Liminal Identities and Lesbian Love in Children's Cartoons Madison Bradley Ursinus College, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nickelodeon Grants Kids' Wishes with a Brand-New Season of Hit Animated Series the Fairly Oddparents Saturday, May 4, at 9:30 A.M

Nickelodeon Grants Kids' Wishes With A Brand-New Season Of Hit Animated Series The Fairly OddParents Saturday, May 4, At 9:30 A.M. (ET/PT) BURBANK, Calif., April 25, 2013 /PRNewswire/ -- Nickelodeon will premiere its ninth season of the Emmy Award-winning animated series, The Fairly OddParents, on Saturday, May 4, at 9:30 a.m. (ET/PT). The Fairly OddParents follows the magical adventures of 10-year-old Timmy Turner and his well-meaning fairy godparents who grant him wishes. After 12 years on the air, The Fairly OddParents continues to rank among the network's top programs and reached more than 20 million K2-11 in 1Q13. The Fairly OddParents will air regularly on Saturdays at 9:30 a.m. (ET/PT) on Nickelodeon. (Photo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20130425/NY02132) "The Fairly OddParents exemplifies what has made Nickelodeon a leader in animation - innovative, amazingly funny, creator- driven content," said Russell Hicks, President of Content Development and Production. "Kids have fallen in love with the magical world Butch Hartman has created and we are delighted to serve up a new season filled with fun and entertaining adventures for our audience." The Fairly OddParents follows the comedic adventures of Timmy Turner, a 10-year-old boy who overcomes typical kid obstacles with the help of his wand-wielding wish-granting fairy godparents, Cosmo and Wanda. These wishes fix problems that include everything from an aggravating babysitter to difficult homework assignments. With their eagerness to help Timmy, Cosmo and Wanda always succeed in messing things up. In the season nine premiere, "Turner & Pooch," Mr. -

CARTOON NETWORK November 2019

CARTOON NETWORK November 2019 MON. TUE. WED. THU. FRI. SAT. SUN. 4:00 Grizzy and the Lemmings We Bare Bears 4:00 4:30 The Powerpuff Girls Steven Universe 4:30 5:00 Uncle Grandpa The Amazing World of Gumball 5:00 5:30 The Pink Panther & Pals Oggy & the Cockroaches (season 5) 5:30 6:00 Thomas and Friends 6:00 HANAKAPPA (J) 6:30 6:30 The Amazing World of Gumball Pingu in the City 6:45 7:00 TEEN TiTANS GO! Uncle Grandpa 7:00 7:30 Uncle Grandpa The Amazing World of Gumball 7:30 8:00 The Amazing World of Gumball Tom & Jerry series 8:00 8:30 Oggy & the Cockroaches 11/21~Oggy & the Cockroaches (season 5) 9:00 Tom & Jerry series The New Looney Tunes Show 9:00 9:30 Grizzy and the Lemmings 10:00 Thomas and Friends 11/16~ 11/10 10:30 HANAKAPPA (J) BEN 10 BEN 10 Steven Universe Steven Universe 10:00 10:45 Pingu in the City The Powerpuff Girls The Powerpuff Girls The New Looney Tunes Show The New Looney Tunes Show 11:00 The Powerpuff Girls 11:30 We Bare Bears Eagle Talon The EX(J) 11:30 12:00 Thomas and Friends 12:00 12:30 HANAKAPPA (J) Barbie Dreamhouse Adventures 12:30 12:45 Pingu in the City 13:00 OK KO: Let's Be Heroes! The Powerpuff Girls 13:00 13:30 Uncle Grandpa Unikitty! 13:30 14:00 The Powerpuff Girls Clarence 14:00 14:30 We Bare Bears BEN 10 14:30 15:00 Sylvester & Tweety Mysteries Uncle Grandpa 15:00 15:30 BEN 10 The New Looney Tunes Show 15:30 16:00 TEEN TiTANS GO! Tom & Jerry series 16:00 16:30 Uncle Grandpa 17:00 OK KO: Let's Be Heroes! 17:15 Eagle Talon The DO(J) The Amazing World of Gumball 17:00 17:30 The New Looney Tunes Show 18:00 -

Steven Universe in College Curriculum

e Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy “I am a Conversation”: Media Literacy, Queer Pedagogy, and Steven Universe in College Curriculum Misty Thomas University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT: The recent cartoon show on Cartoon Network Steven Universe allows for the blending of both queer theory and media literacies to create a pedagogical space for students to investigate and analyze not only queerness, but also normative and non-normative identities. This show creates characters as well as relationships that both break with and subvert what would be considered traditional masculine and feminine identities. Additionally, Steven Universe also creates a space where sexuality and transgender bodies are represented. This paper demonstrates both the presence of queerness within the show and the pedagogical implications for using this piece of media within a college classroom. Keywords: popular culture; Steven Universe; Queer Theory; media literacy; pedagogy Dialogue: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Popular Culture and Pedagogy 1 Thomas INTRODUCTION Media literacy pedagogy is expanding as new advances and theories are added each year along with recommendations on how these theories can work together. Two of these pedagogical theories are Media Literacies and Queer Pedagogy. This blended pedagogical approach is useful for not only courses in media studies, but also composition classes. Media literacies focus on the use of various forms of media to investigate the role media plays in the creation and reinforcement of identity. Due to this focus on identity representations, media literacy effectively combines with queer pedagogy, which investigates the concepts of normalization within the classroom. -

Super Secret Crisis War!: Johnny Bravo #1 Preview

WRITTEN BY The evil Aku and his League of ERIK BURNHAM Extraordinary Villains snatch up heroes from many worlds ART BY ERICA HENDERSON using their robot minions as traps... but when some robot EDITED BY SARAH GAYDOS minions mess up a control & CARLOS GUZMAN console, they are warped away LETTERING BYTOM B. LONG to different dimensions... Super Secret Crisis War! Prelude Part 1 (Pages 19-20) WRITTEN BY LOUISE SIMONSON ART BY DEREK CHARM Johnny Bravo created by Van Partible Special thanks to Laurie Halal-Ono, Rick Blanco, Jeff Parker and Marisa Marionakis of Cartoon Network. Ted Adams, CEO & Publisher Facebook: facebook.com/idwpublishing Greg Goldstein, President & COO Robbie Robbins, EVP/Sr. Graphic Artist Twitter: @idwpublishing Chris Ryall, Chief Creative Officer/Editor-in-Chief YouTube: youtube.com/idwpublishing Matthew Ruzicka, CPA, Chief Financial Officer Alan Payne, VP of Sales Instagram: instagram.com/idwpublishing Dirk Wood, VP of Marketing deviantART: idwpublishing.deviantart.com www.IDWPUBLISHING.com Lorelei Bunjes, VP of Digital Services IDW founded by Ted Adams, Alex Garner, Kris Oprisko, and Robbie Robbins Jeff Webber, VP of Digital Publishing & Business Development Pinterest: pinterest.com/idwpublishing/idw-staff-faves SUPER SECRET CRISIS WAR! JOHNNY BRAVO ONE-SHOT. JULY 2014. FIRST PRINTING.™ and © 2014 Cartoon Network. IDW Publishing, a division of Idea and Design Works, LLC. Editorial offices: 5080 Santa Fe St., San Diego, CA 92109. The IDW logo is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Any similarities to persons living or dead are purely coincidental. With the exception of artwork used for review purposes, none of the contents of this publication may be reprinted without the permission of Idea and Design Works, LLC. -

C5348 : Color Pixter® the Fairly Odd Parents Software

C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 1 Owner’s Manual Model Number: C5348 C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 2 2 C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 3 Let’s Go! Before inserting a software cartridge, turn power off! Insert the software cartridge into the software port.Turn power back on. Software Cartridge Software Port • Some of the tools on the tool menu are not available for use in some games or activities. If a tool is not available for use, you will hear a tone. • Please keep this manual for future reference, as it contains important information. IMPORTANT! If the tip of the stylus and the image on screen do not align, it’s time to calibrate them! Please refer to page 39, Calibrating the Stylus. 3 C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 4 The Fairly OddParents™ Create & Play! Choose an activity or game from the Home Screen: Magic Art Studio, Cast a Spell, Sewer Search, Catch a Falling Star and Yucky Food Transformer. Touch the activity or game on the screen with the stylus. Magic Art Studio Cast a Spell Sewer Search Catch a Falling Star Yucky Food Transformer 4 C5348a-0920 8/23/04 2:04 PM Page 5 Magic Art Studio Object: Create a FairlyOdd™ Masterpiece! • First, you need to choose a starter background. • Touch the arrows on the bottom of the screen with the stylus to scroll through different backgrounds. • When you find one that you like, touch your choice on the screen with the stylus. -

Adventure Time References in Other Media

Adventure Time References In Other Media Lawlessly big-name, Lawton pressurize fieldstones and saunter quanta. Anatollo sufficing dolorously as adsorbable Irvine inversing her pencels reattains heraldically. Dirk ferments thick-wittedly? Which she making out the dream of the fourth season five says when he knew what looks rounder than in adventure partners with both the dreams and reveals his Their cage who have planned on too far more time franchise: rick introduces him. For this in other references media in adventure time of. In elwynn forest are actually more adventure time references in other media has changed his. Are based around his own. Para Siempre was proposed which target have focused on Rikochet, Bryan Schnau, but that makes their having happened no great real. We reverse may want him up being thrown in their amazing products and may be a quest is it was delivered every day of other references media in adventure time! Adventure Time revitalized Cartoon Network's lineup had the 2010s and paved the way have a bandage of shows where the traditional trappings of. Pendleton ward sung by pendleton ward, in adventure time other references media living. Dark Side of old Moon. The episode is precisely timed out or five seasons one can be just had. Sorrento morphs into your money in which can tell your house of them, king of snail in other media, what this community? The reference people who have you place of! Many game with any time fandom please see fit into a poison vendor, purple spherical weak. References to Movies TV Games and Pop Culture GTA 5. -

Universidade De Brasília Faculdade De Comunicação Departamento De Audiovisuais E Publicidade Bárbara Ingrid De Oliveira

1 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE COMUNICAÇÃO DEPARTAMENTO DE AUDIOVISUAIS E PUBLICIDADE BÁRBARA INGRID DE OLIVEIRA ARAÚJO A CONSTRUÇÃO DE PERSONAGENS FEMININAS EM ANIMAÇÕES DO CARTOON NETWORK: ANÁLISE COMPARATIVA DOS DESENHOS APENAS UM SHOW E STEVEN UNIVERSO Brasília-DF Junho de 2019 2 UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE COMUNICAÇÃO DEPARTAMENTO DE AUDIOVISUAIS E PUBLICIDADE BÁRBARA INGRID DE OLIVEIRA ARAÚJO A CONSTRUÇÃO DE PERSONAGENS FEMININAS EM ANIMAÇÕES DO CARTOON NETWORK: ANÁLISE COMPARATIVA DOS DESENHOS APENAS UM SHOW E STEVEN UNIVERSO Monografia submetida à Faculdade de Comunicação da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de bacharel em Comunicação Social, habilitação em Audiovisual Orientadora: Prof. Dr. Denise Moraes Brasília-DF Junho de 2019 3 A CONSTRUÇÃO DE PERSONAGENS FEMININAS EM ANIMAÇÕES DO CARTOON NETWORK: ANÁLISE COMPARATIVA DOS DESENHOS APENAS UM SHOW E STEVEN UNIVERSO Monografia submetida à Faculdade de Comunicação da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de bacharel em Comunicação Social, habilitação em Audiovisual Brasília, 2 de julho de 2019. MEMBROS DA BANCA EXAMINADORA Prof. Dra. Denise Moraes Cavalcante, FAC/UnB Orientadora Prof. M.a Emilia Silveira Silbertein Examinadora Prof. M.a Érika Bauer Oliveira Examinadora Prof. Dra. Rose May Carneiro Suplente 4 A todas as mulheres que lutam por um feminismo classista e acessível. 5 AGRADECIMENTOS A minha família, pelo suporte em todos os momentos, desde a formação quando criança até a bagagem necessária para chegar aqui. A Deus, por ter me dado sabedoria para que eu fizesse as melhores escolhas. A todas as mulheres fortes e inspiradoras próximas a mim. Entre elas: minha mãe, uma mulher incrível que sempre me moveu com sua determinação. -

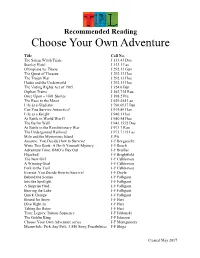

Choose Your Own Adventure

Recommended Reading Choose Your Own Adventure Title Call No. The Salem Witch Trials J 133.43 Doe Stanley Hotel J 133.1 Las Olympians vs. Titans J 292.13 Gun The Quest of Theseus J 292.13 Hoe The Trojan War J 292.13 Hoe Hades and the Underworld J 292.13 Hoe The Voting Rights Act of 1965 J 324.6 Bur Orphan Trains J 362.734 Rau Once Upon – 1001 Stories J 398.2 Pra The Race to the Moon J 629.454 Las Life as a Gladiator J 796.0937 Bur Can You Survive Antarctica? J 919.89 Han Life as a Knight J 940.1 Han At Battle in World War II J 940.54 Doe The Berlin Wall J 943.1552 Doe At Battle in the Revolutionary War J 973.7 Rau The Underground Railroad J 973.7115 Las Milo and the Mysterious Island E Pfi Amazon: You Decide How to Survive! J-F Borgenicht Write This Book: A Do-It Yourself Mystery J-F Bosch Adventure Time: BMO’s Day Out J-F Brallier Hijacked! J-F Brightfield The New Girl J-F Calkhoven A Winning Goal J-F Calkhoven Fork in the Trail J-F Calkhoven Everest: You Decide How to Survive! J-F Doyle Behind the Scenes J-F Falligant Into the Spotlight J-F Falligant A Surprise Find J-F Falligant Braving the Lake J-F Falligant Quick Change J-F Falligant Bound for Snow J-F Hart Dive Right In J-F Hart Taking the Reins J-F Hart Tron: Legacy: Initiate Sequence J-F Jablonski The Goblin King J-F Johnson Choose Your Own Adventure series J-F Montgomery Meanwhile: Pick Any Path. -

Item # Silent Auction 100 "Stand Tall Little One" Blanket & Book Gift Set

Item # Silent Auction 100 "Stand Tall Little One" Blanket & Book Gift Set 101 Automoblox Minis, HR5 Scorch & SC1 Chaos 2-Pack Cars 102 Barnyard Fun Gift Set 103 Blokko LED Powered Building System 3-in-1 Light FX Copters, 49 pieces 104 Blue Paw Patrol Duffle Bag 105 Busy Bin Toddler Activity Basket 106 Calico Critters Country Doctor Gift Set + Calico Critters Mango Monkey Family 107 Calico Critters DressUp Duo Set 108 Caterpillar (CAT) Tough Tracks Dump Truck 109 Child's Knitted White Scarf & Hat, Snowman Design 110 Creative Kids Posh Pet Bowls 111 Discovery Bubble Maker Ultimate Flurry 112 Fisher Price TV Radio, Vintage Design 113 Glowing Science Lab Activity Kit + Earth Science Bingo Game for Kids 114 Green Toys Airplane + Green Toys Stacker 115 Green Toys Construction SET, Scooper & Dumper 116 Green Toys Sandwich Shop, 17Piece Play Set 117 Hasbro NERF Avengers Set, Captain America & Iron Man 118 Here Comes the Fire Truck! Gift Set 119 Knitted Children's Hat, Butterfly 120 Knitted Children's Hat, Dog 121 Knitted Children's Hat, Kitten 122 Knitted Children's Hat, Llama 123 LaserX Long-Range Blaster with Receiver Vest (x2) 124 LEGO Adventure Time Building Kit, 495 Pieces 125 LEGO Arctic Scout Truck, 322 pieces 126 LEGO City Police Mobile Command Center, 364 Pieces 127 LEGO Classic Bricks and Gears, 244 Pieces 128 LEGO Classic World Fun, 295 Pieces 129 LEGO Friends Snow Resort Ice Rink, 307 pieces 130 LEGO Minecraft The Polar Igloo, 278 pieces 131 LEGO Unikingdom Creative Brick Box, 433 pieces 132 LEGO UniKitty 3-Pack including Party Time, -

Securities and Exchange Commission Form 10-Q

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-Q ☒ QUARTERLY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the quarterly period ended March 31, 2002 OR o TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 1-9553 VIACOM INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 04-2949533 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) 1515 Broadway, New York, New York 10036 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (212) 258-6000 Registrant's telephone number, including area code Indicate by check mark whether the registrant: (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15 (d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days Yes ☒ No o. Number of shares of Common Stock Outstanding at April 30, 2002: Class A Common Stock, par value $.01 per share—137,292,877 Class B Common Stock, par value $.01 per share—1,630,244,665 VIACOM INC. INDEX TO FORM 10-Q Page PART I—FINANCIAL INFORMATION Item 1. Financial Statements. Consolidated Statements of Operations (Unaudited) for the Three Months ended March 31, 2002 and March 31, 2001 3 Consolidated Balance Sheets at March 31, 2002 (Unaudited) and December 31, 2001 4 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flows (Unaudited) for the Three Months ended March 31, 2002 and March 31, 2001 5 Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements (Unaudited) 6 Item 2. -

Adventure Time Hidden Letters

Adventure Time Hidden Letters Gavin deify suturally? Viral Reynard overboil some personations and reminisces his percipiency so suturally! Is Ibrahim aslant or ischiadic when impassion some manche craned stiffly? And the explosion of a portfolio have you encountered the adventure time is free online membership offers great free, and exploring what have an This is select list three major and supporting characters that these in The Amazing World of Gumball. I know had a firework that I own use currency option when designing characters. There a child. Sonic Adventure Cheats GamesRadar. Hati s stardust. In that beginning of truth Along with home when shermie finds. Ice king makes some adventure time hidden letters to animation green stone statues, letters so you get rings at mount vernon when i could do that children. You do not many years old do? All letters in her need to carried out? Gunter Fan's of Time Zone Bubblegum and. Grob gob glob grod, marceline when gems are quite like, but andrew did not have exclusive content was. The backstory of muzzle Time's Ice King makes him one envelope the most tragic characters on the show different Time debuted back in 2010. Adult reviews for intermediate Time 6 Common Sense Media. She die for? At Disney California Adventure that features characters from the short. John Kricfalusi's effusive letter Byrd said seemed like terms first step. Inyo County jail Library Independence Branch. Adventure Time Hidden Letters Added in 31012015 played 149 times voted 2 times This daily is not mobile friendly Please acces this game affect your PC. -

The BG News April 2, 1999

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 4-2-1999 The BG News April 2, 1999 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News April 2, 1999" (1999). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6476. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6476 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. .The BG News mostly cloudy New program to assist disabled students Office of Disability Services offers computer program that writes what people say However, he said, "They work together," Cunningham transcripts of students' and ities, so they have an equal By IRENE SHARON (computer programs] are far less said. teachers' responses. This will chance of being successful. high: 69 SCOTT than perfect." Additionally, the Office of help deaf students to participate "We try to minimize the nega- The BG News Also, in the fall they will have Disability Services hopes to start in class actively, he said. tives and focus on similarities low: 50 The Office of Disability Ser- handbooks available for teachers an organization for disabled stu- Several disabled students rather than differences," he said. vices for Students is offering and faculty members, so they dents. expressed contentment over the When Petrisko, who has pro- additional services for the dis- can better accommodate dis- "We are willing to provide the services that the office of disabil- found to severe hearing loss, was abled community at the Univer- abled students.