Blind Gestures: Chaplin, Diderot, Lessing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Events Brochure

1 THE EXCLUSIVE WORLD OF CHAPLIN FOR YOUR EVENTS 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENT 5 12 26 Chaplin is back Backstage Easy Street & The Circus 6 14 28 Infinite possibilities The Manoir: A space rich with emotion Hollywood Boulevard 9 22 30 A site covering 4 hectares Le Studio Restaurant: The Tramp 10 24 35 Welcome to Chaplin’s World ! The Cinema Practical information 36 Contact 4 5 CHAPLIN’S CHAPLIN WORLD IS BACK CHAPLIN’S WORLD ABSOLUTELY UNIQUE Immerse yourself in the universe of Charlie Chaplin and experience the emotion of encountering one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. harlie Chaplin is a legend, known and entertaining museum designed to plunge you Cloved all over the planet. His positive aura into the private and Hollywood life of Charlie continues to shine on the world – the very Chaplin, allowing you to discover both the man world he portrayed through his comic and and the artist: Charlie and the Tramp. Play human vision. The Tramp, his iconic character, among sets from his movies and make one of has brought, and continues to bring laughter the most beautiful spots in the Riviera your own to millions of people. Situated between lake private paradise. and mountain, Chaplin’s World By Grévin is an 6 7 INFINITE POSSIBILITIES haplin’s World By Grévin offers the PRESTIGIOUS SPACES AT THE HEART OF Crental of the entire site or certain A UNIQUE CULTURAL DESTINATION FOR: areas for the organization of private receptions, events, and activities for PROFESSIONAL EVENTS INCLUDING individuals and companies. These events Presentations and assemblies can be paired with museum visits. -

Doctor Strangelove

A PPENDI C ES Feature Film Study: Doctor Strangelove Doctor Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. Dir. Stanley Kubrick, USA, 1964. Comedy/Satire. Classification PG. 95 min. DVD, Columbia. Historical Themes/Topics War and peace in the 20th century: Cold War, nuclear arms race, atomic energy, social values and climate of 1960s Historical Context According to many historians, rapid advances in science and technology during the 20th century have contributed to making it one of the most destructive eras in world history. Arguably, in a bare-bones approach, history can be characterized as a continuing series of violent attacks between groups of humans. Typically, war is studied in terms of geographic and political realignments. However, something happened to warfare in the 20th century that has changed our collective understanding of war and peace in western societ y. The ability to understand and harness atomic energy is characteristic of the advancements in science and technology in the 20th century. It reflects the attempt among modern scientists to understand the smallest particles that are the building blocks of matter, whether in particle physics, microbiology, genetic research, or the development of the microchip. The development of the atomic bomb allowed humans to develop weapons of mass destruction. For the first time in history, human beings have the power to wipe out entire civilizations in seconds. At the same time, the increasing destructiveness of warfare is communicated with immediacy using modern Doctor Strangelove 133 communications technologies. The fact that mass communications include real images of real people suffering has played a role in developing a modern sensibility of the “other.” Faced with images of the destruction of Nagasaki and Hiroshima, North Americans saw children and families as well as whole neighbourhoods destroyed in the blink of an eye. -

PDF of the Princess Bride

THE PRINCESS BRIDE S. Morgenstern's Classic Tale of True Love and High Adventure The 'good parts' version abridged by WILLIAM GOLDMAN one two three four five six seven eight map For Hiram Haydn THE PRINCESS BRIDE This is my favorite book in all the world, though I have never read it. How is such a thing possible? I'll do my best to explain. As a child, I had simply no interest in books. I hated reading, I was very bad at it, and besides, how could you take the time to read when there were games that shrieked for playing? Basketball, baseball, marbles—I could never get enough. I wasn't even good at them, but give me a football and an empty playground and I could invent last-second triumphs that would bring tears to your eyes. School was torture. Miss Roginski, who was my teacher for the third through fifth grades, would have meeting after meeting with my mother. "I don't feel Billy is perhaps extending himself quite as much as he might." Or, "When we test him, Billy does really exceptionally well, considering his class standing." Or, most often, "I don't know, Mrs. Goldman; what are we going to do about Billy?" What are we going to do about Billy? That was the phrase that haunted me those first ten years. I pretended not to care, but secretly I was petrified. Everyone and everything was passing me by. I had no real friends, no single person who shared an equal interest in all games. -

Tonight’S Documentary About John’S Late Father, Arthur Rubinstein, Airing in PBS’ "American Masters” Series

TV SPOTS Remembering Rubinstein For some children, getting to know their father — if it happens at all — comes through honest conversation. For actor John Rubinstein, it came through watching his late father play the piano, which he says provided "an absolutely pure knowledge of a person’s soul.” It’s one of the many insights in tonight’s documentary about John’s late father, Arthur Rubinstein, airing in PBS’ "American Masters” series. Much of "Rubinstein Remembers” (WNET / 13 at 9; WLIW121 Friday at 9) spins off a visit made by the Rubinstein family earlier this year to Lodz, Poland, which was Arthur’s birthplace. With the aid of John’s narration, old photos and film clips take viewers through Arthur’s early years as John Rubinstein a musical prodigy, his Paris playboy days where his buddies were Picasso and Cocteau, his points of despair, and his years of world preeminence. There’s also footage of Arthur talking in new and old clips, and illustrating his remarks on the keyboard. Next month, "American Masters” will repeat the three "Unknown Chaplin” programs, an acclaimed analysis of Charlie Chaplin’s career that included previously unseen footage of the silent-film comedian. The shows hagin Aug. 3. Other August programs will spotligm George Gershwin and Maurice SanAtk Tonight 9:00 PM ® CD AMERICAN MASTERS. “Ru binstein Remembered: A 100th Anniversary Tri bute." Classical pianist Arthur Rubinstein (photo right) is given a loving tribute by his son, actor and musician John Rubinstein (photo). Filmed in part in Lodz, Poland, Rubinstein’s birthplace. Also shown on ® Friday at 9 pm (60 min.). -

Letting the Other In, Queering the Nation

Letting the Other in, Queering the Nation: Bollywood and the Mimicking Body Ronie Parciack Tel Aviv University Bombay’s film industry, Bollywood, is an arena that is represented and generated by the medium as a male intensively transmits cultural products from one na - homosexual body. tionality to another; it is a mimicking arena that in - cessantly appropriates narratives of Western Culture, particularly from Hollywood. Hence its nick-name Bollywood and the work of mimicry that contains the transcultural move back and forth Bollywood, Mumbai’s cinematic industry, is an inten - between and Bombay/Mumbai, all the while retain - sive arena absorbing foreign cultural products, mainly ing the ambivalent space positioned betwixt and be - Western. Characters, cultural icons, genres, lifestyle tween, and the unsteady cultural boundaries derived accoutrements such as clothing, furnishing, recreation from the postcolonial situation. styles, western pop songs and entire cinematic texts This paper examines the manner in which this have constantly been appropriated and adapted dur - transcultural move takes place within the discourse of ing decades of film-making. gender; namely, how the mimicking strategy forms a The mimicry phenomenon, with its central locus body and provides it with an ambiguous sexual iden - in the colonial situation and the meanings it contin - tity. My discussion focuses on the film Yaraana ues to incorporate in the postcolonial context, is a (David Dhawan, 1995) – a Bollywood adaptation of loaded focus in current discourse on globalization and Sleeping with the Enemy (Joseph Ruben, 1989). The localization, homogenization and heterogenization. Hollywood story of a woman who flees a violent hus - This paper examines the way in which the mimicking band exists in the Bollywood version, but takes on a deed can highlight the gendered layout of the mim - minor role compared to its narrative focus: an (insin - icking arena. -

Film Essay for "Modern Times"

Modern Times By Jeffrey Vance No human being is more responsible for cinema’s ascendance as the domi- nant form of art and entertainment in the twentieth century than Charles Chaplin. Yet, Chaplin’s importance as a historic figure is eclipsed only by his creation, the Little Tramp, who be- came an iconic figure in world cinema and culture. Chaplin translated tradi- tional theatrical forms into an emerg- ing medium and changed both cinema and culture in the process. Modern screen comedy began the moment Chaplin donned his derby hat, affixed his toothbrush moustache, and Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp character finds he has become a cog in the stepped into his impossibly large wheels of industry. Courtesy Library of Congress Collection. shoes for the first time. “Modern Times” is Chaplin’s self-conscious subjects such as strikes, riots, unemployment, pov- valedictory to the pantomime of silent film he had pio- erty, and the tyranny of automation. neered and nurtured into one of the great art forms of the twentieth century. Although technically a sound The opening title to the film reads, “Modern Times: a film, very little of the soundtrack to “Modern Times” story of industry, of individual enterprise, humanity contains dialogue. The soundtrack is primarily crusading in the pursuit of happiness.” At the Electro Chaplin’s own musical score and sound effects, as Steel Corporation, the Tramp is a worker on a factory well as a performance of a song by the Tramp in gib- conveyor belt. The little fellow’s early misadventures berish. This remarkable performance marks the only at the factory include being volunteered for a feeding time the Tramp ever spoke. -

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin's Influence on American

THE ANIMATED TRAMP Charlie Chaplin’s Influence on American Animation By Nancy Beiman SLIDE 1: Joe Grant trading card of Chaplin and Mickey Mouse Charles Chaplin became an international star concurrently with the birth and development of the animated cartoon. His influence on the animation medium was immense and continues to this day. I will discuss how American character animators, past and present, have been inspired by Chaplin’s work. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND (SLIDE 2) Jeffrey Vance described Chaplin as “the pioneer subject of today’s modern multimedia marketing and merchandising tactics”, 1 “(SLIDE 3). Charlie Chaplin” comic strips began in 1915 and it was a short step from comic strips to animation. (SLIDE 4) One of two animated Chaplin series was produced by Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan Studios in 1918-19. 2 Immediately after completing the Chaplin cartoons, (SLIDE 5) Otto Messmer created Felix the Cat who was, by 1925, the most popular animated character in America. Messmer, by his own admission, based Felix’s timing and distinctive pantomime acting on Chaplin’s. 3 But no other animators of the time followed Messmer’s lead. (SLIDE 6) Animator Shamus Culhane wrote that “Right through the transition from silent films to sound cartoons none of the producers of animation paid the slightest attention to… improvements in the quality of live action comedy. Trapped by the belief that animated cartoons should be a kind of moving comic strip, all the producers, (including Walt Disney) continued to turn out films that consisted of a loose story line that supported a group of slapstick gags which were often only vaguely related to the plot….The most astonishing thing is that Walt Disney took so long to decide to break the narrow confines of slapstick, because for several decades Chaplin, Lloyd and Keaton had demonstrated the superiority of good pantomime.” 4 1 Jeffrey Vance, CHAPLIN: GENIUS OF THE CINEMA, p. -

Glenn Mitchell the TRUE FAREWELL of the TRAMP

Glenn Mitchell THE TRUE FAREWELL OF THE TRAMP Good afternoon. I’d like to begin with an ending ... which we might call `the Tramp’s First Farewell’. CLIP: FINAL SCENE OF `THE TRAMP’ That, of course, was the finale to Chaplin’s 1915 short film THE TRAMP. Among Chaplin scholars – and I think there may be one or two here today! - one of the topics that often divides opinion is that concerning the first and last appearances of Chaplin’s Tramp character. It seems fair to suggest that Chaplin’s assembly of the costume for MABEL’S STRANGE PREDICAMENT marks his first appearance, even though he has money to dispose of and is therefore technically not a tramp. KID AUTO RACES AT VENICE, shot during its production, narrowly beat the film into release. Altogether more difficult is to pinpoint where Chaplin’s Tramp character appears for the last time. For many years, the general view was that the Tramp made his farewell at the end of MODERN TIMES. As everyone here will know, it was a revision of that famous conclusion to THE TRAMP, which we saw just now ... only this time he walks into the distance not alone, but with a female companion, one who’s as resourceful, and almost as resilient, as he is. CLIP: END OF `MODERN TIMES’ When I was a young collector starting out, one of the key studies of Chaplin’s work was The Films of Charlie Chaplin, published in 1965. Its authors, Gerald D. McDonald, Michael Conway and Mark Ricci said this of the end of MODERN TIMES: - No one realized it at the time, but in that moment of hopefulness we were seeing Charlie the Little Tramp for the last time. -

Lecture Outlines

21L011 The Film Experience Professor David Thorburn Lecture 1 - Introduction I. What is Film? Chemistry Novelty Manufactured object Social formation II. Think Away iPods The novelty of movement Early films and early audiences III. The Fred Ott Principle IV. Three Phases of Media Evolution Imitation Technical Advance Maturity V. "And there was Charlie" - Film as a cultural form Reference: James Agee, A Death in the Family (1957) Lecture 2 - Keaton I. The Fred Ott Principle, continued The myth of technological determinism A paradox: capitalism and the movies II. The Great Train Robbery (1903) III. The Lonedale Operator (1911) Reference: Tom Gunning, "Systematizing the Electronic Message: Narrative Form, Gender and Modernity in 'The Lonedale Operator'." In American Cinema's Transitional Era, ed. Charlie Keil and Shelley Stamp. Univ. of California Press, 1994, pp. 15-50. IV. Buster Keaton Acrobat / actor Technician / director Metaphysician / artist V. The multiplicity principle: entertainment vs. art VI. The General (1927) "A culminating text" Structure The Keaton hero: steadfast, muddling The Keaton universe: contingency Lecture 3 - Chaplin 1 I. Movies before Chaplin II. Enter Chaplin III. Chaplin's career The multiplicity principle, continued IV. The Tramp as myth V. Chaplin's world - elemental themes Lecture 4 - Chaplin 2 I. Keaton vs. Chaplin II. Three passages Cops (1922) The Gold Rush (1925) City Lights (1931) III. Modern Times (1936) Context A culminating film The gamin Sound Structure Chaplin's complexity Lecture 5 - Film as a global and cultural form I. Film as a cultural form Global vs. national cinema American vs. European cinema High culture vs. Hollywood II. -

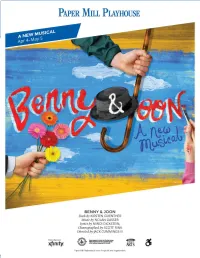

2019-BENNY-AND-JOON.Pdf

CREATIVE TEAM KIRSTEN GUENTHER (Book) is the recipient of a Richard Rodgers Award, Rockefeller Grant, Dramatists Guild Fellowship, and a Lincoln Center Honorarium. Current projects include Universal’s Heart and Souls, Measure of Success (Amanda Lipitz Productions), Mrs. Sharp (Richard Rodgers Award workshop; Playwrights Horizons, starring Jane Krakowski, dir. Michael Greif), and writing a new book to Paramount’s Roman Holiday. She wrote the book and lyrics for Little Miss Fix-it (as seen on NBC), among others. Previously, Kirsten lived in Paris, where she worked as a Paris correspondent (usatoday.com). MFA, NYU Graduate Musical Theatre Writing Program. ASCAP and Dramatists Guild. For my brother, Travis. NOLAN GASSER (Music) is a critically acclaimed composer, pianist, and musicologist—notably, the architect of Pandora Radio’s Music Genome Project. He holds a PhD in Musicology from Stanford University. His original compositions have been performed at Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, among others. Theatrical projects include the musicals Benny & Joon and Start Me Up and the opera The Secret Garden. His book, Why You Like It: The Science and Culture of Musical Taste (Macmillan), will be released on April 30, 2019, followed by his rock/world CD Border Crossing in June 2019. His TEDx Talk, “Empowering Your Musical Taste,” is available on YouTube. MINDI DICKSTEIN (Lyrics) wrote the lyrics for the Broadway musical Little Women (MTI; Ghostlight/Sh-k-boom). Benny & Joon, based on the MGM film, was a NAMT selection (2016) and had its world premiere at The Old Globe (2017). Mindi’s work has been commissioned, produced, and developed widely, including by Disney (Toy Story: The Musical), Second Stage (Snow in August), Playwrights Horizons (Steinberg Commission), ASCAP Workshop, and Lincoln Center (“Hear and Now: Contemporary Lyricists”). -

The Inside Story of the Gold Rush, by Jacques Antoine Moerenhout

The inside story of the gold rush, by Jacques Antoine Moerenhout ... translated and edited from documents in the French archives by Abraham P. Nasatir, in collaboration with George Ezra Dane who wrote the introduction and conclusion Jacques Antoine Moerenhout (From a miniature in oils on ivory, possibly a self-portrait; lent by Mrs. J.A. Rickman, his great-granddaughter.) THE INSIDE STORYTHE GOLD RUSH By JACQUES ANTOINE MOERENHOUT Consul of France at Monterey TRANSLATED AND EDITED FROM DOCUMENTS IN THE FRENCH ARCHIVES BY ABRAHAM P. NASATIR IN COLLABORATION WITH GEORGE EZRA DANE WHO WROTE THE INTRODUCTION AND CONCLUSION SPECIAL PUBLICATION NUMBER EIGHT CALIFORNIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY The inside story of the gold rush, by Jacques Antoine Moerenhout ... translated and edited from documents in the French archives by Abraham P. Nasatir, in collaboration with George Ezra Dane who wrote the introduction and conclusion http://www.loc.gov/resource/ calbk.018 SAN FRANCISCO 1935 Copyright 1935 by California Historical Society Printed by Lawton R. Kennedy, San Francisco I PREFACE THE PUBLICATION COMMlTTEE of the California Historical Society in reprinting that part of the correspondence of Jacques Antoine Moerenhout, which has to do with the conditions in California following the discovery of gold by James Wilson Marshall at Sutter's sawmill at Coloma, January 24, 1848, under the title of “The Inside Story of the Gold Rush,” wishes to acknowledge its debt to Professor Abraham P. Nasatir whose exhaustive researches among French archives brought this hitherto unpublished material to light, and to Mr. George Ezra Dane who labored long and faithfully in preparing it for publication. -

Charlie Chaplin: the Genius Behind Comedy Zuzanna Mierzejewska College of Dupage

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by [email protected]. ESSAI Volume 9 Article 28 4-1-2011 Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy Zuzanna Mierzejewska College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai Recommended Citation Mierzejewska, Zuzanna (2011) "Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy," ESSAI: Vol. 9, Article 28. Available at: http://dc.cod.edu/essai/vol9/iss1/28 This Selection is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at [email protected].. It has been accepted for inclusion in ESSAI by an authorized administrator of [email protected].. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mierzejewska: Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy Charlie Chaplin: The Genius Behind Comedy by Zuzanna Mierzejewska (English 1102) he quote, “A picture with a smile-and perhaps, a tear” (“The Kid”) is not just an introduction to Charlie Chaplin’s silent film, The Kid, but also a description of his life in a nutshell. Many Tmay not know that despite Chaplin’s success in film and comedy, he had a very rough childhood that truly affected his adult life. Unfortunately, the audience only saw the man on the screen known world-wide as the Tramp, characterized by: his clown shoes, cane, top hat and a mustache. His humor was universal; it focused on the simplicity of our daily routines and the funniness within them. His comedy was well-appreciated during the silent film era and cheered soldiers up as they longed for peace and safety during World War I and other events in history.