Begin Tape Two, Side One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Let's Go for a Reading Walk

April 2015 Brookwood Elementary School Read-aloud favorites Let’s go for a reading walk ■ Up, Down, and Around (Katherine Ayres) It’s springtime—the perfect Corn grows up toward the time to go for a walk. Why not sky, but beets grow down make it a reading walk? Here into the ground. This are fun ways your child can nonfiction book intro- read words in her environ- duces your child to ment while you enjoy the plants and prepositions at the same outdoors together. time, as she sees the different direc- Match the card tions that vegetables grow. (Also Before heading out, help available in Spanish.) your youngster write words ■ Ellison the Elephant on index cards to match ones she might see. For a walk (Eric Drachman) downtown, she could write Ellison can’t produce main and sale or draw street a trumpet sound signs and store logos. If you’re like his sister or going to the park, her cards may include she can choose a different category. She his friends do. His words like trail and playground. As you could keep track of how many words she mother tries to reas- walk, have her search for each word, reads for each one and declare her most sure him that being different makes read it aloud, and hand the card to you. popular category! him special. But the other elephants Can she match all of her cards? tease him for the quiet toot that comes Spot little words out of his trunk. Includes a CD that Fit a category Encourage your youngster to look for lets children hear the “jazzy” sound Ask your child to think of a category little words within big ones—a strategy that Ellison learns to make. -

50 Years in Rock History

HISTORY AEROSMITH 50 YEARS IN ROCK PART THREE AEROSMITH 50 YEARS IN ROCK PART THREE 1995–1999 The year of 1995 is for AEROSMITH marked by AEROSMITH found themselves in a carousel the preparations of a new album, in which the of confusions, intrigues, great changes, drummer Joey Kramer did not participate in its termination of some collaboration, returns first phase. At that time, he was struggling with and new beginnings. They had already severe depressive states. After the death of his experienced all of it many times during their father, everything that had accumulated inside career before, but this time on a completely him throughout his life and could no longer be different level. The resumption of collaboration ignored, came to the surface. Unsuspecting and with their previous record company was an 2,000 miles away from the other members of encouragement and a guarantee of a better the band, he undergoes treatment. This was tomorrow for the band while facing unfavorable disrupted by the sudden news of recording circumstances. The change of record company the basics of a new album with a replacement was, of course, sweetened by a lucrative drummer. Longtime manager Tim Collins handled offer. Columbia / Sony valued AEROSMITH the situation in his way and tried to get rid of at $ 30 million and offered the musicians Joey Kramer without the band having any idea a contract that was certainly impossible about his actions. In general, he tried to keep the to reject. AEROSMITH returned under the musicians apart so that he had everything under wing of a record company that had stood total control. -

Paul Mccartney, 1980-1999

Paul McCartney from Wings through the 90's McCartney II Columbia FC‐36511 May 21, 1980 About ten years after recording McCartney by himself, Paul got several songs together and recorded them‐‐again alone‐‐on somewhat of a lark. Then Paul embarked on his ill‐fated 1980 tour of Japan (which resulted in his being jailed for drug possession). After returning to the safety of his own home, he was urged to release the album, and he did. The album contrasts well with McCartney, for this second production contains numerous instruments and electronic tricks that were not present on the 1970 release. Side One is particularly interesting. The solo version of "Coming Up" is followed by the fun track, "Temporary Secretary" (released as a single in England). The almost‐lament, "On the Way," is then succeeded by "Waterfalls," Paul's second (US) single from the album. "Bogey Music," from Side Two, is also a standout. John Lennon heard a song from McCartney II and thought that Paul sounded sad. When the album was released in the US, a bonus one‐sided single ‐‐ the hit version of "Coming Up"‐‐was included with the LP. This hit was enough to propel the album to the #3 position on the charts, during a time when disco was now on the wane. "Waterfalls" Columbia 1‐11335 Jul. 22, 1980 The lovely ballad about protectiveness was one of the standouts from McCartney II. After "Coming Up," it received the most airplay and the most positive response from Paul's friends. As a single, though, the song fared poorly, only reaching #83...one of Paul's worst showings to date. -

The Beatles Record Review

WRITING ASSIGNMENT Record Review You are going to write a record review of an album that is deemed significant in Rock Music. A list of groups/artists can be accessed by clicking on link below http://www.rollingstone.com/ news/story/5938174/the_rs_500_greatest_albums_of_all_time Criteria: Title Page Name, word count, course number, section number, etc. Introduction: Write a biography of the group you're critiquing. This should include the year the group/artist began recording, a list of and year of recordings, billboard chart positions, and any awards, Grammys, etc. www.allmusic.com is a great source for biographical information. Section 1 You will need to include all of the specifics of the recording, record label, producer(s), year, and dates of recording. Listen to the album several times as if you were a record critic and write an overview of the album, i.e. style of music, mood, highlights, lowlights, etc. Here are some things to consider: Is there a unifying theme throughout the album? Are there contrasting themes? If so, what are they? Is there enough variety musically in your opinion? What is it about this album in particular that makes it stand out? Section 2 Pick four songs and discuss them in more detail. Discuss your likes and dislikes as we have in relation to the journal entries in class but you will need to go into more detail. Discuss any other elements you find compelling, i.e., imagery from the lyrics or lack thereof, the use of and/or role of instrumentation, tempos, solos, vocals, etc. Section 3 Summarize your experience. -

Country Dance and Song and Society of America

I ,I , ) COUNTRY DANCE 1975 Number 7 Published by The Country Dance and Song AND Society of America EDITOR J. Michael Stimson SONG COUNTRY DANCE AND SONG is published annually. Subscription is by membership in the Society. Members also receive occasional newsletters. Annual dues are $8 . 00 . Libraries, Educational Organi zations, and Undergraduates, , $5.00. Please send inquiries to: Country Dance and Song Society, 55 Christopher Street, New York, NY 10014. We are always glad to receive articles for publication in this magazine dealing with the past, present or future of traditional dance and music in England and America, or on related topics . PHOTO CREDITS P. 5 w. Fisher Cassie P. 12 (bottom) Suzanne Szasz P. 26 William Garbus P. 27 William Garb us P. 28 William Garb us CONTENTS AN INTERVIEW WITH MAY GADD 4 TRADITION, CHANGE AND THE SOCIETY Genevieve Shimer ........... 9 SQUARE DANCING AT MARYLAND LINE Robert Dalsemer. 15 Copyright€>1975 by Country Dance Society, Inc. SONGFEST AND SLUGFEST: Traditional Ballads and American Revolutionary Propaganda Estelle B. Wade. 20 , CDSS REVISITS COLONIAL ERA • . • . • . • . • • . 26 TWO DANCES FROM THE REVOLUTIONARY ERA Researched by James Morrison ..................••. 29 CHEERILY AND MERRILLY: Our Music Director's Way with Singing Games and Children Joan Carr.............. 31 STAFF AND LEADERS'CONFERENCE Marshall Barron .•.......... 35 SALES James Morrison ............. 40 CDSS CENTERS .•......•.............•••.. 49 A: Well, they didn't have bands so much. Cecil Sharp was a mar velous piano player, AN INTERVIEW WITH and he had a wonder ful violinist, Elsie Avril, who played with him right from the be MAY GADD... ginning. We had just piano and violin in those days for all but the big theater This is the first part of an interview by Joseph Hickerson, performances. -

Adrian Belew Power Trio

This pdf was last updated: Dec/29/2010. Adrian Belew Power Trio King Crimson and Frank Zappa, David Bowie and Paul Simon, Talking Heads and Nine Inch Nails - Adrian Belew is well-known for his diverse travels around the musical map. Line-up Adrian Belew - guitar, vocals Julie Slick - bass Eric Slick - drums Andre Cholmondeley - tour manager/tech Plus one additional sound/tech manager On Stage: 3 Travel Party: 5 Website www.adrianbelew.net Biography Since 2006, Adrian Belew has led his favorite 'Power Trio' lineup, featuring Eric Slick on drums and Julie Slick on bass. They have been devastating audiences all around the USA and globally, from Italy to Canada to Germany to Japan. With the release of their brand- new CD 'Side Four - Live' they return to the road to stretch out the new material and introduce it to new audiences. The show will feature material from the new CD, classics from Adrian's many solo albums (including the recent 'Side One', 'SideTwo', and 'Side Three'), as well as solo moments, spirited improvisation and King Crimson compositions. 'Side One' features special guests Les Claypool of Primus and Danny Carey of Tool, and includes the Grammy-Nominated single - 'Beat Box Guitar'. The recently released 'Side Four (Live)' captures the current trio in a burning performance. Adrian is well-known for his diverse travels around the musical map - he first appeared on guitar-world radar when he joined Frank Zappa's band in 1977 for tours of the USA and Europe. When Frank Zappa hires you as his guitarist, people listen up. -

EMI Records Releases Li E at He EBC a Two-Disc Set of Radio Concerts

he rock-spectacle EMI Records r eleases Roll ing Stones tour, Tnamed after their Li e at he_ EBC a album Voodoo Lounge, two-disc set of radio combines a light show, concerts recorded by computer animation , video the Beatles in the blowups, and gigantic early '60s. "Free as inflatable props. Millions a Bird," an original watch the Stones prance unfinished track by through their classic and the late John Lennon, current hits like "love Is Strong." Voodoo lounge is finished, mixed becomes the highest with the live voices grossing tour in history with of Paul, George, and $115 million in ticket sales. Ringo, and included in the set. ominated for best femal e vocalist, Ncountry singer Mary of Santo Domingo de Ch apin Carpenter croons at Silos release their th e Country Music Awards CD , Chant. Heavy ceremony, but loses to Pam rotation on MTV Tillis. Carpenter's album turns the collection Stones in the Road tops the of ancient Gregorian country charts. chants into an un expected best-seller. he Canadian band Cowboy Junkies, Twhose big hit this year is "Sweet James," sings of isolation and despair on their latest album Pale Sun/Crescent Moon. I's a year of hits for ismissed as kiddie buu band, Gin artists, three 12-year I Blossoms. Their top Dold rappers who go by selling albu m New the name of Immature , get a Miserable Experience, new sound. Album Playtime covers "Hey Jealousy, " Is Over and hits "Never Lie" "Found Out About You ," and "Constanlly" pump them and "Until I Fall Away. -

Backstage Auctions, Inc. the Rock and Pop Fall 2020 Auction Reference Catalog

Backstage Auctions, Inc. The Rock and Pop Fall 2020 Auction Reference Catalog Lot # Lot Title Opening $ Artist 1 Artist 2 Type of Collectible 1001 Aerosmith 1989 'Pump' Album Sleeve Proof Signed to Manager Tim Collins $300.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1002 Aerosmith MTV Video Music Awards Band Signed Framed Color Photo $175.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1003 Aerosmith Brad Whitford Signed & Personalized Photo to Tim Collins $150.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1004 Aerosmith Joey Kramer Signed & Personalized Photo to Tim Collins $150.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Artist / Musician Signed Items 1005 Aerosmith 1993 'Living' MTV Video Music Award Moonman Award Presented to Tim Collins $4,500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1006 Aerosmith 1993 'Get A Grip' CRIA Diamond Award Issued to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1007 Aerosmith 1990 'Janie's Got A Gun' Framed Grammy Award Confirmation Presented to Collins Management $300.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1008 Aerosmith 1993 'Livin' On The Edge' Original Grammy Award Certificate Presented to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1009 Aerosmith 1994 'Crazy' Original Grammy Award Certificate Presented to Tim Collins $500.00 AEROSMITH - TIM COLLINS COLLECTION Awards, Plaques & Framed Items 1010 Aerosmith -

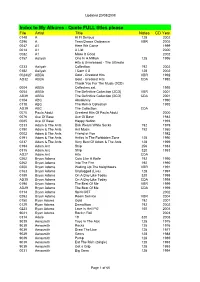

Album Backup List

Updated 20/08/2008 Index to My Albums - Quote FULL titles please File Artist Title Notes CD Year 0148 A Hi Fi Serious 128 2002 0296 A Teen Dance Ordinance VBR 2005 0047 A1 Here We Come 1999 0014 A1 A List 2000 0082 A1 Make It Good 2002 0157 Aaliyah One In A Million 128 1996 Hits & Unreleased - The Ultimate 0233 Aaliyah Collection 192 2002 0182 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 128 2002 0024/27 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits VBR 1992 AD32 ABBA Gold - Greatest Hits CDA 1992 Thank You For The Music (3CD) 0004 ABBA Collectors set 1995 0054 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) VBR 2001 AB39 ABBA The Definitive Collection (2CD) CDA 2001 0104 ABC Absolutely 1990 0118 ABC The Remix Collection 1993 AD39 ABC The Collection CDA 0070 Paula Abdul Greatest Hits Of Paula Abdul 2000 0076 Ace Of Base Ace Of Base 1983 0085 Ace Of Base Happy Nation 1993 0233 Adam & The Ants Dirk Wears White Socks 192 1979 0150 Adam & The Ants Ant Music 192 1980 0002 Adam & The Ants Friend or Foe 1982 0191 Adam & The Ants Antics In The Forbidden Zone 128 1990 0237 Adam & The Ants Very Best Of Adam & The Ants 128 1999 0194 Adam Ant Strip 256 1983 0315 Adam Ant Strip 320 1983 AD27 Adam Ant Hits CDA 0262 Bryan Adams Cuts Like A Knife 192 1990 0262 Bryan Adams Into The Fire 192 1990 0200 Bryan Adams Waking Up The Neighbours VBR 1991 0163 Bryan Adams Unplugged (Live) 128 1997 0189 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today 320 1998 AD30 Bryan Adams On A Day Like Today CDA 1998 0198 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me VBR 1999 AD29 Bryan Adams The Best Of Me CDA 1999 0114 Bryan Adams Spirit OST 2002 0293 Bryan Adams -

Ongratulations Hard -Rock Circles

the inaugural MTV European Music Awards show in Berlin in November 1994. After the Geffen years ended with the success of the "Big Ones" retrospective, Columbia was able to develop an aggressive international marketing strategy for its returning heroes, as Borchard recalls. "I worked closely with all the Columbia/Sony affiliates around the world," she says. "Our goal was to develop a fantastic launch and project -development plan to allow us to continue selling 'Nine Lives' steadily over the subsequent 12 to 18 months." With that goal in mind, the bandmembers undertook a series of "fan appreciation" events in Berlin, Paris, THE ACTION ABROAD Stockholm, London, Milan, Toronto and Tokyo, where Continued from page A -6 they hosted listening parties for groups of between 500 and 2,000 fans to be the first to hear "Nine Lives." RETURNING HEROES Another ambitious national and international tour was mounted to back the "Get A Grip" album in 1993 -94, with PUMPING UP DOWN UNDER Run D.M.C. rocked with Perry and Tyler in 1986. dates in Central and South America and an appearance at J Judging by the myriad week- doubt affected its sales. end pub bands playing Certainly, radio believes the Aerosmith covers or dressing band has the potential to raise like them, Aerosmith has a core its profile in this market. following Down Under, mostly in "They don't have much of a ongratulations hard -rock circles. Despite mini- heritage here," says Guy mal airplay, early records Dobson, program director at "Rocks" and "Toys In The Attic" Triple M in Sydney. -

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc Number Disc Count Track Number Track Count Year Date Mod ified Date Added Bit Rate Sample Rate Volume Adjustment Kind Equalizer Comments Plays Last Played Skips Last Ski ppedDancing MyQueen Rating ABBA LocationBenny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus/Stig Anderson ABBA For ever Gold I Rock 3715072 231 1 1 1 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBA Forever Gold I:0 1Knowing Dancing me, Queen.mp3 knowing you ABBA Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus/Stig Anderson ABBA Forever Gold I Rock 3885158 241 1 1 2 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBA Forever Gold I:0 2Take Knowing a chance me, knowingon me you.mp3 ABBA Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus ABBA Forever Gol d I Rock 3924028 244 1 1 3 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file 2 9/10/11 10:56 PM Audio:ABBA:ABBA ForeverMamma mia Gold I:03 ABBA Take a Bennychance Andersson/Björn on me.mp3 Ulvaeus/Stig Anderson ABBA For ever Gold I Rock 3428328 213 1 1 4 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file 2 9/10/11 10:59 PM Audio:ABBA:ABBA ForeverLay all Goldyour I:04love Mammaon me mia.mp3 ABBA Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus ABBA Forever Gol d I Rock 4401337 274 1 1 5 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBA Forever Gold I:0 5Super Lay alltrouper your love ABBA on me.mp3 Benny Andersson/Björn Ulvaeus ABBA Forever Gold I Rock 4081599 254 1 1 6 1998 10/9/08 3:03 PM 8/21/11 8:54 AM 128 44100 MPEG audio file Audio:ABBA:ABBAI -

The Backstreets Liner Notes

the backstreets liner notes BY ERIK FLANNIGAN AND CHRISTOPHER PHILLIPS eyond his insightful introductory note, Bruce Springsteen elected not to annotate the 66 songs 5. Bishop Danced RECORDING LOCATION: Max’s Kansas City, New included on Tracks. However, with the release York, NY of the box set, he did give an unprecedented RECORDING DATE: Listed as February 19, 1973, but Bnumber of interviews to publications like Billboard and MOJO there is some confusion about this date. Most assign the which revealed fascinating background details about these performance to August 30, 1972, the date given by the King songs, how he chose them, and why they were left off of Biscuit Flower Hour broadcast (see below), while a bootleg the albums in the first place. Over the last 19 years that this release of the complete Max’s set, including “Bishop Danced,” magazine has been published, the editors of Backstreets dated the show as March 7, 1973. Based on the known tour have attempted to catalog Springsteen’s recording and per- chronology and on comments Bruce made during the show, formance history from a fan’s perspective, albeit at times an the date of this performance is most likely January 31, 1973. obsessive one. This booklet takes a comprehensive look at HISTORY: One of two live cuts on Tracks, “Bishop Danced” all 66 songs on Tracks by presenting some of Springsteen’s was also aired on the inaugural King Biscuit Flower Hour and own comments about the material in context with each track’s reprised in the pre-show special to the 1988 Tunnel of Love researched history (correcting a few Tracks typos along the radio broadcast from Stockholm.