Arguing Through Writing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

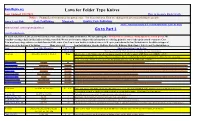

Laws for Folder Type Knives Go to Part 1

KnifeRights.org Laws for Folder Type Knives Last Updated 1/12/2021 How to measure blade length. Notice: Finding Local Ordinances has gotten easier. Try these four sites. They are adding local government listing frequently. Amer. Legal Pub. Code Publlishing Municode Quality Code Publishing AKTI American Knife & Tool Institute Knife Laws by State Admins E-Mail: [email protected] Go to Part 1 https://handgunlaw.us In many states Knife Laws are not well defined. Some states say very little about knives. We have put together information on carrying a folding type knife in your pocket. We consider carrying a knife in this fashion as being concealed. We are not attorneys and post this information as a starting point for you to take up the search even more. Case Law may have a huge influence on knife laws in all the states. Case Law is even harder to find references to. It up to you to know the law. Definitions for the different types of knives are at the bottom of the listing. Many states still ban Switchblades, Gravity, Ballistic, Butterfly, Balisong, Dirk, Gimlet, Stiletto and Toothpick Knives. State Law Title/Chapt/Sec Legal Yes/No Short description from the law. Folder/Length Wording edited to fit. Click on state or city name for more information Montana 45-8-316, 45-8-317, 45-8-3 None Effective Oct. 1, 2017 Knife concealed no longer considered a deadly weapon per MT Statue as per HB251 (2017) Local governments may not enact or enforce an ordinance, rule, or regulation that restricts or prohibits the ownership, use, possession or sale of any type of knife that is not specifically prohibited by state law. -

Scraps of Hope in Banda Aceh

Marjaana Jauhola Marjaana craps of Hope in Banda Aceh examines the rebuilding of the city Marjaana Jauhola of Banda Aceh in Indonesia in the aftermath of the celebrated SHelsinki-based peace mediation process, thirty years of armed conflict, and the tsunami. Offering a critical contribution to the study of post-conflict politics, the book includes 14 documentary videos Scraps of Hope reflecting individuals’ experiences on rebuilding the city and following the everyday lives of people in Banda Aceh. Scraps of Hope in Banda Aceh Banda in Hope of Scraps in Banda Aceh Marjaana Jauhola mirrors the peace-making process from the perspective of the ‘outcast’ and invisible, challenging the selective narrative and ideals of the peace as a success story. Jauhola provides Gendered Urban Politics alternative ways to reflect the peace dialogue using ethnographic and in the Aceh Peace Process film documentarist storytelling. Scraps of Hope in Banda Aceh tells a story of layered exiles and displacement, revealing hidden narratives of violence and grief while exposing struggles over gendered expectations of being good and respectable women and men. It brings to light the multiple ways of arranging lives and forming caring relationships outside the normative notions of nuclear family and home, and offers insights into the relations of power and violence that are embedded in the peace. Marjaana Jauhola is senior lecturer and head of discipline of Global Development Studies at the University of Helsinki. Her research focuses on co-creative research methodologies, urban and visual ethnography with an eye on feminisms, as well as global politics of conflict and disaster recovery in South and Southeast Asia. -

Fine Art & Antiques Auction

FINE ART & ANTIQUES AUCTION Tuesday 26th ofMarch Bath Ltd2019. at 10.00am Lot: 138 AT PHOENIX HOUSE Lower Bristol Road, BATH BA2 9ES Tel: (01225) 462830 Aldr-CatCover.qxp:Aldr-CatCover07 20/3/12 15:33 Page 2 Aldr-CatCover.qxp:Aldr-CatCover07 20/3/12 15:33 Page 2 BUYER’S PREMIUM AAB Buyer’suyer’s p premiumremium o off 1 20%7B.U5%Y ofEo fRthet’hSe hammerPhRamEmMeI rUpricepMrice isi spayablepayable ata tallal lsales.sales. A ThisTBhuiyse premiumpr’rsepmreiummiu iisms subjectsoufb1je7c.t5 %ttoo othethf et hadditionaeddhiatmiomn eoforf pVATVrAiTce ataits thetphaey standardsatbalnedaatrdal rate.lrastael.es. This premium is subject to the addition of VAT at the standard rate. CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. Every effort has been madCeOtoNeDnsIuTrIeOthNe SacOcuFraScyAoLfEthe description of each lot but 1. Ethveesrey wefhfoertthherasmbaedeen omraaldlye toor einstuhre tchaetaaloccgureacayreoefxtphreesdseioscnrsipotifoonpoinf ieoanchanlodt nbuot trhepersesewnhtaetihoenrsmoafdfeacot.raNlloy eomr pinloythee ocafttahloegAuuecatiroeneexeprsrehssaisonans yofauotphinorioitny taondmnakoet arenpyrerseepnrteasteinotnastiofnfoafctf.acNtoanemd pthloeyaeuecotifotnheeerAs udcitsicolaniemersonhabsehanalyf oauf tthhoerViteyntdoomr aankde athneymreseplrveessenretsaptioonnsiobfilfiatyctfoanr dautthheenautictiitoy,naegeers, odriisgcilnaimandoncobnedhiatlifonofatnhde fVoernadcocur raancdy othfemmesaesluvreesmreesnptoonrsiwbieligtyhtfoorfaauntyhelonttiocritlyo,tasg. e, origin and condition and for accuracy oPfumrcehaassuerresmpeunrtcohrasweeiaglhl tlootfsavniyewloetdorwliotths. -

Rosary Hill Reach out Part II: Community Action Corps

Rosary Hill Reach Out Part II: Community Action Corps by MARIE FORTUNA “You can’t explain wheel-chair Dr. John Starkey nodded about all kinds of human prob strengths to help others, the at the Veteran’s Administration dancing. You’d have to see it. understandingly. “As a kind of lems. Kept the whole class talk world would be a happier place.” Hospital seeks students to feed Thursday afternoons the patients middleman between volunteers ing on that record for the total patients, visit them, lead a com themselves create the dances. and agencies they serve, I ’ve class period,” said sophomore Brian McQueen practice munity sing-a-long,” 'said Dr. Tuesdays they teach it to us. To seen how students have started Bri^n McQueen. teaches at Heim Elementary. Starkey. Angela Kell«*, Virginia Ventura, out frightened of what they don’t He’s busy. Pat Weichsel resident Pat Cowles, Linda Stone and know,” he said. ‘«‘Once they try Brian teaches C.C.D. classes to assistant, volunteer for Project Erie County Detention Home me,” said Pat Weichsel, student it,” he continued, “they find they about 18 seventh graders at Care (as a requirement for her looks for companions and helpers coordinator of the Campus are rewarded.” Saints Peter and Paul School in community psychology course) with the recreation programs for Ministry sponsored Community Williamsville. He has been help says, “Tim eis more of a problem boys $nd girls age 8 to 16 years Action Corps. - “Working for the first time ing children since he himself was than anything else. I don’t really who are awaiting court proceed with persons who have physical 14 years old. -

Nobody Expects the Spanish Inquisition

Nobody Expects the Spanish Inquisition Nobody Expects the Spanish Inquisition Cultural Contexts in Monty Python Edited by Tomasz Dobrogoszcz Foreword by Terry Jones ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com 16 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BT, United Kingdom Copyright © 2014 by Rowman & Littlefield All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition : cultural contexts in Monty Python / edited by Tomasz Dobrogoszcz ; foreword by Terry Jones. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-3736-0 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-3737-7 (ebook) 1. Monty Python (Comedy troupe) I. Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, 1970– editor. PN2599.5.T54N63 2014 791.45'028'0922–dc23 2014014377 TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America But remember, if you’ve enjoyed reading this book just half as much as we’ve enjoyed writing it, then we’ve enjoyed it twice as much as you. Contents Acknowledgments ix Foreword xi Part I: Monty Python’s Body and Death 1 1 “It’s a Mr. -

Social Mania: the Impact of Likes, Posts, and Swipes on Insurance Never Before Has Such a Small Number of Companies Held Such Influence

Social Mania: The Impact of Likes, Posts, and Swipes on Insurance Never before has such a small number of companies held such influence. Silicon Valley’s social media giants connect, inform, anger, and interest billions of people. How can we assess the impact of all those likes, posts, and swipes on the South Africa Neil Parkin Chief Pricing Actuary insurance markets? RGA explores the power, and peril, of several social trends: RGA South Africa Employee Social Endorsement In a Weber Shandwick/KRC Research global survey of 2,300 employees at mid-sized or Cliff Jooste Chief Underwriter larger companies, 50% said they post messages, pictures, or videos about an employer RGA South Africa often or from time-to-time. On the positive side, much of that content involves industry insights that can burnish Belinda Thorpe brand reputation, or workplace posts that can help recruit and retain associates. Research Head of Claims Africa and Middle East demonstrates that commentary and advice from employee experts is far more likely to RGA South Africa be considered authentic and trustworthy within social networks than similar posts from a faceless corporation. In the same survey, 39% of employees shared praise or positive comments online about an employer. Yet social media also presents risks: 16% of respondents in the survey reported sharing criticism or negative comments online and 14% said they posted something in social media about an employer that they regretted. A poorly considered post can generate public backlash and unwanted viral conversations. Furthermore, unauthorized and accidental disclosures of personal and confidential information can also be used in cybersecurity attacks. -

And Now for Something Completely Different …

And Now for Something Completely Different … This week I was talking to a prospect in the marketing department of a company that I had been introduced to by a colleague. They are in the storage industry and are looking to make a big splash by flooding their “message” out to end users, resellers, and analysts. I was told that they had a very well developed content stable so they may not need the full range of DCIG services but that introducing my company to them could prove beneficial. The ensuing conversation reminded very much me of one of my favorite Monty Python’s Flying Circus show sketches; The Cheese Shop sketch. (Cue the Bouzouki music) Me: So you are trying to get the message out into the hands of end users looking to make a buying decision right? So you probably have some Case Studies to share with them? Prospect: No, not today. Me: Ok, then do you have any White papers that you are able to put into the hands of their hands so that they can look at your technical benefits in a detailed manner? Prospect: Afraid we are fresh out. Me: Webinars? Prospect: No Me: Executive white papers? Prospect: No Me: Product Evaluations Prospect: We had one coming, but the truck broke down. Me: How about blogs? Certainly you must have blogs? Prospect: No Me: Product spec sheets? Prospect: Oh yes…! We have those. Me: Super, we can derive content from them and a briefing with your team, can we get some of them to start with? Prospect: Well, they are kind of runny… Me: Oh that’s OK, we like them runny! We can tighten them up for you and deliver them in a way that resonates with your prospective clients. -

We Want More

GOT ISSUES 1 For laid back lifestylers... with a sense of humour 2017 WE WANT MORE Festivals are in a constant state of A half-century later, it’s not just bellbottoms and wanderlust and desire for unique and memory-making evolution, there are now literally hundreds marijuana anymore. Music festivals have evolved into moments – the world is now literally your glittering, of them all over the country and they have a booming multimillion-pound business. But why is it flower-crown-filled oyster! It seems many of us no that so many of us time and time again clear an entire longer have the ‘Woodstock mentality’ and are not up gone from just being a place where you weekend to spend it camping in a foreign town with for pitching our dodgy tents in the rain to hear our watch bands in a field, to an entire four thousands of strangers? favourite band and roughing it anymore, so what do day immersive experience. we want from our festivals? We are craving and chasing experiences over It has been 47 years since Generation X dressed in belongings more than ever before and what better suede hippie vests and flower crowns and gathered at place than in a fairytale haze of escapism in the the firstPilton Pop, Blues & Folk Festival (now more middle of the British countryside…or further afield if commonly known as one of the best festivals in the you really want to live out those hedonistic dreams. world –Glastonbury!), for 1 night of music and peace. Festivals are having to work harder to satisfy our Single-eState gift S S traight from the farmer | cha S ediS tillery.co.uk 2 2017 2017 3 What’s cookin One thing we do know is that festi- joy of spontaneity and is both designed and built by 60 Seconds food is fast becoming just as central teams of emerging artists, architects and musicians; all good lookin’ to the experience as the music. -

Monty Python's Completely Useless Web Site

Home Get Files From: ● MP's Flying Circus ● Completely Diff. ● Holy Grail ● Life of Brian ● Hollywood Bowl ● Meaning of Life General Information | Monty Python's Flying Circus | Monty Python and the Holy Grail | Monty Python's Life of Brian | Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl | Monty Python's The Meaning of Life | Monty Python's Songs | Monty Python's Albums | Monty Python's ...or jump right to: Books ● Pictures ● Sounds ● Video General Information ● Scripts ● The Monty Python FAQ (25 Kb) Other stuff: ● Monty Python Store ● Forums RETURN TO TOP ● About Monty Python's Flying Circus Search Now: ● Episode Guide (18 Kb) ● The Man Who Speaks In Anagrams ● The Architects ● Argument Sketch ● Banter Sketch ● Bicycle Repair Man ● Buying a Bed ● Blackmail ● Dead Bishop ● The Man With Three Buttocks ● Burying The Cat ● The Cheese Shoppe ● Interview With Sir Edward Ross ● The Cycling Tour (42 Kb) ● Dennis Moore ● The Hairdressers' Ascent up Mount Everest ● Self-defense Against Fresh Fruit ● The Hospital ● Johann Gambolputty... ● The Lumberjack Song [SONG] ● The North Minehead Bye-Election ● The Money Programme ● The Money Song [SONG] ● The News For Parrots ● Penguin On The Television ● The Hungarian Phrasebook ● Flying Sheep ● The Pet Shop ● The Tale Of The Piranha Brothers (10 Kb) ● String ● A Pet Shop Near Melton Mowbray ● The Trail ● Arthur 'Two Sheds' Jackson ● The Woody Sketch ● 1972 German Special (42 Kb) RETURN TO TOP Monty Python and the Holy Grail ● Complete Script Version 1 (74 Kb) ● Complete Script Version 2 (195 Kb) ● The Album Of -

NADS News — March, 2016 1 Contents World Down Syndrome Day

Owen Paris and his dad Mike NewsletterNADS for the National Association for Down SyndromeNews March, 2016 The PAC Self-Advocacy Workshop Sarah Weinstein wo weeks ago I attended the accomplishments, our jobs, hobbies up were: opportunities to share our NADS PAC (Partnership Advocacy and enthusiasm for learning new hardships and struggles with healthy Council)T Self-Advocacy Workshop things. (I think our parents had fun choices and peer pressure, telling at Elmhurst College with 21 other talking with each other too. They were other people how to help us when our aspiring self-advocates. We practiced invited either to stay and listen to the feelings are hurt or we see someone skills and techniques to help us be workshop or to hang out and network mistreated or bullied and finding confident in telling other people about programs and services around ways to let others know we want more about our preferences, our skills, the Chicago suburban area.) opportunities to help out and work by interests and our goals and dreams. It Janice Weinstein, Executive Director sharing our talents and gifts. There was so much fun to get to know other of Total Link2 Community, helped us were so many talented people in the adults with Down syndrome. Everyone get comfortable with one another room and we took the time to hear was excited to share their proud using improv and drama games. You each person’s voice. We also had a lot could feel the energy level go up to say about what we’re good at and when Janice asked us to stand in a how we want other people to view us circle facing one another. -

NEW FRIENDS and OLD PASSIONS WELLNESS and HOME CARE Table of Contents

MessengerVolume 100, Issue 1 | Spring 2019 The Meaning of Happiness NEW FRIENDS AND OLD PASSIONS WELLNESS AND HOME CARE Table of Contents PHOEBE AT WORK 4 A Place Regenerated 28 Philanthropy: High Marks for Highmark 31 Phoebe Pharmacy: Person-Centered Technology THE ART OF LIVING 8 Finding “Happy” 4 16 A Lifetime of Music 20 Friendship Across Phoebe THE GREATEST GENERATION 26 The Soldier with a Green Thumb HEALTH & WELLNESS 12 Pathstones by Phoebe: The Path to Wellness 14 Ask the Expert: Getting to Know Home Care HAPPENINGS 30 The Phoebe Institute on Aging: Sanity & Grace 20 16 Phoebe-Devitt Homes is the official name of the 501(c)(3) not-for-profit corporation doing business as Phoebe Ministries. Founded in 1903 and incorporated as such in 1984, Phoebe-Devitt Homes is responsible for the supervision of communities, long-range planning, development, and fundraising for a network of retirement and affordable housing communities, pharmacies, and a continuing care at home program, which combined serve thousands of seniors annually. Phoebe Ministries is affiliated with the United Church of Christ and is a member of LeadingAge, LeadingAge PA, and the Council for Health and Human Service Ministries of the United Church of Christ. The official registration and financial information of Phoebe-Devitt Homes may be obtained from the Pennsylvania Department of State by calling toll free within Pennsylvania at 1-800-732-0999. Registration does not imply Generations come together: On the cover: endorsement. Bob Masenheimer, Phoebe Berks, conducts Copyright 2019 by Phoebe Ministries. Photographs and artwork copyright by rehearsal for the Phoebe Institute on Aging their respective creators or Phoebe Ministries. -

The Parthenon, March 11, 2013

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar The aP rthenon University Archives 3-11-2013 The aP rthenon, March 11, 2013 John Gibb [email protected] Tyler Kes [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon Recommended Citation Gibb, John and Kes, Tyler, "The aP rthenon, March 11, 2013" (2013). The Parthenon. Paper 197. http://mds.marshall.edu/parthenon/197 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aP rthenon by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. C M Y K 50 INCH Higher Learning Tour takes Huntington to school > more on News Monday, MARCH 11, 2013 | VOL. 116 NO. 100 | MARSHALL UNIVERSITY’S STUDENT NEWSPAPER | marshallparthenon.com Get to know your candidates SUBMITTED PHOTOS THE PARTHENON’S KIM SMITH SPOKE WITH THE THREE PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES BEFORE THE Platform Agendas UPCOMING ELECTIONS TO FIND OUT EXACTLY WHICH ISSUES ARE IMPORTANT. Derek Ramsey & Sarah Stiles EJ Hassan & Ashley Lyons Wittlee Retton & Dustin Murphy • We want to promote to students on cam- • Establish open forum to engage student body • Things for the average students are discount pus, show what they are doing. with Student Government Executive Branch. cards especially for Student Organizations. • We want to help get your organization • Partner SGA up with Greek Affairs and other • We have the idea of suggestion boxes that service oriented groups to host a day on campus will be placed all around campus.