King Hu and Run Run Shaw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alternative Digital Movies As Malaysian National Cinema A

Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Hsin-ning Chang April 2017 © 2017 Hsin-ning Chang. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema by HSIN-NING CHANG has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Erin Schlumpf Visiting Assistant Professor of Film Studies Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT CHANG, HSIN-NING, Ph.D., April 2017, Interdisciplinary Arts Unfolding Time to Configure a Collective Entity: Alternative Digital Movies as Malaysian National Cinema Director of dissertation: Erin Schlumpf This dissertation argues that the alternative digital movies that emerged in the early 21st century Malaysia have become a part of the Malaysian national cinema. This group of movies includes independent feature-length films, documentaries, short and experimental films and videos. They closely engage with the unique conditions of Malaysia’s economic development, ethnic relationships, and cultural practices, which together comprise significant understandings of the nationhood of Malaysia. The analyses and discussions of the content and practices of these films allow us not only to recognize the economic, social, and historical circumstances of Malaysia, but we also find how these movies reread and rework the existed imagination of the nation, and then actively contribute in configuring the collective entity of Malaysia. 4 DEDICATION To parents, family, friends, and cats in my life 5 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor, Prof. -

Joseph Sunn Jue and Run Run Shaw out OF

CAAMFest 2014 Honors Two Film Production Pioneers: Joseph Sunn Jue and Run Run Shaw SAN FRANCISCO, Feb. 13, 2014 — The Center for Asian American Media (CAAM) is excited to showcase two pioneers from Asian and Asian American film history: Joseph Sunn Jue and Run Run Shaw. Legendary Chinese American producer Joseph Sunn Jue formed the Grandview Film Company in San Francisco in 1933. It was the only operating Chinese American motion picture company in the United States during the 1930s. With the help of the Hong Kong Film Archive, CAAMFest 2014 will present two of seven surviving Grandview productions for the first time in 67 years. Run Run Shaw is one of the most influential figures in the Asian entertainment industry. The Hong Kong mogul and movie producer was also a philanthropist who donated billions to charities in his lifetime and also founded Shaw Brothers Studios. On January 7, 2014, Shaw passed away at the age of 106. CAAM pays tribute to his legacy with a screening of three of his studio’s spectacular cinematic creations. CAAM is pleased to present these films at the Great Star Theater, Chinatown’s last remaining film theater which showed the early works of Run Run Shaw. OUT OF THE VAULTS: REDISCOVERING GRANDVIEW FILMS CAAMFest’s Out of the Vaults showcases films ripe for rediscovery. This year’s presentation highlights Joseph Sunn Jue and his Grandview Film Company. Producing a series of imaginative comedies, melodramas and romances geared towards the Cantonese‐speaking market in the 1930s, Grandview captured a unique era in the lives of Chinese Americans. -

Narrative Space in the Cinema of King Hu 127

interstate laws directed against the telegraph, the telephone, and the railway, see Questions of Chinese Aesthetics: Film Form and Ferguson and McHenry, American Federal Government, 364, and Harrison, "'Weak- ened Spring,'" 70. Narrative Space in the Cinema of King Hu 127. Mosse, Nationalism and Sexuality. by Hector Rodnguez 128. Goldberg, Racist Culture. Much of the concern over the Johnson fight films was directed at the effects they would have on race relations (e.g., the possibility of black people becoming filled with "race pride" at the sight ofjohnson's victories). This imperialistic notion of reform effectively positioned black audiences as need- In memory of King Hu (1931-1997) ing moral direction. 129. Orrin Cocks, "Motion Pictures," Studies in Social Christianity (March 1916): 34. The concept of Chinese aesthetics, when carefully defined and circumscribed, illu- minates the relationship between narrative space and cultural tradition in the films of King Hu. Chinese aesthetics is largely based on three ethical concerns that muy be termed nonattachment, antirationalism, and perspectivism. This essay addresses the representation of "Chineseness" in the films of King Hu, a director based in Hong Kong and Taiwan whose cinema draws on themes and norms derived from Chinese painting, theater, and literature. Critical discussions of his work have often addressed the question of the ability of the cinema, a for- eign medium rooted in a mechanical age, to express the salient traits of Chinas longstanding artistic traditions. At stake is the relationship between film form and the national culture, embodied in the concept of a Chinese aesthetic. Film scholars tend to define the main features of Chinese aesthetics selec- lively, emphasizing a few stylistic norms out of a broad repertoire of available his- tones and traditions, and the main criterion for this selection is the sharp difference between those norms and the presumed realism of European art before modern- ism. -

Newsletter 34

Hong Kong Film Archive Quarterly 34 Newsletter 11.2005 Chor Yuen: A Lifetime in the Film Studio Three Glimpses of Takarada Akira Mirage Yellow Willow in the Frost 17 Editorial@ChatRoom English edition of Monographs of HK Film Veterans (3): Chor Yuen is to be released in April 2006. www.filmarchive.gov.hk Hong Kong Film Archive Head Angela Tong Section Heads Venue Mgt Rebecca Lam Takarada Akira danced his way in October. In November, Anna May Wong and Jean Cocteau make their entrance. IT Systems Lawrence Hui And comes January, films ranging from Cheung Wood-yau to Stephen Chow will be revisited in a retrospective on Acquisition Mable Ho Chor Yuen. Conservation Edward Tse Reviewing Chor Yuen’s films in recent months, certain scenes struck me as being uncannily familiar. I realised I Resource Centre Chau Yu-ching must have seen the film as a child though I couldn’t have known then that the director was Chor Yuen. But Research Wong Ain-ling coming to think of it, he did leave his mark on silver screen and TV alike for half a century. Tracing his work brings Editorial Kwok Ching-ling Programming Sam Ho to light how Cantonese and Mandarin cinema evolved into Hong Kong cinema. Today, in the light of the Chinese Winnie Fu film market and the need for Hong Kong cinema to reorient itself, his story about flowers sprouting from the borrowed seeds of Cantonese opera takes on special meaning. Newsletter I saw Anna May Wong for the first time during the test screening. The young artist was heart-rendering. -

Annual Report 2002-2003 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with Limited Liability)

2002-2003 Annual Report (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) 年報 2002-2003 年報 Annual Report 2002-2003 Panorama International Holdings Limited PanoramaAnnual Report 2002-2003 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE GROWTH ENTERPRISE MARKET (“GEM”) OF THE STOCK EXCHANGE OF HONG KONG LIMITED (THE “STOCK EXCHANGE”). GEM has been established as a market designed to accommodate companies to which a high investment risk may be attached. In particular, companies may list on GEM with neither a track record of profitability nor any obligation to forecast future profitability. Furthermore, there may be risks arising out of the emerging nature of companies listed on GEM and the business sectors or countries in which the companies operate. Prospective investors should be aware of the potential risks of investing in such companies and should make the decision to invest only after due and careful consideration. The greater risk profile and other characteristics of GEM mean that it is a market more suited to professional and other sophisticated investors. Given the emerging nature of companies listed on GEM, there is a risk that securities traded on GEM may be more susceptible to high market volatility than securities traded on the Main Board of the Stock Exchange and no assurance is given that there will be a liquid market in the securities traded on GEM. The principal means of information dissemination on GEM is publication on the Internet website operated by the Stock Exchange. Listed companies are not generally required to issue paid announcements in gazetted newspapers. Accordingly, prospective investors should note that they need to have access to the GEM website in order to obtain up-to-date information on GEM- listed issuers. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY An Jingfu (1994) The Pain of a Half Taoist: Taoist Principles, Chinese Landscape Painting, and King of the Children . In Linda C. Ehrlich and David Desser (eds.). Cinematic Landscapes: Observations on the Visual Arts and Cinema of China and Japan . Austin: University of Texas Press, 117–25. Anderson, Marston (1990) The Limits of Realism: Chinese Fiction in the Revolutionary Period . Berkeley: University of California Press. Anon (1937) “Yueyu pian zhengming yundong” [“Jyutpin zingming wandung” or Cantonese fi lm rectifi cation movement]. Lingxing [ Ling Sing ] 7, no. 15 (June 27, 1937): no page. Appelo, Tim (2014) ‘Wong Kar Wai Says His 108-Minute “The Grandmaster” Is Not “A Watered-Down Version”’, The Hollywood Reporter (6 January), http:// www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/wong-kar-wai-says-his-668633 . Aristotle (1996) Poetics , trans. Malcolm Heath (London: Penguin Books). Arroyo, José (2000) Introduction by José Arroyo (ed.) Action/Spectacle: A Sight and Sound Reader (London: BFI Publishing), vii-xv. Astruc, Alexandre (2009) ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Caméra-Stylo ’ in Peter Graham with Ginette Vincendeau (eds.) The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks (London: BFI and Palgrave Macmillan), 31–7. Bao, Weihong (2015) Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915–1945 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press). Barthes, Roland (1968a) Elements of Semiology (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1968b) Writing Degree Zero (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1972) Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers), New York: Hill and Wang. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 203 G. -

Episode 289 – Talking Sammo Hung | Whistlekickmartialartsradio.Com

Episode 289 – Talking Sammo Hung | whistlekickMartialArtsRadio.com Jeremy Lesniak: Hey there, thanks for tuning in. Welcome, this is whistlekick martial arts radio and today were going to talk all about the man that I believe is the most underrated martial arts actor of today, possibly of all time, Sammo Hung. If you're new to the show you may not know my voice I'm Jeremy Lesniak, I'm the founder of whistlekick we make apparel and sparring gear and training aids and we produce things like this show. I wanna thank you for stopping by, if you want to check out the show notes for this or any of the other episodes we've done, you can find those over at whistlekickmartialartsradio.com. You find our products at whistlekick.com or on Amazon or maybe if you're one of the lucky ones, at your martial arts school because we do offer wholesale accounts. Thank you to everyone who has supported us through purchases and even if you aren’t wearing a whistlekick shirt or something like that right now, thank you for taking the time out of your day to listen to this episode. As I said, here on today's episode, were talking about one of the most respected martial arts actor still working today, a man who has been active in the film industry for almost 60 years. None other the Sammo Hung. Also known as Hung Kam Bow i'll admit my pronunciation is not always the best I'm doing what I can. Hung originates from Hong Kong where he is known not only as an actor but also as an action choreographer, producer, and director. -

PDF Full Report

Heightening Sense of Crises over Press Freedom in Hong Kong: Advancing “Shrinkage” 20 Years after Returning to China April 2018 YAMADA Ken-ichi NHK Broadcasting Culture Research Institute Media Research & Studies _____________________________ *This article is based on the same authors’ article Hong Kong no “Hodo no Jiyu” ni Takamaru Kikikan ~Chugoku Henkan kara 20nen de Susumu “Ishuku”~, originally published in the December 2017 issue of “Hoso Kenkyu to Chosa [The NHK Monthly Report on Broadcast Research]”. Full text in Japanese may be accessed at http://www.nhk.or.jp/bunken/research/oversea/pdf/20171201_7.pdf 1 Introduction Twenty years have passed since Hong Kong was returned to China from British rule. At the time of the 1997 reversion, there were concerns that Hong Kong, which has a laissez-faire market economy, would lose its economic vigor once the territory is put under the Chinese Communist Party’s one-party rule. But the Hong Kong economy has achieved generally steady growth while forming closer ties with the mainland. However, new concerns are rising that the “One Country, Two Systems” principle that guarantees Hong Kong a different social system from that of China is wavering and press freedom, which does not exist in the mainland and has been one of the attractions of Hong Kong, is shrinking. On the rankings of press freedom compiled by the international journalists’ group Reporters Without Borders, Hong Kong fell to 73rd place in 2017 from 18th in 2002.1 This article looks at how press freedom has been affected by a series of cases in the Hong Kong media that occurred during these two decades, in line with findings from the author’s weeklong field trip in mid-September 2017. -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

Report of the Directors

REPORT OF THE DIRECTORS The Directors have pleasure in presenting their report together with the audited financial statements for the year ended 31st March 2006. GENERAL INFORMATION, PRINCIPAL ACTIVITIES AND GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS OF OPERATIONS The Company is a limited company incorporated and publicly listed in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (“Hong Kong”). The address of the registered office is Lot 220 Clear Water Bay Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong. The financial statements are presented in Hong Kong dollars which are the same as the functional currency of the Company. The principal activities of the Company during the year are investment holding and investments in the media and entertainment industries. The activities and particulars of the subsidiaries and associated companies are shown in Note 11 and 12 to the financial statements respectively. The analysis of the Group’s performance for the year by business and geographical segments is set out in Note 2 to the financial statements. RESULTS The results of the Group for the year ended 31st March 2006 are set out in the consolidated income statement on page 28. DIVIDENDS The Directors have declared an interim dividend of HK$0.06 per ordinary share, totalling HK$23,903,424 which was paid on 26th January 2006. The Directors recommend the payment of a final dividend of HK$0.34 per ordinary share, totalling HK$0.40, in respect of the year ended 31st March 2006 payable to shareholders whose names appear on the Register of Members of the Company on 6th September 2006. Final dividend, if approved, will be paid to shareholders on 26th October 2006. -

2016 Annual Report

FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS Revenue and Prot Attributable to 2016 2015 Change Equity Holders of the Company Revenue (Continuing operations) Prot Attributable to Equity Holders of the Company Performance 6,000 Earnings per share HK$1.14 HK$3.04 -62% Dividends per share 5,000 - Interim HK$0.60 HK$0.60 – - Final – HK$2.00 -100% 4,000 HK$0.60 HK$2.60 -77% 3,000 HK$’mil HK$’mil HK$’ million HK$’ Revenue 2,000 - Hong Kong TV broadcasting 2,707 3,105 -13% - Hong Kong digital new media 1,000 business 230 170 35% - Programme licensing and 0 distribution 1,019 951 7% 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 - Overseas pay TV operations 169 186 -9% YEAR - Channel operations 90 105 -14% Earnings & Dividends# Per Share - Other activities 191 129 48% - Inter-segment elimination (196) (191) 2% Earnings per Share Dividends# per Share 4,210 4,455 -5% 4.5 HK$’mil HK$’mil 4 Segment (loss)/profit* 3.5 - Hong Kong TV broadcasting (71) 551 N/A 3 - Hong Kong digital new media business (29) 41 N/A 2.5 - Programme licensing and HK$ 2 distribution 444 410 8% - Overseas pay TV operations (40) (30) 31% 1.5 - Channel operations 2 18 -87% 1 - Other activities 27 11 151% 0.5 - Corporate support (33) – N/A - Inter-segment elimination 1 (1) N/A 0 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 301 1,000 -70% YEAR # excluding special dividend Total expenses∆ 3,888 3,439 13% 2016 Revenue by Operating Segment Profit attributable to equity holders 500 1,331 -62% % relating to 2015 are shown in brackets 31 December 31 December Hong Kong TV 2016 2015 broadcasting HK$’mil HK$’mil 63% (69%) Total assets 12,357 9,113 36% -

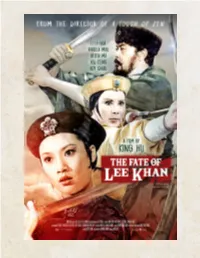

The-Fate-Of-Lee-Khan Presskit.Pdf

presents NEW 2K DIGITAL RESTORATION Hong Kong & Taiwan / 1973 / Action / Mandarin with English Subtitles 106 minutes / 2.35:1 / 5.1 Surround Sound U.S. THEATRICAL PREMIERE Opening April 5th in New York at Metrograph Press Contacts: Michael Krause | Foundry Communications | (212) 586-7967 | [email protected] Michael Lieberman | Metrograph | (212) 660-0312 | [email protected] Film Movement Booking Contacts: Clemence Taillandier | Theatrical | (201) 736-0261 | [email protected] Maxwell Wolkin | Festivals & Non-Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x211 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS In his follow-up to the critically acclaimed A TOUCH OF ZEN, trailblazing filmmaker King Hu brings together an all-star female cast, including Hong Kong cinema stalwart Li Li-hua and Angela “Lady Kung Fu” Mao, in this lively martial arts adventure. When Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army, resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. Featuring stunning action sequences choreographed by Jackie Chan’s “Kung Fu elder brother” Sammo Hung and a generous mix of intrigue and humor, THE FATE OF LEE KHAN is a legendary wuxia masterpiece. SHORT SYNOPSIS Lee Khan, a powerful general of the oppressive Yuan Dynasty, procures the battle map of the Chinese rebel army. Resistance fighters, aided by an undercover girl-gang, strive to corner him at an inn. LOGLINE King Hu's legendary wuxia masterpiece, starring Li Li-hua, Angela Mao and Hsu Feng. SELECT PRESS “The Fate of Lee Khan is to the Chinese martial arts movie what Once Upon a Time in the West is to the Italian Western: a brilliant anthology of its genre's theme and styles, yielding an exhilaratingly original vision.” –Time Out “The Fate of Lee Khan is a masterclass in getting the maximum from every aspect of production.