'Far out in Texas': Countercultural Sound and the Construction Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Is Austin Still Austin?

1 IS AUSTIN STILL AUSTIN? A CULTURAL ANALYSIS THROUGH SOUND John Stevens (TC 660H or TC 359T) Plan II Honors Program The University of Texas at Austin May 13, 2020 __________________________________________ Thomas Palaima Department of Classics Supervising Professor __________________________________________ Richard Brennes Athletics Second Reader 2 Abstract Author: John Stevens Title: Is Austin Still Austin? A Cultural Analysis Through Sound Supervisors: Thomas Palaima, Ph. D and Richard Brennes For the second half of the 20th century, Austin, Texas was defined by its culture and unique personality. The traits that defined the city ushered in a progressive community that was seldom found in the South. In the 1960s, much of the new and young demographic chose music as the medium to share ideas and find community. The following decades saw Austin become a mecca for live music. Austin’s changing culture became defined by the music heard in the plethora of music venues that graced the city streets. As the city recruited technology companies and developed its downtown, live music suffered. People from all over the world have moved to Austin, in part because of the unique culture and live music. The mass-migration these individuals took part in led to the downfall of the music industry in Austin. This thesis will explore the rise of music in Austin, its direct ties with culture, and the eventual loss of culture. I aim for the reader to finish this thesis and think about what direction we want the city to go in. 3 Acknowledgments Thank you to my advisor Professor Thomas Palaima and second-reader Richard Brennes for the support and valuable contributions to my research. -

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History

AASLH 2017 ANNUAL MEETING I AM History AUSTIN, TEXAS, SEPTEMBER 6-9 JoinJoin UsUs inin T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S A CONTENTS N 3 Why Come to Austin? PRE-MEETING WORKSHOPS 37 AASLH Institutional A 6 About Austin 20 Wednesday, September 6 Partners and Patrons C I 9 Featured Speakers 39 Special Thanks SESSIONS AND PROGRAMS R 11 Top 12 Reasons to Visit Austin 40 Come Early and Stay Late 22 Thursday, September 7 E 12 Meeting Highlights and Sponsors 41 Hotel and Travel 28 Friday, September 8 M 14 Schedule at a Glance 43 Registration 34 Saturday, September 9 A 16 Tours 19 Special Events AUSTIN!AUSTIN! T E a n d L O C S TA A L r H fo I S N TO IO R T Y IA C O S S A N othing can replace the opportunitiesC ontents that arise A C when you intersect with people coming together I R around common goals and interests. E M A 2 AUSTIN 2017 oted by Forbes as #1 among America’s fastest growing cities in 2016, Austin is continually redefining itself. Home of the state capital, the heart of live music, and a center for technology and innovation, its iconic slogan, “Keep Austin Weird,” embraces the individualistic spirit of an incredible city in the hill country of Texas. In Austin you’ll experience the richness in diversity of people, histories, cultures, and communities, from earliest settlement thousands of years in the past to the present day — all instrumental in the growth of one of the most unique states in the country. -

Homegrown: Austin Music Posters 1967 to 1982

Homegrown: Austin Music Posters 1967 to 1982 Alan Schaefer The opening of the Vulcan Gas Company in 1967 marked a significant turning point in the history of music, art, and underground culture in Austin, Texas. Modeled after the psychedelic ballrooms of San Francisco, the Vulcan Gas Company presented the best of local and national psychedelic rock and roll as well as the kings and queens of the blues. The primary 46 medium for advertising performances at the 47 venue was the poster, though these posters were not simple examples of commercial art with stock publicity photos and redundant designs. The Vulcan Gas Company posters — a radical body of work drawing from psychedelia, surrealism, art nouveau, old west motifs, and portraiture — established a blueprint for the modern concert poster and helped articulate the visual language of Austin’s emerging underground scenes. The Vulcan Gas Company closed its doors in the spring of 1970, but a new decade witnessed the rapid development of Austin’s music scene and the posters that promoted it. Austin’s music poster artists offered a visual narrative of the music and culture of the city, and a substantial collection of these posters has found a home at the Wittliff Collections at Texas State University. The Wittliff Collections presented Homegrown: Austin Music Posters 1967 to 1982 in its gallery in the Alkek Library in 2015. The exhibition was curated by Katie Salzmann, lead archivist at the Wittliff Collections, and Alan Schaefer, a lecturer in the Department of English Jim Franklin. New Atlantis, Lavender Hill Express, Texas Pacific, Eternal Life Corp., and Georgetown Medical Band. -

Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas

Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas BY Joshua Long 2008 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geography and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Human Geography __________________________________ Dr. Garth Andrew Myers, Chairperson __________________________________ Dr. Jane Gibson __________________________________ Dr. Brent Metz __________________________________ Dr. J. Christopher Brown __________________________________ Dr. Shannon O’Lear Date Defended: June 5, 2008. The Dissertation Committee for Joshua Long certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Weird City: Sense of Place and Creative Resistance in Austin, Texas ___________________________________ Dr. Garth Andrew Myers, Chairperson Date Approved: June 10, 2008 ii Acknowledgments This page does not begin to represent the number of people who helped with this dissertation, but there are a few who must be recognized for their contributions. Red, this dissertation might have never materialized if you hadn’t answered a random email from a KU graduate student. Thank you for all your help and continuing advice. Eddie, you revealed pieces of Austin that I had only read about in books. Thank you. Betty, thank you for providing such a fair-minded perspective on city planning in Austin. It is easy to see why so many Austinites respect you. Richard, thank you for answering all my emails. Seriously, when do you sleep? Ricky, thanks for providing a great place to crash and for being a great guide. Mycha, thanks for all the insider info and for introducing me to RARE and Mean-Eyed Chris. -

African American Resource Guide

AFRICAN AMERICAN RESOURCE GUIDE Sources of Information Relating to African Americans in Austin and Travis County Austin History Center Austin Public Library Originally Archived by Karen Riles Austin History Center Neighborhood Liaison 2016-2018 Archived by: LaToya Devezin, C.A. African American Community Archivist 2018-2020 Archived by: kYmberly Keeton, M.L.S., C.A., 2018-2020 African American Community Archivist & Librarian Shukri Shukri Bana, Graduate Student Fellow Masters in Women and Gender Studies at UT Austin Ashley Charles, Undergraduate Student Fellow Black Studies Department, University of Texas at Austin The purpose of the Austin History Center is to provide customers with information about the history and current events of Austin and Travis County by collecting, organizing, and preserving research materials and assisting in their use. INTRODUCTION The collections of the Austin History Center contain valuable materials about Austin’s African American communities, although there is much that remains to be documented. The materials in this bibliography are arranged by collection unit of the Austin History Center. Within each collection unit, items are arranged in shelf-list order. This bibliography is one in a series of updates of the original 1979 bibliography. It reflects the addition of materials to the Austin History Center based on the recommendations and donations of many generous individuals and support groups. The Austin History Center card catalog supplements the online computer catalog by providing analytical entries to information in periodicals and other materials in addition to listing collection holdings by author, title, and subject. These entries, although indexing ended in the 1990s, lead to specific articles and other information in sources that would otherwise be time-consuming to find and could be easily overlooked. -

Downtown Trinity St 3

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P 15TH ST 15TH ST 1 SAN ANTONIO ST SAN ANTONIO GUADALUPE ST GUADALUPE 14TH ST ST BRAZOS 14TH ST 2 13TH ST Waterloo Park DOWNTOWN TRINITY ST 3 Texas State BLVD SAN JACINTO Capitol Building 12TH ST 12TH ST 4 35 BRANCH ST 11TH ST 11TH ST 5 10TH ST 10TH ST Wooldridge 6 Square 9TH ST 12TH ST 9TH ST 9TH ST SAN MARCOS ST TRINITY ST 7 NECHES ST RED RIVER RED RIVER ST 8TH ST 8TH ST ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICT 8 RIO GRANDE AVE RIO GRANDE AVE 7TH ST AVE CONGRESS 7TH ST SAN ANTONIO ST SAN ANTONIO 9 COLORADO ST COLORADO GUADALUPE ST GUADALUPE ST LAVACA NUECES ST SIXTH STREET TO EAST AUSTIN 6TH ST 6TH ST MEDINA ST MEDINA ENTERTAINMENT SABINE ST ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICT DISTRICT 10 5TH ST 5TH ST Republic Brush Square WAREHOUSE BLVD SAN JACINTO Square 11 4TH ST ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICT 12 3RD ST 3RD ST 3RD ST BRAZOS ST BRAZOS Palm 13 SECOND STREET2ND ST CONVENTION Park ENTERTAINMENT CENTER SAN MARCOS ST MARCOS SAN CESAR CHAVEZ ST DISTRICT 14 TRINITY ST DRISKILL ST Lady Bird Lake 15 DAVIS ST S 1ST ST 16 Auditorium Shores Co lo ra 17 d o R RIVER ST iv CONGRESS AVE CONGRESS e r 18 BOULDER AVE EAST AVE EAST AVE RAINEY ST 35 19 RIVERSIDE DR CLERMONT AVE BARTON SPRINGS RD 20 TO SOUTH CONGRESS AVENUE ENTERTAINMENT DISTRICT 21 .5 MILE OR 10MINUTE WALK 22 DOWNTOWN RESTAURANT GUIDE KEY: B = Breakfast L = Lunch D = Dinner LN = Late Night $ = $5-14 $$ = $15-25 $$$ = $26-50 = Music MAP RESTAURANT ADDRESS PHONE WEBSITE CUISINE MAP RESTAURANT ADDRESS PHONE WEBSITE CUISINE E 14 III Forks D $$$ 111 Lavaca St. -

Nicholas K. Roland 902 E. 14Th Street, Austin, Texas 78702 (540) 808-8458 [email protected]

Nicholas K. Roland 902 E. 14th Street, Austin, Texas 78702 (540) 808-8458 [email protected] Education Ph.D., U.S. History, The University of Texas at Austin, 2017 Austin, TX Dissertation: “‘Our Worst Enemies Are in Our Midst:’ Violence in the Texas Hill Country, 1845-1881” Advisor: Dr. Jacqueline Jones B.A, History, Virginia Tech, 2007 Blacksburg, VA Focus: War, Politics, & Diplomacy Publications “Empire on Parade: Public Representations of Race at the 1936 Texas Centennial,” in Beyond the Agrarians and Erskine Caldwell: The South in 1930s America, edited by Karen Cox and Sarah Gardner. Forthcoming through LSU Press. “‘If i git home I will take care of Num Bir one:’ Murder and Memory on the Hill Country Frontier,” West Texas Historical Review 92 (December 2016). Review of Campbell, Randolph, A Southern Community in Crisis: Harrison County, Texas, 1850-1880, for Civil War Book Review, Spring 2017, http://www.cwbr.com. Review of Glasrud, Bruce, Anti-Black Violence in Twentieth-Century Texas, in West Texas Historical Review 92 (December 2016). “Scholz Garten,” July 14, 2016, Handbook of Texas Online, Texas State Historical Association, https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/xds12. “Reconstruction in Austin: The Unknown Soldiers,” May 30, 2016, Not Even Past, https://notevenpast.org/reconstruction-in-austin-the-unknown-soldiers/. Review of Calore, Paul, The Texas Revolution and the U.S.-Mexican War: A Concise History, for H-War, H-Net Reviews (October 2015), http://www.h- net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=44303. Review of The Better Angels, in The American Historian (November 2014). “The Holland Family: An American Story,” September 29, 2014, Not Even Past, https://notevenpast.org/the-holland-family-an-american-story/. -

Arts and Entertainment Guide (Pdf) Download

ART MUSIC CULTURE Greater Austin & ENTERTAINMENTARTS Independence Title Explore www.IndependenceTitle.com “I didn't come here and I ain't leavin'. ” -Willie Nelson Austin’s artistic side is alive and well. including Austin Lyric Opera, Ballet institution serving up musical theater We are a creative community of Austin, and the Austin Symphony, as under the stars, celebrated its 50th designers, painters, sculptors, dancers, well as a rich local tradition of innovative anniversary in 2008. The Texas Film filmmakers, musicians . artists of all and avant-guarde theater groups. Commission is headquartered in Austin, kinds. And Austin is as much our and increasingly the city is being identity as it is our home. Austin is a creative community with a utilized as a favorite film location. The burgeoning circle of live performance city hosts several film festivals, The venues for experiencing art in theater venues, including the Long including the famed SXSW Film Festival Austin are very diverse. The nation's Center for the Performing Arts, held every Spring. Get out and about largest university-owned collection is Paramount Theatre, Zachary Scott and explore! exhibited at the Blanton Museum, and Theatre Center, Vortex Repertory you can view up-and-coming talent in Company, Salvage Vanguard Theater, our more intimate gallery settings. Scottish Rite Children's Theater, Hyde Austin boasts several world-renowned Park Theatre, and Esther's Follies. The classical performing arts organizations, Zilker Summer Musical, an Austin Performing Arts Choir A -

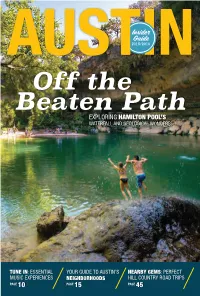

Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL and GEOLOGICAL WONDERS

Iid Guide AUSTIN2015/2016 Off the Beaten Path EXPLORING HAMILTON POOL’S WATERFALL AND GEOLOGICAL WONDERS TUNE IN: ESSENTIAL YOUR GUIDE TO AUSTIN’S NEARBY GEMS: PERFECT MUSIC EXPERIENCES NEIGHBORHOODS HILL COUNTRY ROAD TRIPS PAGE 10 PAGE 15 PAGE 45 WE DITCHED THE LANDSCAPES FOR MORE SOUNDSCAPES. If you’re going to spend some time in Austin, shouldn’t you stay in a suite that feels like it’s actually in Austin? EXPLORE OUR REINVENTION at Radisson.com/AustinTX AUSTIN CONVENTION & VISITORS BUREAU 111 Congress Ave., Suite 700, Austin, TX 78701 800-926-2282, Fax: 512-583-7282, www.austintexas.org President & CEO Robert M. Lander Vice President & Chief Marketing Officer Julie Chase Director of Marketing Communications Jennifer Walker Director of Digital Marketing Katie Cook Director of Content & Publishing Susan Richardson Director of Austin Film Commission Brian Gannon Senior Communications Manager Shilpa Bakre Tourism & PR Manager Lourdes Gomez Film, Music & Marketing Coordinator Kristen Maurel Marketing & Tourism Coordinator Rebekah Grmela AUSTIN VISITOR CENTER 602 E. Fourth St., Austin, TX 78701 866-GO-AUSTIN, 512-478-0098 Hours: Mon. – Sat. 9 a.m. – 5 p.m., Sun. 10 a.m.– 5 p.m. Director of Retail and Visitor Services Cheri Winterrowd Visitor Center Staff Erin Bevins, Harrison Eppright, Tracy Flynn, Patsy Stephenson, Spencer Streetman, Cynthia Trenckmann PUBLISHED BY MILES www.milespartnership.com Sales Office: P.O. Box 42253, Austin, TX 78704 512-432-5470, Fax: 512-857-0137 National Sales: 303-867-8236 Corporate Office: 800-303-9328 PUBLICATION TEAM Account Director Rachael Root Publication Editor Lisa Blake Art Director Kelly Ruhland Ad & Data Manager Hanna Berglund Account Executives Daja Gegen, Susan Richardson Contributing Writers Amy Gabriel, Laura Mier, Kelly Stocker SUPPORT AND LEADERSHIP Chief Executive Officer/President Roger Miles Chief Financial Officer Dianne Gates Chief Operating Officer David Burgess For advertising inquiries, please contact Daja Gegen at [email protected]. -

Good Evening, and Welcome on Behalf of Crossroads Cultural Center

Forward Together? A discussion on what the presidential campaign is revealing about the state of the American soul Speakers: Msgr. Lorenzo ALBACETE—Theologian, Author, Columnist Mr. Hendrik HERTZBERG—Executive Editor of The New Yorker Dr. Marvin OLASKY—Editor of World, Provost, The King‘s College Wednesday, March 12, 2008 at 7:00 PM, Columbia University, New York, NY Simmonds: Good evening, and welcome on behalf of Crossroads Cultural Center. Before we let Monsignor Albacete introduce our guests, we would like to explain very briefly what motivated us to organize tonight's discussion. Obviously, nowadays there is no lack of debate about the presidential elections. As should be expected, much of this debate focuses on the most current developments regarding the candidates, their policy proposals, shifts in the electorate, political alliances etc. All these are very interesting topics, of course, and are abundantly covered by the media. We felt, however, that it might be interesting to take a step back and try to ask some more general questions that are less frequently discussed, perhaps because they are harder to bring into focus and because they require more systematic reflection than is allowed by the regular news cycle. Given that politics is an important form of cultural expression, we would like to ask: What does the 2008 campaign say, if anything, about our culture? What do the candidates reveal, if anything, about our collective self-awareness and the way it is changing? Another way to ask essentially the same question is: What are the ideals that move people in America in 2008? Historically, great political movements have cultural and philosophical roots that go much deeper than politics in a strict sense. -

Home with the Armadillo

Mellard: Home with the Armadillo Home with the Armadillo: Public Memory and Performance in the 1970s Austin Music Scene Jason Dean Mellard 8 Produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2010 1 Greezy Wheels performing at the Armadillo World Headquarters. Photo courtesy of the South Austin Popular Culture Center. Journal of Texas Music History, Vol. 10 [2010], Iss. 1, Art. 3 “I wanna go home with the Armadillo Good country music from Amarillo and Abilene The friendliest people and the prettiest women You’ve ever seen.” These lyrics from Gary P. Nunn’s “London Homesick Blues” adorn the wall above the exit from the Austin Bergstrom International Airport baggage claim. For years, they also played as the theme to the award-winning PBS series Austin City Limits. In short, they have served in more than one instance as an advertisement for the city’s sense of self, the face that Austin, Texas, presents to visitors and national audiences. The quoted words refer, if obliquely, to a moment in 9 the 1970s when the city first began fashioning itself as a key American site of musical production, one invested with a combination of talent and tradition and tolerance that would make of it the self-proclaimed “Live Music Capital of the World.”1 In many ways, the venue of the Armadillo World Headquarters served as ground zero for these developments, and it is often remembered as a primary site for the decade’s supposed melding of Anglo-Texan traditions and countercultural lifestyles.2 This strand of public memory reveres the Armadillo as a place in which -

Austin's Progressive Country Music Scene and the Negotiation

Space, Place, and Protest: Austin’s Progressive Country Music Scene and the Negotiation of Texan Identities, 1968-1978 Travis David Stimeling A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Jocelyn R. Neal, Chair Jon W. Finson David García Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer © 2007 Travis David Stimeling ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT TRAVIS DAVID STIMELING: “Space, Place, and Protest: Austin’s Progressive Country Music Scene and the Negotiation of Texan Identities, 1968-1978” (Under the direction of Jocelyn R. Neal) The progressive country music movement developed in Austin, Texas, during the early 1970s as a community of liberal young musicians and concertgoers with strong interests in Texan country music traditions and contemporary rock music converged on the city. Children of the Cold War and the post-World War II migration to the suburbs, these “cosmic cowboys” sought to get back in touch with their rural roots and to leave behind the socially conservative world their parents had created for them. As a hybrid of country music and rock, progressive country music both encapsulated the contradictions of the cosmic cowboys in song and helped to create a musical sanctuary in which these youths could articulate their difference from mainstream Texan culture. Examining the work of the movement’s singer-songwriters (Michael Murphey, Guy Clark, Gary P. Nunn), western swing revivalists (Asleep at the Wheel, Alvin Crow and the Pleasant Valley Boys), and commercial country singers (Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings), this dissertation explores the proliferation of stock imagery, landscape painting, and Texan stereotypes in progressive country music and their role in the construction of Austin’s difference.