A Contribution to the Study of the Moral Practices of Certain Social

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

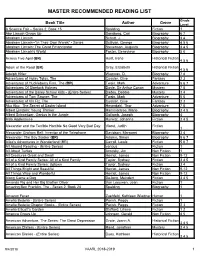

Master Recommended Reading List

MASTER RECOMMENDED READING LIST Grade Book Title Author Genre Level A Science Fair – Series 2, Book 15 Spalding Fiction 1 Abe Lincoln Grows Up Sandberg, Carl Biography 6 7 Abraham Lincoln Schott, J. Biography 3 4 Abraham Lincoln--"In Their Own Words" - Series Sullivan, George Biography 4 5 6 Abraham Lincoln: The Great Emancipator Stevenson, Augusta Biography 3 4 5 Abraham Lincoln's World Foster, Genevieve Biography 5 6 Across Five April (BR) Hunt, Irene Historical Fiction 4 5 6 Adam of the Road (BR) Gray, Elizabeth Historical Fiction 4 5 6 Adolph Hitler Wepman, D. Biography 7 8 Adventures of Hotsy Totsy, The Cussler, Clive Fantasy 2 3 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The (BR) Twain, Mark Adventure 5 6 7 Adventures Of Sherlock Holmes Doyle, Sir Arthur Conan Mystery 7 8 Adventures of the Bailey School Kids - (Entire Series) Dadey, Debbie Mystery 3 4 Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Twain, Mark Adventure 5 6 Adventures of Vin Fiz, The Cussler, Clive Fantasy 2 3 Aku Aku: The Secret of Easter Island Heyerdahl, Thor Adventure 7 8 Albert Einstein: Young Thinker Hammontree, Marie Biography 3 4 5 Albert Schweitzer, Genius in the Jungle Gollomb, Joseph Biography 4 Aldo Applesauce Hurwitz, Johanna Fiction 3 4 5 Alexander and the Terrible Horrible No Good Very Bad Day Viorst, Judith Fiction 1 Alexander Graham Bell: Inventor of the Telephone Davidson, Margaret Biography 3 4 Alexander: The Boy Soldier (BR) Adams, Simon Biography 5 6 7 Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (BR) Carroll, Lewis Fiction 5 6 7 All Aboard Reading - (Entire Series) various Fiction -

Thomas Hungerford

ADDITIONS AND CORRECTIONS FOR THOMAS HUNGERFORD OF HARTFORD AND NEW LONDON, CONN. AND HIS DESCENDANTS IN AMERICA By F. PHELPS LEACH Pitblished by F. PHELPS LEACH East Highgate, Vermont 1932 F"REI; PRESS PRINTING co.I BURLINGTOM1 VT, Copyright 1932 by F. PHELPS LEACH All rights reserved THE AUTHOR'S PREFACE The preparation of these additions and corrections for Thomas Hungerford of Hartford and New London, Conn., that I published in 1924, has been attended with no ordinary degree of perplexity and toil, on account of the imperfect and disordered condition of the records, and the necessity of resorting to various other sources for information. I have aimed at but two results-fullness and accuracy, but it is hardly to be expected that errors have been wholly avoided, and it is hoped that they are but few, and that they do not impair the usefulness of the work. I made two errors in my 1924 work which I have corrected in this, but the printers dropped type when they went to press, and were responsible for several. On page 14, in lines 35 and 38, they make the surname of the children of 5. Joseph Douglass7 Soule, Barnes instead of Soule. Mr. Soule married Mary Elizabeth Barnes. The first words that invite the eye in a book are the last written. When the preface is prepared the work is finished. Many lines in this volume are up-to-date, but the genealogy of the Hungerfords goes on. More great men of the name are to come. The logic of all genealogy contemplates the conclusion we confidently declare it is, that some day one of the descendants of this tribe will publish the 187 pages of manuscript of our English ancestors that I have before me. -

Report for 1923-1924 with the Supplement to the Guide to the Experimental Plots Containing the Yields Per Acre Etc

Report for 1923-1924 with the supplement to the Guide to the Experimental Plots containing the Yields per Acre etc. (1925) Thank you for using eradoc, a platform to publish electronic copies of the Rothamsted Documents. Your requested document has been scanned from original documents. If you find this document is not readible, or you suspect there are some problems, please let us know and we will correct that. Report for 1923-1924 With the Supplement to the Guide to the Experimental Plots Containing the Yields per Acre Etc. Full Table of Content Report for 1923-1924 With the Supplement to the Guide to the Experimental Plots Containing the Yields per Acre Etc. Report for 1923-1924 With the Supplement to the Guide to the Experimental Plots Containing the Yields per Acre Etc. (1925) Report For 1923-1924 With The Supplement To The Guide To The Experimental Plots Containing The Yields Per Acre Etc., pp -1 - 134 - DOI: https://doi.org/10.23637/ERADOC-1-116 - This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Report for 1923-1924 with the supplement pp 1 to the Guide to the Experimental Plots containing the Yields per Acre etc. Report for 1923-1924 with the supplement to the Guide to the Experimental Plots containing the Yields per Acre etc. (1925) f- 56. K^yg^ & Medical Serials |p*-^| LAWES AGRICULTURAL TRUST Rothamsted Experimental Station Harpenden REPORT 1923-24 with the Supplement to the "Guide to the Experimental Plots" containing The Yields per Acre, etc. V <^ $ To be obtained only of the Secretary Price 2j6 (Foreign Postage extra) Telephone and Telegrams Station Harpenden 21 Harpenden L.M.S HARPENDEN Printed by D. -

Sport & Celebr T & Celebr T & Celebr T

SporSportt && CelebrCelebrityity MemorMemorabiliaabilia inventory listing ** WE MAINLY JUST COLLECT & BUY ** BUT WILL ENTERTAIN OFFERS FOR ITEMS YOU’RE INTERESTED IN Please call or write: PO Box 494314 Port Charlotte, FL 33949 (941) 624-2254 As of: Aug 11, 2014 Cord Coslor :: private collection Index and directory of catalog contents PHOTOS 3 actors 72 signed Archive News magazines 3 authors 72 baseball players 3 cartoonists/artists 74 minor-league baseball 10 astronaughts 74 football players 11 boxers 74 basketball players 13 hockey players 74 sports officials & referrees 15 musicians 37 fighters: boxers, MMA, etc. 15 professional wrestlers 37 golf 15 track stars 37 auto racing 15 golfers 37 track & field 15 politicians 37 tennis 15 others 37 volleyball 15 “cut” signatures: from envelopes... 37 hockey 15 CARDS 76 soccer 16 gymnastics & other Olympics 16 minor league baseball cards 76 music 16 major league baseball cards 82 actors & models 19 basketball cards 97 other notable personalities 20 football cards 97 astronaughts 21 women’s pro baseball 98 politician’s photos 21 track, volleyball, etc., cards 99 signed artwork 24 racing cards 99 signed business cards 25 pro ‘rasslers’ 99 signed books, comics, etc. 25 golfers 99 other signed items 26 boxers 99 cancelled checks 27 hockey cards 99 baseball lineup cards 28 politicians 100 newspaper articles 28 musicians/singers 100 cachet envelopes 29 actors/actresses 100 computer-related items 29 others 100 other items- unsigned 29 LETTERS 102 uniforms & jerseys, etc. 30 major league baseball 102 PLATTERS MUSIC GROUP (ALL ITEMS) 31 minor league baseball 104 MULTIPLE SIGNATURES, 36 umpires 105 BALLS, PROGRAMS, ETC. -

![Catalogue Number [Of the Bulletin]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3138/catalogue-number-of-the-bulletin-4633138.webp)

Catalogue Number [Of the Bulletin]

\ \ WELLESLEY COLLEGE BULLETIN CATALOGUE NUMBER I95O-I95I WELLESLEY, MASSACHUSETTS Visitors to the College are welcome, and student guides are available. The adminis- trative offices in Green Hall are open Monday through Friday from 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. The Board of Admission office is open also on Saturday morning during the college year. Visitors to this office are advised to write in advance for an appointment. CATALOGUE NUMBER OF THE WELLESLEY COLLEGE BULLETIN OCTOBER XO, 1950 Bulletins published seven times a year by Wellesley College, Wellesloy, Massachusetts. April, threej September, one; October, two; November, one. Entered as second-class matter, December 20, 1911, at the Post Office at Wellesley, Massachusetts, under the Act of July 16, 1894. Additional entry a; Concord, N. H. Volume 40 Number 2 DIRECTIONS FOR CORRESPONDENCE In the list below are the administrative officers to whom inquiries of various types should be sent. The post office address is Wellesley 81, Massachusetts. General Policy of the College The President of Wellesley College Admission of Undergraduates The Director of Admission Applications for Readmission The Recorder Admission of Graduate Students The Chairman of the Committee on Graduate Instruction Inquiries Concerning Houses and Notice of Withdrawal The Dean of Residence Payment of College Bills The Assistant Treasurer (Checks should be made payable to Wellesley College) Scholarships The Dean of Students Academic Work of Students The Class Dean Social Regulations The Dean of Residence Requests for Transcripts of Records The Recorder Alumnae and Undergraduate Employment The Director of the Placement Office Requests for Catalogues The Information Bureau Alumnae Affairs The Executive Secretary of the Alumnae Association TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE page Calendar 5 Courses of Instruction.—Cont. -

Grade Two List Levels H Through M

Grade Two List Levels H through M Title Author Level Animal Tricks Wildsmith, Brain H Away Go the Boats Hillert, Margaret H Bailey Goes Camping Henkes, Kevin H Big Red Barn Brown, Margaret Wise H Busy Beavers Dabcovich, Lydia H Buzz, Buzz, Buzz Barton, Byron H Cake that Mack Ate, The Robart,Kovalski/Little Brown H Captain Cat Hoff, Syd H Cave Boy Dubowski, Cathy East H Clap your Hands Cauley, L H Clean House for Mole and Mouse Ziefert, Harriet H Come Out and Play Little Mouse Kraus, Robert H Curious George at the Beach Rey, Margaret H Danny and the Dinosaur Go to Hoff, Syd H Camp Dinosaur Who Lived in my Hennessy, B. G. H Backyard, the Enormous Turnip Slier, Debby H Enormous Watermelon, The Parkes, Brenda H George Shrinks Joyce, William H Gilberto and the Wind Ets, Marie Hall H Goodnight Moon Brown, Margaret Wise H Hanna's Butterfly Vinje, Marie H Hooray for the Golly sisters! Truesdell, Sue H How Do I put it on ? Watanabe, Shigeo H I Love Spiders Parker, John H I Was Walking Down the Road Barchas, S. Scholastic H Jafta Lewin, Hugh H Just Going to the Dentist Mayer, Mercer H Just Me and My Babysitter Mayer, Mercer H Just Me and My Dad Mayer, Mercer H Just Me and My Little Brother Mayer, Mercer H Just Me and My Little Sister Mayer, Mercer H Just Shopping with Mom Mayer, Mercer H Mama, Do You Love Me? Joosse, Barbara H My Mom Made Me Go to Camp Delton, Judy H New Baby Calf, The Chase, Edith & Reid H Owliver Kraus, Robert H Picture for Harold's Room, A Johnson, Crockett H Put Me in the Zoo Lopshire, Robert H Quack Said the Billy Goat Causley, Charles H Sammy the Seal Hoff, Syd H Seasons of Arnold's Apple Tree Gibbons, Gail H Sir Small and the Dragonfly O'Connor, Jane H Sleepy Book Brown, Margaret Wise H Small Pig Lobel, Arnold H There Was an Old Lady Who Adams, P. -

Proquest Dissertations

Lve's Ritual I he Judahite ^acred jV]arriage j\ite by ^tepnane fj)eaulieu Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-40814-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-40814-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. reproduced without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a la loi canadienne Privacy Act some supporting sur la protection de la vie privee, forms may have been removed quelques formulaires secondaires from this thesis. -

The Wellesley Legenda

r J 92 WELL :SLEY 1921 COPYRIGHT, 1921 BY Leslye Thomas wmmr B00t( I9ZI VELLE5LE? COLLEGE Page Dedication 8 Officers OK Administration AND Instrltction 11 History '21 The YoL'Nt; Student 2j SoiMiAL \\'hitless 43 ' Blab . 57 The Other Side of Paradise 67 The Legenda Cur 81 Senior Class Album . , 97 Class Lists 159 Graduate Students 194 Department of' Hygiene 196 Organizations /• • 19/ Publications 227 Societies 231 Piii I'jEta Kai>i>a 244 Clubs 246 Commencement Program 248 Advertisements 249 "to RosiQV^ru Kem> M.^mfyH'M^^M^y^'^e^^^l^: PRESIDENT PENDLETON Officers and Committees Board of Trustees Edwin Faknham Greene, B. A., F'rcsiticut of tl:c Board. Boston William Henry Lincoln, /'/(•(-/^r(\s-/(/r;(/ . Brooklinc Sarah Lawrence, Secretary. Boston Lewis Kennedy Morse, B. A.. LL. B., Treasurer . Boston William Fairfield W'arren, S T. D., LL. D.. Brooklinc Lilian Horsford Farlow Cambridge Edwin Hale Abbot, LL. B., Cambridge Louise McCoy North, M. A Madison. N. J. Andrew Fiske, Ph. D Boston George Edwin Horr, D. D., LL. D Neivton Centre George Howe Davenport Boston William Edwards Huntington, S. T. D., LL. D., Nexeton Centre \\ iLLiAM Blodget, B. A Clicstuut Hill Caroline Hazard, M. A.. Litt. D., LL. D., Peace Dale. R. I. George Herbert Palmer, M. A., I,itt. D., L. H. D., LL. D., Cambridge Eugene V. R. Thayer, B. .\ Nezc York Cit\< Galen L. Stone, Brooklinc I'.vLL Henry Hanus, S. B., LL. D Cambridge Candace Catherine Stimson, B. S. New York Citv Alice Upton Pearmain, M. A Bosto)i Belle Sherwin, B. S \\'illoughb\, O. -

Hoppy Summe? Readingl

Hoppy Summe? Readingl (book levels incresse with letter level) The First Grade Teachers All By Myself Mayer, Mercer 1.28 Big Egg Cox, Molly 1.28 Circus Fun Hillert, Margaret 1.28 Dog and Cat Fehner, Pauk t.28 Fire! Fire! Said Mrs.McGuire Martin, Bill 1.28 Five Little Monkeys...Jumping on the Bed Christelow, Eileen 1.28 Five Silly Fishermen Edwards, Roberta 1.28 Flying Crews, Donald 1.28 Foot Book, The Seuss, Dr. 1.28 Funny Man, A Jenson, Patricia 1.28 Get Lost Becka Simon, Shirley 1.28 Go, Dog, Go Eastman, Philip D. t.28 Goldilocks and the Three Bears Miles, Betty t.28 Gum on the Drum Start to Read 1.28 Happy Birthday, Dear Dragon Hillert, Margaret 1.28 Help for Dear Dragon Hillert, Margaret 1.28 Here Are My Hands Martin, Bill 1.28 Hi, Clouds Greene, Carol r.28 Hungry Billy Goat Milios, Rita et al: Rookie Reader 1.28 I Am Not a Dinosaur Packard, Mary t.28 I Like it When Murphy, Mary 1.28 I Love Cats Matthias, Catherine 1.28 If I Were an Ant Moses, Amy t.28 Inside, Outside, Upside down Berenstain, Stan & Jan 1.28 It Looked Like Spilt Milk Shaw, Charles 1.28 Just Like Me Neasi, Barbara 1.28 Larry and the Cookie McDaniel, Becky:Rookie Reader 1.28 Let's Go, Dear Dragon Hillert, Margaret 1.28 Little Cowboy and the Big Cowboy Hillert, Margaret 1.28 Little Runaway Hillert, Margaret t.28 Machines at Work Barton, Byron 1.28 Merry Christmas, Dear Dragon Hillert, Margaret 1.28 Mike's First Haircut Gordon, Sharon 1.28 Mike's New Bike Greydanus, R. -

Bryn Mawr College Annual Report , 1917-18. Bryn Mawr College

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Annual Reports of the President of Bryn Mawr Bryn Mawr College Publications, Special College Collections, Digitized Books 1918 Bryn Mawr College Annual Report , 1917-18. Bryn Mawr College Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_annualreports Part of the Liberal Studies Commons, and the Women's History Commons Citation Bryn Mawr College, "Bryn Mawr College Annual Report , 1917-18." (1918). Annual Reports of the President of Bryn Mawr College. Book 5. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_annualreports/5 This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_annualreports/5 For more information, please contact [email protected]. !l !<);!: m.-l'.:: iiiiiiit Bryn Mawr College Library Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/annualreportofpr05bryn Bryn Mawr College ANNUAL REPORT OF THE PRESIDENT 1917-18 *'^f^£~fM^^t0^^ Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania. Published by Bryn Mawr College. December, 1918. ()( ( I f;r I ff;l:/-.!' Corporation. Academic Year, 1917-18. RuFus M. Jones, President. Asa S. Wing, Anna Rhoadh Lauij, Treasurer. Secrctiirtj. RuFus M. Jones. Frederic H. Strawhridge. M. Carey Thomas. Abram F. Huston. Francis R. Cope, Jr. Anna Rhoads Ladd. Asa S. Wing. Arthur Henry Thomas. Charles J. Rhoads. William C. Dennis. Thomas Raeburn White. Arthur Perry. Arthur F. Chace. Board of Directors. Academic Year, 1917-18. RuFUs M. Jones, Chairman. Asa S. Wing, Anna Rhoads Ladd, Treasurer. -

Educational Directory 915-16

S. , . DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR--\, BUREAU OF EDUCATION BULLETIN,1 1 91 5, No:43 4.4 EDUCATIONAL DIRECTORY 915-16 c I *0 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 191S AIL 4 ADDITIONAL COPIES Or THIS PURIJCATION MAY Dr PROCIALD PRICY Till 80TIRINTZNDINT Or DOCUMINTS 00VIXATIKENT PIUITINOorici WAHHINOTON, D. C. AT ".20 CENTS PIER COPY 2 1.0 CONTENTS. Page. I Officers of the United States Bureau of Education 5 II. Principal State echoed officers 5 III. Officers of state boards of education 10 IV..Executive officers of State library commissions 11 V. Superintendents cities and towns of 2,500 population andover... 12 VI. Associate, assistant, and district superintendents in the largercities. 29 VII. County. superintendents 30 VIII. Township and district superintendents 51 XI. Officers of boards of trustees of universities and colleges or 59 X. University and college presidents 70 XI. Professors of pedagogy and heads, of departments ofpedagogy in universities and colleges 81 XI I. Presidents and deans of professional schools 85 X111. Principals of normal and kindergarten training sch x)Is 97 XIV. Superintendents of schools for the blind 104 XV. Superintendents of schools for the deaf 106 XVI. Superintendents of schools for the feeble-mindedv 107 XVII. Industrial education 109 XVIII. Directors of schools of art 115 XIX. Summer school directors 120 . XX. Directors of diuseurns.. 136 XXI. Librarians of public and'society libraries 148 XXII. Directors of library schools 168 XXIII. Educational boards and foundations 168 XIV. Church educational boards and societies 168 XXV. Superintendents of Catholic parochial echonls 169 XXVI. Jewish educational organizations 170 XXVII. -

Surplus Sale Clarkston School District Summer 2016

Surplus Sale Clarkston School District Summer 2016 Books from Parkway Elem: Title / Quantity Publisher Subject Grade Level Copyright Condition Dinosaurs 24 Houghton Mifflin Reading 4 1991 Obsolete Teacher's Manuals 2 Houghton Mifflin Reading 4 1991 Obsolete Mathematics 38 Silver Burdett Math 5 1988 Obsolete Holt Science 18 Holt Renehart Wilslow Science 4 1986 Obsolete Fast as the Wind 30 Houghton Mifflin Reading 5 1991 Obsolete *Also, teacher material for items above* tds 6/21/2016 APPROVED BY THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ON 6/28/2016 Parkway Elementary May 16, 2016 at 9:29 am Page 1 Discarded Copies (231) by Copy Call Number Alexandria 6.22.7 Selected: Discarded on Date 04/16/2016 - 05/16/2016 - Discarded by Patrons and from Inventory Barcode/ Title/ ISBN/ Site Call #/ Reason Discarded Cost Payment DISCARDED May 12, 2016 14.00 0.00 23744 - Tales from a not-so-dorky drama queen 9781442487697 PARK DISCARDED May 6, 2016 1.00 0.00 21407 - How do baby animals grow? 9781607190349 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 001.9 Taylor, D. Apr 27, 2016 12.95 0.00 4427 - Animal monsters : fantasies and facts of the animal world 0822521768 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 004 McA May 4, 2016 8.00 0.00 18719 - Working with computers 0836842421 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 004 RAU May 4, 2016 17.75 0.00 50745 - The history of the computer 1403496498 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 004.16 Kalbag, Asha May 5, 2016 22.96 0.00 14302 - Homework on your computer 074603346X Weeded PARK DISCARDED 004.16 Meredith, Susan May 5, 2016 22.96 0.00 14303 - Computers 0746034644 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 027 Gibbons, Gail May 5, 2016 89.15 0.00 12667 - Check it out : the book about libraries 0152164006 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 031 Clark, Rob Apr 27, 2016 7.95 0.00 8474 - Why 0516065947 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 031 Reece, C.