“Humanitarian Minimum”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Gaza Industrial Zone – Concept Note

North Gaza Industrial Zone – Concept Note A Private Sector-Led, Growth and Employment Promoting Solution December 19, 2016 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction: Purpose and Structure of the Concept Note 5 Chapter One: Current Realities of the Gaza Economy and Private Sector 6 The Macro Economic Anomaly of Gaza: the Role of External Aid, and the Impact of Political Conditions and Restrictions 6 Role of External Aid 6 The Effect of Political Developments and Restrictions 8 The Impact of Gaza on Palestine's Macro Economic Indicators 9 Trade Activity 9 Current Situation of the Private Sector in Gaza 12 Chapter Two: The proposed Solution - North Gaza Industrial Zone (NGIZ) 13 A New Vision for Private- Sector-Led Economic Revival of Gaza 13 The NGIZ – Concept and Modules 13 Security, Administration and Management of the NGIZ 14 The Economic Regime of the NGIZ and its Development through Public Private Partnership 16 The NGIZ - Main Economic Features and Benefits 18 Trade and Investment Enablers 19 Industrial Compounds 20 Agricultural Compounds 22 Logistical Compounds 24 Trade and Business Compounds 24 Energy, Water and Wastewater Infrastructure Compounds 26 The Erez Land Transportation Compound 27 The Gaza Off-Shore Port Compound 27 Chapter Three: Macro-Economic Effects in comparison to relevant case studies 29 Effect on Employment 29 Effect on Exports and GDP 30 Are Such Changes Realistic? Evidence and Case Studies 33 Evidence from Palestinian and Gazan Economic History 35 List of References 36 Annex A: Private Sector Led Economic Revival of Gaza – An Overview 38 Introduction: The Economic Potential of Gaza 38 Weaknesses and strengths of the Private Sector in Gaza 38 Development Strategy Based on Leveraging Strengths 40 Political Envelope and Economic Policy Enabling Measures 41 Trade Policy Enablers 42 Export and Investment Promotion Measures 44 Solutions for the Medium and Longer Terms 45 2 Executive Summary The purpose of this concept note is to propose a politically and economically feasible solution that can start the economic revival of Gaza. -

Radio 4 Listings for 6 – 12 June 2009 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 06 JUNE 2009 Political Correspondent Terry Stiasny and Professor John Claiming a Nazi Pedigree

Radio 4 Listings for 6 – 12 June 2009 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 06 JUNE 2009 Political correspondent Terry Stiasny and Professor John claiming a Nazi pedigree. Curtice discuss increasing pressure placed on the prime minister SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b00kr7fs) after cabinet resignations. Steve speaks to Balham locals, including Radio 4 favourite The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. Arthur Smith, and tracks down experts. He explores the reality Followed by Weather. James Naughtie details the ceremonies marking the 65th behind the Nazis' spy operation and their plans for invasion, anniversary of the D-Day landings. gaining privileged access to the original documentation detailing the Third Reich's designs on Britain. SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b00kvg9j) Correspondent Alex Bushill meets Roger Mansfield, one of the Claire Harman - Jane's Fame first men to try surfing in Cornwall. SAT 11:00 The Week in Westminster (b00krgd6) Episode 5 David Gleave, who runs the consultancy firm Aviation Safety It's been a tumultuous political week in which, for a while, Investigations, discusses news that debris salvaged from the sea Gordon Brown's grip on government appeared to loosen. Alice Krige reads from Claire Harman's exploration of Jane was not from the Air France jet that went missing. Austen's rise to pre-eminence from humble family scribblings A clutch of ministers resigned. But, after carrying out a to Hollywood movies. Samantha Washington, of Money Box, explains claims that car reshuffle, the Prime Minister insisted that HE would not walk insurers are 'bullying' people to settle claims when they have away. -

Norman G. Finkelstein

Gaza an inquest into its martyrdom Norman G. Finkelstein university of california press University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2018 by Norman G. Finkelstein Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Finkelstein, Norman G., author. Title: Gaza : an inquest into its martyrdom / Norman G. Finkelstein. Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifi ers: lccn 2017015719 (print) | lccn 2017028116 (ebook) | isbn 9780520968387 (ebook) | isbn 9780520295711 (cloth : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Human rights—Gaza Strip. | Palestinian Arabs—Crimes against—Gaza Strip. | Arab-Israeli confl ict—1993– | Gaza Strip— History—21st century. Classifi cation: lcc jc599.g26 (ebook) | lcc jc599.g26 f55 2018 (print) | DDC 953/.1—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017015719 Manufactured in the United States of America 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Gaza praise for gaza “ Th is is the voice I listen for, when I want to learn the deepest reality about Jews, Zionists, Israelis, and Palestinians. Norman Finkelstein is surely one of the forty honest humans the Scripture alludes to who can save ‘Sodom’ (our Earth) by pointing out, again and again, the sometimes soul-shriveling but unavoidable Truth. -

Saturday 28 December 2019 12:04 All Night Programme 6:08 Storytime 7

Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason explores Matilda and the Forgetments, by the history of instruments and Lorinda Creighton, told by Rashmi 3:04 The 3 O'Clock Drama studio innovations which have Pilapitaya; The Wicked Stepmother, shaped popular music over the past by Dugald Ferguson, told by Highlighting radio playwriting and century and speaks to musicians, Matthew Chamberlain; Royal performance (RNZ) producers, engineers and inventors Babysitters, by Joy Cowley, told by 4:06 A History of Music and Saturday 28 December 2019 - Early Electronic Music Pioneers (2 Stephen Clements; Mosley's Dad, by Technology of 9, BBC) Norman Bilbrough, told by Turei 12:04 All Night Programme Reedy (RNZ) Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason explores the history of instruments and A selection of the best RNZ National 5:00 The World at Five 7:30 Insight studio innovations which have interviews and features including A roundup of today's news and An award-winning documentary shaped popular music over the past 3:05 Fish 'n' Chip Shop Song by Carl sport (RNZ) programme providing century and speaks to musicians, Nixon (RNZ) 5:10 White Silence comprehensive coverage of national producers, engineers and inventors 6:08 Storytime and international current affairs - The Electric Guitar (3 of 9, BBC) The Caravan - 40 years after Air New (RNZ) The Silkies, by Anthony Holcroft, told Zealand Flight TE901 crashed into by Theresa Healey; Helper and the side of Mount Erebus disaster, 8:10 The Weekend with Lynn 5:00 The World at Five Helper, by Joy Cowley, told by Moira 'White Silence' tells the -

No Exit? Gaza & Israel Between Wars

No Exit? Gaza & Israel Between Wars Middle East Report N°162 | 26 August 2015 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Gaza after the War ............................................................................................................ 2 A. National Consensus in Name Only ............................................................................ 2 B. Failure to Reconstruct ............................................................................................... 4 C. Coming Apart at the Seams ....................................................................................... 5 D. Fraying Security Threatens a Fragile Ceasefire ......................................................... 8 E. Abandoned by Egypt .................................................................................................. 10 F. Israel’s Slight Relaxation of the Blockade ................................................................. 12 III. The Logic of War and Deterrence ................................................................................... -

2 Letter from the Director 3 Cmes Opens Field Office in Tunisia 6 News and Notes 26 Event Highlights

THE CENTER FOR MIDDLE EASTERN STUDIES NEWS HARVARD UNIVERSITY 2016–17 2 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR A message from William Granara 3 CMES OPENS FIELD OFFICE IN TUNISIA Inaugural celebration 6 NEWS AND NOTES Updates from faculty, students, alumni, and visiting researchers; Margaux Fitoussi on the Hara of Tunis; Q&A with Emrah Yildiz 26 EVENT HIGHLIGHTS Lectures, workshops, and conferences; Maribel Fierro’s view of Medieval Spain; the art of Helen Zughaib LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR 2016–17 HIGHLIGHTS WE COME TO THE END OF ANOTHER ACADEMIC YEAR about which CMES can boast an impressive list of accomplishments. It was a year in which we welcomed the largest cohort of our AM program, 15, increasing this year’s total enrollment to 28 students! I’m happy to report that we will be receiving 18 AM students next fall, testament to a highly successful and thriving master’s program in Middle Eastern studies at Harvard. A highlight of spring semester was the official opening and inaugural celebration of the CMES Tunisia Office, which we have been planning for the past three years. Mr. Hazem Ben-Gacem, AB ’92, our host and benefactor, opened the celebrations. Margot Gill, FAS Administrative Dean for International Affairs, and Malika Zeghal, Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Professor in Contemporary Islamic Thought and Life, joined me in welcoming our Tunisian guests, along with Melani Cammett, Professor of Government, Lauren Montague, CMES Executive Director, and Harry Bastermajian, CMES Graduate Programs Coordinator. Ten graduate students participated in our second annual Winter Term program in Tunis and were also part of the hosting committee for the event. -

2008 Edward Said Memorial Lecture Edward Said Memorial Lecture Dr Sara

2008 EDWARD SAID MEMORIAL LECTURE DELIVERED BY DR SARA ROY ELEVENTH OF OCTOBER 2008 AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ADELAIDE Copyright, The University of Adelaide 2 Copyright © The University of Adelaide 2008 Unless expressly stated otherwise, the University of Adelaide claims copyright ownership of all material on this document. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form (attaching a copy of this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use. The University of Adelaide reserves the right to revoke such permission at any time. Apart from this permission and uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 , all other rights are reserved. Requests for further authorisations, including authorisations to use material on this document for commercial purposes, should be directed to [email protected] . Published by: The University of Adelaide Editor: Dr Bassam Dally Date: October 2008 For further information about the lecture please contact: Associate Professor Bassam Dally Secretary, Steering Committee Edward Said Memorial Lecture The University of Adelaide SA, 5005, Australia Email: [email protected] Tel: +61-8-8303 5397 Fax: +61-8-8303 4367 3 THE IMPOSSIBLE UNION OF ARAB AND JEW: REFLECTIONS ON DISSENT, REMEMBRANCE AND REDEMPTION 1 SARA ROY After Edward’s death Mahmoud Darwish, the Palestinian poet who recently passed away, wrote a poem bidding Edward farewell. I would like to read a passage from that poem: He also said: If I die before you, my will is the impossible. I asked: Is the impossible far off? He said: A generation away. I asked: And if I die before you? He said: I shall pay my condolences to Mount Galiliee, and write, “The aesthetic is to reach poise.” And now, don’t forgot: If I die before you, my will is the impossible. -

The Economic Costs of the Israeli Occupation for the Palestinian People: the Impoverishment of Gaza Under Blockade

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT The Economic Costs of the Israeli Occupation for the Palestinian People: The Impoverishment of Gaza under Blockade The Economic Costs of the Israeli Occupation for the Palestinian People: The Impoverishment of Gaza under Blockade UNITED NATIONS Geneva, 2020 © 2020, United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. United Nations Publications 405 East 42nd Street, New York, New York 10017 United States of America Email: [email protected] Website: shop.un.org The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States. The designations employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. United Nations publication issued by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. UNCTAD/GDS/APP/2020/1 ISBN: 978-92-1-112990-8 eISBN: 978-92-1-005262-7 Sales No. E.20.II.D.28 Note This study was prepared by the UNCTAD secretariat, drawing on research prepared by UNCTAD consultant Mr. Jean-Louis Arcand, Professor, International Economics, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva. The study seeks to stimulate debate on the research topic. The term “dollars” ($) refers to United States dollars. -

The First Draft: Deja Vu

Internet News Record 27/07/09 - 28/07/09 LibertyNewsprint.com U.S. Edition The First Draft: Deja vu - it’s China EU to renew US bank and healthcare again scrutiny deal By Deborah Charles (Front Row (BBC News | Americas | World terrorism investigators first came to Washington) Edition) light in 2006. The data-sharing agreement was struck in 2007 after Submitted at 7/28/2009 6:04:13 AM Submitted at 7/28/2009 3:04:02 AM European data protection authorities Presidents are never afraid of The EU plans to renew an demanded guarantees that European beating the same drum twice. agreement allowing US officials to privacy laws would not be violated. Today, President Barack Obama scrutinise European citizens' banking Speaking on Monday, EU Justice continues his quest to boost support activities under US anti-terrorism Commissioner Jacques Barrot said "it for healthcare reform with a “tele- laws. would be extremely dangerous at this town hall” at AARP. Then he talks EU member states have agreed to stage to stop the surveillance and the about relations with China, just like let the European Commission monitoring of information flows". on Monday. negotiate new conditions under A senior member of Germany's With Obama’s drive for healthcare which the US will get access to ruling Christian Democrats (CDU), reform stalled in the Senate and the private banking data. Wolfgang Bosbach, said any new House — even though both chambers US officials currently monitor agreement had to provide "certainty are controlled by his fellow transactions handled by Swift, a huge about data protection and ensure that Democrats — the president is inter-bank network based in the personal data of respectable looking to ordinary Americans to Belgium. -

European Involvement in the Arab-Israeli Conflict

EUROPEAN INVOLVEMENT IN THE ARAB-ISRAELI CONFLICT Edited by Esra Bulut Aymat Chaillot Papers | December 2010 124 In January 2002 the Institute for Security Studies (EUISS) became an autonomous Paris-based agency of the European Union. Following an EU Council Joint Action of 20 July 2001, modified by the Joint Action of 21 December 2006, it is now an integral part of the new structures that will support the further development of the CFSP/CSDP. The Institute’s core mission is to provide analyses and recommendations that can be of use and relevance to the formulation of the European security and defence policy. In carrying out that mission, it also acts as an interface between European experts and decision-makers at all levels. Chaillot Papers are monographs on topical questions written either by a member of the EUISS research team or by outside authors chosen and commissioned by the Institute. Early drafts are normally discussed at a seminar or study group of experts convened by the Institute and publication indicates that the paper is considered by the EUISS as a useful and authoritative contribution to the debate on CFSP/CSDP. Responsibility for the views expressed in them lies exclusively with authors. Chaillot Papers are also accessible via the Institute’s website: www.iss.europa.eu EUROPEAN INVOLVEMENT IN THE ARAB-ISRAELI CONFLICT Muriel Asseburg, Michael Bauer, Agnès Bertrand-Sanz, Esra Bulut Aymat, Jeroen Gunning, Christian-Peter Hanelt, Rosemary Hollis, Daniel Möckli, Michelle Pace, Nathalie Tocci Edited by Esra Bulut Aymat CHAILLOT PAPERS December 2010 124 Acknowledgements The editor would like to thank all participants of two EU-MEPP Task Force Meetings held at the EUISS, Paris, on 30 March 2009 and 2 July 2010 and an authors’ meeting held in July 2010 for their feedback on papers and draft chapters that formed the basis of the volume. -

Tribes, Identity, and Individual Freedom in Israel

Tribes, identity, and individual freedom in Israel BY Natan SacHS AND BRIAN REEVES The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. This paper is part of a series on Imagining Israel’s Future, made possible by support from the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund. The views expressed in this report are those of its author and do not represent the views of the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund, their officers, or employees. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu Table of Contents 1 The Authors 3 Acknowlegements 5 Introduction: Freedom of divorce 7 Individual autonomy and group identity 9 The four (or more) tribes of Israel 12 Institutionalizing difference 14 Secularism and religiosity 16 Conclusion 18 The Center for Middle East Policy 1 | Tribes, identity, and individual freedom in Israel The Authors atan Sachs is a fellow in the Center for rian Reeves is a senior research assistant Middle East Policy at Brookings. His at the Center for Middle East Policy at work focuses on Israeli foreign policy, do- Brookings. His work focuses primarily on Nmestic politics, the Arab-Israeli conflict, and U.S.- Bthe Israeli-Palestinian dispute, American Jewish Israeli relations. He is currently writing a book on thought pertaining to Israel, and the U.S.-Israel re- Israeli grand strategy and its domestic origins. -

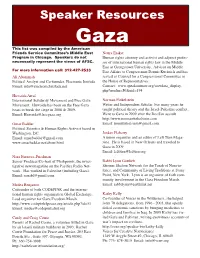

Gaza Speaker Resources.Pdf

Speaker Resources Gaza This list was compiled by the American Friends Service Committee’s Middle East Noura Erakat Program in Chicago. Speakers do not Human rights attorney and activist and adjunct profes- necessarily represent the views of AFSC. sor of international human rights law in the Middle East at Georgetown University. Advisor on Middle For more information call: 312-427-2533 East Affairs to Congressman Dennis Kucinich and has Ali Abunimah served as Counsel for a Congressional Committee in Political Analyst and Co-founder, Electronic Intifada the House of Representatives. Email: [email protected] Contact: www.speakoutnow.org/userdata_display. php?modin=50&uid=194 Huwaida Arraf International Solidarity Movement and Free Gaza Norman Finkelstein Movement. Huwaida has been on the Free Gaza Writer and Independent Scholar. For many years he boats to break the siege in 2008 & 2009. taught political theory and the Israel-Palestine conflict. Email: [email protected] Went to Gaza in 2009 after the Dec/Jan assault. http://www.normanfinkelstein.com Omar Baddar Email: [email protected] Political Scientist & Human Rights Activist based in Washington, DC. Jordan Flaherty Email: [email protected] A union organizer and an editor of Left Turn Maga- www.omarbaddar.net/about.html zine. He is based in New Orleans and traveled to Gaza in 2009. Email: [email protected] Nora Barrows-Friedman Senior Producer/Co-host of Flashpoints, the inves- Rabbi Lynn Gottlieb tigative newsmagazine on the Pacifica Radio Net- Shomer Shalom Network for the Torah of Nonvio- work. Has worked in Palestine (including Gaza). lence, and Community of Living Traditions at Stony Email: [email protected] Point, New York.