Grand Rapids Streetcar Route Refinement Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the Senate 94Th Legislature REGULAR SESSION of 2008

No. 34 STATE OF MICHIGAN Journal of the Senate 94th Legislature REGULAR SESSION OF 2008 Senate Chamber, Lansing, Tuesday, April 15, 2008. 10:00 a.m. The Senate was called to order by the President, Lieutenant Governor John D. Cherry, Jr. The roll was called by the Secretary of the Senate, who announced that a quorum was present. Allen—present Garcia—present Pappageorge—present Anderson—present George—present Patterson—present Barcia—present Gilbert—present Prusi—present Basham—present Gleason—present Richardville—present Birkholz—present Hardiman—present Sanborn—present Bishop—present Hunter—excused Schauer—present Brater—present Jacobs—present Scott—present Brown—present Jansen—present Stamas—present Cassis—present Jelinek—present Switalski—present Cherry—present Kahn—present Thomas—present Clark-Coleman—present Kuipers—present Van Woerkom—present Clarke—present McManus—present Whitmer—present Cropsey—present Olshove—present 644 JOURNAL OF THE SENATE [April 15, 2008] [No. 34 Reverend Christopher J. Pittman of Church of Cassopolis of Cassopolis offered the following invocation: Heavenly Father, in the name of Jesus, we thank You this morning for another day and an opportunity to lift up Your name—Mighty God, Creator of man and the universe, and Savior of mankind. As we gather together this morning in the Michigan Senate, we ask for Your presence. We need You to be a leader and a guide to the men and women who represent the state of Michigan, for without You, we are but mortal men making decisions that are much larger than we are. Lord, we know that You know the needs of the state of Michigan, and, God, we ask You today as we discuss that You would endow us with Your wisdom, with Your power, God, to make decisions that are divinely influenced. -

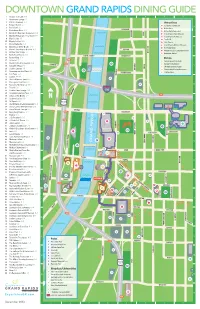

Downtown Grand Rapidsdining Guide

DOWNTOWN GRAND RAPIDS DINING GUIDE 1 Angel’s Thai Cafe H-5 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 2 Apartment Lounge I-7 88 13 3 B.O.B.’s Brewery J-4 Attractions 4 Bagger Dave’s J-3 C Gerald R. Ford Museum A A 5 Bar Divani J-5 D DeVos Place LEONARD 6 Bartertown Diner J-8 G DeVos Performance Hall A 7 Bentham’s Riverfront Restaurant H-4 L Grand Rapids Public Museum ONROE 8 Big Boy Restaurant - Pearl Street H-1 IONI M P Grand Rapids Art Museum 9 Big O’s Cafe I-5 T The B.O.B. 10 Biggby Coffee H-5 V Civic Theatre 11 Bistro Bella Vita K-4 W Grand Rapids Children’s Museum B B 12 Bobarino’s at The B.O.B. J-4 N 38 Y Van Andel Arena 13 Brann’s Steakhouse & Grille A-1 MASON Z Urban Institute of Contemporary Arts 14 Buffalo Wild Wings J-5 DIVISIO BB Downtown Market 15 Bull’s Head Tavern H-5 SIXTH STREET NEWBERRY 16 Burger King H-1 Hotels 86A 17 CC Cafe F-5 M Amway Grand Plaza Hotel 18 Charley’s Crab Restaurant K-3 86B B K Holiday Inn Downtown FOUR A C 19 Cinco De Mayo I-5 C TH ST AWA N JW Marriott Grand Rapids T 20 CitySen Lounge I-5 IONI E 68 OT S Courtyard by Marriott Downtown 21 Cornucopia at the Plaza H-4 A TROWBRIDGE U CityFlats Hotel 22 Cult Pizza J-8 ONRO M 23 Cygnus 27 H-4 P 24 Donk’s Mexican Joint H-5 77B 25 Flanagan’s Irish Pub H-5 D 26 Founders Brewing Co. -

2017 - 2018 Annual Report

2017 - 2018 ANNUAL REPORT west central michigan We need to believe. 2017-18 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Believe survivors. Believe domestic abuse and sexual assault happen. Doug Wilterdink, President Believe the uncomfortable truth that people we know are capable of Lonna Wiersma, Vice President violence. Believe there are structures in place that protect offenders. Believe we can be part of the problem, but also part of the solution. Believe that Peggy Bishop, Treasurer domestic and sexual violence are not inevitable – they are preventable. India Manns, Secretary Believe the world can be different. Janean Couch Karen Ender Believing is an act of hope. And it’s what supporters like you do – recognizing Barbara Griffin that you can help, that you can change things. Julia Guevara Your support of the YWCA makes an impact for the 4,000+ served here each Meg Hackett year, and also for our community and beyond. You change lives, you change Bryan Houck laws, you change attitudes. The numbers and stories in this report show just Rhonda Huismann how transformative that can be. Kathy Koch Thanks to you, we can support survivors with quality comprehensive Sherwin Robinson services, and make bold change through prevention and empowerment Cindy Rogowski programming. You act in the belief that change is possible – and it makes all Precious Threats the difference.Thank you. Michelle VanTorre-Tellier Jan Winters Eliminating Racism Charisse Mitchell, CEO Empowering Women and Girls Promoting Peace, Justice, Freedom, and Dignity for All Charisse Mitchell Doug Wilterdink -

2007-2009 COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY for Allegan, Ionia, Kent, Mecosta, Montcalm, Osceola, and Ottawa Counties

2007-2009 COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY For Allegan, Ionia, Kent, Mecosta, Montcalm, Osceola, and Ottawa Counties Prepared by the WEST MICHIGAN REGIONAL PLANNING COMMISSION _________________________________ submitted as Region 8's Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (CEDS) in accordance with requirements of the U.S. Economic Development Administration ________________ September 2007 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 5 U.S. Economic Development Administration Investment Policy Guidelines 5 Vision Statement 7 Mission Statement 8 Summary of Goals 8 Changes in EDA Rules 9 Organization and Management 11 WMRPC Board 11 WMRPC Executive Committee 14 Regional CEDS Committee 14 WMRPC Staff 14 CEDS Preparation and Approval Process 16 Public and Private Sector Involvement 16 Scheduled Meetings and General Agenda Items 17 Focus Areas 18 Economic Development Partners 20 Federal Programs 20 State of Michigan Programs/Statewide Organizations 22 Regional Programs 24 Allegan County 26 Ionia County 28 Kent County 30 Mecosta County 31 Montcalm County 33 Osceola County 35 Ottawa County 37 Other Partners 40 Community Profile 41 Region 8 41 Economic Clusters in Region 8 53 Allegan County 56 Ionia County 61 Kent County 66 Mecosta County 71 Montcalm County 76 Osceola County 81 Ottawa County 86 Goals and Objectives 91 Organizational Goals and Objectives 91 Community and Economic Development Goals and Objectives 93 Community Projects 95 Economic Development Administration Specific Projects 95 Community Development Projects 95 Vital Projects -

State of the System Report Comprehensive Operational Analysis the Rapid

The Rapid Comprehensive Operational Analysis | State of the System The Rapid State of the System Report Comprehensive Operational Analysis The Rapid FINAL November 2019 Nelson\Nygaard Consulting Associates Inc. | i Comprehensive Operational Analysis | State of the System The Rapid Table of Contents Page 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................1-1 Project Goals .......................................................................................................................................... 1-1 Report Organization ............................................................................................................................. 1-2 2 Document Review ............................................................................................................2-1 Key Findings ............................................................................................................................................ 2-1 Plan Review ............................................................................................................................................. 2-2 3 Market Analysis ...............................................................................................................3-1 Key Findings ............................................................................................................................................ 3-2 Population .............................................................................................................................................. -

Interurban Transit Partnership PRESENT PERFORMANCE

Interurban Transit Partnership Present Performance & Service Committee Members Charis Austin David Bilardello (Chair) Tracie Coffman Steven Gilbert Andy Guy PRESENT PERFORMANCE & SERVICE COMMITTEE Tuesday, May 11, 2021 – 4 p.m. Virtual Meeting AGENDA PRESENTER ACTION 1. PUBLIC COMMENT 2. MINUTES REVIEW – March 9, 2021 David Bilardello Approval 3. DISCUSSION a. Ridership Report Max Dillivan Information b. On-Time Performance Max Dillivan Information c. Township Contract Status: Cascade, Plainfield, Byron Nick Monoyios Information g. COA Status Update / Summer Service Nick Monoyios Information d. Safety Update Steve Luther Information e. Capital Program Update Kevin Wisselink Information 1) RCS Construction 2) Canopy Maintenance f. Recruiting Class Update / Employee Attrition Nancy Groendal Information 4. ADJOURNMENT Next meeting: July 13, 2021 MISSION: To create, offer and continuously improve a flexible network of public transportation options and mobility solutions. Interurban Transit Partnership 2 Present Performance & Service Committee Members Charis Austin David Bilardello (Chair) Tracie Coffman Steven Gilbert Andy Guy PRESENT PERFORMANCE & SERVICE COMMITTEE MEETING MINUTES Tuesday, March 9, 2021 – 4 p.m. Virtual Meeting ATTENDANCE: Committee Members Present: Charis Austin, David Bilardello, Steven Gilbert, Andy Guy Committee Members Absent: Tracie Coffman Staff Attendees: Max Dillivan, Julie Ilbrink, Bill Kirk, Steve Luther, Linda Medina, Nick Monoyios, James Nguyen, Deb Prato, Andy Prokopy, Steve Schipper, Mike Wieringa, Kevin Wisselink Other Attendees: Mr. Bilardello called the meeting to order at 4:04 p.m. 1. PUBLIC COMMENT No public comments were offered. 2. MINUTES – January 12, 2021 The minutes from January 12, 2021 were distributed and reviewed. Minutes were approved as written. 3. DISCUSSION a. Transit Asset Management Policy and Plan Mr. -

Accessibility Guide

Welcoming Everyone The Grand Rapids area strives to be a comfortable and convenient destination for all visitors, including those with special needs. We have been ranked the #2 city in America for people with disabilities, and we are always working to make our systems and services even more accessible. This guide, produced in conjunction with Disability Advocates of Kent County, outlines the accessibility features at some popular hotels, attractions, eateries and service providers in downtown Grand Rapids. Much of the reporting focuses on the experience of the wheelchair user, but there is also useful information for those with visual, auditory and other needs. We invite you to use this guide to identify properties that meet your specific needs as you travel around Grand Rapids. We’ll update the guide annually to add more reviews of locations across the city – so please, come back and visit us again! Updated: 12/20/2019 More visitor information at ExperienceGR.com/Accessibility Contents Attractions............................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Art Van Sports Complex ...................................................................................................................................................... 7 Calder Plaza ......................................................................................................................................................................... 9 The DeltaPlex -

Align Transit Improvement Plan

THE RAPID’S TRANSIT IMPROVEMENT PLAN williams&works 8/8/2018 ALIGN The Rapids Transit Improvement Study 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 5 PROJECT GOALS AND EVALUATION 9 State of The Rapid System 10 Align Project Goals 12 Public Engagement 16 Getting the Word Out 16 Project Evaluation Process 18 PROJECT TYPES 21 Improvement Project Categories 22 IMPLEMENTATION STRATEGY 39 Implementation Phasing 42 Explore Mobility On Demand 43 Making Regional Land Use More Transit Friendly 44 Partnership Based Implementation 45 Measuring Success 46 APPENDIX A: ALIGN PROJECT LOCATIONS 49 ALIGN The Rapids Transit Improvement Study 3 ALIGN The Rapids Transit Improvement Study 4 1 INTRODUCTION Align: The Rapid’s Transit Improvement Study is a year-long project led by The Interurban Transit Partnership (aka The Rapid), which identified, analyzed, and prioritized a set of transit improvements that can be made to the existing bus system to improve the transit experience in Grand Rapids and the surrounding communities. The Study looks for ways to add to and improve the network, recommends land use best practices and other policies to help grow ridership, and determines the improvements the public would like to see for the system. This study builds upon The Rapid’s previous transit projects, The Silver Line Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) and the Laker Line BRT, to identify opportunities to improve and potentially expand transit service within the urbanized area. The study explores the feasibility of implementing new BRT corridors, constructing infrastructure enhancements to improve bus travel time and reliability statistics, along with introducing amenity enhancements to improve rider comfort at bus stops and improve the visibility of transit in the community. -

Coordinated Mobility Plan: Prosperity Region 4

Coordinated Mobility Plan: Prosperity Region 4 Counties Allegan Barry Ionia Lake Kent Mason Mecosta Montcalm Muskegon Newago Oceana Osceola Ottawa May 2016 Prepared for Michigan 2-1-1 and Michigan Department of Transportation Prepared by KFH Group, Inc. Bethesda, Maryland Acknowledgements This plan is a component of a Veterans Transit Community Living Initiative (VTCLI) grant through the Federal Transit Administration (FTA). Michigan 2-1-1 and the Michigan Department of Transportation’s (MDOT) Office of Passenger Transportation led a statewide transportation study to identify regional gaps in mobility, particularly for people with limited transportation options such as veterans, older adults, individuals with disabilities and people with lower incomes. The result of the statewide study is ten coordinated mobility plans based geographically on Governor Snyder’s Prosperity Initiative. This is the Coordinated Mobility Plan for Prosperity Region 4. The statewide study built upon efforts by MDOT and Regional Planning Agencies and Metropolitan Planning Organizations to document what is known about regional transit mobility. These efforts were in response to the Governor’s special message to the legislature on the topic of aging, titled “Making Michigan a Great Place to Live Well and Age Well”. Advisory Committee The statewide transportation study was guided by the following advisory committee: Tom Page, Michigan 2-1-1 Clark Harder, Michigan Public Transit Scott Dzurka, Michigan Association of United Association Ways Donna McDowell, City of Livonia Maricela Alcala, Gryphon Place 2-1-1 MaLissa Schutt, Shiawassee Area Andy Brush, Michigan Dept of Transportation Transportation Agency Gale Capling, Clinton Area Transit System Valerie Shultz, Michigan Dept of Felicia Cross, City of Livonia Transportation Corey Davis, Muskegon Area Transit System Sheryl D. -

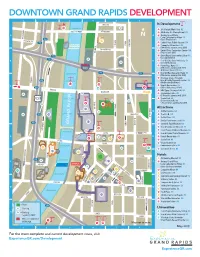

Downtown Grand Rapids Development

LEONARD E A IONI DOWNTOWN GRAND RAPIDSMONRO DEVELOPMENT 1 2 3 4 5 6 MASON In Development 14 P 1 201 Market (Multi-Use) H2 SIXTH STREET NEWBERRY 2 449 Bridge St. (Dining/Living) C1 DWAY A N A 3 Amway Grand Plaza, Curio Collection by Hilton E4 BROA 86A N (Hotel Renovation) F OURTH ST 29 A 4 86B AWA Calder Plaza (Public Square) D4 T IONI DIVISIO 5 Canopy by Hilton Hotel H4 OT OE (164 rooms, opening early 2020) TROWBRIDGE 6 DeVos Place Convention Center D4 MONR (Expansion/Hotel) 77A 7 Grand Rapids Community College E6 (School Building) 77B P B B 8 Grand Valley State University C6 P (School Buildings) 9 Hyatt Place Hotel E5 (160 rooms, opening mid 2019) & Warner Tower (Office) 77C 77C 10 Marriott Residence Inn Hotel G5 (146 rooms, opening late 2020) R 11 Michigan State University RNE 85B Grand Rapids Research Center C4 TU (Healthcare Buildings) 12 11 12 Rapids Restoration C3 C 2 C 86B 36 8 (Urban Whitewater Park) BRIDGE 13 RDV Corp. (Business HQ) E4 MICHIGAN P 30 14 P Staybridge Suites A3 (110 rooms, opening mid 2019) R 15 Studio Park H4 P P (Entertainment/Retail/ Office/Living), opening Fall 2019 P 6 4 MONROE Attractions 18 TTAWA O D P D 16 20 Monroe Live G4 CRESCENT P 86A 20 CRESCENT 17 The B.O.B. G4 BOSTWICK 18 DeVos Place D4 19 DeVos Performance Hall D4 85B 19 A GRAND RIVE 20 Gerald R. Ford Museum D2 DIVISION IONI 21 Grand Rapids Art Museum F5 13 SCRIBNER 22 P Grand Rapids Children’s Museum G6 LYON LYON 23 Grand Rapids Public Museum F2 E P E 12 Rapids Restoration C3 3 P 9 32 15 Studio Park H4 PEARL OM PEARL 24 UrbanS Institute for 7 ContemporaryAN Arts G6 31 R P 34 25 Van Andel Arena G4 23 33 ONT Hotels VERNON FOUNTAIN . -

Report to Congress: Transit Green Building Plan

REPORT TO CONGRESS TRANSIT GREEN BUILDING ACTION PLAN Prepared by the Federal Transit Administration July 2009 This page intentionally left blank. 2 Table of Contents Results in Brief ......................................................................................................................... 5 Analysis of Green Building Rating Systems ........................................................................ 5 Overview of Certified Green Building Transit Projects ....................................................... 6 Federal Assistance to Transit Agencies ................................................................................ 7 Planned FTA Actions, Timelines, and Resources ................................................................ 7 Background............................................................................................................................... 8 Analysis of Green Building Rating Systems Suitable for Transit Projects .............................. 9 Overview of Certified Green Building Transit Projects ......................................................... 15 Examples of Transit Green Building .................................................................................. 16 Federal Assistance to Transit Agencies .................................................................................. 22 FTA Research, Planning, Technical Assistance and Capital Grants .................................. 22 Flexible Funding Programs from the Highway Trust Fund............................................... -

Downtown Shoppingdeals

DOWNTOWN SHOPPING DEALS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Rent One Bike - Get One Free Central District Cyclery I6 Attractions 20% Off Entire Purchase C Gerald R. Ford Museum A LEONARD A Central District Cyclery I6 D DeVos Place A Sanctuary Folk Art L6 G DeVos Performance Hall ONROE IONI 10% Off Entire Purchase M L Grand Rapids Public Museum 6.25 Paper Studio I6 P Grand Rapids Art Museum Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum G2 T The B.O.B. Grand Rapids Art Museum Store I5 V Civic Theatre N Humanity Boutique I6 B W Grand Rapids Children’s Museum B MASON Old World Olive Co. I5 Y Van Andel Arena Deals are not available September 24 - October 12, 2014 DIVISIO Z Urban Institute of Contemporary Arts (ArtPrize) or December 31, 2014 (New Year’s Eve). Offers expire May 31, 2015. Does not include tax. SIXTH STREET NEWBERRY BB Downtown Market Additional restrictions may apply. 86A Hotels 86B M Amway Grand Plaza Hotel 1 (106) Gallery and Studio L7 FOURTH ST B A C AWA K Holiday Inn Downtown C 2 6.25 Paper Studio I6 T IONI E 3 Bianka Bridal H5 OT N JW Marriott Grand Rapids 4 Brian’s Books J7 A TROWBRIDGE S Courtyard by Marriott Downtown 5 Central District Cyclery I6 ONRO 6 Craft-Revival Jewelers J5 M U CityFlats Hotel 7 Curiosity Shop at the P Grand Rapids Public Museum H2 77B 8 DENYM E1 P 9 Downtown Market Shops O5 D D Aperitivo Crescent Street Floral Dorothy & Tony’s Gourmet Kettle Corn 85B 77C Field & Fire Bakery Fish Lads N R Grocer’s Daughter Chocolate 38 43 Love’s Ice Cream TURNE Making Thyme Kitchen E 8 E Montello Meat Market Old World Olive Co.