FIRST STEP ACT Approved Programs Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Practices Identified for Peer Support Programs

Best Practices Identified for Peer Support Programs Final January 2011 Identification of Best Practices in Peer Support: White Paper Authors: Nisha Money MD, MPH, ABIHM Monique Moore PhD David Brown PsyD Kathleen Kasper Jessica Roeder Paul Bartone PhD Mark Bates PhD Acknowledgement: LTC Phillip Holcombe PhD Kathi Hanna PhD Lauren Honess-Morreale MPH Snehal Patel MD Kathleen Sun Maj. Todd Yosick MSW Subject Matter Experts Interviewed: Moe Armstrong, Vet-to-Vet Col. James D. Bartolacci, Michigan National Guard, Buddy to Buddy Program Matthew Chinman, RAND Corporation, Department of Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh VISN-4 Mental Illness, Research, and Clinical Center Bill Genet, Police Organization Providing Peer Assistance, Inc. (POPPA) Lt. Col. Stéphane Grenier, Canadian Department of National Defense and Veterans Affairs Operational Stress Injury Social Support (OSISS) Program Richard Klomp, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Workforce and Responder Resiliency Team, Deployment Safety and Resiliency Team (DSRT) Dan O’Brien-Mazza, Veterans Health Administration, Mental Health Group Jon Wilson, California National Guard Peer-to-Peer Support Program Authors’ Positions at DCoE: Nisha N. Money MD, MPH, ABIHM, Chief Medical officer, Integrative Medicine, Resilience & Prevention (Resilience & Prevention directorate) Monique Moore PhD, Program Evaluation Development manager (Resilience & Prevention directorate) David G. Brown PsyD, chief Integrative Health Division (Provisional), (Resilience & Prevention directorate) Mark Bates, PhD, -

Principles of Community-Based Behavioral Health Services for Justice-Involved Individuals: a Research-Based Guide a Bridge to the Possible

Principles of Community-based Behavioral Health Services for Justice-involved Individuals: A Research-based Guide A bridge to the possible Acknowledgments This report was prepared for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) under contract number HHSS283201200058I/HHSS28342003T with SAMHSA, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Nainan Thomas served as contracting officer representative. Disclaimer The views, opinions, and content of this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of SAMHSA or HHS. Nothing in this document constitutes a direct or indirect endorsement by SAMHSA or HHS of any non-federal entity’s products, services, or policies, and any reference to non-federal entities’ products, services, or policies should not be construed as such. Public Domain Notice All material appearing in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission from SAMHSA. Citation of the source is appreciated. However, this publication may not be reproduced or distributed for a fee without the specific, written authorization of the Office of Communications, SAMHSA, HHS. Electronic Access and Printed Copies This publication may be downloaded or ordered at http://store.samhsa.gov or by calling SAMHSA at 1-877-SAMHSA-7 (1-877-726-4727). Recommended Citation Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Principles of Community-based Behavioral Health Services for Justice-involved Individuals: A Research-based Guide. HHS Publication No. SMA- 19-5097. Rockville, MD: Office of Policy, Planning, and Innovation. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019. Originating Office Office of Policy, Planning, and Innovation, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 5600 Fishers Lane, Rockville, MD 20857, HHS Publication No. -

Peer Support to Reduce Vicarious Trauma in Mental Health Providers

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) Projects College of Nursing 2020 Peer Support to Reduce Vicarious Trauma in Mental Health Providers Alina Kendrick Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/nursing_dnp_capstone Part of the Nursing Commons Kendrick, Alina, "Peer Support to Reduce Vicarious Trauma in Mental Health Providers" (2020). Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) Projects. 231. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/nursing_dnp_capstone/231 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Nursing at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: PEER SUPPORT FOR VICARIOUS TRAUMA 1 Peer Support to Reduce Vicarious Trauma in Mental Health Providers Alina Kendrick University of Massachusetts, Amherst College of Nursing DNP Project Chair: Gabrielle P Abelard, DNP, PMHNP, PMHCNS-BC, RN, BS DNP Project Mentor: Amanda Batterbee, MSN, PMHNP-BC Date of Submission: April 20, 2020 PEER SUPPORT FOR VICARIOUS TRAUMA 2 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................4 List of Tables Table 1: Professional Quality of Life Scale.............................................................21 Table 2: Secondary Traumatic Stress -

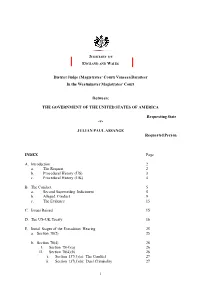

USA -V- Julian Assange Judgment

JUDICIARY OF ENGLAND AND WALES District Judge (Magistrates’ Court) Vanessa Baraitser In the Westminster Magistrates’ Court Between: THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Requesting State -v- JULIAN PAUL ASSANGE Requested Person INDEX Page A. Introduction 2 a. The Request 2 b. Procedural History (US) 3 c. Procedural History (UK) 4 B. The Conduct 5 a. Second Superseding Indictment 5 b. Alleged Conduct 9 c. The Evidence 15 C. Issues Raised 15 D. The US-UK Treaty 16 E. Initial Stages of the Extradition Hearing 25 a. Section 78(2) 25 b. Section 78(4) 26 I. Section 78(4)(a) 26 II. Section 78(4)(b) 26 i. Section 137(3)(a): The Conduct 27 ii. Section 137(3)(b): Dual Criminality 27 1 The first strand (count 2) 33 The second strand (counts 3-14,1,18) and Article 10 34 The third strand (counts 15-17, 1) and Article 10 43 The right to truth/ Necessity 50 iii. Section 137(3)(c): maximum sentence requirement 53 F. Bars to Extradition 53 a. Section 81 (Extraneous Considerations) 53 I. Section 81(a) 55 II. Section 81(b) 69 b. Section 82 (Passage of Time) 71 G. Human Rights 76 a. Article 6 84 b. Article 7 82 c. Article 10 88 H. Health – Section 91 92 a. Prison Conditions 93 I. Pre-Trial 93 II. Post-Trial 98 b. Psychiatric Evidence 101 I. The defence medical evidence 101 II. The US medical evidence 105 III. Findings on the medical evidence 108 c. The Turner Criteria 111 I. -

Peer-Based Addiction Recovery Support

Peer-based Addiction Recovery Support History, Theory, Practice, and Scientific Evaluation William L. White, MA Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Mental Retardation Services Dedication This monograph is dedicated to: Barbara Weiner and Rebecca Rowe of Hazelden Library, and to Stephanie Merkle and Christopher Roberts, research assistants at Chestnut Health Systems. This monograph was possible only through their tenacious efforts to procure hundreds of historical documents, scientific studies, trade journal articles, posted papers, conference presentations, and other unpublished manuscripts. Barbara, Rebecca, Stephanie and Christopher, and their counterparts around the country receive far less acknowledgment for their contributions to the field than they deserve. Thomasina Borkman, for her pioneering work on experiential learning and peer-based recovery support organizations. Those working on the front lines of peer-based addiction recovery support services. Thank you for opening your lives and your organizations to me. i ii Table of Contents Welcome from Lonnetta Albright and Michael Flaherty, PhD ................................ 1 Foreword by Arthur C. Evans, PhD and Beverly J. Haberle, MHS........................ 3 Abstract .................................................................................................................. 7 Introduction Summary of Key Points.......................................................................................... 9 The Recovery -

Chapter 3. Peer Support Fundamentals

CHAPTER PEER SUPPORT FUNDAMENTALS 3 Peer support does not adhere to any one “program model.” Rather, it is a dynamic and flexible approach A NATURAL HUMAN RESPONSE to connection and mutual understanding based on a set TO SHARED ADVERSITY of core values and principles. This chapter will present Most people who’ve been through hard information on the fundamentals of peer support that times empathize with and have an urge have been developed over the years by people who to reach out to others who struggle with have worked in peer support roles, conducted research problems that feel similar to their own. For on the topic, and have reflected upon and written about example, an older woman with children it.1,2,3,4 These ideas can be applied to any setting or shares her experiences with an over- activity. Understanding the fundamentals will help whelmed new mother. A widow offers tea you use the strategies presented in later chapters to and words of comfort to a woman whose apply these principles to peer support relationships husband has recently died. The desire for with women who are trauma survivors. The chapter peer support relationships can be seen also suggests books, articles, and websites that provide as a natural human response to shared additional information. struggles. What is Peer Support? Peer support is a way for people from diverse A “peer” is an equal, someone who has faced similar backgrounds who share experiences in common to circumstances, such as people who have survived come together to build relationships in which they cancer, widows, or women who parent adolescents. -

Staying Connected Is Important: Virtual Recovery Resources

STAYING CONNECTED IS IMPORTANT: VIRTUAL RECOVERY RESOURCES • Refuge Recovery: Provides online and virtual INTRODUCTION support In an infectious disease outbreak, when social https://www.refugerecovery.org/home distancing and self-quarantine are needed to • Self-Management and Recovery Training limit and control the spread of the disease, (SMART) Recovery: Offers global community continued social connectedness to maintain of mutual-support groups, forums including a recovery is critically important. Virtual chat room and message board resources can and should be used during this https://www.smartrecovery.org/community/ time. Even after a pandemic, virtual support may still exist and still be necessary. • SoberCity: Offers an online support and recovery community This tip sheet describes resources that can be https://www.soberocity.com/ used to virtually support recovery from mental/ substance use disorders as well as other • Sobergrid: Offers an online platform to help resources. anyone get sober and stay sober https://www.sobergrid.com/ • Soberistas: Provides a women-only VIRTUAL RECOVERY PROGRAMS international online recovery community https://soberistas.com/ • Alcoholics Anonymous: Offers online support • Sober Recovery: Provides an online forum for https://aa-intergroup.org/ those in recovery and their friends and family https://www.soberrecovery.com/forums/ • Cocaine Anonymous: Offers online support and services • We Connect Recovery: Provides daily online https://www.ca-online.org/ recovery groups for those with substance use and -

The Therapeutic Community As an Adaptable Treatment Modality Across Different Settings

P1: KEG Psychiatric Quarterly [psaq] ph259-psaq-482367 June 3, 2004 10:30 Style file version June 4th, 2002 Psychiatric Quarterly, Vol. 75, No. 3, Fall 2004 (C 2004) THE THERAPEUTIC COMMUNITY AS AN ADAPTABLE TREATMENT MODALITY ACROSS DIFFERENT SETTINGS David Kennard Simple core statements of the therapeutic community as a treatment modal- ity are given, including a “living-learning situation” and “culture of enquiry.” Applications are described in work with children and adolescents, chronic and acute psychoses, offenders, and learning disabilities. In each area the evolu- tion of different therapeutic community models is outlined. In work with young people the work of Homer Lane and David Wills is highlighted. For long term psychosis services, the early influence of “moral treatment” is linked to the revitalisation of asylums and the creation of community based facilities; acute psychosis services have been have been run as therapeutic communities in both hospital wards and as alternatives to hospitalisation. Applications in prison are illustrated through an account of Grendon prison. The paper also outlines the geographical spread of therapeutic communities across many countries. KEY WORDS: therapeutic communities; children; psychosis; prison; learning disability. The author is Head of Psychological Services, The Retreat, York, England. Address correspondence to David Kennard, The Retreat, York, YO10 5BN, United Kingdom; e-mail: [email protected]. 295 0033-2720/04/0900-0295/0 C 2004 Human Sciences Press, Inc. P1: KEG Psychiatric Quarterly [psaq] ph259-psaq-482367 June 3, 2004 10:30 Style file version June 4th, 2002 296 PSYCHIATRIC QUARTERLY This is a paper about different adaptations of the basic therapeutic community idea. -

Julian Assange Judgment

JUDICIARY OF ENGLAND AND WALES District Judge (Magistrates’ Court) Vanessa Baraitser In the Westminster Magistrates’ Court Between: THE GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Requesting State -v- JULIAN PAUL ASSANGE Requested Person INDEX Page A. Introduction 2 a. The Request 2 b. Procedural History (US) 3 c. Procedural History (UK) 4 B. The Conduct 5 a. Second Superseding Indictment 5 b. Alleged Conduct 9 c. The Evidence 15 C. Issues Raised 15 D. The US-UK Treaty 16 E. Initial Stages of the Extradition Hearing 25 a. Section 78(2) 25 b. Section 78(4) 26 I. Section 78(4)(a) 26 II. Section 78(4)(b) 26 i. Section 137(3)(a): The Conduct 27 ii. Section 137(3)(b): Dual Criminality 27 1 The first strand (count 2) 33 The second strand (counts 3-14,1,18) and Article 10 34 The third strand (counts 15-17, 1) and Article 10 43 The right to truth/ Necessity 50 iii. Section 137(3)(c): maximum sentence requirement 53 F. Bars to Extradition 53 a. Section 81 (Extraneous Considerations) 53 I. Section 81(a) 55 II. Section 81(b) 69 b. Section 82 (Passage of Time) 71 G. Human Rights 76 a. Article 6 84 b. Article 7 82 c. Article 10 88 H. Health – Section 91 92 a. Prison Conditions 93 I. Pre-Trial 93 II. Post-Trial 98 b. Psychiatric Evidence 101 I. The defence medical evidence 101 II. The US medical evidence 105 III. Findings on the medical evidence 108 c. The Turner Criteria 111 I. -

Peer Support in Centers for Independent Living: What Do We Know?

June 2011 Peer Support in Centers for Independent Living: What Do We Know? Peer support is ubiquitous. It is defined as a helping relationship between an individual who has experience living under certain conditions assisting another person to cope with and adapt to similar circumstances. It has been gaining in popularity and use since its early adoption in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), and has been used widely, and with good effect, with people experiencing a variety of both physical and mental health conditions. Peer support, also known as peer counseling, is one of the four core services that Independent Living Centers receiving funding from Part B, Title VII of the Rehabilitation Act of 1978 are mandated to provide. These services help a person with a disability move from the patient role to the consumer role, empowered to make independent choices (DeJong, 1979). Additionally, peer support assists people with similar disabilities to cope and adjust following the onset or exacerbation of a disability. Even more, peers often have intimate knowledge of community resources to reduce environmental barriers to independent living, which are essential to the Independent Living (IL) philosophy of consumer choice and control. Due in large part to the stress of living with a disability (i.e., lack of accessibility or accommodations), people with disabilities may experience mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety. Unfortunately, the mental health system in the US has struggled to meet the needs of people with psychiatric disabilities and is largely ill-prepared and underfunded to RTC:Rural address the mental health needs of individuals with other 52 Corbin Hall disabilities. -

Congressional Record—Senate S4732

S4732 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE April 27, 2009 lights to go on when we flip a switch, and we plant was being closed, more than 130 ‘‘Hopefully, when we obtain the power con- do not expect our computers to shut down as ALCOA employees accepted the company’s tract, it will just be a matter of waiting for nature dictates. severance package. Others were laid off—245 the market to pick up again. The good thing Solar and wind electricity are available hourly workers and 80 of the salaried work- about aluminum is that it is used in more only part of the time that consumers de- force. and more applications. It’s going to be mand power. Solar cells produce no electric The London Metal Exchange price for alu- around for a long time.’’ power at night, and clouds greatly reduce minum is half what it was one year ago, so their output. The wind doesn’t blow at a con- prospects for any immediate change is nil. f stant rate, and sometimes it does not blow The demand for the 1.3 million pounds of GUANTANAMO BAY at all. molten metal that the smelting plant can If large-scale electric energy storage were produce does not exist in the current mar- Mr. JOHANNS. Mr. President, I rise viable, solar and wind intermittency would ketplace. to speak about the detainment facili- be less of a problem. However, large-scale Still, leadership at the company is hopeful ties at Guantanamo Bay Naval Base. electric energy storage is possible only in that when the economy rebounds, Tennessee At the end of January of this year, the few locations where there are hydro- Smelting Operations will be in a position to be restarted. -

PAYING the PRICE for SOLITARY CONFINEMENT

PAYING the PRICE for SOLITARY CONFINEMENT Over the past few decades, United States corrections How Much More Does It Cost? systems have increasingly relied on the use of solitary The high costs of solitary confinement have been confinement as a tool to manage certain incarcerated documented by many states as well as the federal populations. Prisoners in solitary confinement remain government. Below are some examples: alone in their cells for 22-24 hours per day – for months, years, and even decades at a time. This practice, which States: has been shown to be inhumane and ineffective, is also • Arizona: A 2007 estimate from Arizona put the extremely costly. Though limited nationwide data exists, annual cost of holding a prisoner in solitary state data suggests that the cost of housing a prisoner in confinement at approximately $50,000, compared solitary confinement is 2-3 times that of housing a to about $20,000 for the average prisoner.5 1 prisoner in general population. • California: For 2010-2011, inmates in isolation at Pelican Bay State Prison’s Administrative Why is Solitary More Expensive? Segregation Unit cost $77,740 annually, while inmates in general population cost $58,324.6 Holding prisoners in solitary confinement is resource- Statewide, taxpayers pay an additional $175 intensive from start to finish. Below are two of the biggest million annually to keep prisoners in solitary costs associated with the use of solitary confinement. confinement.7 Construction: To accommodate the vast numbers of • Connecticut: In Connecticut, housing a prisoner in prisoners kept in solitary confinement, a new kind of solitary confinement costs an average of twice as prison has emerged.