Local Character-Based Metaphors in Fairy Tales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eucharist and Temptation in Hansel and Gretel

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, July 2018, Vol. 8, No. 7, 1007-1014 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2018.07.003 D DAVID PUBLISHING Ordinary and Special Breads: Eucharist and Temptation in Hansel and Gretel Judith Lanzendorfer University of Findlay, Ohio, USA This article focuses on how Hansel and Gretel, collected by Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm in Children’s and Household Tales (1812) should be seen as more than a folktale for small children; it can, instead, be read as a highly theological work related to the Calvinist view of the Eucharist and directed more to young adults and adults. The Grimm brothers, who were strict Calvinists, viewed the tales as being useful in instilling moral lessons to children. As such, Hansel and Gretel can be seen as highlighting the tension between Calvinist and Catholic perspectives on the Eucharist. It is important when teaching the text to consider this culturally relative context. Doing so helps to highlight the original didactic purpose for Children’s and Household Tales and how we can revisit and reclaim the moral initiative of the book in a modern context. Keywords: Grimm, Calvinist, Eucharist, folktale There have been many articles written about Hansel and Gretel, published by Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm in 1812 in Children’s and Household Tales. Points of analysis have focused on gender and age (Henneberg, 2010), to the effect that the tale has on the psychological development of the audience members (Wittmann, 2011) to manifestations of the tale in modern media (Rudy & Greenhill, 2014). Perhaps the most influential articles and books, though, are those by Jack Zipes, including the modern English translation of Children’s and Household Tales (2014), to “Who’s Afraid of the Brother’s Grimm: Socialization and Politicization Through Fairy Tales” (1979-1980) to the “Use and Abuse of Folk and Fairy Tales with Children” (1977). -

Hansel and Gretel by Michele L

2017-2018 Blinn College Theatre Season Lights Out: A Season of Dark Tales Division of Visual/Performing Arts and Kinesiology Brenham Campus Hansel and Gretel By Michele L. Vacca Based on the Fairy Tale by the Brothers Grimm Resource Guide This resource guide serves as an educational starting point to understanding and enjoying Michele L. Vacca’ s Hansel and Gretel. With this in mind, please note that the interpretations of this theatrical work may differ from the original source content. Public Performances November 16-18………………………………………………………………………..7:00 PM November 19…………………………………………………………………………….....2:00 PM Elementary Preview Performances November 16 & 17…………………………………….10:00 AM & 1:00 PM Tickets can be purchased in advance online at www.blinn.edu/BoxOffice, by calling 979-830-4024, or by emailing [email protected] Directed by Brad Nies Technical Theatre Direction by Kevin Patrick Costume, Makeup, and Hair Design by Jennifer Patrick Produced by Special Arrangement with Classics on Stage! The Synopsis In an attempt to have enough to eat during a great famine, a woodcutter and his abusive second wife decide to abandon their two children in the woods. After being left to die, little Hansel and Gretel discover a large cottage built of gingerbread, cakes, and delicious candies. The tired and hungry children begin to eat the candy house, but they are unaware that it is owned by a bloodthirsty and horrible witch! Characters The Narrator Hansel Gretel Father Stepmother Miss Hagatha Grundilly Sweetbriar Rasputin Dizzy Shibboleth, Hagatha’s Broom Boo-Boo, Dizzy’s Broom Modern Adaptations of Hansel and Gretel Books A Tale Dark and Grimm by Adam Gidwitz The Magic Circle by Donna Jo Napoli Gingerbread House by Laura Biggs and Sarah Steinbrenner The True Story of Hansel and Gretel by Louise Murphy Newspaper Articles “On the Trail of Hansel and Gretel in Germany” by David G. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

The Influence of External and Individual Factors on the Folktales of the Brothers Grimm

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2017 Apr 20th, 10:30 AM - 11:45 AM Subjective Retelling: The Influence of External and Individual Factors on the Folktales of the Brothers Grimm Katherine R. Woodhouse St. Mary's Academy Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, Folklore Commons, and the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Woodhouse, Katherine R., "Subjective Retelling: The Influence of External and Individual actF ors on the Folktales of the Brothers Grimm" (2017). Young Historians Conference. 22. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2017/oralpres/22 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. 1 SUBJECTIVE RETELLING: THE INFLUENCE OF EXTERNAL AND INDIVIDUAL FACTORS ON THE FOLKTALES OF THE BROTHERS GRIMM Katie Woodhouse PSU Challenge Honors History of Modern Europe December 14, 2016 2 The folktales of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm are, if nothing else, iconic. Since first publishing Kinder-und Hausmärchen, or Children’s and Household Tales, in 1812, their stories have been read, told, watched, and referenced all over the world. The Brothers Grimm were not the original authors of their famous stories; instead, they primarily considered -

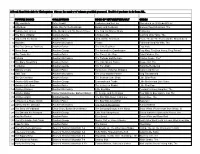

5-Plagues-Reading-Spine

Mr A, Mr C and Mr D Present… Reading Reconsidered Reading Spine Text Selector for Primary Schools Contents The 5 Plagues of a Developing Reader p3 Creation of the List & p4 Application to Long Term Plans Years 1-2 List p5-8 Years 3-4 List p9-11 Years 5-6 List p12-16 Other Books to Consider p17-20 Other Resources p21 The 5 Plagues of the Developing Reader In his book ‘Reading Reconsidered’, Doug Lemov points out that there are five types of texts that children should have access to in order to successfully navigate reading with confidence. These are complex beyond a lexical level and demand more from the reader than other types of books. Read his blog article here: http://teachlikeachampion.com/blog/on-text-complexity-and-reading-part-1- the-five-plagues-of-the-developing-reader/ Archaic Language The vocabulary, usage, syntax and context for cultural reference of texts over 50 or 100 years old are vastly different and typically more complex than texts written today. Students need to be exposed to and develop proficiency with antiquated forms of expression to be able to hope to read James Madison, Frederick Douglass and Edmund Spenser when they get to college. Non-Linear Time Sequences In passages written exclusively for students—or more specifically for student assessments— time tends to unfold with consistency. A story is narrated in a given style with a given cadence and that cadence endures and remains consistent, but in the best books, books where every aspect of the narration is nuanced to create an exact image, time moves in fits and start. -

The Significance of the Numbers Three, Four, and Seven in Fairy Tales, Folklore, And

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Honors Projects Undergraduate Research and Creative Practice 2014 The iS gnificance of the Numbers Three, Four, and Seven in Fairy Tales, Folklore, and Mythology Alonna Liabenow Grand Valley State University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Liabenow, Alonna, "The iS gnificance of the Numbers Three, Four, and Seven in Fairy Tales, Folklore, and Mythology" (2014). Honors Projects. 418. http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/honorsprojects/418 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research and Creative Practice at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Liabenow 1 Alonna Liabenow HNR 499 Senior Project Final The Significance of the Numbers Three, Four, and Seven in Fairy Tales, Folklore, and Mythology INTRODUCTION “Once upon a time … a queen was sitting and sewing by a window with an ebony frame. While she was sewing, she looked out at the snow and pricked her finger with the needle. Three drops of blood fell onto the snow” (Snow White 81). This is a quote which many may recognize as the opening to the famous fairy tale Snow White. But how many would take notice of the number three in the last sentence of the quote and question its significance? Why, specifically, did three drops of blood fall from the queen’s finger? The quote from Snow White is just one example of many in which the number three presents itself as a significant part of the story. -

First 100 Stories for Story Listening Stories Beniko Mason First

First 100 Stories for Story Listening stories Beniko Mason first I have been telling fairy tales and folktales from around the world in class as an English lesson since 1990. The combination of listening to stories and reading books has helped my students do well on tests without output or grammar studies. Story- Listening is so powerful that students improve rapidly in listening comprehension and acquire many words. There are countless stories in the world, but I happen to like Grimm Brothers’ house- hold tales. Almost all stories start with, “Once upon a time…” “Once upon a time there was a rich king.” “Once upon a time there were three brothers.” “Once upon a time there was a soldier.” They always start with an introduction of a main character. These stories are very suitable for story-listening lessons in different ways. The stories have interesting content; they are written in rich language; there are many different situations, problems, and characters; and they have stood the test of time. I have gathered here the first 100 easier stories for you to choose from to use for your classes. I will only give you the titles. You can download them from any sites that have the collection of Great Grimm Brothers’ household tales. These stories are not just for children. They deal with many different themes that children may not understand yet, such as deception, loyalty, and true love. Thus, story-listening is not just for children, but for adults also. Story-Listening can be used for any age and also at any levels of proficiency. -

Read Aloud Schedule from Modg KGRD

A Read Aloud Schedule for Kindergarten: Choose the number of columns you think you need. Don't feel you have to do them ALL. PICTURE BOOKS COLLECTIONS BOOK OF VIRTUES/PERRAULT GRIMM 1 Billy and Blaze Peter Rabbit Androcles and the Lion Allerleirauh [or All-Kinds-Of-Fur] 2 Little Bear Make Way for the Ducklings Beauty and the Beast Bremen Town Musicians, The 3 Bedtime for Frances Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel The Cap that Mother Made Cinderella 4 The Story of Babar Curious George Chicken Little Cunning Little Tailor, The 5 Angus and the Ducks Another Potter Jack and the Beanstalk Elves, The [or The Elves and the Shoemaker]* 6 Madeline Another McCloskey Please Fisherman and His Wife, The 7 The Five Chinese Brothers Another Burton The Little Red Hen Frau Holle 8 Stone Soup Another George The Ant and the Grasshopper Frog King, The [Iron Henry; Frog Prince]* 9 The Empty Pot Another Potter The Three Little Pigs Gold-Children, The 10 Petunia Another McCloskey The Tortoise and the Hare Golden Goose, The* 11 The Story About Ping Another Burton The Little Steam Engine Goose-Girl, The 12 Corduroy Another George Try, Try, Again Hans the Hedgehog 13 Millions of Cats Another Potter To the Little Girls that Wriggles Hansel and Gretel* 14 Little Toot Another McCloskey The Crow and the Pitcher King Thrushbeard 15 The Ox Cart Man Another Burton The Sermon to the Birds Little Briar-Rose 16 Another-Billy and Blaze Another George Diamonds and Toads Little Brother and Little Sister 17 Another-Little Bear Another Potter The Velveteen Rabbit Little Red-Cap 18 Another-Frances Another McCloskey Little Boy Blue Peasant's Clever Daughter, The 19 Another-Babar Calico Wonder Horse, Burton (library) St. -

Cinderella and Other Fairy Tales As Secular Scripture in Contemporary America and Russia Kate Christine Moore Koppy Purdue University

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Open Access Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2015 Cinderella and Other Fairy Tales as Secular Scripture in Contemporary America and Russia Kate Christine Moore Koppy Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations Recommended Citation Koppy, Kate Christine Moore, "Cinderella and Other Fairy Tales as Secular Scripture in Contemporary America and Russia" (2015). Open Access Dissertations. 1488. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/open_access_dissertations/1488 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Graduate School Form 30 Updated 1/15/2015 PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Thesis/Dissertation Acceptance This is to certify that the thesis/dissertation prepared By Kate Christine Moore Koppy Entitled Cinderella and Other Fairy Tales as Secular Scripture in Contemporary America and Russia For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Is approved by the final examining committee: Charles Ross Chair Shaun Hughes Jeffrey Turco John P. Hope To the best of my knowledge and as understood by the student in the Thesis/Dissertation Agreement, Publication Delay, and Certification Disclaimer (Graduate School Form 32), this thesis/dissertation adheres to the provisions of Purdue University’s “Policy of Integrity in Research” and the use of copyright material. Approved by Major Professor(s): Charles Ross Approved by: Charles Ross 10/07/2015 Head of the Departmental Graduate Program Date CINDERELLA AND OTHER FAIRY TALES AS SECULAR SCRIPTURE IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICA AND RUSSIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University by Kate C. -

Christian Themes in German Fairy Tales Nikolaus Foulkrod Cedarville University, [email protected]

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2014 yS mposium Apr 16th, 11:00 AM - 2:00 PM Christian Themes in German Fairy Tales Nikolaus Foulkrod Cedarville University, [email protected] Grant Friedrich Cedarville University, [email protected] Jen Johnson Cedarville University, [email protected] Nathaniel Burrell Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the German Literature Commons Foulkrod, Nikolaus; Friedrich, Grant; Johnson, Jen; and Burrell, Nathaniel, "Christian Themes in German Fairy Tales" (2014). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 7. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2014/poster_presentations/7 This Poster is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Literary Analysis • “Deeper meaning resides in the fairy Christian Themes in German Fairy Tales tales told to me in my childhood than in the truth that is taught by life.” (F. Schiller qtd. in Bettelheim, 1976) “Das Mädchen ohne “Die Alte im Wald” “Der Wolf und der “Der Schneider im • G. Ronald Murphy (2000), the Hände” (“The Old Woman in the Forest”) Fuchs” Himmel” author of the book The Owl, the (“The Girl with no Hands”) (“The Wolf and the Fox”) (“The Tailor in Heaven”) Raven, and the Dove, explores the Christian themes and elements in a • White Dove (Luke 3:22) few of the well‐known Grimm fairy • Mercy (Hebrews 4:16) • Prayer (Luke 11:9‐10; • Gluttony (Genesis 25:30‐ • Concept of Heaven (John tales. -

Giant List of Folklore Stories Vol. 6: Children's

The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 6 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay Skim and Scan The Giant List of Folklore Stories Folklore, Folktales, Folk Heroes, Tall Tales, Fairy Tales, Hero Tales, Animal Tales, Fables, Myths, and Legends. Vol. 6: Children’s Presented by Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The fastest, most effective way to teach students organized multi-paragraph essay writing… Guaranteed! Beginning Writers Struggling Writers Remediation Review 1 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay – Guaranteed Fast and Effective! © 2018 The Giant List of Stories - Vol. 6 Pattern Based Writing: Quick & Easy Essay The Giant List of Folklore Stories – Vol. 6 This volume is one of six volumes related to this topic: Vol. 1: Europe: South: Greece and Rome Vol. 4: Native American & Indigenous People Vol. 2: Europe: North: Britain, Norse, Ireland, etc. Vol. 5: The United States Vol. 3: The Middle East, Africa, Asia, Slavic, Plants, Vol. 6: Children’s and Animals So… what is this PDF? It’s a huge collection of tables of contents (TOCs). And each table of contents functions as a list of stories, usually placed into helpful categories. Each table of contents functions as both a list and an outline. What’s it for? What’s its purpose? Well, it’s primarily for scholars who want to skim and scan and get an overview of the important stories and the categories of stories that have been passed down through history. Anyone who spends time skimming and scanning these six volumes will walk away with a solid framework for understanding folklore stories. Here are eight more types of scholars who will just love these lists. -

Ebook Download Collected Grimm Tales

COLLECTED GRIMM TALES PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Carol Ann Duffy,Tim Supple | 272 pages | 04 Sep 2003 | FABER & FABER | 9780571221424 | English | London, United Kingdom Collected Grimm Tales PDF Book To ask other readers questions about Collected Grimm Tales , please sign up. The Jew Among the Thorns Sign up for free here. Both were given special dispensations for studying law at the University of Marburg. Showing Franz Xaver von Schonwerth. The Six Servants The Ungrateful Son. The Little Peasant Clever Hans Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were the oldest in a family of five brothers and one sister. The King of the Golden Mountain The Riddle Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano were good friends of the brothers and wanted to publish folk tales, so they asked the brothers to collect oral tales for publication. Their state of mind made them more Realists than Romantics. Simonmeredith rated it it was amazing Nov 09, The Complete Pelican Shakespeare. Another snake appears and heals the dead snake with three leaves, and they both leave. The Grimms collected many old books and asked friends and acquaintances in Kassel to tell tales and to gather stories from others. The stories of magic and myth gathered by the Brothers Grimm have become part of the way children—and adults—learn about the vagaries of the real world. September 20, , Berlin and Wilhelm Carl Grimm b. Highly recommended. Collected Grimm Tales Writer A good point is that several more unusual stories have been included, but these are largely a little less exciting than those which are better known. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.