Research Article Transcutaneous Neuromodulation at Posterior Tibial Nerve and ST36 for Chronic Constipation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China

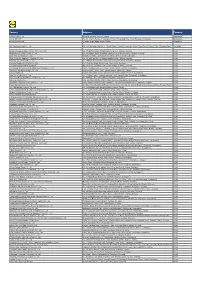

Article DOI: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2510.181699 Risk Factors for Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Zhejiang Province, China Appendix Appendix Table. Surveillance for carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in hospitals, Zhejiang Province, China, 2015– 2017* Years Hospitals by city Level† Strain identification method‡ excluded§ Hangzhou First 17 People's Liberation Army Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Red Cross Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou First People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Hangzhou Children's Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Hospital of Chinese Traditional Hospital 3A Phoenix 100, VITEK 2 Compact Hangzhou Cancer Hospital 3A VITEK 2 Compact Xixi Hospital of Hangzhou 3A VITEK 2 Compact Sir Run Run Shaw Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Children's Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Women's Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University 3A VITEK 2 Compact The First Affiliated Hospital of Medical School of Zhejiang University 3A MALDI-TOF MS The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of 3A MALDI-TOF MS Medicine Hangzhou Second People’s Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang People's Armed Police Corps Hospital, Hangzhou 3A Phoenix 100 Xinhua Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Provincial People's Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Provincial Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine 3A MALDI-TOF MS Tongde Hospital of Zhejiang Province 3A VITEK 2 Compact Zhejiang Hospital 3A MALDI-TOF MS Zhejiang Cancer -

Country Factory Address

Country Factory Address BANGLADESH NOMAN TERRY TOWEL MILLS LTD VAWAL MIRZAPUR, GAZIPUR, BANGLADESH CHINA PUJIANG KINGSHOW CARPET CO NO.75-1 ZHEN PU ROAD, PU JIANG, ZHE JIANG, LTD CHINA CHINA ZHAOYUAN CASTTE GARMENT CO PANJIAJI VILLAGE, LINGLONG TOWN, ZHAOYUAN LTD CITY, SHANDONG PROVINCE, ZHAOYUAN, SHANDONG, CHINA CHINA RUGAO HONGTAI TEXTILE CO LTD XINJIAN VILLAGE, JIANGAN TOWN, RUGAO, JIANGSU, CHINA CHINA NANTONG YAOXING NO.999, TONGFUBEI RD., CHONGCHUAN, NANTONG, JIANGSU, CHINA CHINA CHAOZHOU CHAOAN ZHENGYUN QIAO HU VILLAGE, CHAOAN, CHAOZHOU CITY, CERAMICS INDUSTRIAL CO LTD GUANGDONG, CHINA CHINA YANTAI PACIFIC HOME FASHION NO. 188, PUWAN STREET, FUSHAN DISTRICT YANTAI, FUSHAN MILL SHANDONG, CHINA CHINA SUNVIM GROUP CO LTD MILL 2 NO.1 FURI STR., GAOMI, SHANDONG, CHINA CHINA BAIJIA (FUJIAN) UNDERWEAR CO BAIJIA INDUSTRIAL PARK, HUAHAI VILLAGE, SHENHU LTD - HUAHAI VILLAGE PARK OF JINJIANG ECONOM, JINJIANG, FUJIAN, CHINA CHINA JIAXING SHENGYUAN KNITTING 199 CHAOHUI ROAD, NANHU ECONOMIC AREA, CO., LTD. JIAXING, ZHEJIANG, CHINA CHINA CREATION TEXTILES CO LTD NO. 12 SHITIAN ROAD, YANGCHENGHU TOWN, XIANGCHENG DISTRICT, SUZHOU, JIANGSU, CHINA CHINA JIANDE XINDA METAL CRAFT CO HOU TANG INDUSTRIAL ZONE,GENGLOU STREET, LTD JIANDE, HANGZHOU, ZHEJIANG, CHINA CHINA TONG XIANG ZHONG XIANG 223 FENGXIANG ROAD, TONGXIANG, ZHEJIANG, TEXTILES CO LTD CHINA CHINA FUJIAN JINJIANG HUAMEI DONGSHAN, SHENHU TOWN, JINJIANG, FUJIAN, KNITTING AND CLOTHING CO LTD CHINA CHINA ZHEJIANG WEINA KNITTING YIBEI INDUSTRIAL ZONE, SUXI TOWN, YIWU, INDUSTRIES CO LTD ZHEJIANG, -

Association Between Dietary Patterns and Chronic Kidney Disease in a Middle-Aged Chinese Population

Public Health Nutrition: 23(6), 1058–1066 doi:10.1017/S1368980019002805 Association between dietary patterns and chronic kidney disease in a middle-aged Chinese population Shan-Shan Xu1, Jun Hua2, Yi-Qian Huang3 and Long Shu4,* 1School of Medicine, Huainan Union University, Huainan, Anhui, People’s Republic of China: 2Department of Neurology, General Hospital of Huainan Eastern Hospital, Huainan, Anhui, People’s Republic of China: 3Department of Digestion, Zhejiang Hospital, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, People’s Republic of China: 4Department of Nutrition, Zhejiang Hospital, Xihu District, Hangzhou 310013, Zhejiang, People’s Republic of China Submitted 29 January 2019: Final revision received 14 June 2019: Accepted 19 June 2019: First published online 2 October 2019 Abstract Objective: To explore the relationship between dietary patterns and risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in Chinese adults aged 45–59 years. Design: Dietary data were collected using a semi-quantitative FFQ. Factor analysis was used to identify the major dietary patterns. Logistic regression models were applied to clarify the association between dietary patterns and the risk of CKD. Setting: The present study population was a part of the population-based Nutrition and Health Study performed in the city of Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, eastern China. Participants: A total of 2437 eligible participants (45–59 years) were enrolled in the present cross-sectional study from June 2015 to December 2016. Results: Three major dietary patterns were identified: ‘traditional southern Chinese’, ‘Western’ and ‘grains–vegetables’ patterns, collectively accounting for 25·6 % of variance in the diet. After adjustment for potential confounders, partici- pants in the highest quartile of the Western pattern had greater odds for CKD (OR = 1·83, 95 % CI 1·21, 2·81; P < 0·05) than those in the lowest quartile. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: PAD2392 INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED LOAN IN THE AMOUNT OF US$150 MILLION Public Disclosure Authorized TO THE PEOPLE'S REPUBLIC OF CHINA FOR A ZHEJIANG QIANDAO LAKE AND XIN'AN RIVER BASIN WATER RESOURCES AND ECOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT PROTECTION PROJECT May 15, 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized Environment and Natural Resources Global Practice East Asia And Pacific Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Exchange Rate Effective December 31, 2017 Currency Unit = Chinese Yuan(CNY) CNY1.00 = US$0.15 US$1.00 = CNY 6.70 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asia Development Bank CA Conservation Agriculture CFB Chun’an Finance Bureau CO2 Carbon Dioxide CPMO County Project Management Office CQS Selection Based on the Consultants’ Qualifications CSA Climate Smart Agriculture DA Designated Account EA Environmental Assessment EIA Environmental Impact Assessment ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FBS Selection under a Fixed Budget FM Financial Management FMM Financial Management Manual GHG Greenhouse Gases GoC Government of China GoZ Government of Zhejiang GRS Grievance Redress Service IC Individual Consultant Selection Procedure ICB International -

The Best of Hangz 2019

hou AUGUST 呈涡 The Best of Hangz 2019 TOP ALTERNATIVE BEAUTY SPOTS THE BEST CONVENIENCE STORE ICE-CREAMS TRAVEL DESTINATIONS FOR AUGUST TAKE ME Double Issue WITH YOU Inside Do you want a behind the scenes look at a print publication? Want to strengthen your social media marketing skills? Trying to improve your abilities as a writer? Come and intern at REDSTAR, where you can learn all these skills and more! Also by REDSTAR Works CONTENTS 茩嫚 08/19 REDSTAR Qingdao The Best of Qingdao o AUGUST 呈涡 oice of Qingda 2019 City The V SURFS UP! AN INSIGHT INTO THE WORLD OF SURFING COOL & FRESH, Top (Alternative) WHICH ICE LOLLY IS THE BEST? 12 TOP BEACHES BEACH UP FOR Beauty Spots SUMMER The West Lake is undoubtedly beautiful, but where else is there? Linus takes us through the best of the rest. TAKE ME WITH YOU Double Issue 郹曐暚魍妭鶯EN!0!䉣噿郹曐暚魍旝誼™摙 桹䅡駡誒!0!91:4.:311! 䉣噿壈攢鲷㣵211誑4.514!0!舽㚶㛇誑䯤 䉣墡縟妭躉棧舽叄3123.1125誑 Inside Life’s a Beach Creative Services 14 redstarworks.com Annie Clover takes us to the beach, right here in Hangzhou. Culture 28 Full Moon What exactly is the Lunar Calendar and why do we use it? Jerry answers all. Follow REDSTAR’s Ofcial WeChat to keep up-to-date with Hangzhou’s daily promotions, upcoming events and other REDSTAR/Hangzhou-related news. Use your WeChat QR scanner to scan this code. 饅燍郹曐呭昷孎惡㠬誑䯖鑫㓦椈墕桭 昦牆誤。釣䀏倀謾骼椈墕0郹曐荁饅㡊 㚵、寚棾羮孎惡怶酽怶壚䯋 Creative Team 詇陝筧䄯 Ian Burns, Teodora Lazarova, Toby Clarke, Alyssa Domingo, Jasper Zhai, David Chen, Zoe Zheng, Viola Madau, Linus Jia, Brine Taz, Alison Godwin, Features Vicent Jiang, Mika Wang, May Hao, Business Angel Dong, Wanny Leung, Penny Liu, Lim Jung Eun, Luke Yu, Athena Guo, Cool Off Jordan Coates and Fancy Fang. -

Factory Address Country

Factory Address Country Durable Plastic Ltd. Mulgaon, Kaligonj, Gazipur, Dhaka Bangladesh Lhotse (BD) Ltd. Plot No. 60&61, Sector -3, Karnaphuli Export Processing Zone, North Potenga, Chittagong Bangladesh Bengal Plastics Ltd. Yearpur, Zirabo Bazar, Savar, Dhaka Bangladesh ASF Sporting Goods Co., Ltd. Km 38.5, National Road No. 3, Thlork Village, Chonrok Commune, Korng Pisey District, Konrrg Pisey, Kampong Speu Cambodia Ningbo Zhongyuan Alljoy Fishing Tackle Co., Ltd. No. 416 Binhai Road, Hangzhou Bay New Zone, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Ningbo Energy Power Tools Co., Ltd. No. 50 Dongbei Road, Dongqiao Industrial Zone, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Junhe Pumps Holding Co., Ltd. Wanzhong Villiage, Jishigang Town, Haishu District, Ningbo, Zhejiang China Skybest Electric Appliance (Suzhou) Co., Ltd. No. 18 Hua Hong Street, Suzhou Industrial Park, Suzhou, Jiangsu China Zhejiang Safun Industrial Co., Ltd. No. 7 Mingyuannan Road, Economic Development Zone, Yongkang, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Dingxin Arts&Crafts Co., Ltd. No. 21 Linxian Road, Baishuiyang Town, Linhai, Zhejiang China Zhejiang Natural Outdoor Goods Inc. Xiacao Village, Pingqiao Town, Tiantai County, Taizhou, Zhejiang China Guangdong Xinbao Electrical Appliances Holdings Co., Ltd. South Zhenghe Road, Leliu Town, Shunde District, Foshan, Guangdong China Yangzhou Juli Sports Articles Co., Ltd. Fudong Village, Xiaoji Town, Jiangdu District, Yangzhou, Jiangsu China Eyarn Lighting Ltd. Yaying Gang, Shixi Village, Shishan Town, Nanhai District, Foshan, Guangdong China Lipan Gift & Lighting Co., Ltd. No. 2 Guliao Road 3, Science Industrial Zone, Tangxia Town, Dongguan, Guangdong China Zhan Jiang Kang Nian Rubber Product Co., Ltd. No. 85 Middle Shen Chuan Road, Zhanjiang, Guangdong China Ansen Electronics Co. Ning Tau Administrative District, Qiao Tau Zhen, Dongguan, Guangdong China Changshu Tongrun Auto Accessory Co., Ltd. -

China's Green Bond Issuance and Investment Opportunity Report

China’s Green Bond Issuance and Investment Opportunity Report Report prepared by Climate Bonds Initiative and SynTao Green Finance Supported by UK PACT China’s Green Bond Issuance and Investment Opportunity Report Climate Bonds Initiative 1 Table of contents 1. Introduction and report highlights 3 Climate Bonds Initiative 2. China’s green investment potential 4 The Climate Bonds Initiative (Climate Bonds) is an international 3. China’s policy on green finance and 8 investor-focused not-for-profit organisation working to mobilise green bonds the USD100tn bond market for climate change solutions. 4. Opportunities for green bond issuance 12 It promotes investment in projects and assets needed for in China’s green finance pilot zones a rapid transition to a low carbon and climate resilient economy. The mission focus is to help drive down the cost of capital for large-scale climate and infrastructure projects and to Zhejiang Province support governments seeking increased capital markets investment to meet climate and greenhouse gas (GHG) Guangdong Province emission reduction goals. Xinjiang Province Climate Bonds carries out market analysis, policy research, market development; advises governments and regulators; Guizhou Province and administers the Climate Bonds Standards and Certification Scheme. Jiangxi Province Gansu Province 5. Moving forward: challenges and 18 opportunities to financing green projects in China 6. Appendices 20 Appendix 1: Green debt instruments Appendix 2: Sample Green Pipeline Appendix 3: Climate Bonds Taxonomy SynTao Green Finance SynTao Green Finance is a leading ESG service provider in China, that is dedicated to professional services in green finance and sustainable investment. It is committed to providing professional services ranging from ESG data and rating, green bond assurance, to the consulting and researching services in the sustainable investment and green finance areas. -

List of Main Production Facilities of ALDI Nord's Suppliers for Apparel

List of Main Production Facilities of ALDI Nord‘s Suppliers for Apparel, Home Textiles and Shoes Version: April 2021 Produktionsstättenliste | März 2018 | Seite 0/17 Name Address Number of Employees Commodity Group Bangladesh AB Apparels Ltd. 225, Singair Road, Tetuljhora, Hemayetpur 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Ador Composite Ltd. 1, C & B Bazar, Gilarchala, Sreepur 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles AKH Eco Apparels Ltd. 495, Balitha, Shahbelishwar, Dhamrai 5001 - 10000 Garment textiles Angshuk Ltd. 133-134, Hamayetpur, Savar 501 - 1000 Garment textiles Apparels Village Ltd. Khagan, Birulia, Savar 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Aspire Garments Ltd. 491, Dhalla, Singair 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles B.H.I.S. Apparels Ltd. 671, Datta Para, Hossain Market, Tongi 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Blue Planet Knitwear Ltd. Mulaid, P.O.: Tengra, Sreepur 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles Chaity Composite Ltd. Chotto Silmondi, Tripurdi, Sonargaon 5001 - 10000 Garment textiles Chantik Garments Ltd. Kumkumari, Gouripur, Ashulia, Savar 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Chorka Textile Ltd. Kajirchor, Danga Bazar, Polash 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Citadel Apparels Ltd. Joy Bangla Road, Kunia, K.B. Bazar, Gazipur Sadar 501 - 1000 Garment textiles Cotton Dyeing & Finishing Mills Ltd. Vill: Amtoli, Union: 10 No. Habirbari, P.O-Seedstore Bazar, P.S.-Valuka 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles Crossline Factory (Pvt) Ltd. 25, Vadam, Uttarpara, Nishatnagar, Tongi 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles Plot No. 45, 48, 49, 51 & 52; Holding No.: 3/C, Vadam, P.O.: Crossline Knit Fabrics Ltd. 1001 - 2000 Garment textiles Nishatnagar, Tongi, Gazipur-1711, Gazipur Crown Exclusive Wears Ltd. Mawna, Sreepur 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Crown Fashion & Sweater Industries Ltd. Plot No. 781-782, Vogra, Joydebpur, Gazipur-1704 2001 - 5000 Garment textiles Denim Fashions Ltd. -

中國中鐵股份有限公司 CHINA RAILWAY GROUP LIMITED (A Joint Stock Limited Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 390)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. 中國中鐵股份有限公司 CHINA RAILWAY GROUP LIMITED (A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 390) This overseas regulatory announcement is made pursuant to Rule 13.10B of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited. Please refer to the attached “Announcement of China Railway Group Limited on Winning of Bids for Material Projects” published by China Railway Group Limited on the Shanghai Stock Exchange website on 25 May 2020 for your information. By Order of the Board China Railway Group Limited Zhang Zongyan Chairman 25 May 2020 As at the date of this announcement, the executive directors of the Company are ZHANG Zongyan (Chairman), CHEN Yun, WANG Shiqi and ZHANG Xian; the independent non-executive directors are GUO Peizhang, WEN Baoman, ZHENG Qingzhi and CHUNG Shui Ming Timpson; and the non-executive director is MA Zonglin. A Shares Stock Code: 601390 A Shares Stock Name: China Railway Announcement No.: H Shares Stock Code: 00390 H Shares Stock Name: China Railway Lin 2020-040 Announcement of China Railway Group Limited on Winning of Bids for Material Projects The board of directors of China Railway Group Limited (the “Company”) and all the directors hereby undertake that this announcement does not have any false or misleading statements or any material omissions, and assume the joint and several liabilities for the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the contents. -

Multiple Lineages of Dengue Virus Serotype 2 Cosmopolitan Genotype

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Multiple Lineages of Dengue Virus Serotype 2 Cosmopolitan Genotype Caused a Local Dengue Outbreak Received: 13 August 2018 Accepted: 26 April 2019 in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, Published: xx xx xxxx China, in 2017 Hua Yu1, Qingxin Kong2, Jing Wang2, Xiaofeng Qiu1, Yuanyuan Wen2, Xinfen Yu1, Muwen Liu2, Haoqiu Wang1, Jingcao Pan1 & Zhou Sun2 During July to November 2017, a large dengue outbreak involving 1,138 indigenous cases occurred in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China. All patients were clinically diagnosed as mild dengue. Epidemiology investigation and phylogenetic analysis of circulating viruses revealed that at least three lineages of dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV-2) Cosmopolitan genotype initiated the outbreak during a short time. The analysis of the time to most recent common ancestor estimated that the putative ancestor of these DENV-2 lineages might rise no later than March, 2017, suggesting independent introductions of these lineages into Hangzhou. We presumed that group travelers visiting dengue- endemic areas gave rise to multiple introductions of these lineages during so short a time. Co-circulating of multiple DENV-2 lineages, emerging of disease in urban areas, hot and humid weather in Hangzhou adequate for mosquito breeding, and limited dengue diagnosis abilities of local hospitals, were the reasons causing the large local outbreak in Hangzhou. Dengue is a mosquito-borne infectious disease caused by dengue viruses (DENVs) which consists of four anti- genically distinct but closely related serotypes (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4). Dengue prevails in tropical and sub-tropical regions worldwide. It has been estimated recently that a total of 58.40 million sympto- matic dengue viral infections, including 13.57 thousand fatal cases, occurred globally in 2013 (ref.1). -

Annex 1 Resettlement Policy Framework

RP968 World Bank Financed Project V1 Public Disclosure Authorized Qiantang River Basin Small Towns Environment Project Resettlement Action Plan Public Disclosure Authorized (Consolidated Report) Public Disclosure Authorized June 5, 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized Qiantang Basin Environmental Comprehensive Treatment Project Resettlement Plan — Financed by World Bank Foreword 1. The objective of Resettlement Action Plan As been shown by the past experience of World Bank(WB), the involuntary resettlements in develop programs are yet get relieved, but also lead to severe economical, social and environmental crisis, such as the desegregation of production system, the miss of production capital or income resource, threaten of poverty; the movement to the environment where the productive skills may not available and the competitions of resources aggravated; the power of communities and social net-work may be weaken; family bone may be drifted apart; culture identity, custom authority and mutual aid face the risk of impairing and disappearing. This Resettlement Action Plan (RAPRAP) is formulated on the basis of the laws, regulations and policies of the People’s Republic of China, and Local Government as well as the Guidelines of the World Bank (Operational Directive for Involuntary Resettlement OP 4.12). The purpose of this document is to set out an Action plan for the Resettlement and Rehabilitation of the Affected persons (APs) to ensure that they will benefit from the project and their standards of living will be improved or at least be restored after the project impact. 2. The aim of Resettlement Action Plan To setting out an Action plan for the Resettlement and Rehabilitation of the APs to ensure that they will gain the compensation and their standards of living will be improved or at least be restored after the project impact; to have the affected productiveness wealth (including business stores, corporations and institutes), public wealth, infrastructure and culture heritage improved or at least restored to the present standards. -

Material Safety Data Sheet

7 Material Safety Data Sheet COLORED CHALKS MSDS NO.:AJT131101096E 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY IDENTIFICATION Product Name: Colored chalks Product Use: Toys, Writing Supplier Information Company Name: TIANJIN ZHONGRUI STATIONERY PRODUCTS CO., LTD Address: 6 ZHENXING ROAD, NORTH INDUSTRIAL ESTATE, JINGHAI, TIANJIN, CHINA, 301600 Tel: 0086-22-28945515 Fax: 0086-22-28943852 Email: [email protected] Emergency Telephone: 0086-22-28942604 2. HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION EMERGENCY OVERVIEW: This product is not expected to produce any unusual hazards during normal use. Exposure to high dust levels may irritate the skin, eyes, nose, throat, or upper respiratory tract. POTENTIAL HEALTH EFFECTS ACUTE: Eyes: Airborne dust or direct contact can cause mechanical irritation of eyes. If burning, redness, itching, pain or other symptoms persist or develop, consult physician. Skin: Direct, prolonged or repeated contact with the skin may cause irritation. Inhalation: Dust exposures generated during the handling of the product may irritate eyes, skin, nose, throat, and upper respiratory tract. Persons subjected to large amounts of this dust will be forced to leave area because of nuisance conditions such as coughing, sneezing and nasal irritation. Labored breathing may occur after excessive inhalation. If respiratory symptoms persist, consult physician. Ingestion: If ingested may cause temporary irritation to the gastrointestinal tract, especially the stomach. No known effects. CHRONIC: Eyes: None known. Skin: None known. Ingestion: No known effects. Inhalation: Testing of dust from gypsum powders has not detected respirable crystalline silica. Exposures to respirable crystalline silica are not expected during the normal use of this product; however, actual levels must be determined by workplace hygiene testing.