Tapestry of Tales: Stories of Self, Family, and Community Provide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancestor Scottsigler.Pdf

Extinction isn’t always a bad thing... Reviews for Ancestor “The future of gene manipulation is already here, and this ancestor may well be one of its outcomes. Be very, very afraid … or be extinct.” ~A.M. Stickel, BLACK PETALS MAGAZIN E “Sigler hits the rewind on evolution — and the fast-forward on action! Sigler’s beasties get their chomp on early and don’t let go: you can just feel the little Ancestors wriggling in the shadows of today’s biotech news stories, waiting to sink their primordial incisors deep into your spine.” ~Mark Jeffrey, author of THE POCKET & THE PENDANT “We’ve been told time and time again that it’s bad to play God. If Frankenstein and The Island of Dr. Moreau isn’t enough to convince you, then read Scott Sigler’s ANCESTOR. This is Robin Cook rewriting ALIENS. Strap yourself in for this intense warning of what genetic science can unleash. Prepare yourself for the ancestors.” ~Tee Morris, author of THE MOREVI SAGA “Scott Sigler writes like Michael Crichton in his prime, but edgier. Intensely addictive, ANCESTOR infects the imagination and races forward through a tail of genetic manipu- lation gone awry. As our primitive and savage ancestors are reborn, the body count rises and the pages keep turning. Intelligent, witty and scary as hell!” ~Jeremy Robinson, bestselling author of RAISING THE PAST “From ultra high-tech labs of bleeding edge biotech to snow-blinded islands haunted by our own genetic past, Scott Sigler takes you for a page-turning ride into real fear and adventure. -

Richard Marx Josh Turner Black Violin Chris White Tim Coffman Parsons

Tim Coffman Black Violin Photo Credit: Colin Brennan Josh Turner Richard Marx Photo Credit: Lois Greenfield Parsons Dance Chris White welcome to North Central College t’s time for another great season in the arts at ticket holder who said she was very happy to pick North Central College here in Naperville! We her own shows and didn’t have to give the tickets I are so excited to bring you another wonderful away to the shows when she was out of town. This season full of the best artists in the business. I is JUST what we were hoping would happen. suppose I could say sit back, relax and enjoy the I also want to thank our Friends of the Arts, the show, but in a way the only time we want you to sit angels who donate to the fine arts above and beyond back and relax is just before the show starts. We have the price of the tickets, and our corporate, hotel and such a terrific lineup this season that the excitement restaurant sponsors. You are making a difference will make it impossible to relax. So how about if I in our community. You understand how important say relax, save your energy because you are going the arts are to all of us and how they impact our to need it for the thunderous applause that you’re community. bound to give for whichever performer you came to see. Patrons come to our shows, they eat in Naperville restaurant, and stay in Naperville hotels. So, thank From Josh Turner to Richard Marx, Black Violin you for all you do, from the largest corporation to to Parsons Dance, Andy Williams Christmas the single donor. -

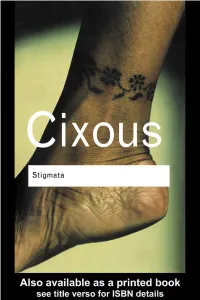

Stigmata: Escaping Texts

Stigmata ‘Hélène Cixous is in my eyes, today, the greatest writer in the French language… Stigmata is henceforth a classic…. One of her most recent masterpieces.’ Jacques Derrida Routledge Classics contains the very best of Routledge publishing over the past century or so, books that have, by popular consent, become established as classics in their field. Drawing on a fantastic heritage of innovative writing published by Routledge and its associated imprints, this series makes available in attractive, affordable form some of the most important works of modern times. For a complete list of titles visit http://www.routledgeclassics.com/ Hélène Cixous Stigmata Escaping texts With a foreword by Jacques Derrida and a new preface by the author London and New York First published 1998 by Routledge First published in Routledge Classics 2005 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge New York, NY 100 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge's collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” © 1998, 2005 Hélène Cixous Index compiled by Indexing Specialists (UK) Ltd, 202 Church Road, Hove, East Sussex BN3 2DJ, UK All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

April 17, 2017 2017 State Solo & Ensemble South Festival Schedule Dear Colleagues, How Wonderful to Work in an Area Where Th

April 17, 2017 2017 State Solo & Ensemble South Festival Schedule Dear colleagues, How wonderful to work in an area where there are so many talented music students! It is a credit to you that so many students attend this festival. It is your efforts, combined with that of the students (and in many cases, the private studio teachers), which produces such a packed schedule! At this point, no official changes to the schedule will be made. If there are emergencies, most adjudicators will be in the rooms by 8:30am and you may ask the adjudicators to allow you to perform before normal festival time begins. If necessary, you may also switch with another entry from within your school or another school. Track Meet at Orem High Orem High School will be hosting both the South State Solo & Ensemble Festival and the State Track Tiger Trials Meet. Because of this Bus parking will be particularly difficult. The Alpine District has requested that buses drop-off at the OHS Main Entrance and that they park at Scera Park Elementary Parking Lot to south of Orem High. Parking instructions are included on the map. Festival Operation Take a moment to familiarize yourself with the map of Orem High School. There will be information tables with schedules and maps throughout the buildings. The auxiliary gym will be available as a warm-up room equipped with a few electronic pianos. This room will open at 8:00am—since the majority of the festival doesn’t begin until 9:00am, this should leave the early entries plenty of time to warm-up. -

Strong Catholic Youth

Strong Catholic Families: Strong Catholic Youth Family Faith Resource Booklet “The ssiiinnggllle mmoosst iiimmppoorttaannt iiinnfluueenncce oon tthhe religious aannd ssppiiirriiittuuaal llliiivees oof aaddoollleesscceenntts iis tthheeiiir ppaarreenntts.” From Soul Searching, The Religious and Spiritual Lives of America’s Teenagers Dear Parents, Thank you for holding fast to the gift of faith. Your commitment to your children is a witness that you consider our Catholic faith to be a precious gift that must be intentionally passed on to the next generation. This task is not simple or easy, especially given all the stresses, busyness, and demands of our lives. The materials in this resource booklet are intended to help and support you in passing on this vital gift of faith. You are not alone. Parents all over this country are standing up to make their families and children stronger through faith. The NFCYM joins you and all parents as partners in growing strong Catholic children by building strong Catholic families. Your Partners in Faith at the National Federation for Catholic Youth Ministry www.nfcym.org This booklet is often used as part of the Strong Catholic Families: Strong Catholic Youth three-part training process for changing the way parishes partner with parents. It was developed by NFCYM and is presented in partnership with the National Conference for Catechetical Leadership (NCCL) and the National Association of Catholic Family Life Ministers (NACFLM). NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF Catholic Family Life Ministers Strong Catholic Families: Strong Catholic Youth Family Faith Resource Booklet Developmental Editor—Michael Theisen Publishing Coordinator—Kathleen Carver Layout and Graphic Design—Ruby Mikell National Federation for Catholic Youth Ministry, Inc., Washington, D.C. -

NEUEEUE EITUNG WWERRAERRA-Z-ZEITUNG Amtsblatt Der Gemeinde Gerstungen Gerstungen Mit Untersuhl * Lauchröden * Oberellen * Unterellen * Neustädt * Sallmannshausen

NNEUEEUE WWERRAERRA-Z-ZEITUNGEITUNG Amtsblatt der Gemeinde Gerstungen Gerstungen mit Untersuhl * Lauchröden * Oberellen * Unterellen * Neustädt * Sallmannshausen Jahrgang 18 Freitag, den 21. Mai 2010 Nummer 10 Ausgabe: 10/2010 Amtsblatt „Neue Werra-Zeitung“ Seite 2 Rufnummern und Öffnungszeiten Gemeindeverwaltung Gerstungen Burgmuseum Brandenburg Wilhelmstraße 53 Rufnummer ...................................036927/91735 oder 90619 99834 Gerstungen E-Mail: ...........................................info@die-brandenburg.de Tel.: ................................................................................245-0 Öffnungszeiten: Fax: .............................................................................245-50 April - September Sprechzeiten im Rathaus: Mittwoch und Freitag ..................................10:00 - 16:00 Uhr Montag: ..............................................................geschlossen Sonn-und Feiertage ...................................11:00 - 17:00 Uhr Dienstag: ..........................09.00 - 12.00 u. 14.00 - 18.00 Uhr Mittwoch: ............................................................geschlossen Wichtige Rufnummern und Öffnungszeiten Donnerstag: ......................09.00 - 12.00 u. 14.00 - 15.30 Uhr Freitag: .......................................................09.00 - 12.00 Uhr Polizei Notruf ....................................................................110 Sprechzeit des Bürgermeisters: Polizei-Sprechstunde in Gerstungen nur nach vorheriger telefonischer Vereinbarung KOBB Herr Schmidt, zu den -

Proper 23. October 11. 2020

Welcome to The Church of St. Paul in the Desert The Nineteenth Sunday after Pentecost Proper 23 Sunday, October 11, 2020, 10:30 am Our Mission Statements God has invited us to share the abundant life of Jesus Christ through the Church of St. Paul in the Desert by serving Christ in others and by gathering to praise and thank God in worship. We are a welcoming, empowering, supportive community. The Episcopal Diocese of San Diego is a missionary community that dares to follow Jesus Christ in his life of fearless love for the world. 125 West El Alameda, Palm Springs, CA 92262 ● 760.320.7488 ● www.stpaulsps.org 1 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two Prelude Pastorale, from Book II —Louis Vierne Welcome & Announcements The Word of God The Entrance Hymn #7 Christ whose glory fills the skies The people standing, the Celebrant says The Rev. Lorenzo Lebrija Blessed be God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. People Blessed be God’s kingdom, now and for ever. Amen. The Celebrant may say Almighty God, to you all hearts are open, all desires known, and from you no secrets are hid: Cleanse the thoughts of our hearts by the inspiration of your Holy Spirit, that we may perfectly love you, and worthily magnify your holy Name; through Christ our Lord. Amen. 2 The Hymn of Praise: Glory to God Gloria in excelsis 3 The Collect of the Day The Celebrant says to the people The Lord be with you. And also with you. Let us pray. The Celebrant says the Collect. Lord, we pray that your grace may always precede and follow us, that we may continually be given to good works; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and for ever. -

East African Perspectives of Family and Community, and How They Can Inform Western Ecclesiology Ben Strait [email protected]

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet M.A. in Family Ministry Christian Ministry 2016 East African Perspectives of Family and Community, and How They Can Inform Western Ecclesiology Ben Strait [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cmin_mafm Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, African Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, Practical Theology Commons, Regional Sociology Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Strait, Ben, "East African Perspectives of Family and Community, and How They aC n Inform Western Ecclesiology" (2016). M.A. in Family Ministry. 1. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cmin_mafm/1 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Christian Ministry at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in M.A. in Family Ministry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST AFRICAN PERSPECTIVES OF FAMILY AND COMMUNITY AND HOW THEY CAN INFORM WESTERN ECCLESIOLOGY BY BENJAMIN DAVID STRAIT M.A., Olivet Nazarene University, 2016 THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Family Ministry in the School of Graduate and Continuing Studies Olivet Nazarene University, 2016 Bourbonnais, Illinois OLIVET NAZARENE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND CONTINUING STUDIES -

January/February 1996

Your high school library can have a free subscription to ANIMAL PEOPLE–– Nonprofit the only independent newspaper covering all the news about animal protection. Organization Send your acceptance to: U.S. Postage ANIMAL PEOPLE, POB 205, Shushan, NY 12873, or fax it to 518-854-9601. Paid ANIMAL PEOPLE has no alignment or affiliation with any advocacy organization. ANIMAL PEOPLE, Out of cod, Canada tells fishers "kill seals" Inc. ST. JOHNS, Newfoundland––Blaming harp seals for a 99% decline in the mass of spawning cod off the Atlantic coast of POB 205, SHUSHAN, NY 12873 Newfoundland, Canadian Fisheries Minister Brian Tobin on [ADDRESS CORRECTION REQUESTED.] December 18 moved to appease out-of-work cod fishers in his home province by expanding the 1996 seal killing quota to 250,000––actually higher than many annual quotas during the peak years of the seal hunt in the 1970s and early 1980s. In effect resuming the all-out seal massacres that prompt- ed international protest until clubbing newborn whitecoats and hunting seals from large vessels was suspended in 1983, Tobin also pledged to maintain a bounty of about 15¢ U.S. per pound for each dead seal landed, and said he would encourage the revived use of large vessels to help sealers attack seal breeding colonies on offshore ice floes. rassed by an International Fund for Animal Welfare campaign The prohibition on killing whitecoats remains in effect, worldwide to expose the lack of market demand for seal products. but only means young seals will be killed not as newborns but as A report on seal marketing strategy commissioned by the Canadian two-week-old beaters, just beginning to molt and crawl. -

Ephemeral but Influential? the Correlation Between Facebook

healthcare Article Ephemeral But Influential? The Correlation between Facebook Stories Usage, Addiction, Narcissism, and Positive Affect Sen-Chi Yu 1,* and Hong-Ren Chen 2 1 Department of Counseling and Applied Psychology, National Taichung University of Education, Taichung City 40306, Taiwan 2 Department of Digital Content and Technology, National Taichung University of Education, Taichung City 40306, Taiwan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 8 September 2020; Accepted: 20 October 2020; Published: 26 October 2020 Abstract: Despite the steep increase in Facebook Stories users, there is scant research on this topic. This study compared the associations of frequency of Stories update, frequency of news feed updates, time spent reading Stories, and time spent reading news feeds, with regard to social media addiction, narcissism, and positive affect in college students. We recruited a sample of 316 college students from Taiwan. The analytical results show that Facebook Stories are more addictive and provoke more positive affect than conventional news feeds. Moreover, only usage behaviors associated with Stories predict narcissism. This study also found that the prediction of news feeds with regard to addiction, narcissism, and positive affect also seems to be diminishing and is being replaced by those of Stories. Future studies on the psychological consequences and predictors of social media usage should regard Stories as a crucial variable. Keywords: Facebook Stories; social media addiction; narcissism; positive affect 1. Introduction Facebook Stories are ephemeral, short user-generated photo and video collections that display shared content for a limited period of time [1]. Stories offer a news feed that relies on visual rather than written information. -

Independence

July 4 Events In County Throughout Cape May County, numerous celebrations will take place to mark the 236th anniversary of independence. Enjoy the day safely. Avalon The Fourth of July celebration will be high- lighted with a free patriotic concert presented by the Bay-Atlantic Symphony at 7 p.m.. The concert will be inside Avalon Community Hall, 30th Street and beach. No tickets are PUBLISHED EVERY WEDNESDAY BY THE SEAWAVE CORP. needed for this concert and seating will be Vol. 48 No. 27 Copyright 2010 Seawave Corp. All rights reserved. July 4, 2012 1508 Route 47, Rio Grande NJ 08242-1402 done on a fi rst-come, fi rst-served basis. This year’s concert is entitled “Quest and Delights of Freedom” and includes selections from Verdi, Anderson, Sousa, and Tchaik- ovsky. Dr. Herman J. Saatkamp Jr., president of the Richard Stockton College of New Jer- Independence sey, will serve as guest conductor. Immediately following concert the borough will present the largest fi reworks display along the New Jersey coastline at the 30th Street beach. The fi reworks begin at approximately Day 9:15 p.m. and will be set to patriotic music. A simulcast of the music accompanying the fi reworks will be broadcast live on WCZT 98.7 the Coast radio station. Before the fi reworks event, the Avalon Department of Recreation will have various fun kids’ activities on the Avalon beach, and next to Avalon Community Hall. Earlier in the day, Avalon will be holding its famous boat parade at high tide, starting at the Avalon Pointe Marina. -

Twenty Students Suspended for Myspace Page

TV Schedule Find Artists A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z # Home Music Shows News Movies, Games & More Search all MTV.com Mar 3 2006 10:45 AM EST Twenty Students Views 1,174 Suspended In Latest Send to Friend Round Of MySpace- Print Related Busts Drug and gun charges and two sexual-misconduct arrests also put the site in the spotlight this week. By Gil Kaufman Photo: MySpace.com As MySpace has exploded in popularity over the past two years and become the top TOP STORIES social networking site on the Internet for teens and twentysomethings, it has continued to draw attention from school administrators, police and politicians Kanye West, Radiohead, Rage Against the Machine, concerned over how some are using the site. Nine Inch Nails, Wilco Top Lollapalooza 2008 Lineup On Thursday, a student at TeWinkle Middle School in Costa Mesa, California, was Diddy Talks About L.A. Times' Tupac Story: 'It Just told he faces expulsion for allegedly posting graphic, anti-Semitic threats against a Really Hurt' classmate on his MySpace site, according to the The Los Angeles Times. 'American Idol' Castoff Ramiele Malubay On David Cook's Hospitalization: 'We All Break Down In School officials said 20 of his classmates were also suspended for viewing the Totally Different Ways' posting, and police are investigating the boy's comments as a possible hate crime. Parents of three of the suspended students said the invitation to join the boy's Kanye West Reveals Glow In The Dark Tour Stage Set, In The Newsroom Blog MySpace social group, which was named "I hate [girl's name]" followed by an anti- Semitic slur and an expletive, gave no indication of the alleged threat.