Low-Temperature Exotherms and Cold Hardiness in Three Taxa of Deciduous Trees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 2, Ranges for Optimal and Suboptimal Growth for Site, Climate, and Soil Variables

APPENDIX 2 Ranges for Optimal and Suboptimal Growth for Site, Climate, and Soil Variables Climate and soil data in these figures were provided by the Landscape Change Research Group (U.S. Forest Service, n.d.). Current climate parameter data are from Hayhoe et al. (2007) and are based on United States Historical Climatology network data from 1961- 1990. Soil and topographic parameter data are from STATSGO data (Soil Conservation Service 1991). For further information, see the Climate Change Atlas website: https:// www.fs.fed.us/nrs/atlas/. Optimal elevation ranges were derived from information in “Silvics of North America” (Burns and Honkala 1990), Leak and Graber (1974), Beckage et al. (2008), and other sources. Depth to bedrock (minimum rooting depth) values come from the PLANTS database (NRCS 2014). Because optimal and suboptimal ranges are not known for minimum rooting depth, arrows indicate the beginning of the range. 143 Elevation (m): range for optimal growth 0 200 400 600 800 1000 1200 1400 1600 Quercus alba Fraxinus pennsylvanica Quercus prinus Pinus strobus Castanea dentata Ulmus americana Acer rubrum Fraxinus americana Juglans cinerea Pinus rigida Quercus rubra Tsuga canadensis Fagus grandifolia Acer saccharum Populus tremuloides Thuja occidentalis Populus grandidentata Picea mariana Pinus resinosa Betula alleghaniensis Picea rubens Betula payrifera Abies balsamea Slope gradient (%): ranges for optimal and suboptimal growth 0 5 10 15 20 25 Picea mariana Thuja occidentalis Populus tremuloides Pinus resinosa Fraxinus pennsylvanica -

Recommended Trees to Plant

Recommended Trees to Plant Large Sized Trees (Mature height of more than 45') (* indicates tree form only) Trees in this category require a curb/tree lawn width that measures at least a minimum of 8 feet (area between the stree edge/curb and the sidewalk). Trees should be spaced a minimum of 40 feet apart within the curb/tree lawn. Trees in this category are not compatible with power lines and thus not recommended for planting directly below or near power lines. Norway Maple, Acer platanoides Cleveland Norway Maple, Acer platanoides 'Cleveland' Columnar Norway Maple, Acer Patanoides 'Columnare' Parkway Norway Maple, Acer Platanoides 'Columnarbroad' Superform Norway Maple, Acer platanoides 'Superform' Red Maple, Acer rubrum Bowhall Red Maple, Acer rubrum 'Bowhall' Karpick Red Maple, Acer Rubrum 'Karpick' Northwood Red Maple, Acer rubrum 'Northwood' Red Sunset Red Maple, Acer Rubrum 'Franksred' Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum Commemoration Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Commemoration' Endowment Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Endowment' Green Mountain Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Green Mountain' Majesty Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Majesty' Adirzam Sugar Maple, Acer saccharum 'Adirzam' Armstrong Freeman Maple, Acer x freemanii 'Armstrong' Celzam Freeman Maple, Acer x freemanii 'Celzam' Autumn Blaze Freeman, Acer x freemanii 'Jeffersred' Ruby Red Horsechestnut, Aesculus x carnea 'Briotii' Heritage River Birch, Betula nigra 'Heritage' *Katsura Tree, Cercidiphyllum japonicum *Turkish Filbert/Hazel, Corylus colurna Hardy Rubber Tree, Eucommia ulmoides -

Boron in Wood Preservation: Problems, Challenges and Proposed Solutions

BORON IN WOOD PRESERVATION: PROBLEMS, CHALLENGES AND PROPOSED SOLUTIONS. AN OVERVIEW ON RECENT RESEARCH Fernando Caldeira Jorge - Fernando Pessoa University, Faculty of Science and Technology Centre for Modelling and Analysis of Environmental Systems (CEMAS) Associate Professor | E-mail: [email protected] Lina Nunes - National Laboratory for Civil Engineering Timber Structures Division (LNEC) Researcher | E-mail: [email protected] Cidália Botelho - Faculty of Engineering of the Oporto University, Department of Chemical Engineering Laboratory of Separation and Reaction Engineering (LSRE) Assistant Professor | E-mail: [email protected] ABSTR A CT 3 A short review is presented on boron as a wood preservative. Sessions include the kind of chemicals applied and the level of efficiency obtained against several kind of fungi and termites, the influence of wood species, the traditional problem of boron leachability if timber is simply impregnated with aqueous solutions of acid boric or borate, but that at the same time enables impregnation of less permeable wood species by slow diffusion of unseasoned timber, the application of boron in conjunction with polymer or proteins, claimed as increasing significantly the resistance to leaching, and, finally, a summary is made on the boron chemistry that can be explored for boron-in-wood fixation studies, an approach that has been already started to be followed by the authors. RESUMO É feita uma revisão sintética sobre o elemento boro como um agente preser- vador da madeira. Temas específicos incluem os tipos -

Comparative Studies of the Leaf Morphology and Structure of White Ash Fraxinus Americana L

2004, vol. 52, 3–8 Snejana B. Dineva Comparative studies of the leaf morphology and structure of white ash Fraxinus americana L. and London plane tree Platanus acerifolia Willd growing in polluted area Received: 30 April 2004, Accepted: 9 August 2004 Abstract: The leaf blades of white ash Fraxinus americana L. and London plane tree Platanus acerifolia Willd. growing in heavy polluted industrial areas were studied for morphological and anatomical changes developed under the influence of industrial contamination. The aim of the investigation was to determine and compare the influences of air polluted with SO2,NxOx, Pb, As, Zn, Cu etc. on the morphology and the structure of the leaves of these deciduous trees. Both species are tolerant to environmental changes but with different envi- ronmental characteristics and tolerances and they are widely used for planting. Under polluted conditions, the trees strengthened the anatomic xeromorphic characteristics of their leaf structures, which gave them the opportunity to mitigate the stressful conditions of the environment. The observed responses are regarded as adaptive and compensative to the adverse effects of air pollution. Additional key words: air pollution, morphology, anatomy of leaf, Fraxinus americana L., Platanus acerifolia Willd. Address: S. B. Dineva, Technical College – Yambol, Thracian University “Stara Zagora”, “Gr. Ignatiev” No. 38 str., Yambol 8600, Bulgaria, e-mail: [email protected] Introduction 1988; Bhatti and Iqbal 1988; Veselkin 2004). Plant adaptation to changing environmental factors in- Environmental conditions, including polluted air, volves both short-term physiological responses and water, soil etc., place trees under numerous stresses long-term physiological, structural, and morphologi- and contribute to their decline. -

City of Carrollton Summary of the Tree Preservation Ordinance (Ordinance 2520, As Amended by Ordinance 2622)

City of Carrollton Summary of the Tree Preservation Ordinance (Ordinance 2520, as amended by Ordinance 2622) A. Application & Exemptions 1. Ordinance applies to all vacant, unplatted or undeveloped property; property to be re- platted or redeveloped, and; public property, whether developed or not. 2. Ordinance does not apply to individual single-family or duplex residential lots after initial development/subdivision, provided that the use of the lot remains single-family or duplex residential. 3. Ordinance does not apply to Section 404 Permits issued by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 4. Routine pruning and maintenance is permitted, provided that it does not damage the health and beauty of the protected tree. B. Protected Trees 1. Only those kinds of trees listed on the Approved Plant List which are 4" in diameter or greater are protected. C. Preservation & Replacement 1. A plan to preserve or replace protected trees must be approved by the City before development or construction, or the removal of any protected tree. The plan must be followed. If no protected trees are present, a letter to that effect, signed by a surveyor, engineer, architect or landscape architect must be submitted to the City. 2. Protected trees to be removed must be replaced. Replacement trees must be chosen from the Approved Plant List, and be of a certain minimum size. Where 12 or more are to be replaced, no more than 34% of the replacement trees may be of the same kind. Replacement trees may be planted off-site, or a fee may be paid to the City instead of replacement, if there is/are no suitable location(s) on the subject property. -

Fraxinus Spp. Family: Oleaceae American Ash

Fraxinus spp. Family: Oleaceae American Ash Ash ( Fraxinus sp.) is composed of 40 to 70 species, with 21 in Central and North America and 50 species in Eurasia. All species look alike microscopically. The name fraxinus is the classical Latin name for ash. Fraxinus americana*- American White Ash, Biltmore Ash, Biltmore White Ash, Canadian Ash, Cane Ash, Green Ash, Ground Ash, Mountain Ash, Quebec Ash, Red Ash, Smallseed White Ash, White Ash , White River Ash, White Southern Ash Fraxinus anomala-Dwarf Ash, Singleleaf Ash Fraxinus berlandierana-Berlandier Ash , Mexican Ash Fraxinus caroliniana-Carolina Ash , Florida Ash, Pop Ash, Swamp Ash, Water Ash Fraxinus cuspidata-Flowering Ash, Fragrant Ash Fraxinus dipetala-California Flwoering Ash, California Shrub Ash, Foothill Ash, Flowering Ash, Fringe- flowering Ash, Mountain Ash, Two-petal Ash Fraxinus gooddingii-Goodding Ash Fraxinus greggii-Dogleg Ash, Gregg Ash, Littleleaf Ash Fraxinus latifolia*-Basket Ash, Oregon Ash, Water Ash, White Ash Fraxinus nigra*-American Black Ash, Basket Ash, Black Ash , Brown Ash, Canadian Ash, Hoop Ash, Splinter Ash, Swamp Ash, Water Ash Fraxinus papillosa-Chihuahua Ash Fraxinus pennsylvanica*-Bastard Ash, Black Ash, Blue Ash, Brown Ash, Canadian Ash, Darlington Ash, Gray Ash, Green Ash , Piss Ash, Pumpkin Ash, Red Ash, Rim Ash, River Ash, Soft Ash,Swamp Ash, Water Ash, White Ash Fraxinus profunda*-Pumpkin Ash, Red Ash Fraxinus quadrangulata*-Blue Ash , Virginia Ash Fraxinus texensis-Texas Ash Fraxinus velutina-Arizona Ash, Desert Ash, Leatherleaf Ash, Modesto Ash, Smooth Ash, Toumey Ash, Velvet Ash (* commercial species) Distribution The north temperate regions of the globe. The Tree Ashes are trees or shrubs with large, opposite, pinnately compound leaves, which are shed in the fall. -

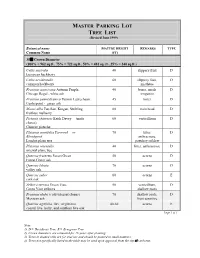

MASTER PARKING LOT TREE LIST (Revised June 1999)

MASTER PARKING LOT TREE LIST (Revised June 1999) Botanical name MATURE HEIGHT REMARKS TYPE Common Name (FT) 35 Crown Diameter (100% = 962 sq.ft., 75% = 722 sq.ft., 50% = 481 sq. ft., 25% = 240 sq.ft.) Celtis australis 40 slippery fruit D European hackberry Celtis occidentalis 60 slippery fruit, D common hackberry mistletoe Fraxinus americana Autumn Purple, 40 borer, needs D Chicago Regal - white ash irrigation Fraxinus pennsylvanica Patmor Leprechaun, 45 borer D Centerpoint - green ash Morus alba Fan-San, Kingan, Stribling 60 train head D fruitless mulberry Pistacia chinensis Keith Davey (male 60 verticillium D clones) Chinese pistache Platanus acerifolia Yarwood or 70 litter, D Bloodgood anthracnose, London plane tree powdery mildew Platanus orientalis 40 litter, anthracnose D oriental plane tree Quercus frainetto Forest Green 50 acorns D Forest Green oak Quercus lobata 70 acorns D valley oak Quercus suber 80 acorns E cork oak Zelkova serrata Green Vase 50 verticillium, D Green Vase zelkova shallow roots Fraxinus uhdei (cold-tolerant clones) 70 shallow roots, D Mexican ash frost sensitive Quercus agrifolia, ilex, virginiana 40-60 acorns E coastal live, holly, and southern live oak Page 1 of 3 Note: 1) D = Deciduous Tree; E = Evergreen Tree. 2) Crown diameters are estimated for 15-years after planting. 3) Trees in shaded cells are for trial use and should be planted in small numbers. 4) Trees not specifically listed in the table may be used upon approval from the citys arborist. Botanical name MATURE HEIGHT REMARKS TYPE Common Name (FT) 30 Crown Diameter (100% = 708 sq.ft. 75% = 531 sq.ft. -

Landscaping Near Black Walnut Trees

Selecting juglone-tolerant plants Landscaping Near Black Walnut Trees Black walnut trees (Juglans nigra) can be very attractive in the home landscape when grown as shade trees, reaching a potential height of 100 feet. The walnuts they produce are a food source for squirrels, other wildlife and people as well. However, whether a black walnut tree already exists on your property or you are considering planting one, be aware that black walnuts produce juglone. This is a natural but toxic chemical they produce to reduce competition for resources from other plants. This natural self-defense mechanism can be harmful to nearby plants causing “walnut wilt.” Having a walnut tree in your landscape, however, certainly does not mean the landscape will be barren. Not all plants are sensitive to juglone. Many trees, vines, shrubs, ground covers, annuals and perennials will grow and even thrive in close proximity to a walnut tree. Production and Effect of Juglone Toxicity Juglone, which occurs in all parts of the black walnut tree, can affect other plants by several means: Stems Through root contact Leaves Through leakage or decay in the soil Through falling and decaying leaves When rain leaches and drips juglone from leaves Nuts and hulls and branches onto plants below. Juglone is most concentrated in the buds, nut hulls and All parts of the black walnut tree produce roots and, to a lesser degree, in leaves and stems. Plants toxic juglone to varying degrees. located beneath the canopy of walnut trees are most at risk. In general, the toxic zone around a mature walnut tree is within 50 to 60 feet of the trunk, but can extend to 80 feet. -

Biodiversity and Coarse Woody Debris in Southern Forests Proceedings of the Workshop on Coarse Woody Debris in Southern Forests: Effects on Biodiversity

Biodiversity and Coarse woody Debris in Southern Forests Proceedings of the Workshop on Coarse Woody Debris in Southern Forests: Effects on Biodiversity Athens, GA - October 18-20,1993 Biodiversity and Coarse Woody Debris in Southern Forests Proceedings of the Workhop on Coarse Woody Debris in Southern Forests: Effects on Biodiversity Athens, GA October 18-20,1993 Editors: James W. McMinn, USDA Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, Athens, GA, and D.A. Crossley, Jr., University of Georgia, Athens, GA Sponsored by: U.S. Department of Energy, Savannah River Site, and the USDA Forest Service, Savannah River Forest Station, Biodiversity Program, Aiken, SC Conducted by: USDA Forest Service, Southem Research Station, Asheville, NC, and University of Georgia, Institute of Ecology, Athens, GA Preface James W. McMinn and D. A. Crossley, Jr. Conservation of biodiversity is emerging as a major goal in The effects of CWD on biodiversity depend upon the management of forest ecosystems. The implied harvesting variables, distribution, and dynamics. This objective is the conservation of a full complement of native proceedings addresses the current state of knowledge about species and communities within the forest ecosystem. the influences of CWD on the biodiversity of various Effective implementation of conservation measures will groups of biota. Research priorities are identified for future require a broader knowledge of the dimensions of studies that should provide a basis for the conservation of biodiversity, the contributions of various ecosystem biodiversity when interacting with appropriate management components to those dimensions, and the impact of techniques. management practices. We thank John Blake, USDA Forest Service, Savannah In a workshop held in Athens, GA, October 18-20, 1993, River Forest Station, for encouragement and support we focused on an ecosystem component, coarse woody throughout the workshop process. -

Evidence That Soil Aluminum Enforces Site Fidelity of Southern New England Forest Trees Author(S): Seth W

Evidence That Soil Aluminum Enforces Site Fidelity of Southern New England Forest Trees Author(s): Seth W. Bigelow and Charles D. Canham Source: Rhodora, 112(949):1-21. 2010. Published By: The New England Botanical Club, Inc. DOI: 10.3119/08-32.1 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3119/08-32.1 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is an electronic aggregator of bioscience research content, and the online home to over 160 journals and books published by not-for-profit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. RHODORA, Vol. 112, No. 949, pp. 1–21, 2010 E Copyright 2010 by the New England Botanical Club EVIDENCE THAT SOIL ALUMINUM ENFORCES SITE FIDELITY OF SOUTHERN NEW ENGLAND FOREST TREES 1,2 1 SETH W. BIGELOW AND CHARLES D. CANHAM 1Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Box AB, Millbrook, NY 12545 2USDA-FS, Pacific Southwest Research Station, 1731 Research Park Drive, Davis, CA 95618 e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Tree species composition of hardwood forests of the northeastern United States corresponds with soil chemistry, and differential performance along soil calcium (Ca) gradients has been proposed as a mechanism for enforcing this fidelity of species to site. -

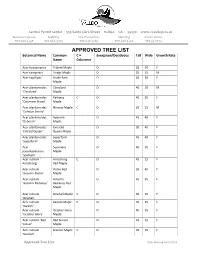

APPROVED TREE LIST Botanical Name Common C = Evergreen/Deciduous Tall Wide Growth Rate Name Columnar

Central Permit Center ∙ 555 Santa Clara Street ∙ Vallejo ∙ CA ∙ 94590 ∙ www.ci.vallejo.ca.us Business License Building Fire Prevention Planning Public Works 707.648.4357 707.648.4374 707.648.4565 707.648.4326 707.651.7151 APPROVED TREE LIST Botanical Name Common C = Evergreen/Deciduous Tall Wide Growth Rate Name Columnar Acer buergeranus Trident Maple D 25 20 F Acer campestre Hedge Maple D 25 15 M Acer capillipes Snake Bark D 40 30 F Maple Acer plantanoides Cleveland D 40 30 M 'Cleveland' Maple Acer plantanoides Parkway C D 40 25 F 'Columnar Broad' Maple Acer plantanoides Norway Maple C D 25 15 M 'Crimson Sentry' Acer plantanoides Deborah D 45 40 F 'Deborah' Maple Acer plantanoides Emerald D 50 40 F 'Emrald Queen' Queen Maple Acer plantanoides Superform D 45 40 F 'Superform' Maple Acer Sycamore D 40 30 F pseudoplatanus Maple 'Spathelli' Acer rubrum ' Armstrong C D 45 15 F Armstrong' Red Maple Acer rubrum Flame Red D 50 40 F 'Autumn Flame' Maple Acer rubrum Autumn D 45 35 F 'Autumn Radiance' Radiance Red Maple Acer rubrum Bowhall Maple C D 40 15 F 'Bowhall' Acer rubrum Karpick Maple C D 35 25 F 'Karpick' Acer rubrum October Glory D 40 35 F 'October Glory' Maple Acer rubrum 'Red Red Sunset D 45 35 F Sunset' Maple Acer rubrum Scanlon Maple C D 35 25 F 'Scanlon' Approved Tree List Date Revised 04/10/2014 APPROVED TREE LIST Botanical Name Common C = Evergreen/Deciduous Tall Wide Growth Rate Name Columnar Acer rubrum Scarlet C D 40 20 F 'Scarlet Sentinel' Sentinal Maple Acer rubrum Scarlet C D 40 30 F 'Scarlet Sentinel' Sentinel Maple Acer -

White Ash (Fraxinus Americana) Decline and Mortality: the Role of Site Nutrition and Stress History ⇑ Alejandro A

Forest Ecology and Management 286 (2012) 8–15 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco White ash (Fraxinus americana) decline and mortality: The role of site nutrition and stress history ⇑ Alejandro A. Royo a, , Kathleen S. Knight b a USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Irvine, PA 16365, USA b USDA Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Delaware, OH, USA article info abstract Article history: Over the past century, white ash (Fraxinus americana) populations throughout its range have deteriorated Received 3 August 2012 as a result of declining tree health and increased mortality rates. Although co-occurring factors including Received in revised form 30 August 2012 site nutritional deficiencies and punctuated stress events (e.g., defoliations, drought) are hypothesized to Accepted 31 August 2012 trigger white ash decline, there are no empirical assessments of these factors at regional scales. In this study, we evaluated ash crown dieback, crown health condition, and mortality on 190 plots paired along a topographic gradient known to differ in site nutrition across a 3000 km2 area of northwestern Pennsyl- Keywords: vania, USA. Additionally, we assessed white ash foliar nutrient content and additional factors including Dieback defoliation history as potential explanatory variables at all sites. White ash populations on upper slopes Health Magnesium consistently had significantly greater dieback, poorer crown condition, and greater mortality than popu- Calcium lations in paired plots on lower slopes. Despite nearly two decades since the last major elm spanworm Defoliation defoliation, this stressor further amplified the differences in health and mortality seen between slope positions.