Draft Restoration Plan and Environmental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Times on Buzzard's Bay

mw fa noll mJI BRIGHT LEGACY ODe half tile IDCOlDe froID tb1I Leaaer. "b1eh .... re ee1..ed 10 .810 oDder tile "W of JONATHAN BIlOWN BIlIGHT of WoItIwo. M_hoa.tu.1oto be ellpeDd.d for bookl for tile CoU. Library. The otller half of til. IDcolDe :e:::t::d~=h.r 10 H....... UDI...nltyfortll. HINIlY BIlIGHT. JIl•• "ho cIIed at Waterto..... MaaadI_.10'686. 10 til. aboeDCD of loch deoceodootl. otller penoD' oro eUpbl. to til. ocbolanhlpo. Th.,,1U reqolreo tIIat t1110 100000_ lDeDt Ihall be ...... 10 ...ery book "ded to tile Library ....r Ito ,rorioIooo. .... ogle R FROM THE- BRIGHT LEGACY. Descendants of Henry Brifl'hl, jr., who died at Water. town,MasS., in J6S6,are entitled to hold scholarships in Harvard College, established in ,830 under the wil,-of JONATHAN BROWN BRIGHT of Waltham, Mass., with one half the income of this l.egacy. ~uch descendants failing, other persons are eligible to the scholarships. The will requires that this a.I)nOUDcement shall be made in every book added'" to the Library under its provisions. Received £ j Coogle COLONIAL TIMES ON BUZZARD'S BAY BY WILLIAM ROOT BLISS ..ThIs Is the place. Stand still, my steed, Let me review the scene, And summon from the shadowy Put The (ClI1IllI lhat once haye been.It LoKGnLLOW. / ,'BOSTON AND NEW YORK HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY _fie flitl~ibe tl'rr-" ftam~ 1888 Dig; Ized by Google Copyright, .888, By WILLIAM ROOT BLISS. Tlu RirJlf',iu P...... Ca..u..itl,p: Electrotyped and Printed by H. O. Houghton 8: Co. -

Mapping & Data Requests Fulfilled by BBNEP's Regional Planner

Mapping & Data Requests Fulfilled by BBNEP's Regional Planner - FY15 (July 1, 2014 - June 30, 2018) Date Person/Organization Making Request Description of Request 7-1-14 Mark Rasmussen - Buzzards Bay Coalition Aerial map of Elizabeth Islands showing natural resources 7-7-14 Craig Mercier - U.S. Coast Guard Edits to 2 Buzzards Bay Nautical Charts Topo map of Nasketucket Fields CR (Fairhaven CR#14) and send shapefile to 7-10-14 Allen Decker - Buzzards Bay Coalition MassGIS 7-14-14 Allen Decker - Buzzards Bay Coalition Edits to Nasketucket Fields CR map 2 maps (aerial and parcel) of Tinkham property in Mattapoisett showing proposed 7-15-14 Allen Decker - Buzzards Bay Coalition subdivision 7-15-14 Allen Decker - Buzzards Bay Coalition Edits to Shaw's Cove maps 7-15-14 Allen Decker - Buzzards Bay Coalition Create map of Shaw's Cove Improvement Association property in Fairhaven 7-15-14 Brendan Annett - Buzzards Bay Coalition Update Nasketucket Bay Status map 7-18-14 Brendan Annett - Buzzards Bay Coalition Create a Size E Nasketucket Bay Status map 7-18-14 Steve Sloan - Buzzards Bay Coalition Standard property map of Lewis property in Westport 7-18-14 Yelena Sheynin - Sippican Lands Trust 2 size E aerials of Howland Marsh and Osprey Marsh properties 7-18-14 Yelena Sheynin - Sippican Lands Trust Edits to Marion Open Space map 7-21-14 Allen Decker - Buzzards Bay Coalition Edits to Tinkham map - Mattapoisett Two topo maps and land use calculations for 2 state CR applications (DeNormandie 7-21-14 Allen Decker - Buzzards Bay Coalition Farm West & -

JYC 2011 Annual Cruise

Jamestown Yacht Club 2011Annual Cruise Guide Hello and welcome to the 2011 Jamestown Yacht Club annual cruise. We expect a wonderful trip into Buzzards Bay, through the Cape Cod Canal, and onto Provincetown, Massachusetts. This document is your reference for the cruise. The goal is to provide information and structure, but you can of course set your own schedule. Our motto this year is "TideTide waits for no man!man!!!!!". It was planned so we could have favorable current through the canal. A special thanks to Vic Calabretta for his help on this critical part. Our fleet consists of 10 boats and 23 sailors. Everybody is welcome and everybody is included. Its likely that not all will want to do the same thing at the same time. We will have several happy hours and are planning two events in Provincetown. One is a whale watch tour and the other is a scavenger hunt. We traditionally have one night out for a nice dinner. We encourage everyone to participate, but respect if you want to go off on your own. If you have any questions please email me at [email protected] . While underway I will be monitoring Channel 16 and on the top of each hour we will broadcast on Channel 72. We look forward to sailing with you and very happy that you are part of this great adventure. Edward Doherty Sailing Vessel "Patriot" JYC Cruising Chair Boat Name Manuf. Length Sail # Crew Crew Katie C Island 35 88 Vic Judy Packet Blackbird Corsair 28 71 Nick Sue High Spirits Bristol 35.5 none Steve Rita BonVivant Valiant Mike Marilyn Gavin Magic Roundabout Jeanneau 35 41Y-2 Winston Judy Patriot Beneteau 36 78 Ed Melanie James Madeline Pooka Catalina 36 1339 John Joe Mio Sogno Jeanneau 36 Tony Carol Seyanna II Person 31 38 Bruce Hazel Voyager Tashiba 40 60262 Clifford Susan Please fly your JYC Burgee while at anchor or on a mooring. -

NAVIGATION WORKBOOK 1210 Tr

NAVIGATION WORKBOOK 1210 Tr DAVID BURCH LARRY BRANDT www.starpathpublications.com Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ v Scope ............................................................................................................................... v Chart 1210 Tr ................................................................................................................. v Terminology .................................................................................................................... v Magnetic Variation ......................................................................................................... v Tides and Currents ......................................................................................................... v Tools of the Trade .......................................................................................................... vi For more Help ............................................................................................................... vi EXERCISES .................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1 – THE ROLE OF NAVIGATION ................................................................1 CHAPTER 2 – NAUTICAL CHARTS AND CHART READING .................................... 3 CHAPTER 3 – OTHER NAVIGATION AIDS ................................................................ 6 CHAPTER 4 – COMPASS USE ..................................................................................... -

2018 Annual Report Accomplishments Save Buzzards Bay

2018 ANNUAL REPORT ACCOMPLISHMENTS SAVE BUZZARDS BAY. You’ve undoubtedly seen our blue-and-white bumper stickers FROM THE on cars, boats, and tackle boxes around the region and on a big banner down the side PRESIDENT of our downtown New Bedford headquarters. But what does it really mean beyond being a catchy slogan? AND CHAIR Saving Buzzards Bay requires a tireless dedication to our mission, an intense focus on the issues that matter most, and big goals that may seem impossible until they’re done. It’s accomplished through ambitious and forward-thinking projects like the ones outlined in this report, which we’re proud to share with you, our members and supporters. These are your wins. In a world where it’s often difficult In a world where it’s to see the impact of our daily actions, your often difficult to see the support for the Buzzards Bay Coalition is impact of our daily yielding tangible benefits for our quality of actions, your support for life and for the environmental health of our the Buzzards Bay Coalition own backyards. is yielding tangible benefits for our quality 2018 was a year of progress on many of the of life and for the projects that will shape the future of our environmental health of local environment. On the water, the largest our own backyards. multi-town pollution reduction project in the Bay’s history moved into the next phase of action, which will ultimately connect more upper Bay homes to world-class wastewater treatment (p. 3). We’re also continuing to lead the way to demonstrate solutions to nitrogen pollution from septic systems in communities across the region (p. -

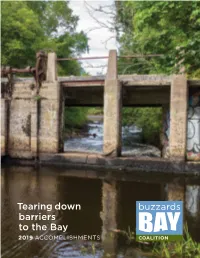

2019 Annual Report

Tearing down barriers to the Bay 2019 ACCOMPLISHMENTS FROM THE Tearing down PRESIDENT AND CHAIR barriers to the Bay SOMETHING HAPPENED ON THE WEWEANTIC RIVER THIS YEAR that hasn’t happened in centuries: the river and the tide and all of the fish within them began flowing freely into the Bay. The change occurred with the removal of a dam at the Coalition’s Horseshoe Mill property in West Wareham. The dam’s eradication is the realization of our work to restore natural passageways and wetlands habitat at the site for fish and aquatic plants. It also will open more of the river to kayaking and canoeing, fishing and walking, and more. Much work remains to be done at the site, and there are many more harmful dams along the Bay, but the dam’s removal marked a critical milestone in improving the health of our watershed. In 2019, we made significant progress in removing other barriers to improving and protecting our beautiful Buzzards Bay and watershed. In some cases, the obstacles have been physical and visible, as was the case at Horseshoe Mill; often, the hurdles consist of policies and practices that result in pollution and neglect, or in socioeconomic barriers that keep many people from using and enjoying our region’s greatest natural resource. On the water, our longtime efforts to address two of the Bay’s largest sources of nitrogen pollution—the wastewater treatment plants in Fairhaven and Marion—resulted in agreements in each town to correct the problems at the facilities (p. 2). We also launched a new effort to help the Bay’s salt marshes adapt to climate change (p. -

Cuttyhunk Forever 2020 ACCOMPLISHMENTS from the PRESIDENT and CHAIR (And a Few of the Kids That Inspire Us)

Cuttyhunk Forever 2020 ACCOMPLISHMENTS FROM THE PRESIDENT AND CHAIR (and a few of the kids that inspire us) Looking out from the hills that crown Cuttyhunk, you see dynamic beaches and coastal grasslands bordered by brilliant, blue waters in every direction. The wash of the tide and the call of birds blend with the breeze in a peaceful and soothing harmony. It is a magical place. To visit Cuttyhunk is to fall in love with Buzzards Bay. The Coalition has long sought to protect the island—for habitat, for clean water, and for its unique power to inspire people to protect the Bay. This year, thanks to the generosity and commitment of so many, we placed 68 acres of land under permanent protection, the first phase in preserving the remaining undeveloped property on the island. The protection of Cuttyhunk is the realization of a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. We seek to capitalize on every opening to better protect the Bay, and in 2020, we made significant progress, despite the challenges presented by the pandemic that has impacted us all. On the water, we reached a major milestone in our efforts to address the largest source of nitrogen pollution to our Bay—septic systems. In West Falmouth, we completed a multi- year effort to install 30 nitrogen-reducing septic systems, demonstrating the effectiveness of these systems in limiting pollution to the Bay (p. 6). We also began work in Fairhaven and Dartmouth testing a method to halt the decline of salt marshes, which are critical for habitat, clean water, and protection against storms and sea-level rise (p. -

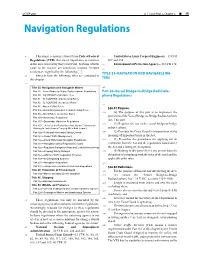

Navigation Regulations

26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 2 ¢ 35 Navigation Regulations (1) This chapter contains extracts from Code of Federal (7) United States Army Corps of Engineers—33 CFR Regulations (CFR) that are of importance to mariners 207 and 334 in the area covered by this Coast Pilot. Sections of little (8) Environmental Protection Agency—40 CFR 140 value to the mariner are sometimes omitted. Omitted (9) sections are signified by the following [...] TITLE 33–NAVIGATION AND NAVIGABLE WA- (2) Extracts from the following titles are contained in TERS this chapter. (3) Title 33: Navigation and Navigable Waters (10) Part 26—Vessel Bridge-to-Bridge Radiotelephone Regulations Part 26–Vessel Bridge-to-Bridge Radiotele- Part 80—COLREGS Demarcation Lines phone Regulations Part 81—72 COLREGS: Implementing Rules Part 82—72 COLREGS: Interpretive Rules (11) Part 88—Annex V: Pilot Rules §26.01 Purpose. Part 89—Inland Navigation Rules: Implementing Rules (12) (a) The purpose of this part is to implement the Part 90—Inland Rules: Interpretive Rules provisions of the Vessel Bridge-to-Bridge Radiotelephone Part 110—Anchorage Regulations Act. This part– Part 117—Drawbridge Operation Regulations (13) (1) Requires the use of the vessel bridge-to-bridge Part 157—Rules for the Protection of the Marine Environment Relating to Tank Vessels Carrying Oil in Bulk (in part) radiotelephone; Part 160—Ports and Waterways Safety-General (14) (2) Provides the Coast Guard’s interpretation of the Part 161—Vessel Traffic Management meaning of important terms in the Act; Part 162—Inland Waterways Navigation Regulations (15) (3) Prescribes the procedures for applying for an Part 164—Navigation Safety Regulations (in part) exemption from the Act and the regulations issued under Part 165—Regulated Navigation Areas and Limited Access Areas the Act and a listing of exemptions. -

Buzzards Bay Coalition's 2017 Annual Report

2017 ANNUAL REPORT ACCOMPLISHMENTS EACH YEAR, WE STRUGGLE WITH THE JOYFUL TASK OF BOILING DOWN A FROM THE year of accomplishments to share with you – our members and supporters – into PRESIDENT far too few printed pages. Because of your strong commitment and support, the Buzzards Bay Coalition’s AND CHAIR unique blend of science-based advocacy, ambitious land conservation, and broad community engagement continued to make a profound impact on the lives of everyone who are fortunate to call this region home. This year saw landmark land conservation deals closed and inspiring new doors opened. Ocean View (page 14), Carvalho Farm (page 3), and the 164 acres of wellhead forest we protected in the Mattapoisett River Valley (page 4) are all vital to the future of our Bay and region. The Coalition is becoming more effective every year in saving these irreplaceable parts of the Bay landscape. To reduce pollution, we remain laser-focused on tackling the greatest threat facing the Bay – nitrogen – and using every science, advocacy, and legal tool available to cleanup old sources and arrest new ones. Perhaps most exciting is the work we are doing on-the-ground with homeowners to install dozens of advanced nitrogen-reducing septic systems – expanding from our pilot efforts in West Falmouth to communities from Westport to Tisbury – to change the way we treat residential wastewater forever (pages 7-9). And in the Upper Bay, where children and families lack affordable access to the wonders of our local environment, we made history when Governor Baker approved our plans to create the Onset Bay Center as a hub of on-the-water exploration (page 11). -

2020 Bay Current

VOL. 31 CURRENT FALL 2020 NEWS FROM THE BUZZARDS BAY COALITION Great things are happening all around the Bay, thanks to you. Inside Read how your support: Reduces nitrogen pollution PAGE 2 Preserves Cuttyhunk Island from development PAGE 4 Restores rivers and streams PAGE 5 Connects people with the Bay’s wonders PAGES 6-7 SCIENCE & ADVOCACY The success of the nitrogen-reducing septic systems installed around West Falmouth Harbor is inspiring Project significantly reduces more property owners to take action. nitrogen pollution to West Falmouth Harbor Coalition finishes four-year effort to install nitrogen-reducing septic systems on 30 West Falmouth properties The 30 nitrogen-reducing septic systems that the Coalition helped install on properties surrounding West Falmouth Harbor are making a difference for clean water. Initial monitoring shows that the systems collectively remove 70 percent of the nitrogen that previously would have flowed into the harbor. In high concentrations, nitrogen clouds bay waters, fuels algae growth, and kills underwater eelgrass beds and fish and shellfish populations. And the problem, intensified by climate change, has been particularly acute in West Falmouth Harbor. Septic systems are the largest source of nitrogen pollution across all of Buzzards Bay. To address the problem, the Coalition organized an effort to install nitrogen-reducing septic systems, partnering with town, county, state and federal agencies, as well as local property owners. The four-year effort installed systems on properties with a variety of different uses, including seasonal and year-round homes, a tennis club, a neighborhood fire station, and a nonprofit educational institution. Much more remains to be done to restore West Falmouth Harbor water quality. -

31Edbb D2fl5 Nse E

UMASS/AMHERST 31EDbb D2fl5 nSE E ^/ illy 'i'i^';*H I I S \: H-^ COM PLIM EINTS OF WILLIAM S. McNARY, Chairman, CHARLES C. PAINE, GEORGE M. HARLOW, State House, BOSTON. FREDERICK N. WALES, Clerk of Board. Public Document No. 11 THIETY-SEVENTH ANNUAL EEPOET BOARD OF HARBOR AND LAND COMMISSIONERS. For the Year 1915. BOSTON: WEIGHT & POTTEE FEINTING CO., STATE PEINTEES, 32 DEENE STEEET. 1916. Approved bt The State Boaed op Publication. ©fje <!lommona)eaItl) of iIlas0Ocl)U0ett0. REPORT. To the Honorable the Senate and House of Representatives of the Common- wealth of Massachusetts. The Board of Harbor and Land Commissioners, pursuant to the provisions of law, respectfully submits its annual report for the year 1915, covering a period of twelve months, from Nov. 30, 1914, being the thirty-seventh annual report of the Board since its establishment by chapter 263 of the Acts of 1879. The present organization of the Board is as follows: William S. McNary of Boston, chairman, Charles C. Paine of Barn- stable, George M. Harlow of Boston. From Dec. 1, 1914, to Nov. 30, 1915, the Board has given 266 formal and informal hearings, and has received 182 peti- tions for the improvement and protection of rivers, harbors and foreshores, for licenses to build and maintain structures, for privileges in tidewaters. Great Ponds, Connecticut River and Merrimac River, to dredge material, to remove material from beaches and for other purposes. Ninety-five licenses for structures and privileges in tidewaters. Great Ponds, Connecticut River and Merrimac River have been granted during the year; also 68 permits for dredging, the removal of material from beaches and for other purposes. -

Vineyard Sound and Buzzards Bay

210 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 5 26 SEP 2021 Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 2—Chapter 5 70°30'W NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 71°W 42°N MASSACHUSETTS CAPE COD CANAL 13230 Onset Marion Mattapoisett 13236 New Bedford TS BUZZARDS BAY 13229 AND Falmouth CHUSET 13235 13232 Woods Hole MASSA RHODE ISL RHODE 41°30'N Naushon Island VINEYARD SOUND Vineyard Haven Pasque Island 13228 Nashawena Island Cuttyhunk Island 13229 Edgartown Mar tha’s V ineyard Gay Head 13238 Nomans Island 13233 RHODE ISLAND SOUND 13237 13218 41°N 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 2, Chapter 5 ¢ 211 Vineyard Sound and Buzzards Bay (1) This chapter describes Vineyard Sound and Buzzards or leaving Vineyard Sound should stay at least 3.5 miles Bay following the Massachusetts coast of Vineyard southward of the southwest end of Cuttyhunk Island. Sound, the northwestern shore of Martha’s Vineyard, the (10) eastern shore of Buzzards Bay, the Cape Cod Canal and Anchorages the western shore of Buzzards Bay. Also described are (11) Woods Hole is the only anchorage providing shelter Woods Hole, Cuttyhunk, Onset, Wareham and the port from all winds for vessels drawing more than 10 feet. In of New Bedford, as well as the numerous fishing and northerly and westerly winds, good anchorage may be yachting centers along the sound and bay. had in Tarpaulin Cove. In southerly winds, shelter can (2) be had in Menemsha Bight, although Vineyard Haven COLREGS Demarcation Lines is generally used.