn from the California branch.