Having to Science the Hell out Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001

Cumulated Bibliography of Biographies of Ocean Scientists Deborah Day, Scripps Institution of Oceanography Archives Revised December 3, 2001. Preface This bibliography attempts to list all substantial autobiographies, biographies, festschrifts and obituaries of prominent oceanographers, marine biologists, fisheries scientists, and other scientists who worked in the marine environment published in journals and books after 1922, the publication date of Herdman’s Founders of Oceanography. The bibliography does not include newspaper obituaries, government documents, or citations to brief entries in general biographical sources. Items are listed alphabetically by author, and then chronologically by date of publication under a legend that includes the full name of the individual, his/her date of birth in European style(day, month in roman numeral, year), followed by his/her place of birth, then his date of death and place of death. Entries are in author-editor style following the Chicago Manual of Style (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 14th ed., 1993). Citations are annotated to list the language if it is not obvious from the text. Annotations will also indicate if the citation includes a list of the scientist’s papers, if there is a relationship between the author of the citation and the scientist, or if the citation is written for a particular audience. This bibliography of biographies of scientists of the sea is based on Jacqueline Carpine-Lancre’s bibliography of biographies first published annually beginning with issue 4 of the History of Oceanography Newsletter (September 1992). It was supplemented by a bibliography maintained by Eric L. Mills and citations in the biographical files of the Archives of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, UCSD. -

Document View

Document View http://proquest.umi.com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/pqdlink?index=1&s... Databases selected: Multiple databases... Salmon farms destroying wild salmon populations in Canada, Europe: study ALISON AULD . Canadian Press NewsWire . Toronto: Feb 11, 2008. Abstract (Summary) The authors, including the late Halifax biologist Ransom Myers, claim the study is the first of its kind to take an international view of stock sizes in countries that have significant salmon aquaculture industries. The paper didn't look to the causes of the declines, which have been discussed in a series of studies over the last decade that have linked disease, interbreeding of escaped salmon and lice from farmed fish with reductions. Full Text (618 words) Copyright Canadian Press Feb 11, 2008 HALIFAX _ Salmon farming operations have reduced wild salmon populations by up to 70 per cent in several areas around the world and are threatening the future of the endangered stocks, according a new scientific study. The research by two Canadian marine biologists showed dramatic declines in the abundance of wild salmon populations whose migration takes them past salmon farms in Canada, Ireland and Scotland. ``Our estimates are that they reduced the survival of wild populations by more than half,'' Jennifer Ford, lead author of the study published Monday in the Public Library of Science journal, said in Halifax. ``Less than half of the juvenile salmon from those populations that would have survived to come back and reproduce actually come back because they're killed by some mechanism that has to do with salmon farming.'' The authors, including the late Halifax biologist Ransom Myers, claim the study is the first of its kind to take an international view of stock sizes in countries that have significant salmon aquaculture industries. -

Adventures In

BULLETIN Fall 2009 adventurEs in sCIENCE Ingree’sPort IncludesYear end P re board of trustees 2008–09 Jane Blake Riley ’77, p ’05 President contents James D. Smeallie p ’05, ’09 V ice President Keith C. Shaughnessy p ’04, ’08, ’10 T reasurer Philip G. Lake ’85 4 Pingree Secretary athletes Thanks Anthony G.L. Blackman p ’10 receive Interim Head of School All-American Nina Sacharuk Anderson ’77, p ’09 ’11 honors for stepping up to the plate. Kirk C. Bishop p ’06, ’06, ’08 Tamie Thompson Burke ’76, p ’09 Patricia Castraberti p ’08 7 Malcolm Coates p ’01 Honoring Therese Melden p ’09, ’11 Reflections: Science Teacher Even in our staggering economy, Theodore E. Ober p ’12 from Head of School Eva Sacharuk 16 Oliver Parker p ’06, ’08, ’12 Dr. Timothy M. Johnson Jagruti R. Patel ’84 you helped the 2008–2009 Pingree William L. Pingree p ’04, ’08 3 Mary Puma p ’05, ’07, ’10 annual Fund hit a home run. Leslie Reichert p ’02, ’07 Patrick T. Ryan p ’12 William K. Ryan ’96 Binkley C. Shorts p ’95, ’00 • $632,000 raised Joyce W. Swagerty • 100% Faculty and staff participation Richard D. Tadler p ’09 William J. Whelan, Jr. p ’07, ’11 • 100% Board of trustees participation Sandra Williamson p ’08, ’09, ’10 Brucie B. Wright Guess Who! • 100% class of 2009 participation Pictures from Amy McGowan p ’07, ’10 the archives 26 • 100% alumni leadership Board participation Parents Association President William K. Ryan ’96 • 15% more donations than 2007–2008 A Lumni L eadership Board President Cover Story: • 251 new Pingree donors board of overseers Adventures in Science Alice Blodgett p ’78, ’81, ’82 Susan B. -

Pauly D (2009) Beyond Duplicity and Ignorance in Global Fisheries. Scient

FEATURE ARTICLE SCIENTIA MARINA 73(2) June 2009, 215-224, Barcelona (Spain) ISSN: 0214-8358 doi: 10.3989/scimar.2009.73n2215 Beyond duplicity and ignorance in global fisheries* DANIEL PAULY Sea Around Us Project, Fisheries Centre Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, V6T 1Z4, Canada. SUMMARY: The three decades following World War II were a period of rapidly increasing fishing effort and landings, but also of spectacular collapses, particularly in small pelagic fish stocks. This is also the period in which a toxic triad of catch underreporting, ignoring scientific advice and blaming the environment emerged as standard response to ongoing fisheries collapses, which became increasingly more frequent, finally engulfing major North Atlantic fisheries. The response to the depletion of traditional fishing grounds was an expansion of North Atlantic (and generally of northern hemisphere) fisher- ies in three dimensions: southward, into deeper waters and into new taxa, i.e. catching and marketing species of fish and invertebrates previously spurned, and usually lower in the food web. This expansion provided many opportunities for mis- chief, as illustrated by the European Union’s negotiated ‘agreements’ for access to the fish resources of Northwest Africa, China’s agreement-fee exploitation of the same, and Japan blaming the resulting resource declines on the whales. Also, this expansion provided new opportunities for mislabelling seafood unfamiliar to North Americans and Europeans, and mislead- ing consumers, thus reducing the impact of seafood guides and similar effort toward sustainability. With fisheries catches declining, aquaculture—despite all public relation efforts—not being able to pick up the slack, and rapidly increasing fuel prices, structural changes are to be expected in both the fishing industry and the scientific disciplines that study it and in- fluence its governance. -

Fisheries Centre Report 1993-2000

19931993 -- 20002000 ReportReport TheThe FFisheriesisheries CentrCentree UnivUniversityersity ofof BritishBritish ColumbiaColumbia Forewords want to congratulate all the members of the Fisheries Centre whose Iachievements are recorded in this excellent report. Over a very short time period, the Centre has contributed many exciting new initiatives in the areas of sustainable development and the planned growth of our fisheries. British Columbia is a vast treas- ure-house of natural resources, but we must exercise responsible stewardship over the complex ecosystems that surround us if we hope to preserve that treasure for future generations. The Fisheries Centre brings together government agencies, First Nations, and the University in a vital collaboration, offering an excellent model of how to ad- dress an issue of both regional and global importance through multidisciplinary research and teaching. Many problems lie ahead, but this report gives us reason to be optimistic about our ability to find solutions. DR MARTHA PIPER PRESIDENT, UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA am delighted that, in its first eight years, the Fisheries Centre is successfully Ifulfilling its mandate as one of 26 interdisciplinary research units within the Faculty of Graduate Studies. The output reviewed in this report not only underlines the Centres influential global role in its field, but also reflects the remarkable drive and enthusiasm of its members. An internal report in 1996 identified poor accommodation as one of the main weaknesses and so we are pleased to see reported here the success in attracting Canada Foundation for Innovation funding that will provide a new home for Fisheries Centre members. The Faculty of Graduate Studies is proud to provide con- tinuing support for the Fisheries Centre in its activities. -

The Role of Climate Change

The Buckland Foundation The Role of climate change Dr John K. Pinnegar Second Buckland Fisheries Colloquium, Tuesday 2nd June 2015, Fishmongers’ Hall, London Bridge The Buckland Foundation The North Sea – a ‘hot spot’ of climate change….. One of 20 sites identified by Hobday & Pecl (2013) as having warmed the fastest The Buckland Foundation Observed ‘northward’ distribution shifts Temperature response 72% of the fish species have responded to warming by changing distribution and abundance (Simpson et al. 2011) 2011). Centres of distribution have generally shifted by distances ranging from 48 to 403 km (Perry et Winners & Losers al. 2005). The North Sea demersal fish assemblage deepened by ~3.6 m per decade between 1980 and 2004 (Dulvy et al. 2008). Catches (1913–2007) of cod, haddock, plaice and sole have all shifted distribution albeit not in a consistent way (Engelhard et al. 2011). In the UK we have witnessed both “winners” and “losers” The Buckland Foundation Lots of media coverage: th nd BBC Wildlife, August 2012 The Guardian, 9 May 2012 Scientific American, 2 July 2012 The Buckland Foundation Year class strength and implications for fisheries Fishermen and scientists have known for over 100 years that the status of fish stocks can be greatly influenced by prevailing weather conditions (Hjort Planque & Fox 1914). (1998), Irish Sea Johan Hjort (1869- 1948) Recruitment variability, is a key measure of the productivity of a fish stock, In the case of cod, there is a well established relationship between recruitment and sea temperature (O’Brien et al. 2000; Clarke et al. 2003; Beaugrand et al. -

Towards a Science of Recruitment in Fish Populations

OTTO KINNE Editor David H. Cushing TOWARDS A SCIENCE OF RECRUITMENT IN FISH POPULATIONS Introduction (Otto Kinne) David H. Cushing: A Laudatio (John D. Costlow) O L O G C Y Publisher: Ecology Institute E I Nordbünte 23, D-21385 Oldendorf/Luhe N E S T Germany T I T U David H. Cushing 198 Yarmouth Rd. Lowestoft Suffolk NR32 4AB United Kingdom ISSN 0932-2205 Copyright © 1996, by Ecology Institute, D-21385 Oldendorf/Luhe, Germany All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, or transmitted, or translated without written permission of the publisher Printed in Germany Typesetting by Ecology Institute, Oldendorf Printing and bookbinding by Westholsteinische Verlagsdruckerei Boyens & Co., Heide Printed on acid-free paper Contents Introduction (Otto Kinne) . VII David H. Cushing: A Laudatio (John Costlow) . XVII Preface . XX I HISTORY OF THE FISHERIES . 1 The Long History of the Fisheries . 1 Variability and Management . 8 II CLIMATE AND FISHERIES . 23 Faunal Movements and the Recent Period of Warming . 23 Evidence of Climate Effects . 25 Responses of Five Pelagic Stocks to Climate Changes . 28 The Climate of the North Atlantic . 37 Russell Cycle . 41 West Greenland Cod Stock . 45 Great Salinity Anomaly of the Seventies . 50 Zooplankton in the North Sea . 53 Gadoid Outburst . 55 A Broader View . 58 III A SIMPLE VIEW OF RECRUITMENT . 65 When Is the Magnitude of Recruitment Determined? . 65 Lack of Food . 70 Field Studies . 78 Predation . 83 Variability of Recruitment . 86 Match/Mismatch Hypothesis . 90 A Model of Match . 95 Conclusion . 103 IV NATURE OF THE STOCK RECRUITMENT RELATIONSHIP . -

Review Article Revival and Recent Advancements in the Spatial Fishery

ICES Journal of Marine Science (2021), doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsab021 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/icesjms/advance-article/doi/10.1093/icesjms/fsab021/6288531 by NOAA Central Library user on 16 June 2021 Review Article Contribution to the Themed Section: ‘A tribute to the life and accomplishments of Sidney J. Holt’ Revival and recent advancements in the spatial fishery models originally conceived by Sidney Holt and Ray Beverton Daniel R. Goethel 1,* and Steven X. Cadrin2 1Marine Ecology and Stock Assessment Program, Auke Bay Laboratories, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 17109 Pt. Lena Loop Road, Juneau, AK 99801, USA 2Department of Fisheries Oceanography, School for Marine Science & Technology, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth, 836 South Rodney French Boulevard, New Bedford, MA 02744, USA *Corresponding author: tel: þ1 (907) 789-6000; e-mail: [email protected] Goethel, D. R. and Cadrin, S. X. Revival and recent advancements in the spatial fishery models originally conceived by Sidney Holt and Ray Beverton. – ICES Journal of Marine Science, doi:10.1093/icesjms/fsab021. Received 15 November 2020; revised 22 January 2021; accepted 26 January 2021. Sidney Holt and Ray Beverton are primarily recognized for developing the basis of demographic stock assessment modelling, but their endur- ing legacy continues to influence and guide advancements in many fields of fisheries science. Although largely forgotten, their contributions to spatial modelling laid the foundation for a variety of applications in aquatic and terrestrial populations. Spatial modelling approaches are rapidly evolving beyond even the visionary scope of Beverton and Holt due to advancements in understanding of spatial population structure, collection of spatially explicit data, and statistical parameter estimation. -

Remote Sensing for Fisheries

Remote Sensing for Fisheries Shubha Sathyendranath and Trevor Platt Plymouth Marine Laboratory UK Fisheries Applications of EO include: • Harvest Fisheries - economies of fuel and time • Fisheries Management - intelligence on ecosystem fluctuations and effect on future states of exploited stocks • Aquaculture Industry - carrying capacity, harmful algal blooms For further details, see IOCCG Report No. 8 • Protection of Species at Risk - exclusion zones and reduction of by-catch •Marine Protected Areas & Vulnerable Marine Ecosystems - delineation of these • Ecosystem Health and Ecosystem Services - monitoring health, evaluating services • High Seas Governance - international governance strategy, ecosystem delineation, straddling stocks What some countries are doing INDIA Routinely delivers remotely-sensed data (chlorophyll and temperature) to fishing communities all around the coast, in local languages. JAPAN Routinely delivers temperature and chlorophyll data to fishing fleets (near-shore and offshore), each vessel equipped with standard computer and standard software. Fish Harvesting – commercial applications TOREDAS System – Japan Information system using RS/GIS for the offshore fisheries activities around Japan Sei-Ichi Saitoh1, 2, Fumihiro Takahashi2 and colleagues 1Hokkaido University 2SpaceFish LLP Use Chl-a, currents and SST fronts to determine squid fishing grounds (red) Target species: Japanese common squid, Pacific saury, albacore tuna, skipjack tuna Saithoh et al. (2010) Potential Fishing Zone Identification by Remote Sensing: -

September 1997 Sept 1997 Volume 18, Number 2 Newsletter of the AFS

September 1997 Newsletter of the AFS Early Life History Section Volume 18, Number 2 Sept 1997 Inside this Issue PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE m President’s message he 21st Annual Larval Fish Con- choice among several excellent m News from the re- ference was held in Seattle, papers, with votes ending in a tie gions Washington from 26 June - 2 between two deserving students. m Northeast July, 1997. More than 200 par- The 1997 Richardson Award m Northcentral ticipants were treated to a di- winners are: Jennifer Caselle, verse scientific program, includ- from the University of Califor- m Western ing symposia on "Juvenile Fish nia, Santa Barbara for a paper m Southern Studies: Contributions to Early titled ‘Density-dependent early m International Life History and Recruitment post-settlement mortality in m ELH’ers in the news Processes" and "Ontogeny of coral reef fish and its effect on m Meeting reviews North Pacific Scorpaeniform local populations’ and Ule Rein- m Upcoming meetings Fishes" as well as workshops on hardt from the University of "Larval Fish Identification," British Columbia for a paper "Preservation and Curation of titled ‘Size-dependent foraging Early Life History Stages of behaviour and use of cover in Fishes, Amphibians, and Rep- juvenile coho salmon under pre- Abstract Deadlines: tiles," and "Image Analysis". dation risk’. Honorable Men- The ELHS wishes to thank the tions go to Jason Rogers, from AFS, - Jan 23 local organizing committee, es- the University of North Car- to be held Aug 23-27, pecially Art Kendall and Ann olina, Wilmington for a paper 1998 at the Hartford Civic Matarese, for a job well done!!! titled ‘Age and growth of larval Center, Hartford, CT An award for the best and pelagic juvenile Monacan- student paper presented at the thus hispidus’ and Jay Rooker, Larval Fish Conference is given from the University of Texas, by the ELHS each year in honor Austin for a paper titled ‘Small- ASI H of the late Sally Richardson. -

On the History of Marine Fisheries Woods Hole Workshop, August 26, 1998

On the History of Marine Fisheries Woods Hole Workshop, August 26, 1998 John H. Steele and Andrew R. Solow Meeting Co-Chairs, Marine Policy Center, WHOI Mary Schumacher, Rapporteur Marine Policy Center, WHOI Tim Baumgartner, Scripps Institute of Oceanography David Cushing, Marine Biological Laboratory, Lowestoft Larry Madin, Chair, Biology Dept. WHOI Ransom Myers, Chair, Biology Dept. Dalhousie University Daniel Pauly, Fisheries Center, University of British Columbia Ken Sherman, NMFS-Narragansett Bay Mike Sissenwine, Director, NMFS-Woods Hole Tim Smith, NMFS-Woods Hole Peter Wiebe, Biology Dept., WHOI SUMMARY The Marine Policy Center of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hosted a workshop entitled "On the History of Marine Fisheries" on August 26, 1998. Sponsored by the Sloan Foundation, the workshop was part of a larger Sloan effort to assess the feasibility of a large- scale program to improve the state of knowledge about the current and potential global diversity, abundance, and distribution of marine life. The theme of the Woods Hole workshop was selected in light of the recommendations of an earlier Sloan-sponsored meeting held in Monterey in April 1998. Participants in the Monterey meeting had proposed an iterative process of modeling and observation, with a pilot observational phase that would concentrate on filling in large unknowns in existing ecosystem models, especially information about the diversity, abundance, and distribution of biomass at the upper trophic levels. Participants in the Woods Hole workshop were asked to address two main questions: (1) What do modeling and observational studies tell us about the state of marine fisheries prior to, and in the early stages of, exploitation? (2) What further studies should be undertaken to improve the state of knowledge in this area? Participants’ responses to the first question converged on a few key themes. -

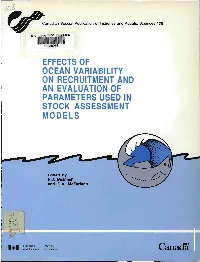

Effects of Ocean Variability on Recruitment and an Evaluation of Parameters Used in Stock Assessment Models

Canadian Special Publication of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 108 DFO - Libra y ! MPO B Lai othèque 11 EFFECTS OF OCEAN VARIABILITY ON RECRUITMENT AND AN EVALUATION OF PARAMETERS USED IN STOCK ASSESSMENT MODELS Edited by R.J. Beamish and G.A. McFarlane qL c3H tkid Fisheries Pêches 1+1 and Oceans et Océans Canadhl Canadian Special Publication of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 108 Effects of Ocean Variability on Recruitment and an Evaluation of Parameters Used in Stock Assessment Models : 1.11; RA V% Y (Proceedings of the International Symposium held at 1990 Vancouver, British Columbia, October 26-29, 1987) 1 FEEVB 6_ e iellor-itouE Edited by Pôchot; R. J. Beamish and G. A. McFarlane Department of Fisheries and Oceans Biological Sciences Branch Pacific Biological Station Nanaimo, British Columbia V9R 5K6 Scientific Excellence Resource Protection & Conservation Benefits for Canadians Sponsored by International Recruitment Investigations in the Subarctic (IRIS) and International North Pacific Fisheries Commission (INPFC) DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES AND OCEANS OTTAWA 1989 Published by Publié par Fisheries Pêches EMI and Oceans et Océans Communications Direction générale Directorate des communications © Minister of Supply and Services Canada 1989 Available from authorized bookstore agents, other bookstores or you may send your prepaid order to the Canadian Government Publishing Centre Supply and Services Canada, Ottawa, Ont. K1A 0S9 Make cheques or money orders payable in Canadian funds to the Receiver General for Canada. A deposit copy of this publication is also available for reference in public libraries across Canada. Cat. No. Fs 41-31/108E ISBN 0-660-13360-1 ISSN 0706-6481 DF0/4220 Communications Directorate Director General: Nicole Deschênes Director: John Camp Editorial and Publishing Services: Gerald J.