Romanization Through Mosaics: Transition at Fishbourne and Colchester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fishbourne: a Roman Palace and Its Garden, 1971, Barry W. Cunliffe, 0801812666, 9780801812668, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971

Fishbourne: A Roman Palace and Its Garden, 1971, Barry W. Cunliffe, 0801812666, 9780801812668, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1O80BJ2 http://goo.gl/Rblvo http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fishbourne_A_Roman_Palace_and_Its_Garden DOWNLOAD http://goo.gl/R4Dxp http://bit.ly/W9p35D The Roman Villa in Britain , Albert Lionel Frederick Rivet, 1969, Pavements, Mosaic, 299 pages. Excavations at Fishbourne, 1961-1969, Issue 26, Volume 1 , Barry W. Cunliffe, 1971, History, 221 pages. Facing the Ocean The Atlantic and Its Peoples, 8000 BC-AD 1500, Barry W. Cunliffe, Jan 1, 2001, History, 600 pages. An illustrated history of the peoples of "the Atlantic rim" explores the inter- relatedness of European cultures that stretched from Iceland to Gibralter.. The Romans at Ribchester discovery and excavation, B. J. N. Edwards, University of Lancaster. Centre for North-West Regional Studies, Jan 1, 2000, History, 101 pages. Germania , Cornelius Tacitus, 1970, History, 175 pages. Offers a portrait of Julius Agricola - the governor of Roman Britain and Tacitus' father-in-law - and an account of Britain that has come down to us. This book provides. The Recent Discoveries of Roman Remains Found in Repairing the North Wall of the City of Chester (A Series of Papers Read Before the Chester Archaeological and Historic Society, Etc., and Reprinted by Permission of the Council.) Extensively Illustrated, John Parsons Earwaker, 1888, Romans, 175 pages. Roman Canterbury, as so far revealed by the work of the Canterbury Excavation Committee , Canterbury Excavation Committee, 1949, History, 16 pages. Roman Silchester the archaeology of a Romano-British town, George C. Boon, 1957, Silchester (England), 245 pages. -

RULES of PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety

The Fall of Roman Britain RULES OF PLAY COIN Series, Volume VIII by Marc Gouyon-Rety T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S 1.0 Introduction ............................2 6.0 Epoch Rounds .........................18 2.0 Sequence of Play ........................6 7.0 Victory ...............................20 3.0 Commands .............................7 8.0 Non-Players ...........................21 4.0 Feats .................................14 Key Terms Index ...........................35 5.0 Events ................................17 Setup and Scenarios.. 37 © 2017 GMT Games LLC • P.O. Box 1308, Hanford, CA 93232 • www.GMTGames.com 2 Pendragon ~ Rules of Play • 58 Stronghold “castles” (10 red [Forts], 15 light blue [Towns], 15 medium blue [Hillforts], 6 green [Scotti Settlements], 12 black [Saxon Settlements]) (1.4) • Eight Faction round cylinders (2 red, 2 blue, 2 green, 2 black; 1.8, 2.2) • 12 pawns (1 red, 1 blue, 6 white, 4 gray; 1.9, 3.1.1) 1.0 Introduction • A sheet of markers • Four Faction player aid foldouts (3.0. 4.0, 7.0) Pendragon is a board game about the fall of the Roman Diocese • Two Epoch and Battles sheets (2.0, 3.6, 6.0) of Britain, from the first large-scale raids of Irish, Pict, and Saxon raiders to the establishment of successor kingdoms, both • A Non-Player Guidelines Summary and Battle Tactics sheet Celtic and Germanic. It adapts GMT Games’ “COIN Series” (8.1-.4, 8.4.2) game system about asymmetrical conflicts to depict the political, • A Non-Player Event Instructions foldout (8.2.1) military, religious, and economic affairs of 5th Century Britain. -

THE PARISHES of St Peter and St Mary, New Fishbourne, and St Mary the Virgin, Apuldram Rector: the Reverend Canon Moira Wickens

THE PARISHES OF St Peter and St Mary, New Fishbourne, and St Mary the Virgin, Apuldram Rector: The Reverend Canon Moira Wickens We Will Remember Them On the eleventh day of this eleventh month there will be special services in both our churches, to mark the 100th anniversary of the ending of the first world war. We will be joining our prayers and thoughts with countless others across the world, and you are invited to join us. At 8.00am there will be a short service at St. Mary's Church Apuldram, and then at 10.30am at Fishbourne, with the act of Remembrance taking place at the eleventh hour. If you pop into either of the churches you will see the 'silent soldiers', almost invisible figures representing those from our parishes who gave their lives for our freedom. These figures may unnerve you, for they are there, but not there, and yet they remind us all not only of those who served our country during the great wars, but also those who have been in conflicts since. We will remember those who serve in the armed forces to this day, and all those who have survived. We will also remember the great acts of service that were carried out by so many women who not only supported the men, but who also kept our country going during those terrible years. During both our services we will listen to special readings, 'The Soldier', and 'Flanders Fields', wreathes will be laid, and the names of the men from our communities who are on the memorial plaques inside the churches, will be read out. -

ARTHUR of CAMELOT and ATHTHE-DOMAROS of CAMULODUNUM: a STRATIGRAPHY-BASED EQUATION PROVIDING a NEW CHRONOLOGY for 1St MIILLENNIUM ENGLAND

1 Gunnar Heinsohn (15 June 2017) ARTHUR OF CAMELOT AND ATHTHE-DOMAROS OF CAMULODUNUM: A STRATIGRAPHY-BASED EQUATION PROVIDING A NEW CHRONOLOGY FOR 1st MIILLENNIUM ENGLAND “It seems probable that Camelot, Chrétien de Troyes’ [c. 1140-1190 AD] name for Arthur's Court, is derived directly from Camelod-unum, the name of Roman Colchester. The East Coast town was probably well-known to this French poet, though whether he knew of any specific associations with Arthur is unclear. […] John Morris [1973] suggests that Camulodunum might actually have been the High-King Arthur's Eastern Capital” (David Nash Ford 2000). "I think we can dispose of him [Arthur] quite briefly. He owes his place in our history books to a 'no smoke without fire' school of thought. [...] The fact of the matter is that there is no historical evidence about Arthur; we must reject him from our histories and, above all, from the titles of our books" (David N. Dumville 1977, 187 f.) I Why neither the habitats of Arthurian Celts nor the cities of their Saxon foes can be found in post-Roman Britain p. 2 II Contemporaneity of Saxons, Celts and Romans during the conquest of Britain in the Late Latène period of Aththe[Aθθe]-Domaros of Camulodunum/Colchester p. 14 III Summary p. 29 IV Bibliography p. 30 Author’s1 address p. 32 1 Thanks for editorial assistance go to Clark WHELTON (New York). 2 I Why neither the habitats of Arthurian Celts nor the cities of their Saxon foes can be found in post-Roman Britain “There is absolutely no justification for believing there to have been a historical figure of the fifth or sixth century named Arthur who is the basis for all later legends. -

Ii. Sites in Britain

II. SITES IN BRITAIN Adel, 147 Brough-by-Bainbridge, 32 Alcester, cat. #459 Brough-on-Noe (Navia), cat. #246, Aldborough, 20 n.36 317, 540 Antonine Wall, 20 n.36, 21, 71, 160, 161 Brough-under-Stainmore, 195 Auchendavy, I 61, cat. #46, 225, 283, Burgh-by-Sands (Aballava), 100 n.4, 301, 370 118, 164 n.32, cat. #215, 216, 315, 565-568 Backworth, 61 n.252, 148 Burgh Castle, 164 n.32 Bakewell, cat. #605 Balmuildy, cat. #85, 284 Cadder, cat. #371 Bar Hill, cat. #296, 369, 467 Caerhun, 42 Barkway, 36, 165, cat. #372, 473, 603 Caerleon (lsca), 20 n.36, 30, 31, 51 Bath (Aquae Sulis), 20, 50, 54 n.210, n.199, 61 n.253, 67, 68, 86, 123, 99, 142, 143, 147, 149, 150, 151, 128, 129, 164 n.34, 166 n.40, 192, 157 n.81, 161, 166-171, 188, 192, 196, cat. #24, 60, 61, 93, 113, I 14, 201, 206, 213, cat. #38, 106, 470, 297, 319, 327, 393, 417 526-533 Caernarvon (Segontium), 42 n.15 7, Benwell (Condercum), 20 n.36, 39, 78, 87-88, 96 n.175, 180, 205, 42 n.157, 61, 101, 111-112, 113, cat. #229 121, 107 n.41, 153, 166 n.40, 206, Caerwent (Venta Silurum), 143, 154, cat. #36, 102, 237, 266, 267, 318, 198 n. 72, cat. #469, 61 7 404, 536, 537, 644, 645 Canterbury, 181, 198 n.72 Bertha, cat. #5 7 Cappuck, cat. #221 Bewcastle (Fan um Cocidi), 39, 61, I 08, Carley Hill Quarry, 162 111 n.48, 112, 117, 121, 162, 206, Carlisle (Luguvalium), 43, 46, 96, 112, cat. -

Boundary Commission England Recommendations for Review of Wards of Chichester District Council

BOUNDARY COMMISSION ENGLAND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REVIEW OF WARDS OF CHICHESTER DISTRICT COUNCIL Response from FISHBOURNE PARISH COUNCIL on the Boundary Commission’s three main considerations. 1. Electoral Equality achieved by Draft recommendations: Boundary Commission Recommendation: Bosham, Fishbourne, Appledram and Donnington to form a 3 member ward entitled Bosham & Donnington Ward. Electorate Electors per Variance Electorate Electors per Variance (2015) Councillor from (2021) Councillor from (2015) average (2021) average 7,924 2,641 3% 8,355 2,785 1% COMMENT: The proposal meets the consideration of improving electoral equality. 2. Reflection of Community Identity. COMMENT: There is serious concern about the unintended damage that would be caused by the choice of name for the new ward. Though “Bosham and Donnington” has the advantage of marking the geographical extremes of the new ward, it omits two of the village names and this could have damaging (though unintended) outcomes. Whatever rule is applied to naming of new wards has to have room for some flexibility. This is where local knowledge has such an important part to play. In this particular case, combining the names of four separate villages under the name of two of them conflicts both with the Fishbourne Neighbourhood Plan and with the CDC's own local plan both of which stress the need for the preservation of the individual villages and of the neighbouring AONB. This is vital not only because of the quality of life in the separate villages but also because we are fighting to prevent major developers from building on the strategic gaps between villages and destroying for ever the charm and attraction of the coastal villages and their popularity as a tourist area. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A study of the client kings in the early Roman period Everatt, J. D. How to cite: Everatt, J. D. (1972) A study of the client kings in the early Roman period, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10140/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk .UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM Department of Classics .A STUDY OF THE CLIENT KINSS IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE J_. D. EVERATT M.A. Thesis, 1972. M.A. Thesis Abstract. J. D. Everatt, B.A. Hatfield College. A Study of the Client Kings in the early Roman Empire When the city-state of Rome began to exert her influence throughout the Mediterranean, the ruling classes developed friendships and alliances with the rulers of the various kingdoms with whom contact was made. -

Human Rights, Social Welfare, and Greek Philosophy Legitimate

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: H Interdisciplinary Volume 15 Issue 8 Version 1.0 Year 2015 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Human Rights, Social Welfare, and Greek Philosophy Legitimate Reasons for the Invasion of Britain by Claudius By Tomoyo Takahashi University of California, United States Abstract- In 43 AD, the fourth emperor of Imperial Rome, Tiberius Claudius Drusus, organized his military and invaded Britain. The purpose of this paper is to investigate the legitimate reasons for The Invasion of Britain led by Claudius. Before the invasion, his had an unfortunate life. He was physically distorted, so no one gave him an official position. However, one day, something unimaginable happened. He found himself selected by the Praetorian Guard to be the new emperor of Roma. Many scholars generally agree Claudius was eager to overcome his physical disabilities and low expectations to secure his position as new Emperor in Rome by military success in Britain. Although his personal motivation was understandable, it was not sufficient enough for Imperial Rome to legitimize the invasion of Britain. It is important to separate personal reasons and official reasons. Keywords: (1) roman, (2) britain, (3) claudius, (4) roman emperor, (5) colonies, (6) slavery, (7) colchester, (8) veterans, (9) legitimacy. GJHSS-H Classification: FOR Code: 180114 HumanRightsSocialWelfareandGreekPhilosophyLegitimateReasonsfortheInvasionofBritainbyClaudius Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2015. Tomoyo Takahashi. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Suburani Book 1 Overview

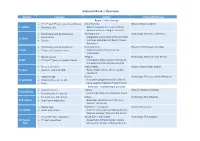

Suburani Book 1 Overview Chapter Language Culture History/Mythology Roma – life in the city • 1st, 2nd and 3rd pers. sg., present tense Life in the city History: Rome in AD 64 1: Subūrai • Reading Latin Subura; Population of city of Rome; Women at work; Living in an insula • Nominative and accusative sg. Building Rome Mythology: Romulus and Remus • Declensions Geography and growth of Rome; Public 2: Rōma • Gender buildings and spaces of Rome; Forum Romanum • Nominative and accusative pl. Entertainment History: Three phases of ruling 3: lūdī • 3rd pers. pl., present tense Public festivals; Chariot-racing; Charioteers • Neuter nouns Religion Mythology: Deucalion and Pyrrha 4: deī • 1st and 2nd pers. pl., present tense Christianity; State religion; Homes of the gods; Sacrifice; Private worship • Present infinitive Public health History: Rome under attack! 5: aqua • possum, volō and nōlō Baths; Public toilets; Water supply; Sanitation • Ablative case Slavery Mythology: Theseus and the Minotaur 6: servitium • Prepositions + acc./+ abl. How were people enslaved? Life of a • Time slave; Seeking freedom; Manumission Britannia – establishing a province • Imperfect tense London History: Romans invading 7: Londīnium • Perfect tense (-v- stems) Londinium; Made in Londinium; Food • Perfect tense (all stems) Britain Mythology: The Amazons 8: Britannia • Superlative adjectives Britannia; Camulodunum; Resist or accept? The Druids • Dative case Rebellion – hard power History: Resistance 9: rebelliō • Verbs with dative Chain of command; Competing forces; Women and war; Why join the army? • 1st and 2nd decl. adjectives Aquae Sulis – soft power Mythology: The Gorgons 10: Aquae • 3rd decl. adjectives Aquae Sulis; Different gods; Curses; Sūlis Military life; People of Roman Britain Gaul and Lusitania – life in a province • Genitive case The sea History: Pirates in the Mediterranean Sea • -ne and -que Romans and the sea; Underwater 11: mare archaeology; Navigation and maps; Dangers at sea • Imperatives (inc. -

The Battle of Watling Street Took Place in Roman-Occupied Britain in AD 60 Or

THE BATTLE OF WATLING STREET Margaret McGoverne First published in Great Britain in 2017 by Bright Shine Press Brightshinepress.com Copyright © Margaret McGoverne 2017 The right of Margaret McGoverne to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. For my boy, remembering our drives along the Icknield Way Contents Map of Roman Britain Principal Characters Place Names in Roman Britain Acknowledgements Background Part I Part II Part III Part IV Part V Epilogue Extract from The Bondage of The Soil Map of Roman Britain Principal Characters Dedo A young attendant of Queen Boudicca Boudicca Queen of the Iceni tribe, widow of King Prasutagus Brigomall A noble of the Iceni tribe, advisor to the queen Cata A young maiden in Boudicca’s travelling bodyguard Dias An elder of the village of Puddlehill Nemeta Younger daughter of Boudicca and Prasutagus Prasutagus King of the Iceni tribe, lately deceased Vassinus A young serving lad and friend of Dedo Mallo A mule owned by Dedo Place Names in Roman Britain Albion England Cambria Wales Camulodunum Colchester Durocobrivis Dunstable Hibernia Ireland Lactodurum Towcester Londinium London Magiovinium Fenny Stratford Venta Caistor St Edmund, Suffolk Icenorum Verlamion The Catuvellauni capital Verulamium Saint Albans (formerly Verlamion) Viroconium Wroxeter Cornoviorum Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to a number of people, although this list is by no means exhaustive. -

The Campaign of Aulus Plautius

Archaeological Journal ISSN: 0066-5983 (Print) 2373-2288 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raij20 The Campaign of Aulus Plautius Edwin Guest LL.D. To cite this article: Edwin Guest LL.D. (1866) The Campaign of Aulus Plautius, Archaeological Journal, 23:1, 159-180, DOI: 10.1080/00665983.1866.10851344 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00665983.1866.10851344 Published online: 11 Jul 2014. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 1 View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=raij20 Download by: [University of California, San Diego] Date: 29 June 2016, At: 13:17 CAMPAIGN OF AULUS PLAUTIUS. CAMBORITVM Η(ύιιιώτ·ιώ/ι^ ^MV^ODVNVM 7 'GLEVVM; tpZUrn^&ldicstcr ^Aylesbury \VER0LAMl VN! \KSPAlbans fandiim Abinadom >VLL0NIAC£ MoiJafortL iiibiimjioiHiiotif LONDIN WaiiiuraCPwll' Thames ν— ί or,Forest \ή*όmines Teddawto'V VERLVCIO "2 Sum ihpltifonLj' ^XlGiujstoiv iRIWEi Fu.i'ojjibe Wood <Si Gcarg es HilL· '•'ppily Wood ilu'ltf Wood. (mUdJbrcL W Downloaded by [University of California, San Diego] at 13:17 29 June 2016 DorlaJig PORTVSfiVBs J Se-CCARVM PORTVS/LEFOTNIS Winchester FORTIFIED FORD. CowayStates. ^rcijaeoltrstcal Journal. SEPTEMBER, 1866. THE CAMPAIGN OF AULUS PLAUTIUS.1 By EDWIN GUEST, LL.D., Master of Gonvil and Caius College, Cambridge. BEFORE we can discuss with, advantage the campaign of Aulus Plautius in Britain, it will be necessary to settle, or at least endeavour to settle, certain vexed questions which have much troubled our English antiquaries. The first of these relates to the place where Caesar crossed the Thames. -

Celtic Britain

1 arfg Fitam ©0 © © © © ©©© © © © © © © 00 « G XT © 8 i imiL ii II I IWtv,-.,, iM » © © © © © ©H HWIW© llk< © © J.Rhjsffi..H. © I EARLY BRITAIN, CELTIC BRITAIN. BY J. RHYS, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon/). Honorary LL.D. (Edin.). Honorary D.Litt. (Wales). FROFESSOR OF CELTIC IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD J PRINCIPAL OF JESUS COLLEGE, AND LATE FELLOW OF MERTON COLLEGE FELLOW OF THE BRITISH ACADEMY. WITH TWO MAPS, AND WOODCUTS OF COIliS, FOURTH EDITION. FUBLISHED UNDER THE D.RECTION OF THE GENERAL LITERATURE COMMITTEE. LONDON: SOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C. ; 43, queen victoria street, e.c. \ Brighton: 129, north street. New York : EDWIN S. GORHAM. iqoP, HA 1^0 I "l C>9 |X)VE AND MALCOMSON, LIMITED, PRINTERS, 4 AND 5, DEAN STREET, HIGH HOLBORN, LONDON, W.C. PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. These are the days of little books, and when the author was asked to add one to their number, he accepted the invitation with the jaunty simplicity of an inexperienced hand, thinking that it could not give him much trouble to expand or otherwise modify the account given of early Britain in larger works ; but closer acquaintance with them soon convinced him of the folly of such a plan— he had to study the subject for himself or leave it alone. In trying to do the former he probably read enough to have enabled him to write a larger work than this ; but he would be ashamed to confess how long it has occupied him. As a student of language, he is well aware that no severer judgment could be passed on his essay in writing history than that it should be found to be as bad as the etymologies made by historians are wont to be ; but so essential is the study of Celtic names to the elucidation of the early history of Britain that the risk is thought worth incurring.