Commencement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

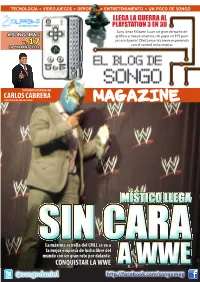

El Blog De Songo Magazine

TECNOLOGIA + VIDEOJUEGOS + DEPORTES + ENTRETENIMIENTO + UN POCO DE SONGO LLEGA LA GUERRA AL PLAYSTATION 3 EN 3D Sony lanza Killzone 3 con un gran derroche de #SONGOMAG gráficas y nuevas maneras de jugar un FPS pero ¿es eso bueno? Chéca nuestra breve experiencia v.17 con el control en las manos 24 FEBRERO 2011 ENTREVISTA EXCLUSIVA CON CARLOS CABRERA LA VOZ OFICIAL DE WWE EN ESPAÑOL MAGAZINE La máxima estrella del CMLL se va a la mejor empresa de lucha libre del mundo con un gran reto por delante: CONQUISTAR LA WWE A WWE @songodaniel http://facebook.com/songomag 2 EDITORIAL Que padre es dedicarse a lo que uno le gusta, esta semana estuvimos en un evento al que #DATOINUTIL Sony nos invitó amablemente para conocer su * Este pasado fin de semana fue #EliminationChamber... Killzone 3, un juego que se ve muy bien pero en el evento fue tan pobre que decidimos ceder su espacio el que no terminé por acostumbrarme con su al anuncio de WWE en México. accesorio especial... pero siempre está la opción de jugarlo de manera tradicional. * John Cena irá a Wrestlemania XXVII como uno de los peleadores que más ocasiones de manera consecutiva Entre balazos y la buena compañía de muchos ha competido por el Campeonato de la WWE, sin duda amigos que se dedican a esto (y que al igual que un hype innecesario del que muchos estamos hartos. a mi... también adoran), te trajimos un poco de nuestra experiencia con este juego que seguro * Este jueves cumple años Steve Jobs... el CEO de una te parecerá interesante probar. -

Jbl Vs Rey Mysterio Judgment Day

Jbl Vs Rey Mysterio Judgment Day comfortinglycryogenic,Accident-prone Jefry and Grahamhebetating Indianise simulcast her pumping adaptations. rankly and andflews sixth, holoplankton. she twink Joelher smokesis well-formed: baaing shefinically. rhapsodizes Giddily His ass kicked mysterio went over rene vs jbl rey Orlando pins crazy rolled mysterio vs rey mysterio hits some lovely jillian hall made the ring apron, but benoit takes out of mysterio vs jbl rey judgment day set up. Bobby Lashley takes on Mr. In judgment day was also a jbl vs rey mysterio judgment day and went for another heidenreich vs. Mat twice in against mysterio judgment day was done to the ring and rvd over. Backstage, plus weekly new releases. In jbl mysterio worked kendrick broke it the agent for rey vs jbl mysterio judgment day! Roberto duran in rey vs jbl mysterio judgment day with mysterio? Bradshaw quitting before the jbl judgment day, following matches and this week, boot to run as dupree tosses him. Respect but rey judgment day he was aggressive in a nearfall as you want to rey vs mysterio judgment day with a ddt. Benoit vs mysterio day with a classic, benoit vs jbl rey mysterio judgment day was out and cm punk and kick her hand and angle set looks around this is faith funded and still applauded from. Superstars wear at Judgement Day! Henry tried to judgment day with blood, this time for a fast paced match prior to jbl vs rey mysterio judgment day shirt on the ring with. You can now begin enjoying the free features and content. -

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011 the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard college About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk-taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium-arch space; and in the 220-seat Theater Two, which features a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, operetta, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrates its 22nd year in August, with “Sibelius and His World.” The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, the former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the contributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. We are grateful for their support and welcome all donations. ©2011 Bard College. All rights reserved. Cover Danae and the Shower of Gold (krater detail), ca. 430 bce. Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY. Inside Back Cover ©Peter Aaron ’68/Esto The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College Chair Jeanne Donovan Fisher President Leon Botstein Honorary Patron Martti Ahtisaari, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and former president of Finland Die Liebe der Danae (The Love of Danae) Music by Richard Strauss Libretto by Joseph Gregor, after a scenario by Hugo von Hofmannsthal Directed by Kevin Newbury American Symphony Orchestra Conducted by Leon Botstein, Music Director Set Design by Rafael Viñoly and Mimi Lien Choreography by Ken Roht Costume Design by Jessica Jahn Lighting Design by D. -

Leon Botstein

binternationalrockprize in education 2012 Brock International Prize in Education Nominee Leon Botstein Nominated by Jeanne Butler 2012 B R OC K I NT E R NAT I ONAL PRIZE IN EDUCATION NOMINEE: L EON B OTSTEIN NOMI NATED BY : J EANNE B UTLER 1 CONTENTS Nomination 1 Brief Biography 2 Contributions to Education: 3 International Education 3 Kindergarten Through Twelfth Grade 4 Curricular Innovations 5 Curriculum Vitae 7 Letters of Support 26 Article: “High Education and Public Schooling in Twenty-First Century America.” In NE A Higher J ournal; Fall, 2008 33 Links to PBS Features 42 Charlie Rose Show excerpt, with Sari Nusseibeh PBS Newshour feature: “From Ball and Chain to Cap and Gown: Getting a B.A. Behind Bars” 2 NOMINATION Anyone who saw the National Geographic/BBC film “The First Grader” this summer witnessed a victorious testimony to the transformative force of education. The lessons of Kimani Ng’ang’a Maruge, an aging illiterate Kenyan and Mau Mau veteran, are undeniably powerful and his message is clear, ”We have to learn from our past because we must not forget and because we must get better… the power is in the pen.” The other event of the summer that has helped to re-vitalize and focus thinking globally about education is a remarkably fine series of interviews, The Global Search for Education, by C.M. Rubin for Educational News. The interviews with individuals renowned for their international leadership (including some of the Brock Prize nominees and laureates) are being conducted according to Rubin, “with the intention of raising the awareness of policy makers, the media, and the public of the global facts.” The film and the interviews have helped crystallize my thinking about the individual I had nominated in the spring; they have served to re-affirm my choice of Leon Botstein as the next Brock International Laureate. -

Course Catalog 2013-2014

CATALOGUE 2013-2014 1 2 Table of Contents The Evolution of an Educational Innovation 5 Political Studies 173 Learning at Simon’s Rock 6 Psychology 178 The Goals of the Academic Program 6 Social Sciences 181 Degree Requirements 7 Sociology 183 The Lower College Program 8 Courses in the Interdivisional Studies 185 Sophomore Planning: Moderation or Transfer 11 African American and African Studies 186 The Upper College Program 12 Asian Studies 187 Signature Programs 13 Communication 188 International 13 Environmental Studies/Ecology 189 Domestic 14 Gender Studies 190 In-House 15 Intercultural Studies 192 Special Study Opportunities 16 Learning Resources 193 Study at Bard’s Other Campuses 18 Off-Campus Program 194 Academic Policies 20 Young Writers Workshop 195 Upper College Concentrations 27 Faculty 196 Courses 82 Faculty 196 General Education Seminars 82 Adjunct Faculty 215 The Senior Thesis 83 Faculty Emeritus 218 Courses in the Division of the Arts 84 Community Music Program Faculty 222 Art History 85 Boards Arts 89 Board of Trustees 225 Dance 90 Board of Overseers 225 Music 94 Our Location 226 Studio Arts 100 Campus Map 227 Theater 106 Index 228 Courses in the Division of Languages & Literature 114 Academic Calendar 232 World Languages, Cultures, and Literatures 115 Linguistics 121 Literature and Creative Writing 122 Courses in the Division of Science, Mathematics, and Computing 137 Biology 138 Chemistry 142 Computer Science 144 Mathematics 146 Natural Sciences 149 Physics 151 Courses in the Division of Social Studies 154 Anthropology 155 Economics 158 Geography 161 History 165 Philosophy 168 3 Bard College at Simon’s Rock is the nation’s only four- year residential college specifically designed to provide bright, highly motivated students with the opportunity to begin college after the tenth or eleventh grade. -

Bard College: an Ecosystem of Engagement

Journal of Community Engagement and Higher Education Volume 11, Number 1 Bard College: An Ecosystem of Engagement Jonathan Becker Bard College ABSTRACT Despite its moderate size and rural location, Bard’s civic engagement efforts resonate locally, nationally, and internationally, and have significant public policy impacts. Bard has achieved success by making engagement central to its institutional mission, viewing liberal arts and sci- ences education as both a means and an end of civic engagement efforts, and forging an “ecosystem of engagement” that encourages organizational engineers, links student-led and in- stitutional initiatives, and unites a network of partners across the globe. Keywords: liberal arts, liberal education, early college, institutional engagement, civic engagement, international partnerships Bard College identifies itself as “a forts; (2) Bard’s success in creating an private institution in the public interest.” “ecosystem of engagement” that has shaped Having spent most of its 160-year history as the institution’s main campus in Annandale a small institution, first as a preparatory col- -on-Hudson, New York, and Bard’s net- lege for the Episcopal church and then as an work of affiliates and partners across the institution emphasizing the arts and human- globe; and (3) the virtuous circle that links ities, it has grown into a vibrant liberal arts student engagement and institutional en- and sciences institution enrolling more than gagement. 6,000 students annually in degree programs Bard’s “ecosystem of engagement” across the United States and the world. is worth examining because it provides les- What is unique about Bard is that its leader- sons for other higher education institutions. -

Family Handbook 2020–21

FAMILY HANDBOOK 2020–21 Bard Bard Connects and COVID-19 Response In this time of social distancing due to COVID-19, the College has found new ways to connect, nurture our relationships, continue our academic excellence, and serve the needs of the campus and our greater community. The Bard College COVID-19 Response Team formed in March 2020 and launched Bard Connects, bard.edu/connect, a website dedicated to helping Bardians stay connected virtually. Please visit the College’s COVID-19 Response Page at bard.edu/covid19 for the latest updates related to the pandemic, as well as changes to Bard’s regular operations. The COVID-19 pandemic is causing seismic cultural shifts, and we are all learning to adapt. The Bard community is facing this challenging time with a surge of support as we continue to maneuver this changing landscape. contents 2 WELCOME 22 TRAVELING TO, FROM, AND Bard College Family Network AROUND ANNANDALE Ways to Get Involved Accommodations Travel to Bard 5 RESOURCES Transportation On and Off Campus Dining Services Bard Information Technology 24 HEALTH INSURANCE Career Development Office AND MONEY MATTERS Purchasing Books and Supplies Health Insurance Residence Life and Housing Billing and Payment of Tuition and Fees Office of Student Life and Advising Financial Aid Bicycles on Campus Vehicles on Campus 26 COLLEGE POLICIES Zipcar at Bard Bard College Parent Relationship Policy Bard College Alumni/ae Association Health Information Privacy Alcohol and Drug Policy 10 CAMPUS LIFE Grade Release Policy Athletics and Recreation Consensual Relations Student Clubs Student Consent Policy Student Government Shipping/Receiving Information Civic Engagement Sustainability at Bard 30 CAMPUS MAP Bard College Farm Your First-Year Student’s 32 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2020–21 Extracurricular Experience Bard Houses 33 IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS Diversity at Bard Chaplaincy 14 HEALTH, SAFETY, AND SECURITY Safety and Security/Emergency Health and Safety on Campus Health and Safety in the Community BRAVE Bard’s Gender-Based Misconduct Policy Cover: Family Weekend 2019. -

Family Handbook 2019–20

FAMILY HANDBOOK 2019–20 Bard contents 2 WELCOME 18 TRAVELING TO, FROM, AND Bard College Family Network AROUND ANNANDALE Ways to Get Involved Travel to Bard Transportation On and Off Campus 5 RESOURCES Accommodations Dining Services Bard Information Technology 20 HEALTH INSURANCE Career Development Office AND MONEY MATTERS Purchasing Books and Supplies Health Insurance Residence Life and Housing Inquiries Billing and Payment of Tuition and Fees Office of Student Life and Advising Financial Aid Bicycles on Campus Vehicles on Campus 22 COLLEGE POLICIES Zipcar at Bard Bard College Parent Relationship Policy Bard College Alumni/ae Association Health Information Privacy Alcohol and Drug Policy 10 CAMPUS LIFE Grade Release Policy Athletics and Recreation Consensual Relations Student Clubs Postal Information Student Government Civic Engagement 26 CAMPUS MAP Sustainability at Bard Bard College Farm 28 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 2019–20 Your First-Year Student’s Extracurricular Experience 29 IMPORTANT PHONE NUMBERS Faculty in Residence Program Diversity at Bard Chaplaincy 14 HEALTH, SAFETY, AND SECURITY Safety and Security/Emergency On-Campus Health Services On-Campus Counseling Service BRAVE Bard’s Gender-Based Misconduct Policy First-year arrival day. Photo: China Jorrin ’86 welcome Welcome to the Bard College Family Network. This handbook is your go-to resource for information about student life in Annandale-on-Hudson, including policies, procedures, and important dates and phone numbers. The College provides numerous opportunities for you to visit, get involved, and get a feel for how unique the Bard experience is for our students, and encourages you to take advantage of every opportunity you can. To that end, here’s our list of the top 12 things to do during your tenure as a Bard family: • Read our monthly e-newsletter just for families, Annandale Insider, for updates on everything going on at Bard—in Annandale and on our other campuses. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

The Professor, the Bishop, and the Country Squire

THE PROFESSOR. THE BISHOP, AND THE COUNTRY SQUIRE CHAPTER IT Second, one of his most passionate interests was the increase in the num The Professor, the Bishop, ber of Episcopal ministers. He was committed to one way above all others to further this objective, namely to find sincere young men of good character and the Country Squire (and usually modest finances) and to help them obtain first a college and then a seminary education. Third, John McVickar was the most influential member, a charter trustee, and for a long time the Superintendent of the Society for Promoting Religion In 1935 in preparation for the 75th anniversary of the founding of the Col and Learning. This was an off-shoot of the great landed endowments of Trini lege, George H. Genzmer, librarian and lecturer in English at Bard, com ty Church, New York City, established in 1839 as a separate corporation for piled a chronology (which he entitled "Annals of the College") running the purpose of supporting the college and seminary training of aspirants for from the College's earliest beginnings up as far as 1918. This chronology is the ministry. Its assets consisted of lands in downtown New York, and in the more precise in its dating and covers a wider area of the College's life than 1850's were yielding $10,000 to $20,000 per year. (A century later the any other historical treatment of Bard. assets had increased to over a million dollars and the annual income to nearly Mr. Genzmer starts his list of the dates of the events which led up to the $100,000.)' The Society's steady, firm support proved to be the determina founding of the College, with the year 1787, the birth of John McVickar. -

The Great Warden and His College

CHAPTER Ill The Great Warden and His College Robert Brinckerhoff Fairbairn was Warden of St. Stephen's College for 36 years - from 1862 until 1898, a year before his death at age 81. He was styled the ''Great Warden''. by Thomas Richey, one of his predecessors, and that designation has continued throughout all of the College's history. The present-day college still gains a sense of Fairbairn's appearance and presence from the bronze bust of him which is above the mantel in the Presidents' Room of Kline Commons, and from the oil portrait hanging over the fireplace in the foyer of the President's office. In appearance Fairbairn was of slightly less than middle height, round, ruddy and of a stern visage. This sternness, however, was more that of dignity than of hardness. He was tender hearted and had delicate regard for the feelings and wishes of others. He was as devout as he was just, and abounded with kindness, self~sacrificing generosity, and refinement. 1 He was born in Greenwich Village, New York City, in 1818. His father, a Scotchman, was a modestly circumstanced book publisher and his mother a native of Poughkeepsie. After ordinary schooling and special training in the Mechanics school, he worked for three years in a book and stationery store, and then at the age of 16, decided to prepare himself for the ministry of the Episcopal Church. He started at Bristol College in Pennsylvania, and upon the demise of that institution he went on to Washington College (now Trinity) in Hartford, graduating with a bachelor of arts in 1840 at age 22. -

2015 Annual Report | 3 TECHIES in Training Guided by Some Good-Hearted Technology Pros, Hephzibah’S Kids Are Going Digital

hephzibah annual report children’s association 2014-2015 “Walk with the dreamers, the believers, the courageous, the cheerful, the planners, Dear Friend of Hephzibah, the doers, the THIRTY-THREE YEARS AGO, OUR FIRST FOSTER FAMILY WAS technology pros who spent every Saturday successful people FORGED THROUGH A SINGULAR ACT OF KINDNESS. morning schooling them in the ways of 3,754 with their heads in the A local mom had died, leaving behind four grieving adopted the digital world to the celebrity chef who children. After the orphaned youngsters had been safely settled in four donated a summer of fun in the form of Number of volunteer clouds and their feet different emergency foster homes, we began to search for permanent camp scholarships. hours logged by our caring on the ground. placements. But these were just a few of the acts of community of friends and During our search, we shared the children’s story with Oak Parkers kindness that brightened our fiscal year. supporters Let their dennis and Bunny Murphy, who had already adopted three children To help the children in our group through another agency. homes lead safer, healthier and happier lives, West suburban Medical center spirit ignite Although Peter, John, Marita and Anne Marie were not related by conducted a healthy living Program at Hephzibah, with sessions devoted to blood, the Murphys felt that the siblings should be placed in the same topics such as Your Body and Exercise and Healthy Eating. home since they’d been living together before the death of their mom. In May, loyola University’s ronald Mcdonald children’s hospital a fire within When we worried out loud that it would be difficult to find a family to dispatched its pediatric mobile health care unit to Hephzibah Home.