CAPSTONE 20-2 Africa Field Study Subject Page US Africa Command

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

Meta-Analysis of Travel of the Poor in West and Southern African Cities Roger Behrens, Lourdes Diaz Olvera, Didier Plat, Pascal Pochet

Meta-analysis of travel of the poor in West and Southern african cities Roger Behrens, Lourdes Diaz Olvera, Didier Plat, Pascal Pochet To cite this version: Roger Behrens, Lourdes Diaz Olvera, Didier Plat, Pascal Pochet. Meta-analysis of travel of the poor in West and Southern african cities. WCTRS, ITU. 10th World Conference on Transport Research - WCTR’04, 4-8 juillet 2004, Istanbul, Turkey, 2004, Lyon, France. pp.19 P. halshs-00087977 HAL Id: halshs-00087977 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00087977 Submitted on 8 Oct 2007 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 10th World Conference on Transport Research, Istanbul, 4-8 July 2004 META-ANALYSIS OF TRAVEL OF THE POOR IN WEST AND SOUTHERN AFRICAN CITIES Dr. Roger Behrens*, Dr. Lourdes Diaz-Olvera (corresponding author)**, Dr. Didier Plat**and Dr. Pascal Pochet** * Department of Civil Engineering, University of Cape Town, Private Bag, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa. Email: [email protected] ** Laboratoire d'Economie des Transports, ENTPE-Université Lumière Lyon 2-CNRS, rue Maurice Audin, 69518, Vaulx-en-Velin Cedex, France. Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT There have been few attempts in the past to compare travel survey findings in francophone and anglophone African countries. -

(SSA) Countries IDA19 Fourth Replenishment Meeting, December 12-13, 2019, Stockholm, Sweden

African Countries are Awakening Hope for a Better Tomorrow with IDA Statement by Representatives of 49 Sub-Saharan African (SSA) Countries IDA19 Fourth Replenishment Meeting, December 12-13, 2019, Stockholm, Sweden 1. IDA countries have only 10 years to achieve the globally agreed targets of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Given that it takes 9 years for pledges under any IDA cycle to be fully paid up, IDA19 is therefore, the last replenishment to help finance the SDGs in the time left to 2030. 2. Africa as a continent is making progress towards the SDGs. Growth in many economies has outpaced global benchmarks. More children are in school and health service coverage is expanding. A continent-wide free-trade agreement shows regional cooperation is alive and deepening, including in building roads and power lines that bring countries together and make markets bigger. The support of donors to the 18th replenishment of the International Development Association (IDA18) has been pivotal and has underpinned the partnership between African countries and the World Bank Group (WBG) that has never been stronger. Indeed, Africa’s absorptive capacity to carefully use concessional funds has ensured that the pace of commitment for IDA18 has been record-breaking. 3. We want to acknowledge the strong partnership between IDA and most of our countries. We commend all donors for the important role that IDA has been playing in the transformation agenda of most SSA countries. We are happy with the negotiated IDA19 package and the continuation of all the special themes of IDA18, the Private Sector Window, and the improvements to the various facilities especially under Fragility, Conflict and Violence (FCV). -

Understanding French Foreign and Security Policy Towards Africa: Pragmatism Or Altruism Abdurrahim Sıradağ1

Afro Eurasian Studies Journal Vol 3. Issue 1, Spring 2014 Understanding French Foreign and Security Policy towards Africa: Pragmatism or Altruism Abdurrahim Sıradağ1 Abstract France has deep economic, political and historical relations with Africa, dating back to the 17th century. Since the independence of the former colonial countries in Africa in the 1950s and 1960s, France has continued to maintain its economic and political relations with its former colonies. Importantly, France has a special strategic security partnership with the African countries. It has intervened militarily in Africa more than 50 times since 1960. France has especially continued to use its military power to strengthen its economic, political and strategic relations with Africa. For instance, it deployed its military troops in Mali in January 2013 and in the Central African Republic in December 2013. Why does France actively get involved in Africa militarily? This research will particularly uncover the main motivations behind the French foreign and security policy in Africa. Key words: Francophone Africa, France, Foreign Policy, Africa, economic interests. The Role of France in World Politics France’s international power and position has shaped its foreign and security policy towards Africa. France has been an important actor with its political and economic power in Europe and in the world. It was one of the six important founding members of the European Community after 1 International University of Sarajevo, Department of International Relations, Ilidža, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Email: [email protected] 100 the Second World War and plays a leading role in European integration. France plays a significant role in world politics through international or- ganizations. -

East and Central Africa 19

Most countries have based their long-term planning (‘vision’) documents on harnessing science, technology and innovation to development. Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twingiyimana A schoolboy studies at home using a book illuminated by a single electric LED lightbulb in July 2015. Customers pay for the solar panel that powers their LED lighting through regular instalments to M-Kopa, a Nairobi-based provider of solar-lighting systems. Payment is made using a mobile-phone money-transfer service. Photo: © Waldo Swiegers/Bloomberg via Getty Images 498 East and Central Africa 19 . East and Central Africa Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo (Republic of), Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Kenya, Rwanda, Somalia, South Sudan, Uganda Kevin Urama, Mammo Muchie and Remy Twiringiyimana Chapter 19 INTRODUCTION which invest in these technologies to take a growing share of the global oil market. This highlights the need for oil-producing Mixed economic fortunes African countries to invest in science and technology (S&T) to Most of the 16 East and Central African countries covered maintain their own competitiveness in the global market. in the present chapter are classified by the World Bank as being low-income economies. The exceptions are Half the region is ‘fragile and conflict-affected’ Cameroon, the Republic of Congo, Djibouti and the newest Other development challenges for the region include civil strife, member, South Sudan, which joined its three neighbours religious militancy and the persistence of killer diseases such in the lower middle-income category after being promoted as malaria and HIV, which sorely tax national health systems from low-income status in 2014. -

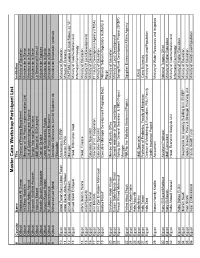

Cairo Workshop Participants

Master Cairo Workshop Participant List # Country Name Title Institution 1 Djibouti Abdourazak Ali Osman Director of Planning Department Ministry of Education 2 Djibouti Ali Sillaye Abdallah Manager of the Project Implementation Unit Ministere de la Sante 3 Djibouti Ammar Abdou Ahmed Dri. of Epidemiology and Hygiene Ministere de la Sante 4 Djibouti Assoweh Abdillahi Assoweh Service Information Sanitaire Ministere de la Sante 5 Djibouti Fatouma Bakard M&E Specialist, SIDA project Le Secretariat Executif 6 Djibouti Housein Doualeh Aboubaker Chef de Service Ministere de Finances 7 Djibouti Hussein Kayad Halane Unite de Gestion de Projets Ministere de la Sante 8 Djibouti M. Abdelrahmane Dir. of Planning and Research Ministere de la Sante 9 Djibouti Mohamed Issé Mahdi Secrétaire Générale du Comité Supérieur de Ministère de l'éducation nationale l'Education 10 Egypt Abdel Fattah Samir Abdel Fattah Accountant, ECEEP Ministry of Education 11 Egypt Abdel Samie Abdel Hafeez Director PPMU Ministry of Economy 12 Egypt Ahmed Abdel Monem Manager PAPFAM, League of Arab States, 22 "A" 13 Egypt Ahmed Saad El Sayed Head, Information Dept. Ministry of Communication and InformationTechnology: 14 Egypt Alfons Ibrahim Hanna Head, Finance Ministry of Education 15 Egypt Amal Sayed Ali Ministry Of Local Development 16 Egypt Amany Kamel Education Specialist Ministry of Education 17 Egypt Amr Mostafa Director of Int. Cooperation IT Industry Development Agency (ITIDA) 18 Egypt Amr Zein El-Abdein Mahmoud Education Specialist Ministry of Education 19 Egypt Bodour Nassif Executive Manager Development Programs Dept. National Telecom Regulatory Authority in Egypt 20 Egypt Ebraheem Abdel Khalek Member of Quality Office Ministry of Education 21 Egypt Essam Galal Hassan Shaat General manager of local monitoring Ministry of Local Development 22 Egypt Farouk Ahmed Mahmoud Sohag Gov. -

8.. Colonialism in the Horn of Africa

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The state, the crisis of state institutions and refugee migration in the Horn of Africa : the cases of Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia Degu, W.A. Publication date 2002 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Degu, W. A. (2002). The state, the crisis of state institutions and refugee migration in the Horn of Africa : the cases of Ethiopia, Sudan and Somalia. Thela Thesis. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 8.. COLONIALISM IN THE HORN OF AFRICA 'Perhapss there is no other continent in the world where colonialism showed its face in suchh a cruel and brutal form as it did in Africa. Under colonialism the people of Africa sufferedd immensely. -

Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Cities of Mali

Page 1 Policies for sustainable mobility and accessibility in cities of Mali Page 2 ¾ SSATP – Mali - Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Urban Areas – October 2019 Page 3 ¾ SSATP – Mali - Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Urban Areas – October 2019 Policies for sustainable mobility and accessibility in urban areas of Mali An international partnership supported by: Page 4 ¾ SSATP – Mali - Policies for Sustainable Mobility and Accessibility in Urban Areas – October 2019 The SSATP is an international partnership to facilitate policy development and related capacity building in the transport sector in Africa. Sound policies lead to safe, reliable, and cost-effective transport, freeing people to lift themselves out of poverty and helping countries to compete internationally. * * * * * * * The SSATP is a partnership of 42 African countries: Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Cape Verde, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, Djibouti, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, South Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe; 8 Regional Economic Communities (RECs); 2 African institutions: African Union Commission (AUC) and United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA); Financing partners for the Third Development Plan: European Commission (main donor), -

ERITREA Mahmoud Ahmed Chehem (M), Aged 21, Army Soldier Estifanos Solomon (M), Army Driver Two Male Army Officers (Names Not Known)

PUBLIC AI Index: AFR 64/001/2005 07 January 2005 UA 03/05 Forcible return / Fear of torture or ill-treatment / Detention without charge or trial ERITREA Mahmoud Ahmed Chehem (m), aged 21, army soldier Estifanos Solomon (m), army driver Two male army officers (names not known) Mahmoud Ahmed Chehem, Estifanos Solomon and two army officers were reportedly forcibly returned from Djibouti to Eritrea on 28 December 2004. They are being detained without charge at an unknown location and are at risk of torture or ill-treatment. Mahmoud Ahmed Chehem is a member of the Afar ethnic group which inhabits areas in both Djibouti and Eritrea. He was born in Djibouti, although his family live in Eritrea. On 26 December he and the three other men drove from the southwest Eritrean town of Assab to Obock town in Djibouti, where they were detained by the Djiboutian army. Mahmoud Ahmed Chehem was refused permission to stay in Djibouti, despite being a Djiboutian citizen. The three other men reportedly requested asylum in Djibouti but were summarily handed over to Eritrean military officers on 28 December, who forcibly returned them to Eritrea the same day. The three were denied the right to have their asylum application properly determined or to contact the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) office in Djibouti. Mahmoud Ahmed Chehem was unlawfully conscripted into the Eritrean army as a child soldier in 1997 when he was 14 years old. He had unsuccessfully applied recently to be demobilized on medical grounds after receiving eye injuries and shrapnel wounds during the 1998-2000 war with Ethiopia. -

Manifesto 2030 Advocacy Hub Report

Streets for Life Love30 SAFE AND HEALTHY STREETS FOR CHILDREN, YOUTH AND CLIMATE ADVOCACY HUB SUPPORT STREETS FOR LIFE Road traffic crashes are the leading cause of death At the heart of the 2020 Stockholm Declaration for children and young adults. We need a new for Global Road Safety was a call for 30 kilometre SUPPORT STREETS FOR LIFE... vision for creating safe, healthy, green and liveable cities. an hour speed limits on urban streets. Why? Because Low speed streets are an important part of that vision. we know that above 30 the risk of death for pedestrians Evidence shows that limiting driving speeds rises exponentially. So, it is a simple equation. If you to 30km/h or 20mph in cities significantly support Vision Zero, if you believe that no one should reduces road traffic deaths and injuries. As die or be maimed in a road we recover and rebuild from COVID-19, crash, then you must ‘love 30’. let’s make safer roads for a safer world. Rt. Hon. Lord Robertson of Port Ellen Dr Tedros Adhanom Chairman, FIA Ghebreyesus Foundation Director General, World Health Organization Implementing 30km/h in streets with mixed traffic, So many of us around the world are taking to and where children live, walk and play, is life-saving. the streets and demanding change. The streets Lower speeds can encourage more walking and cycling are for the people. We want low speeds, we want and help us shift to zero carbon mobility. Streets for Life liveable streets, and communities where Streets for Life contribute to achieving Love30 we can walk safely, where our children many of our Sustainable can get to school unharmed. -

Mrs. Amina Mohamed Cabinet Secretary of Education Kenya Email

Mrs. Amina Mohamed Cabinet Secretary of Education Kenya Email: [email protected] File Reference: RP/SV Contact: [email protected] 21 May 2018 Your Excellency, LACK OF SOCIAL DIALOGUE IN KENYA Public Services International (PSI) brings together more than 20 million workers, represented by over 700 unions in 163 countries and territories. We are a global trade union federation dedicated to promoting quality public services in every part of the world. Our members, two-thirds of whom are women, work in social services, health care, municipal and community services, central government, and public utilities such as water, electricity and education. PSI observes a worrying trend in Kenya in relation to the Government’s capacity to encourage industrial democracy, harmony and declining to address emerging industrial issues raised by unions. In February 2017, we already addressed a letter to the Cabinet of Health in relation to the doctors’ and nurses’ strike. On Friday 2nd March 2018, the Kenya Universities Staff Union (KUSU), called its members to withdraw labour in a national strike against the government and 31 public university managements for failing to negotiate collective bargaining covering the 2017-2021 cycle. This is the result of months of fruitless meetings without any concrete outcome. We further observe that the Government of Kenya, through its various agencies, has not availed of the instruments put in place by labour legislation to amicably address and improve emerging union concerns before they snowball into a crisis. It is important to note that long strikes are not only detrimental to harmonious working relations but also for the economy at large. -

NER N3051 4.Pdf

Hamani Diori President of the Council of Ministers of the Republic of the Niger Bornbeganin his1916careerin Niger,as a teacher.Hamani InDiori1952graduatedhe becamefromthetheprincipalEcole ofNormalea schoolin inDakarNiamey.and In 1946,he founded the Niger Progressive Party (P. P. N. ), local division of the African Democratic Rally (R.D.A.). Mr. Diori served as Deputy from Niger to the French National Assembly from 1946 to 1951, and again from 1956 to 1958. He became Vice President of that Assembly on June 21, 1957 and remained in that post until December 1958. In March 1958, Mr. Diori was a member of the French Delegation to the European Parliamentary Assembly. When, on December 18, 1958, Niger chose the status of self-governing Republic and member State of the Community, Mr. Diori became President of the Provisional Government. Following adoption of the Niger's Constitution on February 25, 1959 by the Constituent Assembly, the Republic of the Niger formed its first Government and Mr. Diori was con¬ firmed as President of the Council of Ministers. (o M - H Zg TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE The Republic of the Niger 3 Highlights of History and Recent Political Evolution 6 The Land and the People 8 Social and Cultural Development 13 Education 13 Public Health 16 Social Legislation 17 The Economy 18 Cash Crops 21 Stock Raising 24 Industry 28 Transportation 29 Foreign Trade 32 rTHE REPUBLIC OF THE NIGER A Modern Democratic State In 78%the Referendumvote in favorofofSeptemberthe Constitution28, 1958,drawnthe peopleup by Generalof Niger dereturnedGaulle'sa Government, offering the Overseas Territories of the French Republic a choice between several possible statuses.