Arbeitsberichte 59 BRILLIANT INNES CUTHILL Innes Has Been Professor of Behavioural Ecology at the University of Bristol Since

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Reproductive PATTERNS and Human-INFLUENCED Z]`Ynagj Af Zjgof Z]Yjk& Aehda[Ylagfk ^Gj the Conservation of LARGE Carnivores](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6785/reproductive-patterns-and-human-influenced-z-ynagj-af-zjgof-z-yjk-aehda-ylagfk-gj-the-conservation-of-large-carnivores-436785.webp)

Reproductive PATTERNS and Human-INFLUENCED Z]`Ynagj Af Zjgof Z]Yjk& Aehda[Ylagfk ^Gj the Conservation of LARGE Carnivores

P Natural and Department Ecology of Resource Management Fgjo]_aYfMfan]jkalqg^Da^]K[a]f[]kMfan]jkal]l]l^gjeadb¬ hilosophiae Doctor <]hYjlYe]flg\]:ag\an]jka\Y\q?]klaf9eZa]flYd& Universidad de León E-24071 León, Spain. www.unileon.es Reproductive patterns and human-influenced ( P Z]`YnagjafZjgofZ]Yjk&Aehda[Ylagfk^gj h D) the conservation of large carnivores. Thesis 2010:01 Thesis J]hjg\mckbgfke¬fkl]jg_e]ff]kc]kcYhlYl^]j\k]f\jaf_`gkZjmfZb¬jf& Cgfk]cn]fk]j^gjZ]nYjaf_]fYnklgj]jgn\qj& Andrés Ordiz %g_Zagnal]fkcYh Reproductive patterns and human-influenced behavior in brown bears Implications for the conservation of large carnivores Reproduksjonsmønster og menneskeskapt atferdsendring hos brunbjørn Konsekvenser for bevaringen av store rovdyr Philosophiae Doctor (PhD) Thesis Andrés Ordiz Dept. of Ecology and Natural Resource Management Norwegian University of Life Sciences & Dept. de Biodiversidad y Gestión Ambiental Universidad de León Ås/León 2010 UMB Thesis number 2010: 01 ISSN 1503-1667 ISBN 978-82-575-0913-2 This thesis has been conducted as a PhD research co-supervision agreement between the Norwegian University of Life Sciences and the University of León (Spain). I acknowledge the effort of J. E. Swenson, E. de Luis Calabuig and E. Panero to succeed in establishing the agreement. PhD supervisors Prof. Jon E. Swenson (main supervisor) Department of Ecology and Natural Resource Management Norwegian University of Life Sciences Pb. 5003, 1432 Ås, Norway Dr. Ole-Gunnar Støen Department of Ecology and Natural Resource Management Norwegian University of Life Sciences Pb. 5003, 1432 Ås, Norway Prof. Miguel Delibes de Castro Estación Biológica de Doñana, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas Avenida Américo Vespucio s/n Isla de la Cartuja E-41092 Sevilla, Spain Adjudication committee Prof. -

Pan 1 Recent Advances in Elucidating the Function of Zebra Stripes

Pan 1 Recent Advances in Elucidating the Function of Zebra Stripes: Parasite Avoidance and Thermoregulation Do Not Resolve the Mystery Introduction Why are zebras striped? This question has baffled biologists for ages since the time of Darwin (Darwin 545). Although we remain far from an answer, past research was not done in vain. Currently, as much as 18 different theories have been proposed (Horváth et al. “EETSDNCZ” 1). These proposed explanations largely fall into four categories: 1) Predator avoidance through crypsis and various types of visual confusion (Ruxton 238), 2) reinforcement of social interactions (239), 3) ectoparasite deterrence (241), and 4) thermoregulation (239). Among the four groups of hypotheses, only the latter two have gained some support. The speculations that stripes help zebras blend in with tall grass (238), appear larger when in a group (237), or dazzle vertebrate predators like lions or spotted hyenas (238) were all but rejected because of the lack of empirical support and not because of the lack of trying (Caro et al. “TFOZS” 3; Larison et al. “HTZGIS” 3; Ruxton 238). Similarly, the idea that zebra stripes provide social benefits such as individual identification and bonding remains largely speculative (Ruxton 240), if not just outright rejected (Caro et al. “TFOZS” 3). Many of the hypotheses also do not actually suggest a fitness benefit but explain how the zebras interact (Ruxton 239). Therefore, they insufficiently explain why zebra stripes evolved in the first place. In contrast, overwhelming empirical evidence support the hypothesis that ‘zebra like’ stripes deter ectoparasites like glossinids and tabanids (Blaho et al. -

Benefits of Zebra Stripes: Behaviour of Tabanid Flies Around Zebras and Horses

Caro, T. , Argueta, Y., Briolat, E., Bruggink, J., Kasprowsky, M., Lake, J., Mitchell, M., Richardson, S., & How, M. (2019). Benefits of zebra stripes: behaviour of tabanid flies around zebras and horses. PLoS ONE, 14(2), [e0210831]. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210831 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record License (if available): CC BY Link to published version (if available): 10.1371/journal.pone.0210831 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via PLoS at DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210831. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ RESEARCH ARTICLE Benefits of zebra stripes: Behaviour of tabanid flies around zebras and horses 1 1 2 3 Tim CaroID *, Yvette Argueta , Emmanuelle Sophie Briolat , Joren Bruggink , 2 4 2 2 Maurice Kasprowsky , Jai Lake , Matthew J. Mitchell , Sarah RichardsonID , 4 Martin HowID 1 Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, University of California Davis, Davis, California, United States of America, 2 Centre for Ecology and Conservation Biosciences, College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Penryn, Cornwall, United Kingdom, 3 Aeres University of Applied Sciences, Almere, Netherlands, 4 School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, United Kingdom * [email protected] a1111111111 Abstract a1111111111 a1111111111 Averting attack by biting flies is increasingly regarded as the evolutionary driver of zebra a1111111111 stripes, although the precise mechanism by which stripes ameliorate attack by ectoparasites a1111111111 is unknown. -

Body Painting Type Analysis Based on Biomimicry Camouflage

International Journal of Architecture, Arts and Applications 2020; 6(1): 1-11 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ijaaa doi: 10.11648/j.ijaaa.20200601.11 ISSN: 2472-1107 (Print); ISSN: 2472-1131 (Online) Review Article Body Painting Type Analysis Based on Biomimicry Camouflage Eun-Young Park Department of Bioengineering, Graduate School of Konkuk University, Seoul, South Korea Email address: To cite this article: Eun-Young Park. Body Painting Type Analysis Based on Biomimicry Camouflage. International Journal of Architecture, Arts and Applications. Vol. 6, No. 1, 2020, pp. 1-11. doi: 10.11648/j.ijaaa.20200601.11 Received: November 26, 2019; Accepted: December 20, 2019; Published: January 7, 2020 Abstract: The purpose of this study is to establish a method and find a possible way of applying biomimicry camouflage in body painting. This study seeks a direction for the future of the beauty and art industry through biomimicry. For this study, we analyzed the works by classifying camouflage body painting into passive and active camouflage sections based on the application of biomimicry to the artificial camouflage system. In terms of detailed types, passive camouflage was classified into general resemblance and special resemblance, and active camouflage into adventitious resemblance and variable protective resemblance, and expression characteristics and type were derived. Passive camouflage is the work of the pictorial expressive technique using aqueous and oily body painting products. The general resemblance was expressed as a body painting of crypsis and camouflage strategies. The special resemblance is a mimicry in which the human body camouflages the whole figure of living organisms or inanimate objects. -

Antipredator Deception in Terrestrial Vertebrates

Current Zoology 60 (1): 16–25, 2014 Antipredator deception in terrestrial vertebrates Tim CARO* Department of Wildlife, Fish and Conservation Biology, and Center of Population Biology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA Abstract Deceptive antipredator defense mechanisms fall into three categories: depriving predators of knowledge of prey’s presence, providing cues that deceive predators about prey handling, and dishonest signaling. Deceptive defenses in terrestrial vertebrates include aspects of crypsis such as background matching and countershading, visual and acoustic Batesian mimicry, active defenses that make animals seem more difficult to handle such as increase in apparent size and threats, feigning injury and death, distractive behaviours, and aspects of flight. After reviewing these defenses, I attempt a preliminary evaluation of which aspects of antipredator deception are most widespread in amphibians, reptiles, mammals and birds [Current Zoology 60 (1): 16 25, 2014]. Keywords Amphibians, Birds, Defenses, Dishonesty, Mammals, Prey, Reptiles 1 Introduction homeotherms may increase the distance between prey and the pursuing predator or dupe the predator about the In this paper I review forms of deceptive antipredator flight path trajectory, or both (FitzGibbon, 1990). defenses in terrestrial vertebrates, a topic that has been Last, an antipredator defense may be a dishonest largely ignored for 25 years (Pough, 1988). I limit my signal. Bradbury and Vehrencamp (2011) state that “true scope to terrestrial organisms because lighting condi- deception occurs when a sender produces a signal tions in water are different from those in the air and whose reception will benefit it at the expense of the antipredator strategies often differ in the two environ- receiver regardless of the condition with which the sig- ments. -

Arbeitsvorhaben 2015/2016

^o_bfqpsloe^_bk=abo=cbiiltp = = = cbiiltp Û =molgb`qp= OMNRLOMNS= Herausgeber: Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin Wallotstraße 19 14193 Berlin Tel.: +49 30 89 00 1-0 Fax: +49 30 89 00 1-300 [email protected] wiko-berlin.de Redaktion: Angelika Leuchter Redaktionsschluss: 17. Juli 2015 Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung - Nicht-kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitung 3.0 Deutschland Lizenz INHALT VORWORT ________________________________ 4 L A I T H A L - SHAWAF _________________________ 6 D O R I T B A R - ON ____________________________ 8 TATIANA BORISOVA ________________________ 10 V I C T O R I A A . BRAITHWAITE __________________ 12 JANE BURBANK ____________________________ 14 ANNA MARIA BUSSE BERGER __________________ 16 T I M C A R O ________________________________ 18 M I R C E A C Ă RTĂ RESCU _______________________ 20 B A R B A R A A . CASPERS _______________________ 22 DANIEL CEFAÏ _____________________________ 24 INNES CAMERON CUTHIL L ___________________ 26 LORRAINE DASTON _________________________ 28 CLÉMENTINE DELISS ________________________ 30 HOLGER DIESSEL ___________________________ 32 ELHADJI IBRAHIMA DIO P ____________________ 34 PAULA DROEGE ____________________________ 36 DIETER EBERT _____________________________ 38 FINBARR BARRY FLOOD ______________________ 40 RAGHAVENDRA GADAGKAR __________________ 42 PETER GÄRDENFORS ________________________ 44 LUCA GIULIANI ____________________________ 46 SUSAN GOLDIN - MEADOW ____________________ 48 M I C H A E L D . GORDIN ________________________ 50 -

Body Size and Evolution of Motion Dazzle Coloration in Lizards

Behavioral The official journal of the ISBE Ecology International Society for Behavioral Ecology Behavioral Ecology (2017), 00(00), 1–8. doi:10.1093/beheco/arx128 Original Article Body size and evolution of motion dazzle coloration in lizards Gopal Murali and Ullasa Kodandaramaiah IISER-TVM Centre for Research and Education in Ecology and Evolution (ICREEE), School of Biology, Indian Institute of Science Education and Research Thiruvananthapuram, Maruthamala PO, Vithura, Thiruvananthapuram 695 551, India Received 4 April 2017; revised 2 July 2017; editorial decision 22 August 2017; accepted 13 September 2017. “Motion dazzle” patterns are a form of defensive coloration suggested to prevent successful capture during motion by causing preda- tors to misjudge the direction or speed of prey movement. Several studies have found results supporting this idea but little is known about the factors that favor the evolution of these antipredator colorations. A recent experimental study has suggested that the lon- gitudinal striped patterns on the body of lizards can redirect attacks to the tail via the motion dazzle effect. Using a virtual predation experiment with humans and a phylogenetic comparative analysis, we show that evolution of longitudinal striped coloration is associ- ated with prey size. Experiments showed that longitudinal stripes located at the anterior reduced lethal attacks (i.e., attacks directed to the anterior and centre) but this benefit was greater for shorter prey. Our comparative analysis revealed a negative association between stripe occurrence and body length but no association between stripes and body width. Overall, our results suggest that the dazzle effect produced by stripes is more advantageous in shorter lizards than in longer ones and that the error induced by stripes might be distributed along the axis parallel to the prey trajectory. -

Escape Distance in Ground-Nesting Birds Differs with Individual Level of Camouflage

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Escape distance in ground-nesting birds differs with individual level of camouflage AUTHORS Wilson-Aggarwal, J; Troscianko, J; Stevens, M; et al. JOURNAL American Naturalist DEPOSITED IN ORE 30 March 2016 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/20871 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication Escape distance in ground-nesting birds differs with individual level of camouflage Authors: J.K. Wilson-Aggarwal*1, J.T. Troscianko1, M. Stevens†1 and C.N. Spottiswoode2,3 Corresponding Authors: * [email protected] † [email protected] 1 Centre for Ecology & Conservation, College of Life & Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Penryn, Cornwall, TR10 9FE, UK. 2 University of Cambridge, Department of Zoology, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK 3 DST-NRF Centre of Excellence at the Percy FitzPatrick Institute, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa Key words Camouflage, background matching, escape behaviour, ground-nesting birds, incubation To be published as an article with supplementary materials in the expanded online edition. Includes: Abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, figure 1, figure 2, table 1, online appendix A, figure A1 and table A1. 1 Abstract Camouflage is one of the most widespread anti-predator strategies in the animal kingdom, yet no animal can match its background perfectly in a complex environment. Therefore, selection should favour individuals that use information on how effective their camouflage is in their immediate habitat when responding to an approaching threat. -

Establishing the Behavioural Limits for Countershaded Camouflage

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Establishing the behavioural limits for countershaded camoufage Olivier Penacchio1, Julie M. Harris1 & P. George Lovell2 Countershading is a ubiquitous patterning of animals whereby the side that typically faces the highest Received: 15 June 2017 illumination is darker. When tuned to specifc lighting conditions and body orientation with respect to Accepted: 20 September 2017 the light feld, countershading minimizes the gradient of light the body refects by counterbalancing Published: xx xx xxxx shadowing due to illumination, and has therefore classically been thought of as an adaptation for visual camoufage. However, whether and how crypsis degrades when body orientation with respect to the light feld is non-optimal has never been studied. We tested the behavioural limits on body orientation for countershading to deliver efective visual camoufage. We asked human participants to detect a countershaded target in a simulated three-dimensional environment. The target was optimally coloured for crypsis in a reference orientation and was displayed at diferent orientations. Search performance dramatically improved for deviations beyond 15 degrees. Detection time was signifcantly shorter and accuracy signifcantly higher than when the target orientation matched the countershading pattern. This work demonstrates the importance of maintaining body orientation appropriate for the displayed camoufage pattern, suggesting a possible selective pressure for animals to orient themselves appropriately to enhance crypsis. Te evolution of animal coloration is afected by several constraints including communication, thermoregulation, protection against ultra-violet radiation and visual camoufage1–3. Countershading is a patterning where the parts of the body that usually face the direction of maximum illumination, usually the back, are darker than parts facing in the opposite direction4,5. -

VRC 2018 Programme (PDF, 416Kb)

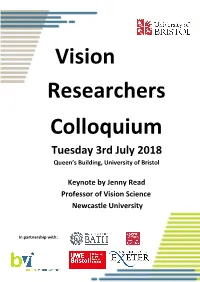

Vision Researchers Colloquium Tuesday 3rd July 2018 Queen’s Building, University of Bristol Keynote by Jenny Read Professor of Vision Science Newcastle University In partnership with: Vision Researchers Colloquium 2018 Programme 09:00 Registration, tea and coffee 09:30 Welcome by BVI Director, Professor David Bull Sessi Chaired by Professor Innes Cuthill, University of Bristol Kjernsmo, Karin, University of Bristol: Iridescence as camouflage? Impaired object 09:35 recognition in bumblebees 09:55 Daly, Ilse, University of Bristol: Complex gaze stabilisation in mantis shrimp 10:15 Robert, Theo, University of Exeter: Flexibility in bumblebees learning flights Talas, Laszlo, University of Bristol: The “Camouflage Machine”: Optimising patterns 10:35 for camouflage and visibility 10:55 Break – tea and coffee Sessio Chaired by Professor Darren Cosker, University of Bath 11:15 Saquil, Yassir, University of Bath: Generative models for semantic data exploration Gale, Ella, University of Bristol: Characterising and manipulating the learned 11:35 representation of visual data in deep-neural networks trained to classify images Kangin, Dimitry, University of Exeter: Reinforcement learning for vision-based 11:55 control Masullo, Alessandro, University of Bristol: CaloriNet: From silhouette to calorie 12:15 estimation in private environments 12:35 Lunch and poster presentations Sessio Chaired by Dr Natalie Hempel de Ibarra, University of Exeter Keynote: Jenny Read, Professor of Vision Science, Newcastle University: Of mantids 14:00 and men: Stereoscopic -

Merilaita, S., Scott-Samuel, N., & Cuthill, I. (2017). How Camouflage

Merilaita, S. , Scott-Samuel, N., & Cuthill, I. (2017). How camouflage works. Philosophical Transactions B: Biological Sciences, 372, 20160341. [20160341]. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2016.0341 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1098/rstb.2016.0341 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the final published version of the article (version of record). It first appeared online via The Royal Society Philpspphical Transactions at http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/372/1724/20160341#sec-14 . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. article template Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. doi:10.1098/not yet assigned How camouflage works Sami Merilaita1, Nicholas E. Scott-Samuel2, Innes C. Cuthill3 1 Department of Biosciences, Åbo Akademi University, Tykistökatu 6, FI-20520 Turku, Finland 2 Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Bristol, 12A Priory Road, Bristol BS8 1TN, UK 3 School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, 24 Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TQ, UK Keywords: defensive coloration, signal-to-noise ratio, crypsis, visual search, animal coloration *Author for correspondence ([email protected]). †Present address: Department of Biosciences, Åbo Akademi University, Tykistökatu 6, FI-20520 Turku, Finland Summary For camouflage to succeed, an individual has to pass undetected, unrecognized or untargeted, and so it is the processing of visual information that needs to be deceived. -

CEC Annual Report 2017

Field Course Fortnight photo competition winner – “Students and biodiversity” – Bahamas, Yin Tan PENRYN CAMPUS PENRYN Centre for Ecology and Conservation Annual Report 2017 animal silhouettes border out of green? double page spread? montage? StillWelcome growing in size and reputation The CEC continues to be an exemplar in sharing One of the books, The Tale of the Turtle and the science with our community (see Science in Plastic Jellyfish has already been translated into the Community). Our school’s programme French and Greek, with other languages pending. continued apace reaching 4,000 students across As the year ends, it sees 20 schools. We were again represented at the This year was yet again one of great success for the Centre for me passing the baton of Cornwall Show and Penryn Day. In Falmouth Ecology and Conservation. In the Student Guild Awards we were leadership of the Centre for Week our flagship event, Science in the Square crowned Department of the Year for the Cornwall Campuses. Ecology and Conservation saw 3,000 visitors treated to a veritable This not only evidences the excellence of our staff but the and CLES Cornwall to cornucopia of accessible science and then to end strength of the relationship with our students, particularly our Professor Dave Hodgson the year, the fourth annual Science of Christmas student representatives, who engage so strongly in our agenda of (pictured right). It has been my honour to serve event was hosted by Falmouth Polytechnic. 2017 codevelopment and improvement of educational content and process. as Director and work for such an amazing group saw the fruition of the Professor Penny Stories of students and staff.