Sporting Clubs and Scandals – Lessons in Governance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ON the TAKE T O N Y J O E L a N D M at H E W T U R N E R

Scandals in sport AN ACCOMPANIMENT TO ON THE TAKE TONY JOEL AND MATHEW TURNER Contemporary Histories Research Group, Deakin University February 2020 he events that enveloped the Victorian Football League (VFL) generally and the Carlton Football Club especially in September 1910 were not unprecedented. Gambling was entrenched in TMelbourne’s sporting landscape and rumours about footballers “playing dead” to fix the results of certain matches had swirled around the city’s ovals, pubs, and back streets for decades. On occasion, firmer allegations had even forced authorities into conducting formal inquiries. The Carlton bribery scandal, then, was not the first or only time when footballers were interrogated by officials from either their club or governing body over corruption charges. It was the most sensational case, however, and not only because of the guilty verdicts and harsh punishments handed down. As our new book On The Take reveals in intricate detail, it was a particularly controversial episode due to such a prominent figure as Carlton’s triple premiership hero Alex “Bongo” Lang being implicated as the scandal’s chief protagonist. Indeed, there is something captivating about scandals involving professional athletes and our fascination is only amplified when champions are embroiled, and long bans are sanctioned. As a by-product of modernity’s cult of celebrity, it is not uncommon for high-profile sportspeople to find themselves exposed by unlawful, immoral, or simply ill-advised behaviour whether it be directly related to their sporting performances or instead concerning their personal lives. Most cases can be categorised as somehow relating to either sex, illegal or criminal activity, violence, various forms of cheating (with drugs/doping so prevalent it can be considered a separate category), prohibited gambling and match-fixing. -

Extract Catalogue for Auction 3

Online Auction 3 Page:1 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 958 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 958 Balance of collection including 1931-71 fixtures (7); Tony Locket AFL Goalkicking Estimate A$120 Record pair of badges; football cards (20); badges (7); phonecard; fridge magnets (2); videos (2); AFL Centenary beer coasters (2); 2009 invitation to lunch of new club in Reserve A$90 Sydney, mainly Fine condition. (40+) Lot 959 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 959 Balance of collection including Kennington Football Club blazer 'Olympic Premiers Estimate A$100 1956'; c.1998-2007 calendars (21); 1966 St.Kilda folk-art display with football cards (7) & Reserve A$75 Allan Jeans signature; photos (2) & footy card. (26 items) Lot 960 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 960 Collection including 'Mobil Football Photos 1964' [40] & 'Mobil Footy Photos 1965' [38/40] Estimate A$250 in albums; VFL Park badges (15); members season tickets for VFL Park (4), AFL (4) & Reserve A$190 Melbourne (9); books/magazines (3); 'Football Record' 2013 NAB Cup. (38 items) Lot 961 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 961 Balance of collection including newspapers/ephemera with Grand Final Souvenirs for Estimate A$100 1974 (2), 1985 & 1989; stamp booklets & covers; Member's season tickets for VFL Park (6), AFL (2) & Melbourne (2); autographs (14) with Gary Ablett Sr, Paul Roos & Paul Kelly; Reserve A$75 1973-2012 bendigo programmes (8); Grand Final rain ponchos. (100 approx) Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au 20 - 23 November 2020 Lot 962 FOOTBALL - AUSTRALIAN RULES Lot 962 1921 FOURTH AUSTRALIAN FOOTBALL CARNIVAL: Badge 'Australian Football Estimate A$300 Carnival/V/Perth 1921'. -

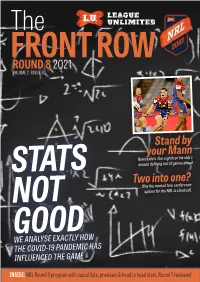

Round 8 2021 Row Volume 2 · Issue 8

The FRONT ROW ROUND 82021 VOLUME 2 · ISSUE 8 Stand by your Mann Newcastle's five-eighth on his side's STATS season defining run of games ahead Two into one? Why the mooted two-conference NOT system for the NRL is a bad call. GOOD WE ANALYSE EXACTLY HOW THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC HAS INFLUENCED THE GAME INSIDE: NRL Round 8 program with squad lists, previews & head to head stats, Round 7 reviewed LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM AUSTRALIA’S LEADING INDEPENDENT RUGBY LEAGUE WEBSITE THERE IS NO OFF-SEASON 2 | LEAGUEUNLIMITED.COM | THE FRONT ROW | VOL 2 ISSUE 8 What’s inside From the editor THE FRONT ROW - VOL 2 ISSUE 8 Tim Costello From the editor 3 Last week, long-serving former player and referee Henry Feature What's (with) the point(s)? 4-5 Perenara was forced into medical retirement from on-field Feature Kurt Mann 6-7 duties. While former player-turned-official will remain as part of the NRL Bunker operations, a heart condition means he'll be Opinion Why the conference idea is bad 8-9 doing so without a whistle or flag. All of us at LeagueUnlimited. NRL Ladder, Stats Leaders. Player Birthdays 10 com wish Henry all the best - see Pg 33 for more from the PRLMO. GAME DAY · NRL Round 8 11-27 Meanwhile - the game rolls on. We no longer have a winless team LU Team Tips 11 with Canterbury getting up over Cronulla on Saturday, while THU Canberra v South Sydney 12-13 Penrith remain the high-flyers, unbeaten through seven rounds. -

MAY 2018 EST 2010 EFC ISSUE 19 Hello and Welcome to Another

MAY 2018 EFC ISSUE 19 EST 2010 Mason Fletcher with JHA Coach Heath Hocking Hello and welcome to another James Hird Academy JHA ACCELERATION GROUP edition of the JHA Newsletter. Development Groups PLAYER AGE FATHER Daniel Hanna 18 NGA Jaxon Neagle 18 Merv Neagle Our first edition of 2018 will cover everything from our annual Guard JHA BABY BOMBERS Ismail Moussa 18 NGA Of Honour Game against Port Adelaide, to the commencement of PLAYER AGE FATHER Mason Fletcher 18 Dustin Fletcher our Acceleration Group’s training program, the completion of the Mara Lovett-Murray 8 Nathan Lovett-Murray Kyle Gillard 18 NGA first After-School session for the Flight Squad and the welcoming Aidan Ramanauskas 9 Adam Ramanauskas Jake Firebrace 17 NGA of new members to our father-son, Next Generation Academy and Logan Daniher 9 Chris Daniher Ricky O'Donnell 17 Gary O'Donnell international zoning applicant tiers. Taj McPhee 9 Adam McPhee Darcy Denham 17 Sean Denham Under the supervision of JHA coach and VFL captain Heath Hocking, Koby Bewick 9 Darren Bewick Kurtis Barnard 17 Paul Barnard the JHA has expanded to over 70 members across the Acceleration William Hird 9 James Hird Tom Hird 17 James Hird Group, the Flight Squad and the Baby Bombers programs. Max Alessio 8 Steve Alessio Kyle Baker 17 NGA Thomas Caracella 8 Blake Caracella Lachlan Johnson 16 NGA The commitment of the James Hird Academy to developing the skills Taitum Dempsey 8 Courtenay Dempsey Xavier Saly 16 NGA and off-field preparation awareness of talented junior footballers up Cove McPhee 7 Adam McPhee to 19 years of age has reaped rewards as, once again, the JHA is well Cody Brand 15 NGA Lucas Ramanauskas 7 Adam Ramanauskas represented amongst the ranks of TAC Cup side, the Calder Cannons. -

National Rugby League Lawn Bowls National Rugby League

SELECTIONS ~UNIQUE COFFINS ~ Celebrating through a beautiful funeral life 1 EXPRESSIONS COFFINS - $2290 EXPRESSIONS COFFINS - $2290 Gerbera Flowers Frangipani Flowers Gerbera Flowers Frangipani Flowers Pink Blossom Pink Blossom Succulents of Colour ashtonmanufacturing.com.au ashtonmanufacturing.com.au Pink Roses Mixed Flowers Pink Roses ashtonmanufacturing.com.au 2 Expressions Coffins Expressions Coffins 3 ashtonmanufacturing.com.au EXPRESSIONS COFFINS - $2290 EXPRESSIONS COFFINS - $2290 White Rose Golden Sunflower White Roses Golden Sunflower Pink & Purple Roses Sunflowers Blooming ashtonmanufacturing.com.au ashtonmanufacturing.com.au Red Roses Red Roses Rainbow Lorikeets 4 Expressions Coffins Expressions Coffins 5 ashtonmanufacturing.com.au EXPRESSIONS COFFINS - $2290 EXPRESSIONS COFFINS - $2290 Doves Released Leopard Print Doves Released Leopard Print Butterfly Migration Love Hearts Butterfly Migration Love Hearts ashtonmanufacturing.com.au ashtonmanufacturing.com.au Cloudy Sky Jelly Beans Cloudy Sky Jelly Beans ashtonmanufacturing.com.au ashtonmanufacturing.com.au 6 Expressions Coffins Expressions Coffins 7 ashtonmanufacturing.com.au ashtonmanufacturing.com.au EXPRESSIONS COFFINS - $2290 EXPRESSIONS COFFINS - $2290 Red Wood Green Tractor Red Wood Green Tractor Checker Plate Red Tractor Checker Plate Red Tractor ashtonmanufacturing.com.au ashtonmanufacturing.com.au Wheat Harvest Corrugated Iron Wheat Harvest ashtonmanufacturing.com.au ashtonmanufacturing.com.au 8 Expressions Coffins Expressions Coffins 9 ashtonmanufacturing.com.au -

Download PDF of Article from AFL Record

CHANGEOVER: Six clubs will be unveiling new senior coaches in 2014 – clockwise from left: Paul Roos (Melbourne), Adam Simpson (West Coast), Mark Thompson (Essendon), Leon Cameron (GWS Giants), Alan Richardson (St Kilda) and Justin Leppitsch (Brisbane Lions). THE COACHING CAPER FRESH & FAMILIAR FACES The AFL coaching landscape will have a different look in 2014. Four clubs will have rookie coaches – Leon Cameron (Greater Western Sydney), Alan Richardson (St Kilda), Justin Leppitsch (Brisbane Lions) and Adam Simpson (West Coast). Another two – Essendon and Melbourne – have lured back respected premiership coaches Mark Thompson and Paul Roos. What are their hopes and expectations? ASHLEY BROWNE They have an unbelievable passion for the game and for teaching the game HAWTHORN COACH ALASTAIR CLARKSON ON PROTEGES LEON CAMERON AND ADAM SIMPSON THE COACHING CAPER FRESH & FAMILIAR FACES n the ideal world, every new AFL coach would have landed his job in identical fashion. There would be development coaching, teaching the kids and learning to coach. Throw in some line coaching and perhaps a practice match or a NAB Challenge encounter as the senior coach just to get a taste for the big chair. At some stage, perhaps at the start or somewhere along the journey, Ithere would be a period as standalone coach at under-18 or state league level, where with every decision made, the buck stops with you. Coaching pathways have become a trendy topic, as illustrated by Hawthorn coach Alastair Clarkson in his remarks about the difficulties faced by James Hird during the Essendon supplements scandal. BACK IN THE FOLD: The point Clarkson tried to highlight Former premiership was whether Hird might have star Justin Leppitsch returns to the handled things better had he not Brisbane Lions as been thrust into the job at Essendon senior coach. -

Everyone to the Business Review of the 2014 Rugby League Year. I

Welcome everyone to the Business Review of the 2014 rugby league year. I start by paying my respects to the traditional owners of the land on which we meet today, The Gadigal people of the Eora nation, their elders past and present and their emerging leaders. The intention of the Business Review is to let our game’s key stakeholders know how the business performed in 2014 and what we’re focusing on in 2015. In my remarks I’ll comment on the results for 2014 and some observations on where our focus has been and where it will go during the next year. After this, our CEO Dave Smith will present to you in some detail on the business, and Todd Greenberg, our Head of Football, will talk to the football. Last year when we reported our results, it was the end of Dave’s first year as Chief Executive and the end of the first year of our new broadcast rights deal. Today we are further down the road, the achievements are many, but the challenges are also clearer to us all - as is the thinking on how to address them. 2014 in almost every aspect was a very good year and we should all feel the game of rugby league is in good shape and is getting stronger. The metrics to support this are very clear as you will see on the following slides. Of fundamental importance, financial performance has once again been very strong. Dave will take you through this in some detail shortly, but we are extremely pleased with the $49.9 m surplus we have delivered while we are simultaneously building the capability a professional organisation of this nature requires. -

Newsletter August 2017

Extracts from NEWSLETTER AUGUST 2017 A GREAT INITIATIVE OF THE “FARMERS DAY” BY KEVIN SHEEDY In the second year of the Farmers Round, the Bombers played Geelong on the MCG on Saturday May 13th. There were many stalls and entertainment for supporters outside the ground prior to the game, and Kevin Dale, a member of our Association and President of the Dick Reynolds Club and Collins Street Dons, was seen whipping up the boys before the game, it worked, because they had a great win . This event has become a great annual match and will only grow bigger in future years. Well done Sheeds. Two of our past players, Ian “Bluey” Shelton and Russell Blew, were invited to the Essendonians function prior to the game and are pictured with Peter Hughes, the President of the Essendonians. OUR ASSOCIATION SUPPORTS EFC APPLICATION TO FIELD A WOMEN’S TEAM The EFC has now officially submitted an application to the AFL to field a women’s team in the AFL in season 2019. As part of this application, we have confirmed that the same conditions would apply to women who represent the EFC at AFL or VFL to become members of our Association following their playing days, which we believe adds value to the application. There is of course no guarantee that the EFC will be granted a licence in 2019, however at some time in the future there will be a women’s team representing the club, which we should all support wholeheartedly. The article below should be of interest to all Bomber supporters. -

Australia Chapter in the Sports Law Review

the Sports Law Review Law Sports Sports Law Review Fifth Edition Editor András Gurovits Fifth Edition Fifth lawreviews © 2019 Law Business Research Ltd Sports Law Review Fifth Edition Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd This article was first published in December 2019 For further information please contact [email protected] Editor András Gurovits lawreviews © 2019 Law Business Research Ltd PUBLISHER Tom Barnes SENIOR BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Nick Barette BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Joel Woods SENIOR ACCOUNT MANAGERS Pere Aspinall, Jack Bagnall ACCOUNT MANAGERS Olivia Budd, Katie Hodgetts, Reece Whelan PRODUCT MARKETING EXECUTIVE Rebecca Mogridge RESEARCH LEAD Kieran Hansen EDITORIAL COORDINATOR Tommy Lawson HEAD OF PRODUCTION Adam Myers PRODUCTION EDITOR Helen Smith SUBEDITOR Janina Godowska CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Nick Brailey Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London Meridian House, 34-35 Farringdon Street, London, EC2A 4HL, UK © 2019 Law Business Research Ltd www.TheLawReviews.co.uk No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specific situation, nor does it necessarily represent the views of authors’ firms or their clients. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publishers accept no responsibility for any acts or omissions contained herein. Although the information provided was accurate as at November 2019, be advised -

Special NRL Grand Final Wrap-Around

South Sydney supporters talk of their love for the red and green Dream come true! Compiled by Renee Louise Azzopardi Laura Buzo, Mascot the game. I guess growing What are three qualities you field with Greg Inglis. No up in the Souths region had think make a true souths fan? team would measure up! a great influence on me. Loyalty. Support. Never- say-die attitude. Where will you be on grand Who is your favourite player final day and how will you and why? Where will you be on grand celebrate? Sam Burgess, because he final day and how will you This year I will be watching George Burgess (or is it Tom?), Kirisome Auva’a and Joel Reddy at Redfern Oval Photo: Kat Hines uses his full ability during celebrate? the grand final with my mum, an 80-minute game and is an If not at the game, I will grandma and friends. My inspiration to the rest of the gather some family and friends and I will get dressed team by leading the charge. friends to my place, have a up with red and green wigs Building up to JOEL BoRG, 14 large TV screen viewing of and face paint and we will What do you think Russell the game and when Souths jump up with joy when What does being a souths fan Crowe and Michael Maguire win I will enjoy the evening Souths win. I will re-watch something special mean to you? have brought to the club? celebrating with a party – I’ll the highlights after the grand I look forward to games Russell Crowe was able to bring out my very best scotch! final is played. -

Sir Peter Leitch Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 1st August 2018 Newsletter #228 We May Not Have Won But It Was Fantastic Meeting All The Fans! What the hell was that? By David Kemeys Former Sunday Star-Times Editor, Former Editor-in-Chief Suburban Newspapers, Long Suffering Warriors Fan ELL THAT was disappointing. This time last year we were deader than a dead thing, WSomeone forgot to tell the Titans they were canon-fodder for anyone. easy-beats. No one gave us a snowball’s chance in hell of being For the first 40 minutes they looked average, as in anything different this year – pretty much everyone fairness did we, a pretty good Shaun Johnson try tipping us for the wooden-spoon, yet here we are, apart. still eighth even after the disappointment in Queens- land. For the next 40 minutes they looked like world-beat- ers, and it was us who looked like, well, the Titans. But the Titans are a side we really should have had the depth, skill and courage to beat. We were without Tohu Harris, Adam Blair and Issac Luke, and boy did we miss them. If we lose to the Dragons this week, which most would certainly tip us to do, we will be in a tighter Simon Mannering had to wear the No 13 jersey and spot than we deserve. did not have his happiest day. Those who love knocking our boys will be all over On the other hand I was delighted to see Leivaha radio doing what they always do, shouting chokers Pulu back after way too long out. -

Australian Government Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority

Australian Government Unit 6, 5 Tennant Street I PO Box 1744 FYSHWICK ACT 2609 AUSTRALIA T 13 000 27232 1 +61 (0) 2 6222 4200 E asadal0asada.gov.au Australian Sports Anti-Doping Authority www.asada.gov.au 21 June 2016 Ms Joan Hird Via email only: [email protected] Dear Ms Hird Freedom of Information request 16-9 The purpose of this letter is to give you a decision about access to documents that you requested under the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOI Act). Background to Decision You requested access to documents relating to the Anti-Doping Rule Violation Panel (ADRVP) on 8 May 2016. Specifically you sought access to: • "... copies of records of ADRVP member discussions and meetings between ADRVP members and contact of ADRVP members with other persons in relation to the decision to place 34 Essendon players on the Register of Findings." Your request was received on Sunday 8 May 2016. An acknowledgment of your request was sent to you via email on Thursday 12 May 2016. That correspondence informed you that a decision was due to be made by Tuesday 7 June 2016. On 23 May 2016 you agreed to a 14 day extension of time under the terms of s15AA of the FOI Act. This made the date for a decision to be provided to you in this matter Tuesday 21 June 2016. Authority and Materials Considered I am an officer authorised under section 23(1) of the FOI Act to make decisions in relation to FOI re uests. In reaching my decision I have taken into consideration: • The relevant provisions of the FOI Act; • Relevant guidelines issued by the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner; and • Relevant Tribunal and Federal Court decisions concerning the operation of the FOI Act.