Scoping Report for the Croydon Local Plan Sustainability Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Auction of London Bus, Tram, Trolleybus & Underground

£5 when sold in paper format Available free by email upon application to: [email protected] An auction of London Bus, Tram, Trolleybus & Underground Collectables Enamel signs & plates, maps, posters, badges, destination blinds, timetables, tickets & other relics th Saturday 25 February 2017 at 11.00 am (viewing from 9am) to be held at THE CROYDON PARK HOTEL (Windsor Suite) 7 Altyre Road, Croydon CR9 5AA (close to East Croydon rail and tram station) Live bidding online at www.the-saleroom.com (additional fee applies) TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE Transport Auctions of London Ltd is hereinafter referred to as the Auctioneer and includes any person acting upon the Auctioneer's authority. 1. General Conditions of Sale a. All persons on the premises of, or at a venue hired or borrowed by, the Auctioneer are there at their own risk. b. Such persons shall have no claim against the Auctioneer in respect of any accident, injury or damage howsoever caused nor in respect of cancellation or postponement of the sale. c. The Auctioneer reserves the right of admission which will be by registration at the front desk. d. For security reasons, bags are not allowed in the viewing area and must be left at the front desk or cloakroom. e. Persons handling lots do so at their own risk and shall make good all loss or damage howsoever sustained, such estimate of cost to be assessed by the Auctioneer whose decision shall be final. 2. Catalogue a. The Auctioneer acts as agent only and shall not be responsible for any default on the part of a vendor or buyer. -

Diary June 2019.Rtf

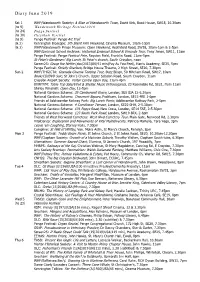

Diary June 2019 Sat 1 WHF/Wandsworth Society: A Slice of Wandsworth Town, David Kirk, Book House, SW18, 10.30am (to 9) Wandsworth Heritage Festival 2019 (to 24) Penge Festival (to 30) Caterham Festival (to 9) Penge Festival: Penge Art Trail (& 2) Kennington Bioscope: 5th Silent Film Weekend, Cinema Museum, 10am-10pm (& 2) WHF/Wandsworth Prison Museum: Open Weekend, Heathfield Road, SW18, 10am-1pm & 2-5pm WHF/Emanuel School Archives: Historical Emanuel School & Grounds Tour, Tony Jones, SW11, 11am Penge Festival: Penge Festival Fete, Royston Field, Franklin Road, 11am-5pm St Peter's Gardeners' Big Lunch, St Peter's church, South Croydon, noon Screen25: Grasp the Nettle (doc|2013|UK|91 min|Pay As You Feel), Harris Academy, SE25, 5pm Penge Festival: Strictly Sherlock, Bridge House Theatre, 2 High Street, SE20, 7.30pm Sun 2 WHF/THG/CTA: Granada Cinema Tooting Tour, Buzz Bingo, 50 Mitcham Road, SW17, 10am Book/CD/DVD Sale, St John’s Church, Upper Selsdon Road, South Croydon, 11am Croydon Airport Society: Visitor Centre Open Day, 11am-4pm BVWTVM: Table Top Sale/Vinyl & Shellac Music Extravaganza, 23 Rosendale Rd, SE21, from 11am Shirley Windmill: Open Day, 12-5pm National Gardens Scheme: 35 Camberwell Grove, London, SE5 8JA 12-6.30pm National Gardens Scheme: Choumert Square, Peckham, London, SE15 4RE 1-6pm Friends of Addiscombe Railway Park: Big Lunch Picnic, Addiscombe Railway Park, 2-5pm National Gardens Scheme: 4 Cornflower Terrace, London, SE22 0HH, 2-5.30pm National Gardens Scheme: 101 Pepys Road, New Cross, London, SE14 5SE, 2-5.30pm National Gardens Scheme: 123 South Park Road, London, SW19 8RX, 2-6pm Friends of West Norwood Cemetery: West Nwd Cemetery Tour, Main Gate, Norwood Rd, 2.30pm VitalDanza: Exploration and Movements of Vital Multidiversity, Patricia Martello, Tara Yoga, 3pm Leave 'em Laughing, Stanley Halls, 7.30pm Compline: St Hild of Whitby, Ven. -

Friends of Parks Groups

Friends of Parks Groups 1. Addington-Conservation-Team-ACT 2. Croydon Conservation Volunteers 3. Friends of Addiscombe Recreation Ground 4. Friends of Addiscombe Railway Park 5. Friends of Ashburton Park 6. Friends of Beulah Pond 7. Friends of Biggin Wood 8. Friends of Bradmore Green Pond 9. Friends of Coulsdon Coppice 10. Friends of Croham Hurst 11. Friends of Farthing Downs 12. Friends of Foxley 13. Friends of Grange Park 14. Friends of Grangewood Park 15. Friends of Haling Grove 16. Friends of Heavers Meadow 17. Friends of King's Wood 18. Friends of Littleheath Woods 19. Friends of Lloyd Park 20. Friends of Manor Farm 21. Friends of Marlpit Lane Bowling Green 22. Friends of Miller's Pond 23. Friends of Norbury Hall Park 24. Friends of Norbury Park 25. Friends of Park Hill Park 26. Friends of Purley Beeches 27. Friends of Rickman Hill 28. Friends of Sanderstead Recreation Ground 29. Friends of Selsdon Wood 30. Friends of South Croydon Recreation Ground 31. Friends of South Norwood Country Park 32. Friends of South Norwood Lake 33. Friends of Spa Wood 34. Friends of Spring Park Wood 35. Friends of Stambourne Woods 36. Friends of Thornton Heath Recreation Ground 37. Friends of Wandle Park 38. Friends of Westow Park 39. Friends of Wettern Tree Garden 40. Friends of Whitehorse Meadow 41. Heathfield Ecology Centre 42. Friends of Temple Avenue Copse 43. Friends of Whitehorse Road Recreation Ground 44. Hutchinson's and Brambly Bank volunteers 45. Heahtfield Ecology Centre 46. Sanderstead Plantation Partners, January 2021 Association of Croydon Conservation Societies Umbrella group for local nature conservation groups Friends of Parks, Woodlands and Green Spaces Forum Independent forum for all Croydon Friends of Park and Woodland Groups For contact details of groups without a web link please contact [email protected] January 2021 . -

REFERENDUMSUBMISSION VERSION (Regulation 186)

Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan Regulation 16 – draft Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan 2018 to 2033 Presented by the CR3 Neighbourhood Plan Group REFERENDUMSUBMISSION VERSION (Regulation 186) SEPTEMBERMAY 202019 Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan ReferendumSubmission (Regulation 186) Contents NB ‐ IN THIS TRACK CHANGE VERSION ORIGINAL CHAPTER, POLICY & FIGURE NUMBERS ARE SHOWN – THESE ARE AMENDED IN THE “CLEAN” VERSION. IGNORE PAGE NUMBERING. IN SOME PLACES FORMATTING IS ERRATIC. Add Foreword 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 43 National policy ...................................................................................................... 65 Local Policy .......................................................................................................... 65 Consultation ......................................................................................................... 76 2 LOCAL CONTEXT ............................................................................... 109 Profile of the community today ........................................................................... 1110 3 VISION AND OBJECTIVES .............................................................. 1312 Challenges for the Neighbourhood Plan Area ....................................................... 1312 Vision for the Neighbourhood Plan ...................................................................... 1312 Neighbourhood Plan Objectives -

Sustainability Appraisal for the Croydon Local

Sustainability Appraisal (SA) of the Croydon Local Plan Review Interim SA Report December 2019 Croydon Local Plan Review SA Interim SA Report Quality information Prepared by Checked by Verified by Approved by Chris McNulty, Mark Fessey, Steve Smith, Steve Smith, Senior consultant Associate Director Technical Director Technical Director Prepared for: London Borough of Croydon Prepared by: AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited Aldgate Tower 2 Leman Street London E1 8FA United Kingdom aecom.com © 2019 AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited. All Rights Reserved. This document has been prepared by AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“AECOM”) in accordance with its contract with London Borough of Croydon (the “Client”) and in accordance with generally accepted consultancy principles and the established budget. Any information provided by third parties and referred to herein has not been checked or verified by AECOM, unless otherwise expressly stated in the document. AECOM shall have no liability to any third party that makes use of or relies upon this document. AECOM Croydon Local Plan Review SA Interim SA Report Table of Contents Non-technical Summary .............................................................................................. i 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 2. What is the plan seeking to achieve? .............................................................. 2 3. What is the scope of the SA? ......................................................................... -

Impact of the Inspector's Recommendation on Local Green

Impact of the Inspector’s recommendation on Local Green Space The Inspector’s recommended main modification to the Croydon Local Plan to delete all Local Green Spaces has the following consequences. 2 Local Green Space continue to have protection as the Inspector has recommended that they become Metropolitan Open Land o Peabody Close playing field and allotments o Sanderstead Plantation 1 Local Green Space continues to have protection as it is a Listed Historic Park and Garden o Promenade du Verdun 8 Local Green Spaces continue to have some protection as they are locally listed Historic Parks and Gardens as well as Sites of Nature Conservation Importance o Beulah Hill Pond o Convent Wood o Duppas Hill o Haling Grove o Norbury Hall o Park Hill Recreation Ground o Upper Norwood Recreation Ground o Wandle Park 23 Local Green Spaces continue to have some protection as they are locally listed Historic Parks and Gardens o Addiscombe Recreation Ground o All Saints Churchyard, Sanderstead o All Saints with St Margaret's Churchyard o Ashburton Park o Beaulieu Heights o Chaldon Way Gardens o Coulsdon Memorial Ground o Grangewood Park o Millers Pond o Pollards Hill o Queen's Road Cemetery o Sanderstead Pond (and Green) o South Norwood Recreation Ground o St John's Church o St John's Church Memorial Garden o St Peter's Churchyard o The Lawns o The Queen's Gardens o Thornton Heath Recreation Ground o Wettern Green Garden o Whitehores Road Recreation Ground o Woodcote Village Green o Woodside Green 22 Local Green Spaces continue to have some protection -

Shirley Park Residents' Association

Miss C. E. RICHARDSON DP ROOFING D.Pod.M., M.Ch.S, S.R.Ch. & ASSOCIATES Shirley Park Specialist in Flat Roofing, Slating, Tiling STATE REGISTERED Residents’ CHIROPODISTS All Work Guaranteed Free Estimates Nursing/Residential Home service Association 1989-2010 30 Years Experience Minor Nail Surgery Home Visits For Housebound Newsletter — Election issue 2010 Tel: 0208 656 8708 Surgery consultations By appointment only Dave Patey Monday-Saturday Inclusive 45 Kingscote Road TEL: 020 8654 4670 Addiscombe 197A SHIRLEY RD. CROYDON Croydon Entrance in Valley Walk KN STAINED GLASS WALSH CONTAINERS Traditionally constructed CROYDON’S PREMIER stained glass windows and leaded lights SKIP COMPANY Old or damaged Over 30 years’ experience windows re-leaded Broken panels repaired MIDI AND MAXI SKIPS For advice Office 020 8656 7019 Or free estimate call: Mobile 07802 888 770 Keith Neiles Councillor Avril Slipper pays tribute to Lindsay Frost ON TIME EVERY TIME 32 Fernhurst Road Phone: 020 8656 6334 19 Ashburton Avenue Mobile: 07834 973 859 Addiscombe, Croydon, CRO 7JG An independent, non politically aligned organisation No job too small LICENSED WASTE CARRIER run for and by the residents of Addiscombe SPRA takes no responsibility for the services of any advert that appears in their newsletter. Denyer Printers Ltd. 33 Lower Road, Kenley, Surrey Telephone & Fax 020 8660 1375 Road Representatives Are you in pain? Addiscombe Road (275-393) Paul Pinder 28 Sefton Road Patricia West Annandale Road 5 Annandale Road Call in or telephone us. Ashburton Avenue Jacquie Farrow 51 Ashburton Avenue Ashling Road We are happy to answer your Ashurst Walk Shirley Vine 11 Ashurst Walk questions without obligation. -

BIKING BOROUGH STUDY LONDON BOROUGH of CROYDON Final

BIKING BOROUGH STUDY LONDON BOROUGH OF CROYDON Final Report July 2010 BIKING BOROUGH STUDY LONDON BOROUGH OF CROYDO N Final Report July 2010 Project Code: CROY -BB Prepared by: DB, CC, MM, MS Position: Various Approved by: DB, CC, MM, MS Issue Date: 5 July 2010 Status: ISSUE Biking Borough Study London Borough of Croydon Contents 1.0 Cycling in Croydon ………………………………..page 07 2.0 Ward Analysis ……………………………………..page 27 3.0 Current Borough Initiatives ………………………page 45 4.0 Cycling Hub Analysis ……………………………..page 60 5.0 Initiatives …………………………………………...page 70 6.0 Funding …………………………………………….page 83 7.0 Evaluation ………………………………………….page 91 8.0 Recommendations ………………………………..page 99 List of Tables Table 1 Cycling in Croydon & London, 2005/08 Table 16 MOSAIC Driver Segmentation by ward location 2010 Table 2 Comparison of cycle trip lengths in Croydon & London, Table 17 Croydon demographic overview 2010 2005/08 Table 3 Cycling frequency in Croydon, 2005/08 Table 18 MOSAIC Groups 1 demographic by ward 2010 Table 4 Cycling frequency by age band in Croydon, 2005/08 Table 19 MOSAIC Groups 2 demographic by ward 2010 Table 5 Cycling frequency by gender in Croydon, 2005/08 Table 20 Infrastructure initiatives Table 6 Cycling frequency by ethnic group in Croydon, 2005/08 Table 21 Smarter Travel initiatives Table 7 Cycling frequency by income group in Croydon, 2005/08 Table 22 Partnership initiatives Table 8 TfL automatic cycle count sites Table 23 Political initiatives Table 9 Potential cycleable trips in Croydon Table 24 Alignment of Infrastructure initiatives -

Official Guide & Street Plan 2015-2016

TAN_308206 FC Spread_spine.qxd 1/12/14 15:07 Page 1 TANDRIDGE TANDRIDGE Official Guide & Street Plan 2015-2016 Official Guide & Street TANDRIDGE Official Guide & Street Plan 2015-2016 TAN_308206 FC Spread_spine.qxd 1/12/14 15:07 Page 2 HOUSE PLANS DRAWN for your NEW BUILD EXTENSION, ROOF ROOM ANNEX, KITCHEN, EXTENSION, GARDEN STUDIO WHY MOVE WHEN YOU CAN CREATE SPACE & ADD VALUE TO YOUR EXISTING PROPERTY? We are a local architect practice based in Warlingham and provide design and planning services to obtain planning permission for domestic building projects, including new builds, home extensions and garden outbuildings. TREE FELLING, FENCING Contact us for a FREE visit and consultation to discuss your project. HEDGE CUTTING & DITCHING, Bob Mewies CHARTERED ENGINEER 07767 690331 SPRAYING, Forge Cottage, 55 Farleigh Road, Warlingham, Surrey CR6 9EJ SPORTS PITCH MAINTENANCE GROUND BREAKING Architectural Design Services OVER SEEDING www.bobmewies.com HARROW AND ROLLING, SLITTING/AERATING FERTILISING Best Buyer of any vehicle from £500 - £50,000 Part Exchanging Your Car? THE COTTAGE Been offered a poor trade in price? FRYERN FARM Why not give us a try? ROOK LANE We will try to improve your trade price. CHALDON CATERHAM Fast, friendly, professional service SURREY CR3 5AA money paid, same day instant bank transfer. Tel: CATERHAM (01883) 347881 Fax: CATERHAM (01883) 347443 01883 621348 www.paulmewies.co.uk 07970 600555 Email: [email protected] Mewies Ltd I Unit 1 I 79 Farleigh Road I Warlingham I Surrey CR6 9EJ 3034537 3033881 B/308206/11/14/ADV` -

FILE 1807 - KENT MAPS Nº 93/94 Cont'd from File Commencing 1801 Ending Map 92 LAURIE & WHITTLE 1806

FILE 1807 - KENT MAPS Nº 93/94 Cont'd from File commencing 1801 ending Map 92 LAURIE & WHITTLE 1806 93 CARY.J. Folio 1806 93/i Size-19" x 21.8"[.5"], 48.2cm x 55.2cm.[1.2cm] Upper L compass,Lower R scale within panel,'Scale 1.-8.Miles' =[2.3", 5.8cm]. Title 'A New Map of Kent....by John Cary.. 1806. Lower L a 4 column list of Lathes/Hundreds. Border tTt outer,dl graduated degrees L/L inner. obbc-' London.Published by J.Cary Engraver & Map-seller No 181,Strand July 1st, 1806.' 'Issued in 16 parts [Kent in Part 10],also flat sheet and folding 1806-9.Kent dated 1806. 'Cary's New English atlas;being a complete set...........' London J Cary 1809. (BL.Maps13 f16 / W.115 /NLS Newman 362 /Bir PL E 912 42 Skett 1 955834 / Bod A 67) Folding dissected copy.( Bod C 17: 36 e 4.) 93/ii. Add- new road 'Tunbridge Wells/Paddock Wood/Yalding'.'Thames & Medway Canal'. Map & Pi date still 1806. Folding dissected copy. 'Kent' [1809ii]. (Bir CL E 912 42 Skett 1-Ac 955834/RGS 1 B 97) 93/iii. Title '1811' & Pi'... April 28th.1811.. 'Cary's New English atlas;being a complete set...........' London J Cary 1811. (Bod Allen 74 & 75/RGS 1 B 98,folding copy RGS E&W S/D 122 ) 93/iv As above dating and add 'Royal Military Canal'. 'Cary's New English atlas;being a complete set...........' London J Cary 1811. ( BL 3055.[17] /BL Maps 13 f 18 /RGS 1 B 98 /W.115a /CUL 2 81 7) 93/v Title '1818' & Pi'.. -

Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan 2018 to 2033

Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan Adopted June 2021 Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan 2018 to 2033 Presented by the CR3 Neighbourhood Plan Group Adopted by Tandridge District Council June 2021 Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan Adopted June 2021 2 Caterham, Chaldon and Whyteleafe Neighbourhood Plan Adopted June 2021 (l to r) Chris Windridge, Jeremy Webster and Geoff Duck‐ leaders of the Neighbourhood Plan Steering Group between 2012 and 2020 Preface This Neighbourhood Plan has been in preparation for Nine Years. It is the second largest Plan in the Country (after Maidenhead). It is the only one, to date, which covers multiple parishes. Neighbourhood Plans must conform with development plans set by local authorities and not venture into areas that are the concern of other statutory bodies. However, it is a time of great change in Planning and Development. Neighbourhood Plans will play a crucial role in setting design standards to reflect local character and preferences about the form and appearance of development. Therefore, through the application of 29 policies, this plan seeks to: Define and protect neighbourhood character areas and promote development within them that respects their integrity. Preserve and enhance green spaces and corridors. Support the development of infrastructure and services Encourage business by promoting diversity of office and retail space. The Plan also offers protection to 22 Green Spaces and 34 views. It has been the intention throughout that the Plan will be owned by two village councils‐Chaldon and Whyteleafe and two parish councils, Caterham Hill and Valley. They have been united in their support of the Plan throughout its gestation and will now take on the task of monitoring its impact. -

Route Specifications 2016 South East South East Route March 2016 Network Rail –Route Specifications: South East 02

Delivering a better railway for a better Britain Route Specifications 2016 South East South East Route March 2016 Network Rail –Route Specifications: South East 02 Route A: Kent and High Speed One (HS1) Route B: Sussex In 2014, Network Rail merged the Kent and Sussex SRS A.01 Victoria Lines 4 SRS B.01 London Victoria - Windmill Bridge Junction 65 Route into South East Route. Kent and Sussex becoming Areas within the Route. SRS A.02 Otford - Sevenoaks 8 SRS B.02 Windmill Bridge Junction - Brighton 69 SRS A.03 London - Chislehurst 12 SRS B.03 London Bridge - Windmill Bridge Junction 73 To reflect this change, this document consists of Kent SRS A.04 Chislehurst - Tonbridge 16 SRS B.04 Three Bridges - Arundel Junction 77 and Sussex Areas in separate sections. SRS A.05 Chislehurst - Ashford 20 SRS B.05 Brighton - Havant 81 SRS A.06 Tonbridge - Hastings 24 SRS B.06 Brighton/Wivelsfield - Seaford/Hastings 85 The South East Route: Sussex Area Route Study Draft SRS A.07 Dartford lines to Gravesend & Hayes Branch 28 SRS B.07 South Central Inner Suburban 89 for Consultation was published in 2014 so this document will be updated in Summer 2015 when the SRS A.08 Bromley North Branch 32 SRS B.08 South Central Sutton Lines 93 Final document has been published. SRS A.09 Gravesend/Swanley - Margate 36 SRS B.09 Dorking - Horsham 97 SRS A.10 Sheerness Branch 40 SRS B.10 Hurst Green - Uckfield 101 SRS A.11 Strood - Paddock Wood 44 SRS B.11 Tattenham Corner and Caterham Lines 105 SRS A.12 East Kent Routes 48 SRS B.12 East Grinstead Line 109 SRS A.13 Hastings