Fiction Is Like Fire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6:15 Pm Parthenon A

South Central Modern Language Association 72nd Annual Conference October 31 - November 3, 2015 Nashville Marriott at Vanderbilt University Nashville, Tennessee SCMLA CONFERENCE PROGRAM A PDF version of this program is available on our website: www.southcentralmla.org South Central Modern Language Association University of Oklahoma 332 Cate Center Drive, Room 481 Norman, OK 73019-6410 Phone: (405) 325-6011 Fax: (405) 325-3720 Email: [email protected] Web: www.southcentralmla.org 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2015 Executive Committee ……………………………………………………………………. 3 Special Thanks ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Conference Hosts …………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Friends of SCMLA …………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Sustaining Departmental Members ……………………………………………………….. 7 SCMLA Life and Honorary Members ………………………………………………………. 8 Schedule of Events ………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Summary of Conference by Session Type …………………………………………….. 10 Conference Program ……………………………………………………………………………. 19 Grants, Awards and Prizes …………………………………………………………………….71 Grant and Prize Winners ……………………………………………………………………… 73 2016 SCMLA Deadlines ……………………………………………………………………….. 74 2 SCMLA 2015 Executive Committee Jeanne Gillespie, President University of Southern Mississippi [email protected] Melissa Bailar, Past President Rice University [email protected] Julie Chappell, Vice President Tarleton State University [email protected] Emily D. Johnson, Executive Director University of Oklahoma [email protected] Richard J. Golsan, Editor (2013-2017) South Central Review Texas -

CHARLES EAST PAPERS Mss

Access to unprocessed collections requires the permission of the Head of Archival Processing, subject to Special Collections’ Policy on Access to Unprocessed Collections (https://www.lib.lsu.edu/special/about/policies/unprocessed) CHARLES EAST PAPERS Mss. 3471 Container List Louisiana and Lower Mississippi Valley Collections Special Collections, Hill Memorial Library Louisiana State University Libraries Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Updated 2019, 2021 CHARLES EAST PAPERS Mss. 3471 circa 1849-2005 LSU LIBRARIES SPECIAL COLLECTIONS CONTENTS OF INVENTORY SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................... 3 BIOGRAPHICAL/HISTORICAL NOTE ...................................................................................... 4 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE ................................................................................................... 7 INDEX TERMS .............................................................................................................................. 8 CONTAINER LIST ........................................................................................................................ 9 Use of manuscript materials. If you wish to examine items in the manuscript group, please place a request via the Special Collections Request System. Consult the Container List for location information. Photocopying. Should you wish to request photocopies, please consult a staff member. Do not remove items to be photocopied. The -

BEYOND the PAGES University of Georgia Libraries

Volume 23 Spring 2016 BEYOND THE PAGES University of Georgia Libraries VISIT THE LIBRARIES' WEBSITES www.libs.uga.edu Special Collections Library UGA Libraries Contact Information www.libs.uga.edu/scl Dr. P. Toby Graham University Librarian and Associate Provost Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library [email protected] www.libs.uga.edu/hargrett (706) 542-0621 Chantel Dunham Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research & Studies Director of Development www.libs.uga.edu/russell [email protected] (706) 542-0628 Walter J. Brown Media Archive & Peabody Awards Collection www.libs.uga.edu/media Leandra Nessel Development Officer [email protected] (706) 542-3879 SUPPORT OUR ORAL HISTORY Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library TEACHING AND RESEARCH MISSION Chuck Barber Kat Stein Interim Codirector Interim Codirector [email protected] [email protected] (706) 542-0669 (706) 542-5484 Ruta Abolins Director, Walter J. Brown Media Archives and Peabody Awards Collection [email protected] (706) 542-4757 Sheryl B. Vogt Director, Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies [email protected] (706) 542-0619 Alexander M. Stephens interviews Sheila McAlister longtime Athens resident Bennie Director, Digital Library of Georgia McKinley. [email protected] (706) 542-5418 The Richard B. Russell Library is a state and national leader for oral history programming. Researchers | (706) 542-7123 It is the only UGA unit producing oral histories and making collections available for research. Events | (706) 542-6331 Aligned with UGA’s new experiential learning requirement and the University’s 2020 Strategic Tours | (706) 542-8079 Plan, the Russell Oral History program allows students to explore modern history using tech- nology to enhance learning and to share their research products. -

Selected Backlist

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? FALL & WINTER 2019 DIGITAL BACKLIST CATALOG UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA PRESS UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA PRESS ART & ARCHITECTURE ART & ARCHITECTURE the afro- the andrew the architecture american low house of francis palmer tradition in Tania June Sammons smith, atlanta’s decorative arts with Virginia Connerat scholar architect John Michael Vlach Logan Robert M. Craig 196 illus. 59 color and b&w 418 color and b&w photos paperback $33.95 photos, 1 diagram hardback $60 9780820312330 hardback $19.95 9780820328980 9780820353982 architecture art of the brothers in clay of middle cherokee The Story of Georgia Folk georgia Prehistory to the Pottery The Oconee Area Present John A. Burrison John Linley Susan C. Power 167 color and b&w photos 314 b&w photos, 55 color and 20 b&w paperback $37.95 4 figures, 9 floor plans, photos, 3 maps 9780820332208 18 maps paperback $29.95 paperback $34.95 9780820327679 9780820346120 courthouses democracy early art of the of georgia restored southeastern Association County A History of the Georgia indians Commissioners of State Capitol Feathered Serpents and Georgia Timothy J. Crimmins Winged Beings Photographs by and Anne H. Farrisee Susan C. Power Greg Newington Featuring Photographs 24 color and 45 b&w Text by George Justice by Diane Kirkland photos, 3 maps 160 color photos, 105 color photos, 129 paperback $38.95 10 maps b&w photos 9780820347462 hardback $34.95 hardback $41.95 9780820346885 9780820329116 ellen shipman flannery from mud to jug and the american o’connor’s The Folk Potters and garden georgia Pottery of Northeast Judith B. Tankard Photographs and text Georgia 190 duotone photos, by Barbara McKenzie John A. -

Book Review: After O'connor: Stories from Contemporary Georgia William W

The Southeastern Librarian Volume 52 | Issue 2 Article 8 Summer 2004 Book Review: After O'Connor: Stories from Contemporary Georgia William W. Starr Georgia Center for the Book, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/seln Recommended Citation Starr, William W. (2004) "Book Review: After O'Connor: Stories from Contemporary Georgia," The Southeastern Librarian: Vol. 52 : Iss. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/seln/vol52/iss2/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Southeastern Librarian by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hugh Ruppersburg, (Editor) Sharyn McCrumb. AFTER O’CONNOR: Stories from Contemporary Ghost Riders. Dutton, 2003. 333p. Georgia. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2003, 375 p. With Ghost Riders, Sharyn McCrumb has written a Civil War novel from the prospective of the North The publication of this collection ought to be an Carolina mountain country, from both present and past occasion to celebrate not only the quality of writing in points of view. Having researched the period, the Georgia these days but the number of writers outcome is thought-provoking and educational. By producing it. The 30 authors represented in this new moving us between the past and the present, she (September 2003) volume certainly reflect a proud interweaves the lives of a number of characters: diversity: old, young, black, white, Asian. They are Rattler, a part Cherokee healer; Nora Bonesteel, a seemingly an eclectic assemblage of varying styles woman with the “sight;” Tom Gentry, bent on and experiences whose diversity is their only bond. -

6:15 Pm Parthenon A

South Central Modern Language Association 72nd Annual Conference October 31 - November 3, 2015 Nashville Marriott at Vanderbilt University Nashville, Tennessee SCMLA CONFERENCE PROGRAM A PDF version of this program is available on our website: www.southcentralmla.org South Central Modern Language Association University of Oklahoma 332 Cate Center Drive, Room 481 Norman, OK 73019-6410 Phone: (405) 325-6011 Fax: (405) 325-3720 Email: [email protected] Web: www.southcentralmla.org 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2015 Executive Committee ……………………………………………………………………. 3 Special Thanks ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Conference Hosts …………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Friends of SCMLA …………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Sustaining Departmental Members ……………………………………………………….. 7 SCMLA Life and Honorary Members ………………………………………………………. 8 Schedule of Events ………………………………………………………………………………… 9 Summary of Conference by Session Type …………………………………………….. 10 Conference Program ……………………………………………………………………………. 19 Grants, Awards and Prizes …………………………………………………………………….71 Grant and Prize Winners ……………………………………………………………………… 73 2016 SCMLA Deadlines ……………………………………………………………………….. 74 2 SCMLA 2015 Executive Committee Jeanne Gillespie, President University of Southern Mississippi [email protected] Melissa Bailar, Past President Rice University [email protected] Julie Chappell, Vice President Tarleton State University [email protected] Emily D. Johnson, Executive Director University of Oklahoma [email protected] Richard J. Golsan, Editor (2013-2017) South Central Review Texas -

HOOD, MARY. Mary Hood Papers, 1947-1995

HOOD, MARY. Mary Hood papers, 1947-1995 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Collection Stored Off-Site All or portions of this collection are housed off-site. Materials can still be requested but researchers should expect a delay of up to two business days for retrieval. Descriptive Summary Creator: Hood, Mary. Title: Mary Hood papers, 1947-1995 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 736 Extent: 12.75 linear feet (24 boxes) and 1 oversized papers folder (OP) Abstract: Papers of Georgia author Mary Hood including correspondence and personal papers, diaries, writings by Hood, and printed material. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Collection stored off-site. Researchers must contact the Rose Library in advance to access this collection. Diaries are closed to researchers. Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Special restrictions apply: The collection contains some copies of original materials held by other institutions; these copies may not be reproduced without the permission of the owner of the originals. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. -

BEYOND the PAGES University of Georgia Libraries

Volume 19 Spring 2014 BEYOND THE PAGES University of Georgia Libraries Visit the Libraries’ websites: www.libs.uga.edu UGA Libraries Contact Information Special Collections Library Dr. William Gray Potter University Librarian and www.libs.uga.edu/scl Associate Provost [email protected] Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library (706)542-0621 www.libs.uga.edu/hargrett Dr. Toby Graham Deputy University Librarian Director, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library Richard B. Russell Library for [email protected] Political Research and Studies (706) 583-0213 www.libs.uga.edu/russell Chantel Dunham Director of Development Walter J. Brown Media Archive [email protected] and Peabody Awards Collection (706) 542-0628 www.libs.uga.edu/media Leandra Nessel Development Officer Digital Library of Georgia [email protected] (706) 542-3879 www.dlg.galileo.usg.edu Ruta Abolins Director, Walter J. Brown Media Archives Cover Photo: and Peabody Awards Collection String musicians gather for a performance at WSB Radio. [email protected] M004_1288, WSB Radio Records, Popular Music and Culture (706) 542-4757 Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library. This photo was digitized as part of the Digital Sheryl B. Vogt Library of Georgia, which is based at the UGA Libraries. Director, Richard B. Russell Library for Political Research and Studies [email protected] (706) 542-0619 Sheila McAlister Director, Digital Library of Georgia [email protected] (706) 542-5418 Researchers | 706-542-7123 Events | 706-542-6331 Tours | 706-542-8079 Beyond The Pages is published twice annually by the University of Georgia Libraries. Editor: Leandra Nessel Writers: Steven Armour, Caroline Barratt, Carol Bishop, Jean Cleveland, Janine Duncan, Chantel Dunham, Callie Holmes, Patrick Kilbanoff, Jan Levinson, Greer Martin, Mary Miller, Leandra Nessel, Joe Samuel Starnes, Neal Warner Design: Jackie Baxter Roberts, UGA Press Articles may be reprinted with permission. -

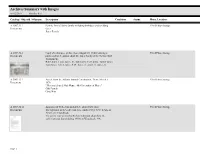

Archives Summary with Images 08/02/2019 Matches 651

Archives Summary with Images 08/02/2019 Matches 651 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description Condition Status Home Location A 2007.32.1 Family Tree of Jones family including birthdays and wedding Third Floor Storage Documents dates. Jones Family A 2007.32.2 Copy of newspaper picture from August 25, 1940 featuring a Third Floor Storage Documents photo and brief caption about the Jones family at the Canton Golf Tournament. Rube Jones, Louis Jones, Jr., Bob Jones, Tyre Jones, Turner Jones, Tom Jones, Albert Jones, P.W. Jones, Jr., and L.L. Jones, Sr. A 2007.33.1 Article from the Atlanta Journal Constitution, Thurs. March 5, Third Floor Storage Document 1970 "Sherman Spared Galt House: 4th Generation at Home" Galt Family Civil War A 2007.34.66 Appraisal of Collection and Article about Collection Third Floor Storage Documents The appraisal of the collection was conducted by Steve Lewis of American Arrowheads. The article was written by Richard Johnston about how the collection was found during 1930's in Woodstock, GA. Page 1 Catalog / Objectid / Objname Description Condition Status Home Location A 2007.35.1 Eight 8mm videotapes of interviews with local citizens including: Fourth Floor Storage Film Bill Hasty, Sr. Ben Ghorley Louis Jones, Jr. Glenn Tippens Magdalene G. Tippens Also shows a demonstration of a telegraph by Glenn Tippens. Filmed in the year 2003 A 2007.36.1 Letter written by Sam Tate, describing Tate house and subsequent Third Floor Storage Documents sale of property. Dated 1924. A 2008.7.1 US War Board Third Floor Storage Documents Authorization to begin construction forms for house located near intersection of Sixes and Noonday Church. -

Folklife 1996 Smithsonian Gardener Sung Do Kim Shows Orchids to Children at the National Museum of Natural History

American Folklife 1996 Smithsonian gardener Sung Do Kim shows orchids to children at the National Museum of Natural History. From: The Smithsonian: 1 50 Years of Adventure, Discovery, and Wonder by James Conaway, Smithsonian Books. Copyright © 19% Smithsonian Institution. Photo by Laurie IVIinor-Penland/SI Complimentary Copy SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Eestival of American Folklife 1996 June 26-30 & July 3-7 ON THE National Mall of the United States Washington, D.C. Iowa—Community Style The American South Working at the Smithsonian cosponsoredbythe National Park Service 1996 Festival of American Folklife On the cover Iowa — Community Style 7 Catherine HiebertKerst& RachelleH.Saltzman Community Matters in Iowa David M.Shribman Iowa: A Civic Place |^# f •^-^- A Taste of Thailand: Serving the "Publics" — Dan Hunter & Patrick McClintock .... •^llC^... Tom Morain RAGBRAI, the Des Moines Register's General Iowa Small Towns Annual Great Bicycle Ride Acwss Iowa, Information has become a grassroots festival on Services & Hours Small-Town Newspapers: wheels. Story on page 2 1. Iowa Communities in Print Participants Photo © David Thoreson — Jay Black Daily Schedules Horwitz Back cover Site Map Richard Hogs & the Meaning of Life in Iowa Contributors & Sponsors Iowa Women on the Farm Staff — Phyllis Carlin Friends of the Festival Rinzler Memorial Concert Chuck Offenburger A Rolling Festival in Iowa Smithsonian Folkways Recordings Don Wanatee Meskwaki Culture Mississippi master artist Hystercine Contents Cynthia Schmidt Rankin, who created this design she I. Michael Heyman They Sing, Dance & Remember: calls Sunburst, teaches quilting at 1996: Celebrations in Western Iowa IVlississippi Cultural Crossroads. A Year of Celebration .... Piioto © Roland L. Freeman Between the Rivers: Bruce Babbitt Previous page An Iowa Photo Album A Confluence of Heritage John Duccini maneuvers a hoop net on the National catching Mississippi catfish and for Watershed perch off the side of his boat. -

Everyday Ecologies in the Writings of Georgia Authors Tina Mcelroy Ansa, Melissa Fay Greene, Mary Hood, and Janisse Ray

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 12-15-2016 Everyday Ecologies in the Writings of Georgia Authors Tina McElroy Ansa, Melissa Fay Greene, Mary Hood, and Janisse Ray Rachel G. Wall Georgia Highlands College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Wall, Rachel G., "Everyday Ecologies in the Writings of Georgia Authors Tina McElroy Ansa, Melissa Fay Greene, Mary Hood, and Janisse Ray." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2016. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/168 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i EVERYDAY ECOLOGIES IN THE WRITINGS OF GEORGIA AUTHORS: TINA McELROY ANSA, MELISSA FAY GREENE, MARY HOOD, AND JANISSE RAY by RACHEL WALL Under the Direction of Pearl McHaney PhD. ABSTRACT “An ounce of action is worth a ton of theory.” –Ralph Waldo Emerson Four Georgia women authors focus on different but equally important components of life: the natural environment of Janisse Ray, relationships in Mary Hood, culture in Tina McElroy Ansa, and sociological history in Melissa Fay Greene. While the focus of the writings by these authors overlap, their various approaches examined together reveal the essential areas where contemporary society has lost its way. All four argue how not to live by pointing out examples of negative actions and the consequences of human carelessness. Through compelling stories, these four authors show us how to preserve and improve our environment, our relationships, our culture, and our history.