Alex Danco Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7. Annie's Song John Denver

Sing-Along Songs A Collection Sing-Along Songs TITLE MUSICIAN PAGE Annie’s Song John Denver 7 Apples & Bananas Raffi 8 Baby Beluga Raffi 9 Best Day of My Life American Authors 10 B I N G O was His Name O 12 Blowin’ In the Wind Bob Dylan 13 Bobby McGee Foster & Kristofferson 14 Boxer Paul Simon 15 Circle Game Joni Mitchell 16 Day is Done Peter Paul & Mary 17 Day-O Banana Boat Song Harry Belafonte 19 Down by the Bay Raffi 21 Down by the Riverside American Trad. 22 Drunken Sailor Sea Shanty/ Irish Rover 23 Edelweiss Rogers & Hammerstein 24 Every Day Roy Orbison 25 Father’s Whiskers Traditional 26 Feelin’ Groovy (59th St. Bridge Song) Paul Simon 27 Fields of Athenry Pete St. John 28 Folsom Prison Blues Johnny Cash 29 Forever Young Bob Dylan 31 Four Strong Winds Ian Tyson 32 1. TITLE MUSICIAN PAGE Gang of Rhythm Walk Off the Earth 33 Go Tell Aunt Rhody Traditional 35 Grandfather’s Clock Henry C. Work 36 Gypsy Rover Folk tune 38 Hallelujah Leonard Cohen 40 Happy Wanderer (Valderi) F. Sigismund E. Moller 42 Have You ever seen the Rain? John Fogerty C C R 43 He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands American Spiritual 44 Hey Jude Beattles 45 Hole in the Bucket Traditional 47 Home on the Range Brewster Higley 49 Hound Dog Elvis Presley 50 How Much is that Doggie in the Window? Bob Merrill 51 I Met a Bear Tanah Keeta Scouts 52 I Walk the Line Johnny Cash 53 I Would Walk 500 Miles Proclaimers 54 I’m a Believer Neil Diamond /Monkees 56 I’m Leaving on a Jet Plane John Denver 57 If I Had a Hammer Pete Seeger 58 If I Had a Million Dollars Bare Naked Ladies 59 If You Miss the Train I’m On Peter Paul & Mary 61 If You’re Happy and You Know It 62 Imagine John Lennon 63 It’s a Small World Sherman & Sherman 64 2. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Music Tech Lesson Plan

Music Tech Lesson Plan Better than the original? Cover version showdown Listening and responding Grade level 5-10 Objective Students will analyse two versions of the same song and use musical terminology to describe to identify the musical differences and similarities. USA Music ● 6. Listening to, analyzing, and describing music. Education Standards Australian Music ● 6.3 Rehearse and perform music, including music they Curriculum have composed, by improvising, sourcing and arranging Standards ideas and making decisions to engage an audience ● 8.6 Analyse composers’ use of the elements of music and stylistic features when listening to and interpreting music ● 10.6 Evaluate a range of music and compositions to inform and refine their own compositions and performances Materials/Equipment ● Youtube video/s or audio recordings of an original song and a cover version of that song (some suggestions below, but you can use songs of your choice) ● Computer or other device connected to the internet, plus data projector and speakers if watching/listening as a class ● Student devices connected to the internet if students will be watching/listening individually or in small groups ● Attached worksheet - printed copies for students to fill out, or digital copies that can be completed on their tablet devices Duration 1 lesson Skills required Students should have an understanding of the following musical concepts: tempo, rhythm, melody, pitch, mood/feel and style Procedure Select songs - original and cover version ● This lesson is adaptable so you can use -

Coca-Cola Stage Backgrounder 2016

May 26, 2016 BACKGROUNDER 2016 Coca-Cola Stage lineup Christian Hudson Appearing Thursday, July 7, 7 p.m. Website: http://www.christianhudsonmusic.com/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ChristianHudsonMusic Twitter: www.twitter.com/CHsongs While most may know Christian Hudson by his unique and memorable performances at numerous venues across Western Canada, others seem to know him by his philanthropy. This talented young man won the prestigious Calgary Stampede Talent Show last summer but what was surprising to many was he took his prize money of $10,000 and donated it all to the local drop-in centre. He was touched by the stories he was told by a few people experiencing homelessness he had met one night prior to the contest’s finale. His infectious originals have caught the ears of many in the industry that are now assisting his career. He was honoured to receive 'The Spirit of Calgary' Award at the inaugural Vigor Awards for his generosity. Hudson will soon be touring Canada upon the release of his first single on national radio. JJ Shiplett Appearing Thursday, July 7, 8 p.m. Website: http://www.jjshiplettmusic.com/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/jjshiplettmusic/ Twitter: www.twitter.com/jjshiplettmusic Rugged, raspy and reserved, JJ Shiplett is a true artist in every sense of the word. Unapologetically himself, the Alberta born singer-songwriter and performer is both bold in range and musical creativity and has a passion and reverence for the art of music and performance that has captured the attention of music fans across the country. He spent the major part of early 2016 as one of the opening acts on the Johnny Reid tour and is also signed to Johnny Reid’s company. -

Marianas Trench

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: PRESENTS MARIANAS TRENCH NEVER SAY DIE TOUR WITH VERY SPECIAL GUESTS WALK OFF THE EARTH WEDNESDAY, MARCH 30, 2016 ENMAX CENTRIUM, WESTERNER PARK – RED DEER, AB Doors: 6:00PM Show: 7:00PM TICKETS ON SALE FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 13 @ 12PM-NOON www.livenation.com Charge by Phone 1-855-985-5000 Tickets also available at all Ticketmaster Outlets Tickets (incl. GST) $35.00, $49.50, $65.00 (Plus FMF & Service charges) **RESERVED SEATING / ALL AGES** Announced today, Multi-Platinum selling Canadian pop-rockers Marianas Trench will head out on their Never Say Die tour across Canada in the spring of 2016. Tickets for the tour will go on sale November 13 via www.livenation.com, with a VIP presale on November 10. The tour is in support of their newly released fourth studio album Astoria (604 Records / Universal Music Canada / Interscope), which debuted at #2 on the Canadian SoundScan charts and roared onto the American Top Current Albums Chart at #33. The release echoes one part 1980’s fantasy adventure film and one part classic Marianas Trench and American fans are currently enjoying this experience first-hand as the band embarked on their U.S tour last week. Kicking off on March 9 in Kingston, ON, the 18-date tour will showcase the hard work and passion put into their latest offering, and promises to be one of their most exciting tours to date. Joining the band on tour is Platinum selling Canadian quintet Walk Off The Earth. Touring in support of their latest single “Hold On,” WOTE has garnered close to half a billion total YouTube views and more than 2 million YouTube subscribers. -

An Analysis on Youtube Rewinds

KADİR HAS UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES NEW MEDIA DISCIPLINE AREA POPULAR CULTURE REPRESENTATION ON YOUTUBE: AN ANALYSIS ON YOUTUBE REWINDS SİDA DİLARA DENCİ SUPERVISOR: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Çiğdem BOZDAĞ MASTER’S THESIS ISTANBUL, AUGUST, 2017 i POPULAR CULTURE REPRESENTATION ON YOUTUBE: AN ANALYSIS ON YOUTUBE REWINDS SİDA DİLARA DENCİ SUPERVISOR: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Çiğdem BOZDAĞ MASTER’S THESIS Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences of Kadir Has University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s in the Discipline Area of New Media under the Program of New Media. ISTANBUL, AUGUST, 2017 i ii iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract Acknowledgements List of Figures List of Chapters 1. Introduction 2. Literature Review 2.1 Commercializing Culprit or Social Cement? What is Popular Culture? 2.2 Sharing is caring: user-generated content 2.3 Video sharing hype: YouTube 3. Research Design 3.1 Research Question 3.2 Research Methodology 4. Research Findings and Analysis 4.1 Technical Details 4.1.1 General Information about the Data 4.1.2 Content Analysis on Youtube Rewind Videos 5. Conclusion References iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first and foremost like to thank my thesis advisor Assoc. Prof. Dr. Çiğdem BOZDAĞ of the Faculty of Communication at Kadir Has University. Prof. Bozdağ always believed in me even I wasn’t sure of my capabilities. She kindly guided me through the tunnel of the complexity of writing a thesis. Her guidance gave me strength to keep myself in right the direction. I would like to thank Assoc. Prof. Dr. Eylem YANARDAĞOĞLU whose guidance was also priceless to my studies. -

View Live Music Index

GREATER HAMILTON’S INDEPENDENT VOICE AUGUST 8 — 14, 2019 VOL. 25 NO. 31 Walls COMPLETE ENTERTAINMENTTAINMENT FREEFREELISTINGS EVEREVERYY THURSDAY RULES • SILVERTONE HILLS • HOBBS AND SHAW • HAMLET • KEY FOR TWO • RUNNING AWAY FROM GUNS • ASTROLOGY 2 AUGUST 8 — 14, 2019 VIEW VIEW AUGUST 8 — 14 2019 3 THEATRE 05 HAMLET INSIDE THIS ISSUE AUGUST 8— 14, 2019 08 COVER PALE DRONE Cover Photo: Mike Thoang FORUM FOOD 05 PERSPECTIVE Running From Guns 10 Dining Guide 18 EARTH TALK Glamping MOVIES MUSIC 16 REVIEW Hobbs And Shaw 08 Hamilton Music Notes 17 Movie Reviews 11 Live Music Listing ETC. MUSIC 18 General Classifieds 05 THEATRE Hamlet 19 Free Will Astrology 07 THEATRE Key For Two 19 Adult Classifieds 370 MAIN STREET WEST, HAMILTON, ONTARIO L8P 1K2 HAMILTON 905.527.3343 FAX 905.527.3721 VIEW FOR ADVERTISING INQUIRIES: 905.527.3343 X102 EDITOR IN CHIEF Ron Kilpatrick x109 [email protected] OPERATIONS DIRECTOR CLASSIFIED ADVERTISING ACCOUNTING PUBLISHER Marcus Rosen x101 Liz Kay x100 Roxanne Green x103 Sean Rosen x102 [email protected] 1.866.527.3343 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ADVERTISING DEPT DISTRIBUTION CONTRIBUTORS LISTINGS EDITOR RandA distribution Rob Breszny • Gregory SENIOR CORPORATE Alison Kilpatrick x100 Owner:Alissa Ann latour Cruikshank • Sara Cymbalisty • REPRESENTATIVE [email protected] Manager:Luc Hetu Maxie Dara • Albert DeSantis • Ian Wallace x107 905-531-5564 Darrin DeRoches • Daniel [email protected] HAMILTON MUSIC NOTES [email protected] Gariépy • Allison M. Jones • Tamara Kamermans • Michael Ric Taylor Klimowicz • Don McLean ADVERTISING [email protected] PRINTING • Brian Morton • Ric Taylor • REPRESENTATIVE MasterWeb Printing Michael Terry Al Corbeil x105 PRODUCTION [email protected] [email protected] PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT NO. -

Got Me Wrong

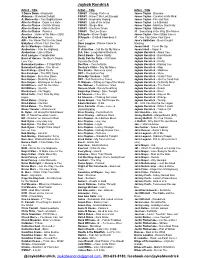

Jaykob Kendrick Artist - Title Artist - Title Artist - Title 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite CSN&Y - Change Partners James Taylor - Blossom Alabama – Dixieland Delight CSN&Y - Haven't We Lost Enough James Taylor - Carolina in My Mind A. Morissette – You Oughta Know CSN&Y - Helplessly Hoping James Taylor - Fire and Rain Alice in Chains - Down in a Hole CSN&Y - Lady of the Island James Taylor - Lo & Behold Alice in Chains - Got Me Wrong CSN&Y - Simple Man James Taylor - Machine Gun Kelly Alice in Chains - Man in the Box CSN&Y - Southern Cross James Taylor - Millworker Alice in Chains - Rooster CSN&Y - The Lee Shore JT - Something in the Way She Moves America – Horse w/ No Name ($20) D’Angelo – Brown Sugar James Taylor - Sweet Baby James Amy Winehouse – Valerie D’Angelo – Untitled (How does it JT - You Can Close Your Eyes AW – You Know That I’m No Good feel?) Jane's Addiction - Been Caught Babyface - When Can I See You Dave Loggins - Please Come to Stealing Arctic Monkeys - Arabella Boston Jason Isbell – Cover Me Up Audioslave - I Am the Highway D. Allan Coe - Call Me By My Name Jason Isbell – Super 8 Audioslave - Like a Stone D.A. Coe - Long-Haired Redneck Jaykob Kendrick - About You Avril Lavigne - Complicated David Bowie - Space Oddity Jaykob Kendrick - Barrelhouse Band of Horses - No One's Gonna Death Cab for Cutie – I’ll Follow Jaykob Kendrick - Fall Love You You into the Dark Jaykob Kendrick - Firefly Barenaked Ladies – If I had $1M Des’Ree – You Gotta Be Jaykob Kendrick - Kissing You Barenaked Ladies - One Week Destiny’s Child – Say My Name Jaykob Kendrick - Map Ben E King – Stand By Me Dire Straits - Romeo & Juliet Jaykob Kendrick - Medicine Ben Erickson - The BBQ Song DBT – Decoration Day Jaykob Kendrick - Muse Ben Harper - Burn One Down Drive-By Truckers - Outfit Jaykob Kendrick - Nuckin' Futs Ben Harper - Steal My Kisses DBT - Self-Destructive Zones Jaykob Kendrick – On the Good Foot Ben Harper - Waiting on an Angel D. -

2021 Breeze Show Choir Catalog

Previously Arranged Titles (updated 2/24/21) Specific details about each arrangement (including audio samples and cost) are available at https://breezetunes.com . The use of any of these arrangements requires a valid custom arrangement license purchased from https://tresonamusic.com . Their licensing fees typically range from $180 to $280 per song and must be paid before you can receive your music. Copyright approval frequently takes 4-6 weeks, sometimes longer, so plan accordingly. If changes to the arrangement are desired, there is an additional fee of $100. Examples of this include re-voicing (such as from SATB to another voice part), rewriting band parts, making cuts, adding an additional verse, etc. **Arrangements may be transposed into a different key free of charge, provided that the change does not make re-voicing necessary** For songs that do not have vocal rehearsal tracks, these can be created for $150/song. To place an order, send an e-mail to [email protected] or submit a license request on Tresona listing Garrett Breeze as the arranger, Tips for success using Previously Arranged Titles: • Most arrangements can be made to work in any voicing, so don’t be afraid to look at titles written for other combinations of voices than what you have. Most SATB songs, for example, can be easily reworked for SAT. • Remember that show function is one of the most important things to consider when purchasing an arrangement. For example, if something is labelled in the catalog as a Song 2/4, it is probably not going to work as a closer. -

Walk Off the Earths Första Sverigespelning Flyttar Till Debaser Medis

2014-01-28 15:24 CET Walk Off The Earths första Sverigespelning flyttar till Debaser Medis Biljetterna till Youtube-fenomenet Walk Off The Earths första Sverigespelning den 19 april 2014 har sålt så bra att konserten flyttas från Debaser Strand till Debaser Medis. Det kanadensiska bandet har gjort stor succé med sina kreativa covers på allt från Nirvana till Taylor Swift. De har över 1,6 miljoner prenumeranter på Youtube och deras största hit, covern på Gotyes “Somebody That I Used To Know”, har hela 156 miljoner visningar. I november uppträdde Walk Off The Earth på den stora galan Youtube Music Award inför över fyra miljoner tittare.Walk Off The Earth "Gang of Rhythm Tour” 2014 Lördag 19 april 2014 – Stockholm, Debaser Medis Biljetter Biljetterna köps via Debaser.se och Blixten.se och finns både från 18 och 20 år. Videor WOTEs turnéfilm: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tZ_YqyMmiCU&sns=em WOTEs cover på Gotyes "Somebody That I Used To Know”: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d9NF2edxy-M WOTEs cover på Taylor Swifts "I Knew You Were Trouble”: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WcM14Al83LsWalk Off The EarthWalk Off The Earth (WOTE) består av multimusikerna Gianni Luminati, Ryan Marshall och Sarah Blackwood, Mike Taylor på keyboards och Joel Cassady på trummor. De har blivit kända för sina kreativa Youtube-filmer som fått flera miljoner visningar – allt från en cover på tv-serien "Weeds” titellåt "Little Boxes” till Taylor Swifts "I Knew You Were Trouble”. Deras mest populära cover är Gotyes "Somebody That I Used To Know” där alla bandmedlemmar spelar på samma gitarr och som visats 156 miljoner gånger. -

Feat. the Silverlake Conservatory of Music Children's Choir

Name Name Artist Album Year Date Modified Lose Your Soul (feat. the Silverlake Dead Man's Bones (feat. The Silverlake 1 Dead Man's Bones 2009 1/1/2013 Conservatory of Music Children's Choir) Conservatory of Music Children's Choir) 2 Grillz (feat. Paul Wall, Ali & Gipp & Ali) Nelly, Paul Wall & Ali & Gipp 6 Pack - EP 2010 1/17/2013 3 Name The Goo Goo Dolls A Boy Named Goo 1995 1/19/2013 4 Don't Fear the Reaper Bobtown Trouble I Wrought 2012 1/20/2013 5 Wonder Why We Ever Go Home Jimmy Buffett 1977 1/25/2013 6 Trojans Atlas Genius Through the Glass - EP 2012 1/25/2013 7 Night Nurse Gregory Isaacs Night Nurse 1982 1/26/2013 8 Half Moon Blind Pilot We Are the Tide 2011 1/26/2013 9 Theme for Ernie John Coltrane The Very Best of John Coltrane 2012 1/30/2013 10 Nostalgia Emily Barker & The Red Clay Halo Fields of June - Single 2012 1/30/2013 11 Bandages Hey Rosetta! Seeds 2012 1/31/2013 12 Atlantic City The Band Jericho 1993 2/2/2013 13 Glory Box John Martyn The Church With One Bell 1998 2/2/2013 14 The Messiah Will Come Again Roy Buchanan Sweet Dreams: The Anthology 1992 2/2/2013 15 Overjoyed Matchbox Twenty North (Deluxe Version) 2012 2/2/2013 16 Walls Lisa Loeb No Fairy Tale (Bonus Track Version) 2013 2/3/2013 17 Feel So Close Calvin Harris You Tube 2013 2/4/2013 18 Free Graffiti6 You Tube 2013 2/4/2013 19 Sex on Fire King of Leon You Tube 2013 2/4/2013 20 Breathe Me Sia You Tube 2013 2/4/2013 21 Sweet Surrender Sarah McLachlan You Tube 2013 2/4/2013 22 Kind and Generous (iTunes Session) Natalie Merchant iTunes Session 2011 2/6/2013 23 Suite: -

Manuary: Food Drive for Men Model UN Takes UPENN What Happened

In this edition: Senior Poll Results, New Bands, Sports The Harborview Updates, and More! Volume 50 Edition 4 Cold Spring Harbor High School January 2012 Manuary: Food Drive For Men Model UN Takes UPENN By Christina Carmi and tion, such as the ‘eye roll’ and the Stephanie Mahder ‘stare down’, which left many com- At this year’s 28th annual petitors quivering in their shoes. Model UN conference in Phila- Our eighteen delegates each add- delphia, Pennsylvania, delegates ed unique points that contributed from our own school represented to the resolutions in their com- the countries of Israel and Sa- mittees. Model UN is a club that moa. ILMUNC (Ivy League Model requires each member to put in United Nations Conference) is extra time for researching the top- hosted by the University of Penn- ics at hand, and every member of sylvania’s own Model UN mem- our club proved prepared. Each bers, including the beautiful Alice delegate spent weeks researching Kissilenko, one of the head chairs and studying their topics, specifi- at the conference. The four-day cally from their country’s perspec- long conference brings delegates tive. The event isn’t only a way to from all over the world to rep- learn more about world relations, By Stephanie Mahder raiser called “Manuary”. This fun- each teacher shaved designs in resent a plethora of nations and although it definitely teaches you Especially during the draiser has gotten students and their beard for the final week resolve a variety of different prob- about things that you might not weeks surrounding Thanksgiv- teachers within the high school of the competition.