Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Group Protests Marine Presence , Qu.Wiidnesday, Jan

73. Vol. ,23, Issue 16 THE TRINITY February t£ 1975 Trinity College TRIPOD Hartford, Conn. Student Elections Fill 12 College Committees Student elections were held last Fred Lahey 55 Thursday, Jan. 30, in the lobby of Mather Policy Board (1) Mather Hall. Twenty-three Kim Jonas 28 (write-in* positions on 12 college committees Special Committee on FU»ap» were filled by the winning can- pointment, Tenure, and didates whose names and total Promotions (2) votes received appear below. Total Steve Kayman 127 voter turnout on election day was SheUa Driscoll 109 610. Student Activities Committee (3) Election Results Jim Cobbs 141 Academic Affairs Committee (1) Peter Pieragostini 141 Paul Sachs 176 Ramsay Gross 130 College Affairs Committee (1) Parking Appeals Board (3) Adrienne Mally 147 Stan Goldich 197 Curriculum Committee (1) Ralph Stone 172 Bill Levy 114 Craig Shields 156 Financial Affairs Committee (1) Studeiit Government Association Stan Goldich 159 Library Committee (1) Pat Heffernan 227 • George Stiffler 301 Sheila Driscoll 190 Mather Hall Board of Gover- Richard Chamberlain 140 nors— upperclass position (2) Barbara Husum 130 Mary Desmond 153 Bill O'Brien 117 Jay Morgan 148 Mather Hall Board of Gover- Trinity College Council (1) nors—freshman position (l) Mike Brown 19 (write-in) photo by Al Moore Reaction Mixed Group Protests Marine Presence , Qu.Wiidnesday, Jan. 29, an anti- hearing the parting words of a another location on campus. The tn&tmte {action led by Peter Jessop marine recruiter whom Margolis removal of the Marines might, '76 and John Bach, a 27 year old reported to have said, "I'll see you however, entail more than just a Hartford resident, distributed next year. -

Marygold Manor DJ List

Page 1 of 143 Marygold Manor 4974 songs, 12.9 days, 31.82 GB Name Artist Time Genre Take On Me A-ah 3:52 Pop (fast) Take On Me a-Ha 3:51 Rock Twenty Years Later Aaron Lines 4:46 Country Dancing Queen Abba 3:52 Disco Dancing Queen Abba 3:51 Disco Fernando ABBA 4:15 Rock/Pop Mamma Mia ABBA 3:29 Rock/Pop You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:30 Rock You Shook Me All Night Long AC/DC 3:31 Rock AC/DC Mix AC/DC 5:35 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap ACDC 3:51 Rock/Pop Thunderstruck ACDC 4:52 Rock Jailbreak ACDC 4:42 Rock/Pop New York Groove Ace Frehley 3:04 Rock/Pop All That She Wants (start @ :08) Ace Of Base 3:27 Dance (fast) Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 3:41 Dance (fast) The Sign Ace Of Base 3:09 Pop (fast) Wonderful Adam Ant 4:23 Rock Theme from Mission Impossible Adam Clayton/Larry Mull… 3:27 Soundtrack Ghost Town Adam Lambert 3:28 Pop (slow) Mad World Adam Lambert 3:04 Pop For Your Entertainment Adam Lambert 3:35 Dance (fast) Nirvana Adam Lambert 4:23 I Wanna Grow Old With You (edit) Adam Sandler 2:05 Pop (slow) I Wanna Grow Old With You (start @ 0:28) Adam Sandler 2:44 Pop (slow) Hello Adele 4:56 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop (slow) Chasing Pavements Adele 3:34 Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Make You Feel My Love Adele 3:32 Pop Rolling in the Deep Adele 3:48 Blue-eyed soul Marygold Manor Page 2 of 143 Name Artist Time Genre Someone Like You Adele 4:45 Blue-eyed soul Rumour Has It Adele 3:44 Pop (fast) Sweet Emotion Aerosmith 5:09 Rock (slow) I Don't Want To Miss A Thing (Cold Start) -

Problems with and Alternatives to Humanitarianism and Savior Narratives for Ethiopia and Rwanda

“A Puzzle Viewed From Within”: Problems with and Alternatives to Humanitarianism and Savior Narratives for Ethiopia and Rwanda by Mandy Ann Davis A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Comparative Literature) in The University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Frieda Ekotto, Chair Assistant Professor Omolade Adunbi Associate Professor Christi Merrill Associate Professor Miriam Ticktin, The New School Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to our son, Nelson, and Baby #2, who will make his or her appearance soon. You both inspire my work and make it all the more urgent. My dream is that you may carry this work forward, as well. ii Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to my committee, Omolade Adunbi, Christi Merrill, and Miriam Ticktin, and especially my chair, Frieda Ekotto, who has been with me throughout this journey. Thank you for all of your individual and collective advice and encouragement. Thanks also to the Department of Comparative Literature for allowing me the time and latitude to explore in many different directions. Thanks to the members of my cohort: Jeffrey for laughter and keeping me sane during our early years; Suphak for many discussions and encouragement that helped me stay on course; Corina for adding beauty to our lives and for the last-minute editing that strengthened the project immensely. To my family and my in-laws: thank you for your help and encouragement in getting here. To the many friends and colleagues recently who have helped me as I've sought a balance between being an academic and being a parent. -

Pop / Rock / Commercial Music Wed, 25 Aug 2021 21:09:33 +0000 Page 1

Pop / Rock / Commercial music www.redmoonrecords.com Artist Title ID Format Label Print Catalog N° Condition Price Note 10000 MANIACS The wishing chair 19160 1xLP Elektra Warner GER 960428-1 EX/EX 10,00 € RE 10CC Look hear? 1413 1xLP Warner USA BSK3442 EX+/VG 7,75 € PRO 10CC Live and let live 6546 2xLP Mercury USA SRM28600 EX/EX 18,00 € GF-CC Phonogram 10CC Good morning judge 8602 1x7" Mercury IT 6008025 VG/VG 2,60 € \Don't squeeze me like… Phonogram 10CC Bloody tourists 8975 1xLP Polydor USA PD-1-6161 EX/EX 7,75 € GF 10CC The original soundtrack 30074 1xLP Mercury Back to EU 0600753129586 M-/M- 15,00 € RE GF 180g black 13 ENGINES A blur to me now 1291 1xCD SBK rec. Capitol USA 7777962072 USED 8,00 € Original sticker attached on the cover 13 ENGINES Perpetual motion 6079 1xCD Atlantic EMI CAN 075678256929 USED 8,00 € machine 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says 2486 1xLP Buddah Helidon YU 6.23167AF EX-/VG+ 10,00 € Verty little woc COMPANY 1910 FRUITGUM Simon says-The best of 3541 1xCD Buddha BMG USA 886972424422 12,90 € COMPANY 1910 Fruitgum co. 2 CELLOS Live at Arena Zagreb 23685 1xDVD Masterworks Sony EU 0888837454193 10,90 € 2 UNLIMITED Edge of heaven (5 vers.) 7995 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558049 USED 3,00 € 2 UNLIMITED Wanna get up (4 vers.) 12897 1xCDs Byte rec. EU 5411585558001 USED 3,00 € 2K ***K the millennium (3 7873 1xCDs Blast first Mute EU 5016027601460 USED 3,10 € Sample copy tracks) 2PLAY So confused (5 tracks) 15229 1xCDs Sony EU NMI 674801 2 4,00 € Incl."Turn me on" 360 GRADI Ba ba bye (4 tracks) 6151 1xCDs Universal IT 156 762-2 -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Versions Title Artist Versions #1 Crush Garbage SC 1999 Prince PI SC #Selfie Chainsmokers SS 2 Become 1 Spice Girls DK MM SC (Can't Stop) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue SF 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue MR (Don't Take Her) She's All I Tracy Byrd MM 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden SF Got 2 Stars Camp Rock DI (I Don't Know Why) But I Clarence Frogman Henry MM 2 Step DJ Unk PH Do 2000 Miles Pretenders, The ZO (I'll Never Be) Maria Sandra SF 21 Guns Green Day QH SF Magdalena 21 Questions (Feat. Nate 50 Cent SC (Take Me Home) Country Toots & The Maytals SC Dogg) Roads 21st Century Breakdown Green Day MR SF (This Ain't) No Thinkin' Trace Adkins MM Thing 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard MR + 1 Martin Solveig SF 21st Century Girl Willow Smith SF '03 Bonnie & Clyde (Feat. Jay-Z SC 22 Lily Allen SF Beyonce) Taylor Swift MR SF ZP 1, 2 Step Ciara BH SC SF SI 23 (Feat. Miley Cyrus, Wiz Mike Will Made-It PH SP Khalifa And Juicy J) 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind SC 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band SG 10 Million People Example SF 24 Hours From Tulsa Gene Pitney MM 10 Minutes Until The Utilities UT 24-7 Kevon Edmonds SC Karaoke Starts (5 Min 24K Magic Bruno Mars MR SF Track) 24's Richgirl & Bun B PH 10 Seconds Jazmine Sullivan PH 25 Miles Edwin Starr SC 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys BS 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash SF 100 Percent Cowboy Jason Meadows PH 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago BS PI SC 100 Years Five For Fighting SC 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The MM SC SF 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris SC 26 Miles Four Preps, The SA 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters PI SC 29 Nights Danni Leigh SC 10000 Nights Alphabeat MR SF 29 Palms Robert Plant SC SF 10th Avenue Freeze Out Bruce Springsteen SG 3 Britney Spears CB MR PH 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan BS SC QH SF Len Barry DK 3 AM Matchbox 20 MM SC 1-2-3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

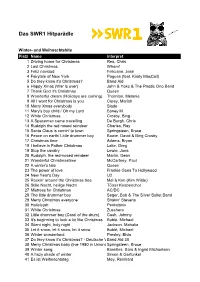

Das SWR1 Hitparädle

Das SWR1 Hitparädle Winter- und Weihnachtshits Platz Name Interpret 1 Driving home for Christmas Rea, Chris 2 Last Christmas Wham! 3 Feliz navidad Feliciano, José 4 Fairytale of New York Pogues (feat. Kirsty MacColl) 5 Do they know it's Christmas? Band Aid 6 Happy Xmas (War is over) John & Yoko & The Plastic Ono Band 7 Thank God it's Christmas Queen 8 Wonderful dream (Holidays are coming) Thornton, Melanie 9 All I want for Christmas is you Carey, Mariah 10 Merry Xmas everybody Slade 11 Mary's boy child / Oh my Lord Boney M. 12 White Christmas Crosby, Bing 13 A Spaceman came travelling De Burgh, Chris 14 Rudolph the red nosed reindeer Charles, Ray 15 Santa Claus is comin' to town Springsteen, Bruce 16 Peace on earth/ Little drummer boy Bowie, David & Bing Crosby 17 Christmas time Adams, Bryan 18 I believe in Father Christmas Lake, Greg 19 Stop the cavalry Lewie, Jona 20 Rudolph, the red-nosed reindeer Martin, Dean 21 Wonderful Christmastime McCartney, Paul 22 A winter's tale Queen 23 The power of love Frankie Goes To Hollywood 24 New Year's Day U2 25 Rockin' around the Christmas tree Mel & Kim (Kim Wilde) 26 Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht Tölzer Knabenchor 27 Mistress for Christmas AC/DC 28 The little drummer boy Seger, Bob & The Silver Bullet Band 29 Merry Christmas everyone Shakin' Stevens 30 Hallelujah Pentatonix 31 White Christmas Zucchero 32 Little drummer boy (Carol of the drum) Cash, Johnny 33 It's beginning to look a lot like Christmas Bublé, Michael 34 Silent night, holy night Jackson, Mahalia 35 Let it snow, let it snow, let it -

Karaoke Song Book Karaoke Nights Frankfurt’S #1 Karaoke

KARAOKE SONG BOOK KARAOKE NIGHTS FRANKFURT’S #1 KARAOKE SONGS BY TITLE THERE’S NO PARTY LIKE AN WAXY’S PARTY! Want to sing? Simply find a song and give it to our DJ or host! If the song isn’t in the book, just ask we may have it! We do get busy, so we may only be able to take 1 song! Sing, dance and be merry, but please take care of your belongings! Are you celebrating something? Let us know! Enjoying the party? Fancy trying out hosting or KJ (karaoke jockey)? Then speak to a member of our karaoke team. Most importantly grab a drink, be yourself and have fun! Contact [email protected] for any other information... YYOUOU AARERE THETHE GINGIN TOTO MY MY TONICTONIC A I L C S E P - S F - I S S H B I & R C - H S I P D S A - L B IRISH PUB A U - S R G E R S o'reilly's Englische Titel / English Songs 10CC 30H!3 & Ke$ha A Perfect Circle Donna Blah Blah Blah A Stranger Dreadlock Holiday My First Kiss Pet I'm Mandy 311 The Noose I'm Not In Love Beyond The Gray Sky A Tribe Called Quest Rubber Bullets 3Oh!3 & Katy Perry Can I Kick It Things We Do For Love Starstrukk A1 Wall Street Shuffle 3OH!3 & Ke$ha Caught In Middle 1910 Fruitgum Factory My First Kiss Caught In The Middle Simon Says 3T Everytime 1975 Anything Like A Rose Girls 4 Non Blondes Make It Good Robbers What's Up No More Sex.... -

Celebrating 40 Years of Commercial Radio With

01 Cover_v3_.27/06/1317:08Page1 CELEBRATING 40 YEARS OF COMMERCIAL RADIOWITHRADIOCENTRE OFCOMMERCIAL 40 YEARS CELEBRATING 01 9 776669 776136 03 Contents_v12_. 27/06/13 16:23 Page 1 40 YEARS OF MUSIC AND MIRTH CONTENTS 05. TIMELINE: t would be almost impossible to imagine A HISTORY OF Ia history of modern COMMERCIAL RADIO music without commercial radio - and FROM PRE-1973 TO vice-versa, of course. The impact of TODAY’S VERY privately-funded stations on pop, jazz, classical, soul, dance MODERN BUSINESS and many more genres has been nothing short of revolutionary, ever since the genome of commercial radio - the pirate 14. INTERVIEW: stations - moved in on the BBC’s territory in the 1960s, spurring Auntie to launch RADIOCENTRE’S Radio 1 and Radio 2 in hasty response. ANDREW HARRISON From that moment to this, independent radio in the UK has consistently supported ON THE ARQIVAS and exposed recording artists to the masses, despite a changing landscape for AND THE FUTURE broadcasters’ own businesses. “I’m delighted that Music Week 16. MUSIC: can be involved in celebrating the WHY COMMERCIAL RadioCentre’s Roll Of Honour” RADIO MATTERS Some say that the days of true ‘local-ness’ on the UK’s airwaves - regional radio for regional people, pioneered by 18. CHART: the likes of Les Ross and Alan Robson - are being superseded by all-powerful 40 UK NO.1 SINGLES national brands. If that’s true, support for the record industry remains reassuringly OVER 40 YEARS robust in both corners of the sector. I’m delighted that Music Week can be involved in celebrating the RadioCentre’s 22. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 09/04/2018 Sing Online on Entire Catalog

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 09/04/2018 Sing online on www.karafun.com Entire catalog TOP 50 Tennessee Whiskey - Chris Stapleton My Way - Frank Sinatra Wannabe - Spice Girls Perfect - Ed Sheeran Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Broken Halos - Chris Stapleton Sweet Caroline - Neil Diamond All Of Me - John Legend Sweet Child O'Mine - Guns N' Roses Don't Stop Believing - Journey Jackson - Johnny Cash Thinking Out Loud - Ed Sheeran Uptown Funk - Bruno Mars Wagon Wheel - Darius Rucker Neon Moon - Brooks & Dunn Friends In Low Places - Garth Brooks Fly Me To The Moon - Frank Sinatra Always On My Mind - Willie Nelson Girl Crush - Little Big Town Zombie - The Cranberries Ice Ice Baby - Vanilla Ice Folsom Prison Blues - Johnny Cash Piano Man - Billy Joel (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay - Otis Redding Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Turn The Page - Bob Seger Total Eclipse Of The Heart - Bonnie Tyler Ring Of Fire - Johnny Cash Me And Bobby McGee - Janis Joplin Man! I Feel Like A Woman! - Shania Twain Summer Nights - Grease House Of The Rising Sun - The Animals Strawberry Wine - Deana Carter Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley At Last - Etta James I Will Survive - Gloria Gaynor My Girl - The Temptations Killing Me Softly - The Fugees Jolene - Dolly Parton Before He Cheats - Carrie Underwood Amarillo By Morning - George Strait Love Shack - The B-52's Crazy - Patsy Cline I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys In Case You Didn't Know - Brett Young Let It Go - Idina Menzel These Boots Are Made For Walkin' - Nancy Sinatra Livin' On A Prayer - Bon -

Masarykova Univerzita V Brně Filozofická Fakulta

Masarykova univerzita v Brně Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Management v kultuře Michael Kořínek Kontext Band Aid, USA for Africa a Live Aid ve vývoji moderní populární hudby a absence vnímání tohoto kontextu v československém prostředí Magisterská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Aleš Opekar, CSc. 2014 Prohlášení: Prohlašuji, ţe jsem bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně s vyuţitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. …………………………………… II Poděkování: Panu PhDr. Aleši Opekarovi Csc. děkuji za všechny konzultace k této magisterské diplomové práci. Pánům doc. Ing. Vladimíru Hyánkovi, Ph.D. a Mgr. Bc. Jaroslavu Benákovi děkuji za konzultace a doporučení stran zdrojů a materiálů. Za odpověď a vyplnění emailového dotazníkového šetření děkuji: Heleně Burianové, Janě Jaruškové, Pavlu Stratilovi, Gabriele Štěpánkové a Jitce Václavkové III PŘEDMLUVA: ................................................................................................................................... 1 ÚVOD: ................................................................................................................................................. 1 HUMANITNÍ ODDÍL: ....................................................................................................................... 6 OSOBNOSTI CHARITATIVNÍCH NAHRÁVÁNÍ A KONCERTŮ: ......................................... 12 3.1 BOB GELDOF ............................................................................................................................. 12 3.2 BONO VOX ...............................................................................................................................