Manifold Destiny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:1006.1489V2 [Math.GT] 8 Aug 2010 Ril.Ias Rfie Rmraigtesre Rils[14 Articles Survey the Reading from Profited Also I Article](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7077/arxiv-1006-1489v2-math-gt-8-aug-2010-ril-ias-r-e-rmraigtesre-rils-14-articles-survey-the-reading-from-pro-ted-also-i-article-77077.webp)

Arxiv:1006.1489V2 [Math.GT] 8 Aug 2010 Ril.Ias Rfie Rmraigtesre Rils[14 Articles Survey the Reading from Profited Also I Article

Pure and Applied Mathematics Quarterly Volume 8, Number 1 (Special Issue: In honor of F. Thomas Farrell and Lowell E. Jones, Part 1 of 2 ) 1—14, 2012 The Work of Tom Farrell and Lowell Jones in Topology and Geometry James F. Davis∗ Tom Farrell and Lowell Jones caused a paradigm shift in high-dimensional topology, away from the view that high-dimensional topology was, at its core, an algebraic subject, to the current view that geometry, dynamics, and analysis, as well as algebra, are key for classifying manifolds whose fundamental group is infinite. Their collaboration produced about fifty papers over a twenty-five year period. In this tribute for the special issue of Pure and Applied Mathematics Quarterly in their honor, I will survey some of the impact of their joint work and mention briefly their individual contributions – they have written about one hundred non-joint papers. 1 Setting the stage arXiv:1006.1489v2 [math.GT] 8 Aug 2010 In order to indicate the Farrell–Jones shift, it is necessary to describe the situation before the onset of their collaboration. This is intimidating – during the period of twenty-five years starting in the early fifties, manifold theory was perhaps the most active and dynamic area of mathematics. Any narrative will have omissions and be non-linear. Manifold theory deals with the classification of ∗I thank Shmuel Weinberger and Tom Farrell for their helpful comments on a draft of this article. I also profited from reading the survey articles [14] and [4]. 2 James F. Davis manifolds. There is an existence question – when is there a closed manifold within a particular homotopy type, and a uniqueness question, what is the classification of manifolds within a homotopy type? The fifties were the foundational decade of manifold theory. -

A MATHEMATICIAN's SURVIVAL GUIDE 1. an Algebra Teacher I

A MATHEMATICIAN’S SURVIVAL GUIDE PETER G. CASAZZA 1. An Algebra Teacher I could Understand Emmy award-winning journalist and bestselling author Cokie Roberts once said: As long as algebra is taught in school, there will be prayer in school. 1.1. An Object of Pride. Mathematician’s relationship with the general public most closely resembles “bipolar” disorder - at the same time they admire us and hate us. Almost everyone has had at least one bad experience with mathematics during some part of their education. Get into any taxi and tell the driver you are a mathematician and the response is predictable. First, there is silence while the driver relives his greatest nightmare - taking algebra. Next, you will hear the immortal words: “I was never any good at mathematics.” My response is: “I was never any good at being a taxi driver so I went into mathematics.” You can learn a lot from taxi drivers if you just don’t tell them you are a mathematician. Why get started on the wrong foot? The mathematician David Mumford put it: “I am accustomed, as a professional mathematician, to living in a sort of vacuum, surrounded by people who declare with an odd sort of pride that they are mathematically illiterate.” 1.2. A Balancing Act. The other most common response we get from the public is: “I can’t even balance my checkbook.” This reflects the fact that the public thinks that mathematics is basically just adding numbers. They have no idea what we really do. Because of the textbooks they studied, they think that all needed mathematics has already been discovered. -

Tōhoku Rick Jardine

INFERENCE / Vol. 1, No. 3 Tōhoku Rick Jardine he publication of Alexander Grothendieck’s learning led to great advances: the axiomatic description paper, “Sur quelques points d’algèbre homo- of homology theory, the theory of adjoint functors, and, of logique” (Some Aspects of Homological Algebra), course, the concepts introduced in Tōhoku.5 Tin the 1957 number of the Tōhoku Mathematical Journal, This great paper has elicited much by way of commen- was a turning point in homological algebra, algebraic tary, but Grothendieck’s motivations in writing it remain topology and algebraic geometry.1 The paper introduced obscure. In a letter to Serre, he wrote that he was making a ideas that are now fundamental; its language has with- systematic review of his thoughts on homological algebra.6 stood the test of time. It is still widely read today for the He did not say why, but the context suggests that he was clarity of its ideas and proofs. Mathematicians refer to it thinking about sheaf cohomology. He may have been think- simply as the Tōhoku paper. ing as he did, because he could. This is how many research One word is almost always enough—Tōhoku. projects in mathematics begin. The radical change in Gro- Grothendieck’s doctoral thesis was, by way of contrast, thendieck’s interests was best explained by Colin McLarty, on functional analysis.2 The thesis contained important who suggested that in 1953 or so, Serre inveigled Gro- results on the tensor products of topological vector spaces, thendieck into working on the Weil conjectures.7 The Weil and introduced mathematicians to the theory of nuclear conjectures were certainly well known within the Paris spaces. -

MY UNFORGETTABLE EARLY YEARS at the INSTITUTE Enstitüde Unutulmaz Erken Yıllarım

MY UNFORGETTABLE EARLY YEARS AT THE INSTITUTE Enstitüde Unutulmaz Erken Yıllarım Dinakar Ramakrishnan `And what was it like,’ I asked him, `meeting Eliot?’ `When he looked at you,’ he said, `it was like standing on a quay, watching the prow of the Queen Mary come towards you, very slowly.’ – from `Stern’ by Seamus Heaney in memory of Ted Hughes, about the time he met T.S.Eliot It was a fortunate stroke of serendipity for me to have been at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, twice during the nineteen eighties, first as a Post-doctoral member in 1982-83, and later as a Sloan Fellow in the Fall of 1986. I had the privilege of getting to know Robert Langlands at that time, and, needless to say, he has had a larger than life influence on me. It wasn’t like two ships passing in the night, but more like a rowboat feeling the waves of an oncoming ship. Langlands and I did not have many conversations, but each time we did, he would make a Zen like remark which took me a long time, at times months (or even years), to comprehend. Once or twice it even looked like he was commenting not on the question I posed, but on a tangential one; however, after much reflection, it became apparent that what he had said had an interesting bearing on what I had been wondering about, and it always provided a new take, at least to me, on the matter. Most importantly, to a beginner in the field like I was then, he was generous to a fault, always willing, whenever asked, to explain the subtle aspects of his own work. -

Exploring Curriculum Leadership Capacity-Building Through Biographical Narrative: a Currere Case Study

EXPLORING CURRICULUM LEADERSHIP CAPACITY-BUILDING THROUGH BIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE: A CURRERE CASE STUDY A dissertation submitted to the Kent State University College of Education, Health and Human Services in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Karl W. Martin August 2018 © Copyright, 2018 by Karl W. Martin All Rights Reserved ii MARTIN, KARL W., Ph.D., August 2018 Education, Health and Human Services EXPLORING CURRICULUM LEADERSHIP CAPACITY-BUILDING THROUGH BIOGRAPHICAL NARRATIVE: A CURRERE CASE STUDY (473 pp.) My dissertation joins a vibrant conversation with James G. Henderson and colleagues, curriculum workers involved with leadership envisioned and embodied in his Collegial Curriculum Leadership Process (CCLP). Their work, “embedded in dynamic, open-ended folding, is a recursive, multiphased process supporting educators with a particular vocational calling” (Henderson, 2017). The four key Deleuzian “folds” of the process explore “awakening” to become lead professionals for democratic ways of living, cultivating repertoires for a diversified, holistic pedagogy, engaging in critical self- examinations and critically appraising their professional artistry. In “reactivating” the lived experiences, scholarship, writing and vocational calling of a brilliant Greek and Latin scholar named Marya Barlowski, meanings will be constructed as engendered through biographical narrative and currere case study. Grounded in the curriculum leadership “map,” she represents an allegorical presence in the narrative. Allegory has always been connected to awakening, and awakening is a precursor for capacity-building. The research design (the precise way in which to study this ‘problem’) will be a combination of historical narrative and currere. This collecting and constructing of Her story speaks to how the vision of leadership isn’t completely new – threads of it are tied to the past. -

Campus Profile Sept 2018.Indd

CAMPUS PROFILE AND POINTS OF DISTINCTION campus profileOCTOBER 2018 CAMPUS PROFILE AND POINTS OF DISTINCTION At the University of California San Diego, we constantly push boundaries and challenge expectations. Established in 1960, UC San Diego has been shaped by exceptional scholars who aren’t afraid to take risks and redefine conventional wisdom. Today, as one of the top 15 research universities in the world, we are driving innovation and change to advance society, propel economic growth, and make our world a better place. UC San Diego’s main campus is located near the Pacific Ocean on 1,200 acres of coastal woodland in La Jolla, California. The campus sits on land formerly inhabited by Kumeyaay tribal members, the original native inhabitants of San Diego County. UC San Diego’s rich academic portfolio includes six undergraduate colleges, five academic divisions, and five graduate and professional schools. BY THE NUMBERS • 36,624 Total campus enrollment (as of Fall 2017); • 16 Number of Nobel laureates who have taught the largest number of students among colleges on campus and universities in San Diego County. • 201 Memberships held by current and emeriti • 97,670 Total freshman applications for 2018 faculty in the National Academy of Sciences (73), National Academy of Engineering (84), • 4.13 Admitted freshman average high school GPA and National Academy of Medicine (44). • $4.7 billion Fiscal year 2016-17 revenues; • 4 Scripps Institution of Oceanography operates 20 percent of this total is revenue from contracts three research vessels and an innovative Floating and grants, most of which is from the federal Instrument Platform (FLIP), enabling faculty, government for research. -

![Arxiv:2006.00374V4 [Math.GT] 28 May 2021](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6986/arxiv-2006-00374v4-math-gt-28-may-2021-176986.webp)

Arxiv:2006.00374V4 [Math.GT] 28 May 2021

CONTROLLED MATHER-THURSTON THEOREMS MICHAEL FREEDMAN ABSTRACT. Classical results of Milnor, Wood, Mather, and Thurston produce flat connections in surprising places. The Milnor-Wood inequality is for circle bundles over surfaces, whereas the Mather-Thurston Theorem is about cobording general manifold bundles to ones admitting a flat connection. The surprise comes from the close encounter with obstructions from Chern-Weil theory and other smooth obstructions such as the Bott classes and the Godbillion-Vey invariant. Contradic- tion is avoided because the structure groups for the positive results are larger than required for the obstructions, e.g. PSL(2,R) versus U(1) in the former case and C1 versus C2 in the latter. This paper adds two types of control strengthening the positive results: In many cases we are able to (1) refine the Mather-Thurston cobordism to a semi-s-cobordism (ssc) and (2) provide detail about how, and to what extent, transition functions must wander from an initial, small, structure group into a larger one. The motivation is to lay mathematical foundations for a physical program. The philosophy is that living in the IR we cannot expect to know, for a given bundle, if it has curvature or is flat, because we can’t resolve the fine scale topology which may be present in the base, introduced by a ssc, nor minute symmetry violating distortions of the fiber. Small scale, UV, “distortions” of the base topology and structure group allow flat connections to simulate curvature at larger scales. The goal is to find a duality under which curvature terms, such as Maxwell’s F F and Hilbert’s R dvol ∧ ∗ are replaced by an action which measures such “distortions.” In this view, curvature resultsR from renormalizing a discrete, group theoretic, structure. -

I. Overview of Activities, April, 2005-March, 2006 …

MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES RESEARCH INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2005-2006 I. Overview of Activities, April, 2005-March, 2006 …......……………………. 2 Innovations ………………………………………………………..... 2 Scientific Highlights …..…………………………………………… 4 MSRI Experiences ….……………………………………………… 6 II. Programs …………………………………………………………………….. 13 III. Workshops ……………………………………………………………………. 17 IV. Postdoctoral Fellows …………………………………………………………. 19 Papers by Postdoctoral Fellows …………………………………… 21 V. Mathematics Education and Awareness …...………………………………. 23 VI. Industrial Participation ...…………………………………………………… 26 VII. Future Programs …………………………………………………………….. 28 VIII. Collaborations ………………………………………………………………… 30 IX. Papers Reported by Members ………………………………………………. 35 X. Appendix - Final Reports ……………………………………………………. 45 Programs Workshops Summer Graduate Workshops MSRI Network Conferences MATHEMATICAL SCIENCES RESEARCH INSTITUTE ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2005-2006 I. Overview of Activities, April, 2005-March, 2006 This annual report covers MSRI projects and activities that have been concluded since the submission of the last report in May, 2005. This includes the Spring, 2005 semester programs, the 2005 summer graduate workshops, the Fall, 2005 programs and the January and February workshops of Spring, 2006. This report does not contain fiscal or demographic data. Those data will be submitted in the Fall, 2006 final report covering the completed fiscal 2006 year, based on audited financial reports. This report begins with a discussion of MSRI innovations undertaken this year, followed by highlights -

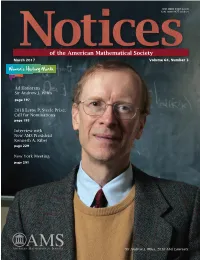

Sir Andrew J. Wiles

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 Volume 64, Number 3 Women's History Month Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Wiles page 197 2018 Leroy P. Steele Prize: Call for Nominations page 195 Interview with New AMS President Kenneth A. Ribet page 229 New York Meeting page 291 Sir Andrew J. Wiles, 2016 Abel Laureate. “The definition of a good mathematical problem is the mathematics it generates rather Notices than the problem itself.” of the American Mathematical Society March 2017 FEATURES 197 239229 26239 Ad Honorem Sir Andrew J. Interview with New The Graduate Student Wiles AMS President Kenneth Section Interview with Abel Laureate Sir A. Ribet Interview with Ryan Haskett Andrew J. Wiles by Martin Raussen and by Alexander Diaz-Lopez Allyn Jackson Christian Skau WHAT IS...an Elliptic Curve? Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof by by Harris B. Daniels and Álvaro Henri Darmon Lozano-Robledo The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles by Christopher Skinner In this issue we honor Sir Andrew J. Wiles, prover of Fermat's Last Theorem, recipient of the 2016 Abel Prize, and star of the NOVA video The Proof. We've got the official interview, reprinted from the newsletter of our friends in the European Mathematical Society; "Andrew Wiles's Marvelous Proof" by Henri Darmon; and a collection of articles on "The Mathematical Works of Andrew Wiles" assembled by guest editor Christopher Skinner. We welcome the new AMS president, Ken Ribet (another star of The Proof). Marcelo Viana, Director of IMPA in Rio, describes "Math in Brazil" on the eve of the upcoming IMO and ICM. -

Prospects in Topology

Annals of Mathematics Studies Number 138 Prospects in Topology PROCEEDINGS OF A CONFERENCE IN HONOR OF WILLIAM BROWDER edited by Frank Quinn PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 1995 Copyright © 1995 by Princeton University Press ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Annals of Mathematics Studies are edited by Luis A. Caffarelli, John N. Mather, and Elias M. Stein Princeton University Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources Printed in the United States of America by Princeton Academic Press 10 987654321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prospects in topology : proceedings of a conference in honor of W illiam Browder / Edited by Frank Quinn. p. cm. — (Annals of mathematics studies ; no. 138) Conference held Mar. 1994, at Princeton University. Includes bibliographical references. ISB N 0-691-02729-3 (alk. paper). — ISBN 0-691-02728-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Topology— Congresses. I. Browder, William. II. Quinn, F. (Frank), 1946- . III. Series. QA611.A1P76 1996 514— dc20 95-25751 The publisher would like to acknowledge the editor of this volume for providing the camera-ready copy from which this book was printed PROSPECTS IN TOPOLOGY F r a n k Q u in n , E d it o r Proceedings of a conference in honor of William Browder Princeton, March 1994 Contents Foreword..........................................................................................................vii Program of the conference ................................................................................ix Mathematical descendants of William Browder...............................................xi A. Adem and R. J. Milgram, The mod 2 cohomology rings of rank 3 simple groups are Cohen-Macaulay........................................................................3 A. -

Richard Schoen – Mathematics

Rolf Schock Prizes 2017 Photo: Private Photo: Richard Schoen Richard Schoen – Mathematics The Rolf Schock Prize in Mathematics 2017 is awarded to Richard Schoen, University of California, Irvine and Stanford University, USA, “for groundbreaking work in differential geometry and geometric analysis including the proof of the Yamabe conjecture, the positive mass conjecture, and the differentiable sphere theorem”. Richard Schoen holds professorships at University of California, Irvine and Stanford University, and is one of three vice-presidents of the American Mathematical Society. Schoen works in the field of geometric analysis. He is in fact together with Shing-Tung Yau one of the founders of the subject. Geometric analysis can be described as the study of geometry using non-linear partial differential equations. The developments in and around this field has transformed large parts of mathematics in striking ways. Examples include, gauge theory in 4-manifold topology, Floer homology and Gromov-Witten theory, and Ricci-and mean curvature flows. From the very beginning Schoen has produced very strong results in the area. His work is characterized by powerful technical strength and a clear vision of geometric relevance, as demonstrated by him being involved in the early stages of areas that later witnessed breakthroughs. Examples are his work with Uhlenbeck related to gauge theory and his work with Simon and Yau, and with Yau on estimates for minimal surfaces. Schoen has also established a number of well-known and classical results including the following: • The positive mass conjecture in general relativity: the ADM mass, which measures the deviation of the metric tensor from the imposed flat metric at infinity is non-negative. -

Committee to Select the Winner of the Veblen Prize

Committee to Select the Winner of the Veblen Prize General Description · Committee is standing · Number of members is three · A new committee is appointed for each award Principal Activities The award is made every three years at the Annual (January) Meeting, in a cycle including the years 2001, 2004, and so forth. The award is made for a notable research work in geometry or topology that has appeared in the last six years. The work must be published in a recognized, peer-reviewed venue. The committee recommends a winner and communicates this recommendation to the Secretary for approval by the Executive Committee of the Council. Past winners are listed in the November issue of the Notices in odd-numbered years. About this Prize This prize was established in 1961 in memory of Professor Oswald Veblen through a fund contributed by former students and colleagues. The fund was later doubled by a gift from Elizabeth Veblen, widow of Professor Veblen. In honor of her late father, John L. Synge, who knew and admired Oswald Veblen, Cathleen Synge Morawetz and her husband, Herbert, substantially increased the endowed fund in 2013. The award is supplemented by a Steele Prize from the AMS under the name of the Veblen Prize. The current prize amount is $5,000. Miscellaneous Information The business of this committee can be done by mail, electronic mail, or telephone, expenses which may be reimbursed by the Society. Note to the Chair Work done by committees on recurring problems may have value as precedent or work done may have historical interest.