070102-Prater-Engl..Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann

Naharaim 2014, 8(2): 210–226 Uri Ganani and Dani Issler The World of Yesterday versus The Turning Point: Art and the Politics of Recollection in the Autobiographical Narratives of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann “A turning point in world history!” I hear people saying. “The right moment, indeed, for an average writer to call our attention to his esteemed literary personality!” I call that healthy irony. On the other hand, however, I wonder if a turning point in world history, upon careful consideration, is not really the moment for everyone to look inward. Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man1 Abstract: This article revisits the world-views of Stefan Zweig and Klaus Mann by analyzing the diverse ways in which they shaped their literary careers as autobiographers. Particular focus is given to the crises they experienced while composing their respective autobiographical narratives, both published in 1942. Our re-evaluation of their complex discussions on literature and art reveals two distinctive approaches to the relationship between aesthetics and politics, as well as two alternative concepts of authorial autonomy within society. Simulta- neously, we argue that in spite of their different approaches to political involve- ment, both authors shared a basic understanding of art as an enclave of huma- nistic existence at a time of oppressive political circumstances. However, their attitudes toward the autonomy of the artist under fascism differed greatly. This is demonstrated mainly through their contrasting portrayals of Richard Strauss, who appears in both autobiographies as an emblematic genius composer. DOI 10.1515/naha-2014-0010 1 Thomas Mann, Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, trans. -

Crossing Central Europe

CROSSING CENTRAL EUROPE Continuities and Transformations, 1900 and 2000 Crossing Central Europe Continuities and Transformations, 1900 and 2000 Edited by HELGA MITTERBAUER and CARRIE SMITH-PREI UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press 2017 Toronto Buffalo London www.utorontopress.com Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-4426-4914-9 Printed on acid-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper with vegetable-based inks. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Crossing Central Europe : continuities and transformations, 1900 and 2000 / edited by Helga Mitterbauer and Carrie Smith-Prei. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4426-4914-9 (hardcover) 1. Europe, Central – Civilization − 20th century. I. Mitterbauer, Helga, editor II. Smith-Prei, Carrie, 1975−, editor DAW1024.C76 2017 943.0009’049 C2017-902387-X CC-BY-NC-ND This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivative License. For permission to publish commercial versions please contact University of Tor onto Press. The editors acknowledge the financial assistance of the Faculty of Arts, University of Alberta; the Wirth Institute for Austrian and Central European Studies, University of Alberta; and Philixte, Centre de recherche de la Faculté de Lettres, Traduction et Communication, Université Libre de Bruxelles. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council, an agency of the -

The Censorship of Literary Naturalism, 1885-1895: Prussia and Saxony

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Peer Reviewed Articles History Department 2014 The Censorship of Literary Naturalism, 1885-1895: Prussia and Saxony Gary D. Stark University of Texas at Arlington Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/hst_articles Part of the History Commons ScholarWorks Citation Stark, Gary D., "The Censorship of Literary Naturalism, 1885-1895: Prussia and Saxony" (2014). Peer Reviewed Articles. 19. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/hst_articles/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History Department at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peer Reviewed Articles by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYMPOSIUM: THE CENSORSHIP OF LITERARY NATURALISM The of Censorship Literary Naturalism, 1885-1895: Prussia and Saxony GARY D. STARK has been written in recent years about the emergence of modernist culture in^w de siecle Europe and the resistance MUCH it met from cultural traditionalists. The earliest clashes be? tween traditionalism and modernism usually occurred in the legal arena, where police censors sought to uphold traditional norms against the modernist onslaught. How successful was the state in combatting emer? gent modernist cultural movements? Arno Mayer, in a recent analysis ofthe persistence ofthe old regime in Europe before 1914, maintains that: "In the long run, the victory of the modernists may have been inevitable. In the short run, however, the modernists were effectively bridled and isolated, if need be with legal and administrative controls."1 In Germany, the first stirrings of modern literature?if perhaps not yet of full modernism?began with the naturalists, also called the "real- ists," the "youngest Germans," or simply "the Moderns."2 Naturalists Research for this essay was made possible by generous grants from the National En? dowment for the Humanities, the German Academic Exchange Service, and the Uni? versity of Texas at Arlington Organized Research Fund. -

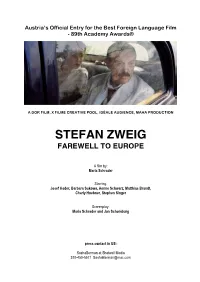

Stefan Zweig Farewell to Europe

Austria’s Official Entry for the Best Foreign Language Film - 89th Academy Awards® A DOR FILM, X FILME CREATIVE POOL, IDÉALE AUDIENCE, MAHA PRODUCTION STEFAN ZWEIG FAREWELL TO EUROPE A film by: Maria Schrader Starring: Josef Hader, Barbara Sukowa, Aenne Schwarz, Matthias Brandt, Charly Huebner, Stephen SInger Screenplay: Maria Schrader and Jan Schomburg press contact in US: SashaBerman at Shotwell Media 310-450-5571 [email protected] Table of Contents Short synopsis & press note …………………………………………………………………… 3 Cast ……............................................................................................................................ 4 Crew ……………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Long Synopsis …………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Persons Index…………………………………………………………………………………….. 14 Interview with Maria Schrader ……………………………………………………………….... 17 Backround ………………………………………………………………………………………. 19 In front of the camera Josef Hader (Stefan Zweig)……………………………………...……………………………… 21 Barbara Sukowa (Friderike Zweig) ……………………………………………………………. 22 Aenne Schwarz (Lotte Zweig) …………………………….…………………………………… 23 Behind the camera Maria Schrader………………………………………….…………………………………………… 24 Jan Schomburg…………………………….………...……………………………………………….. 25 Danny Krausz ……………………………………………………………………………………… 26 Stefan Arndt …………..…………………………………………………………………….……… 27 Contacts……………..……………………………..………………………………………………… 28 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Technical details Austria/Germany/France, 2016 Running time 106 Minutes Aspect ratio 2,39:1 Audio format 5.1 ! 2! “Each one of us, even the smallest and the most insignificant, -

Wir Brauchen Einen Ganz Anderen Mut. Stefan Zweig – Abschied Von Europa 3

Lobkowitzplatz 2, 1010 Wien www.theatermuseum.at JÄNNER 2014 Wir brauchen einen ganz anderen Mut. Stefan Zweig – Abschied von Europa 3. April 2014 bis 12. Jänner 2015 ZUR AUSSTELLUNG Als der österreichische Schriftsteller Stefan Zweig (1881–1942) 1934 nach England und in der Folge nach Brasilien emigrierte, verließ ein überaus erfolgreicher Autor Europa. Dennoch sind es zwei Werke, die Zweig erst im Exil verfasst hat, die heute sein Bild bestimmen. Im Blick auf Die Welt von Gestern und die Schachnovelle entdeckt das Theatermuseum Zweigs Leben und Werk auf neue Weise. Es ist die Perspektive der Vertreibung, die die Ausstellung charakterisiert. Angelpunkt der Gestaltung ist das „Metropol“, das als mondänes Hotel das Fin de siècle ebenso repräsentiert, wie es als Gestapo-Hauptquartier zum Schreckensort schlechthin wurde. PressefOTOS Die Bilder sind für die Berichterstattung über die Ausstellung frei und stehen zum Download bereit unter www.theatermuseum.at/presse/ © Stefan Zweig Centre Salzburg Lobkowitzplatz 2, 1010 Wien www.theatermuseum.at JÄNNER 2014 Trägt die Sprache schon Gesang in sich... Richard Strauss und die Oper 12. Juni 2014 bis 9. Februar 2015 ZUR AUSSTELLUNG Richard Strauss zählt zu den wichtigsten Komponisten der beginnenden Moderne und wurde als Opernkomponist in aller Welt geschätzt. Strauss unterhielt zahlreiche Verbindungen nach Wien, wo er zwischen 1919 und 1924 als Direktor der Wiener Staatsoper große Triumphe, aber auch zahlreiche Niederlagen erlebte. Anlässlich seines 150. Geburtstages präsentiert das Theatermuseum seine umfangreichen Strauss-Bestände, unter ihnen die Korrespondenz mit Hugo von Hofmannsthal sowie den großen Schatz an Bühnenbild- und Kostümentwürfen von Alfred Roller. PressefOTOS Die Bilder sind für die Berichterstattung über die Ausstellung frei und stehen zum Download bereit unter www.theatermuseum.at/presse/ © Theatermuseum. -

A Hero's Work of Peace: Richard Strauss's FRIEDENSTAG

A HERO’S WORK OF PEACE: RICHARD STRAUSS’S FRIEDENSTAG BY RYAN MICHAEL PRENDERGAST THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in Music with a concentration in Musicology in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: Associate Professor Katherine R. Syer ABSTRACT Richard Strauss’s one-act opera Friedenstag (Day of Peace) has received staunch criticism regarding its overt militaristic content and compositional merits. The opera is one of several works that Strauss composed between 1933 and 1945, when the National Socialists were in power in Germany. Owing to Strauss’s formal involvement with the Third Reich, his artistic and political activities during this period have invited much scrutiny. The context of the opera’s premiere in 1938, just as Germany’s aggressive stance in Europe intensified, has encouraged a range of assessments regarding its preoccupation with war and peace. The opera’s defenders read its dramatic and musical components via lenses of pacifism and resistance to Nazi ideology. Others simply dismiss the opera as platitudinous. Eschewing a strict political stance as an interpretive guide, this thesis instead explores the means by which Strauss pursued more ambiguous and multidimensional levels of meaning in the opera. Specifically, I highlight the ways he infused the dramaturgical and musical landscapes of Friedenstag with burlesque elements. These malleable instances of irony open the opera up to a variety of fresh and fascinating interpretations, illustrating how Friedenstag remains a lynchpin for judiciously appraising Strauss’s artistic and political legacy. -

Literaturverzeichnis

Literaturverzeichnis Peter Sprengel Geschichte der deutschsprachigen Literatur von 1900-1918 Von der Jahrhundertwende bis zum Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs Hier finden Sie die gesonderten Literaturangaben zu neunzig Autorinnen und Autoren, dessen Aufnahme den Rahmen von Peter Sprengel: Geschichte der deutschsprachigen Literatur 1900 - 1918. Von der Jahrhundertwende bis zum Ende des Ersten Weltkriegs, gesprengt hätte. Das umfangreiche Verzeichnis der Werk- und Briefausgaben, Personalbibliographien und der seit 1980 erschienenen monographischen Untersuchungen zu einzelnen oder mehreren Autoren reicht von Altenberg bis Stefan Zweig und berücksichtigt besonders den Zeitraum 1900 - 1918. A B · Peter Altenberg · Hermann Bahr · Hugo Ball · Emmy Ball-Hennings · Ernst Barlach · Johannes R. Becher · Gottfried Benn · Ernst Blass · Rudolf Borchardt · Jakob Boßhart · Max Brod · Arnolt Bronnen D E · Theodor Däubler · Albert Ehrenstein · Alfred Döblin · Carl Einstein · Paul Ernst · Herbert Eulenberg · Hanns Heinz Ewers F G · Lion Feuchtwanger · Stefan George · Leonhard Frank · Friedrich Glauser · Reinhard Goering · Albert Paris Gütersloh H J · Ernst Hardt · Hans Henny Jahnn · Walter Hasenclever · Ernst Jünger · Gerhart Hauptmann · Georg Hermann · Max Herrmann-Neisse · Hermann Hesse · Georg Heym · Kurt Hiller · Jakob van Hoddis · Hugo von Hofmannsthal K L · Franz Kafka · Gustav Landauer · Georg Kaiser · Else Lasker-Schüler · Eduard Graf von Keyserling · Alfred Lichtenstein · Klabund · Oskar Loerke · Oskar Kokoschka · Georg Lukács · Paul Kornfeld · Karl -

Inhalt. Seilt Geleitwort

Inhalt. Seilt Geleitwort. Von Clara Körben . 3 I. Aus österreichischem Geiste. Aphorismen. Von Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach 9 Der Schleier der Beatrice (Schlußverse). Von Arthur Schnitzler .... 10 Die verwandelte Welt. Von Hans Müller 11 Das Landgut der Fiametta. Von Raoul Auernheimer 13 Lemberg. Von Thaddäus Rittner 22 Die Flöte. Von Franz Karl Ginzkey 23 Die Helfenden. Von Lola Lorme 24 Bischof Dr. Rudolf Hittmair und Enrita von Handel-Mazzetti. Mitgeteilt von Enrika von Handel-Mazzetti (aus der Hittmair-Biographie von Pesendorfer) . 25 Ostermorgen im Felde. Von Mathilde Gräfin Stubenberg 30 Deutsches Wiegenlied. Von Alfons Petzold 30 Dem Hiasl fei Feldpost (steirisch). Von Hermann Kienzl 31 Der Sommer. Von Peter Attenberg 32 Der Frosch. Von Peter Altenberg 32 Deutsche Lehre. Von Hans Fraungruber 33 Die Leute vom blauen Guguckshaus. Von Emil Ertl (aus der Roman- Trilogie „Ein Volk an der Arbeit") 33 Adria-Idyllen. Von Irma von Höfer 45 England und die Kulturphilosophie Bacon-Shakespeares in ihren Beziehungen zum gegenwärtigen Weltkrieg. Von Hofrat Alfred von Weber-Ebenhof 50 St. Michael. Von Gabriele Fürstin Wrede 64 Echt österreichisch. Von Marianne Schrutka von Rechtenstamm ... 65 Zwei Tannen. Don Else Rubricius 66 II. An Österreichs Schwert. Zum 18. August 1915. Von Peter Rosegger 69 Das große Händefalten. Von Anton Wildgans 69 Mein Österreich. Von Richard Schaukal 71 Die Kriegssage vom Untersberg. Von GiselavonBerger 72 Die Glocken kommen. Von Angelika von Hörmann 76 Schwertbrüder. Von Karl Rogner 77 Österreichisches Reiterlied. Von Hugo Iuckermannf . 78 Przemysl. Von Maria Eugenia teile Grazie 79 Weihnachten in Przemysl. Von Herma von Skoda 80 Aus» Osterreich, aus. Von HermavonSkoda 81 5 Bibliografische Informationen digitalisiert durch N/" http://d-nb.info/362276870 31 "HEI1 Seite Mein Bub. -

I. Childhood and School Days

I. Childhood and School Days L¨ubeck, 1877 CHRONICLE 1875–1894 Thomas Mann, or to be precise, Paul Thomas Mann, was born on June 6, 1875, in L¨ubeck and baptized as a Protestant on June 11 in St. Mary’s Church. His parents were very refined people: Thomas Johann Heinrich Mann, born in L¨ubeck in 1840, and Julia Mann, n´ee da Silva-Bruhns, who had seen the light of day for the first time in 1851 in Brazil. His father was the owner of the Johann Siegmund Mann grain firm, further a consul to the Netherlands, and later the senator overseeing taxes for L¨ubeck, which joined the German Empire as an independent city-state in 1871. His mother came from a wealthy German-Brazilian merchant family. His older brother Hein- rich was born in 1871; the siblings born later were Julia, 1877; Carla, 1881; and Viktor, 1890. As was customary in his circles, instead of entering the public primary school or elementary school, from Easter 1882 on, Thomas Mann attended a private school, the Progymnasium of Dr. Bussenius, in which there were six grades. In addition to the three primary-school classes, there were the first, second, and third years of the secondary school. He was held back for the first time in the third year and had to repeat it. He transferred at Easter 1889 to the famed Katharineum on L¨ubeck’s K¨onigstrasse. Since he was to be- come a merchant, he did not attend the humanistic branch but rather the mathematical-scientific branch. -

The Idea of America in Austrian Political Thought 1870-1960

The Idea of America in Austrian Political Thought 1870-1960 David Wile Advisor: Dr. Alan Levine, School of Public Affairs University Honors Spring 2012 Wile 1 Abstract Between 1870 and 1960, the United States of America and Austria experienced two opposite political paths. The United States emerged from the wreckage of the Civil War as a more centralized republic and at the turn of the century became an imperial power, a status that the First and Second World Wars only solidified. Meanwhile, Austria ended the nineteenth century as one of Europe’s largest empires, yet after World War I, all that remained of the intellectual and cultural center of the Habsburg Empire was a tiny remnant cut off from its breadbasket in Hungary, its industrial center in Bohemia, and its seaports in the Balkans. Against the backdrop of a dying empire observing a nascent one, this project examines the discourse through which prominent members of the Austrian, and especially Viennese, intellectual elite imagined the United States of America, and attempts to determine which patterns emerged in that discourse. The Austrian thinkers and writers who are the major focus of this work are: the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, the Zionist Theodor Herzl, the feuilletonist and satirist Karl Kraus, two of the most prominent members of the Austrian School of economics, Ludwig von Mises and F.A. Hayek, and an economist of the Historical School, Joseph Schumpeter. To a lesser extent, the work refers to writers Stefan Zweig, Albert Kubin, and Arthur Schnitzler, philosophers Otto Weininger and Franz Brentano, and two more Austrian School economists, Carl Menger and Friedrich von Wieser. -

Cultural Amnesia

Marcel Reich-Ranicki arcel Reich-Ranicki (b. 1920), by far the most famous critic in Germany between World War II Mand the millennium, continues, into the twenty-first century, to exercise, over the German literary scene, a dominance which some writers prefer to regard as a reign of terror. Actually there can be no real argument about the fairness of his judgements – a fact which, of course, makes his disapproval feel even worse for those found wanting. He writes so well that his opinions are quoted verbatim. Victims of a put-down are thus faced with the prospect of becoming a national joke. Most of those writers whose later books were savaged by him had their early books praised by him: those are the writers who become most resentful of all against him. Well equipped to look after himself, he is hard to lay a glove on. Watching magisterial figures such as Günter Grass vainly trying to get their own back on Reich-Ranicki is one of the entertainments of modern Germany. Even those wounded by him would have to admit, under scopolamine, that he can be very funny when on the attack. Hence their intense enjoyment of the moment when history caught him out. Deported from Berlin to the Warsaw ghetto in 1938, Reich-Ranicki survived the Holocaust but stayed on in Communist Poland after the war, and first pursued literary criticism under East German auspices. When he finally defected to the West he forgot to tell anyone that he had been a registered informer under the regime he left behind. -

HERMANN BAHR KRITISCHE SCHRIFTEN XVIII HERMANN BAHR KRITISCHE SCHRIFTEN in EINZELAUSGABEN Herausgegeben Von Claus Pias HERMANN BAHR

HERMANN BAHR KRITISCHE SCHRIFTEN XVIII HERMANN BAHR KRITISCHE SCHRIFTEN IN EINZELAUSGABEN Herausgegeben von Claus Pias HERMANN BAHR SELBSTBILDNIS Herausgegeben von Gottfried Schnödl www.univie.ac.at/bahr Erstellt mit Mitteln des Österreichischen Wissenschaftsfonds (FWF): P 21186. © VDG Weimar 2011. Alle Rechte, sowohl der Übersetzung, des Nachdrucks und auszugsweisen Abdrucks sowie der fotomechanischen Wiedergabe vorbe- halten. Satz mithilfe einer LATEX-Klasse von Herbert Voss Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Bibliothek: Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.ddb.de> abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-89739-662-3 Das Digitalisat dieses Titels finden Sie unter: http://dx.doi.org/10.1466/20110112.09 Meiner Frau München, Ostern 1923 1 1 „Wie ein langes durchwandertes Tal vom Hügel gesehen wird.“ Goethe „Gott hat mir stets mehr gegeben, als ich verdient habe.“ Stifter I Daß ich, bevor es zu spät wird, noch mein Leben erzählen soll, muß ich immer wieder hören. Der Wunsch, so freundlich er klingt, ist mir verdächtig. Es steckt darin doch auch wieder das mich immer begleitende Vorurteil, ich sei von Person mehr wert als meine sämtlichen Werke. Daß man diese unterschätzt, wird der Tod, der alles ordnende, schon berichtigen. Ich kann nur versichern, daß man mich selber überschätzt. Es wird sich einst eher ergeben, daß ich mehr hervorgebracht, mehr aus mir herausgeholt, als eigentlich in mir enthalten war. Gerade dadurch werden freilich, im höchsten Sinne, auch meine Werke prekär, doch werden sie eben dadurch zu richtigen Ausdrücken ihrer Zeit, einer Zeit, deren Leistungen überall über ihr Maß gingen und weil sie sozusagen kein Recht auf sich hatten, irgendwie stets ihr schlechtes Gewissen merken ließen.