Three Tall Women in 1994

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

A Delicate Balance

PEEK BEHIND THE SCENES OF A DELICATE BALANCE Compiled By Lotta Löfgren To Our Patrons Most of us who attend a theatrical performance know little about how a play is actually born to the stage. We only sit in our seats and admire the magic of theater. But the birthing process involves a long period of gestation. Certainly magic does happen on the stage, minute to minute, and night after night. But the magic that theatergoers experience when they see a play is made possible only because of many weeks of work and the remarkable dedication of many, many volunteers in order to transform the text into performance, to move from page to stage. In this study guide, we want to give you some idea of what goes into creating a show. You will see the actors work their magic in the performance tonight. But they could not do their job without the work of others. Inside you will find comments from the director, the assistant director, the producer, the stage manager, the set -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 0521542332 - The Cambridge Companion to Edward Albee Edited by Stephen Bottoms Table of Contents More information CONTENTS List of illustrations page ix Notes on contributors xi Acknowledgments xv Notes on the text xvi Chronology xvii 1 Introduction: The man who had three lives 1 stephen bottoms 2 Albee’s early one-act plays: “A new American playwright from whom much is to be expected” 16 philip c. kolin 3 Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?: Toward the marrow 39 matthew roudane´ 4 “Withered age and stale custom”: Marriage, diminution, and sex in Tiny Alice, A Delicate Balance, and Finding the Sun 59 john m. clum 1 5 Albee’s 3 /2: The Pulitzer plays 75 thomas p. adler 6 Albee’s threnodies: Box-Mao-Box, All Over, The Lady from Dubuque, and Three Tall Women 91 brenda murphy 7 Minding the play: Thought and feeling in Albee’s “hermetic” works 108 gerry mccarthy vii © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521542332 - The Cambridge Companion to Edward Albee Edited by Stephen Bottoms Table of Contents More information contents 8 Albee’s monster children: Adaptations and confrontations 127 stephen bottoms 9 “Better alert than numb”: Albee since the eighties 148 christopher bigsby 10 Albee stages Marriage Play: Cascading action, audience taste, and dramatic paradox 164 rakesh h. solomon 11 “Playing the cloud circuit”: Albee’s vaudeville show 178 linda ben-zvi 12 Albee’s The Goat: Rethinking tragedy for the 21st century 199 j. ellen gainor 13 “Words; words...They’re such a pleasure.” (An Afterword) 217 ruby cohn 14 Borrowed time: An interview with Edward Albee 231 stephen bottoms Notes on further reading 251 Select bibliography 253 Index 259 viii © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org. -

Past Productions

Past Productions 2017-18 2012-2013 2008-2009 A Doll’s House Born Yesterday The History Boys Robert Frost: This Verse Sleuth Deathtrap Business Peter Pan Les Misérables Disney’s The Little The Importance of Being The Year of Magical Mermaid Earnest Thinking Only Yesterday Race Laughter on the 23rd Disgraced No Sex Please, We're Floor Noises Off British The Glass Menagerie Nunsense Take Two 2016-17 Macbeth 2011-2012 2007-2008 A Christmas Carol Romeo and Juliet How the Other Half Trick or Treat Boeing-Boeing Loves Red Hot Lovers Annie Doubt Grounded Les Liaisons Beauty & the Beast Mamma Mia! Dangereuses The Price M. Butterfly Driving Miss Daisy 2015-16 Red The Elephant Man Our Town Chicago The Full Monty Mary Poppins Mad Love 2010-2011 2006-2007 Hound of the Amadeus Moon Over Buffalo Baskervilles The 39 Steps I Am My Own Wife The Mountaintop The Wizard of Oz Cats Living Together The Search for Signs of Dancing At Lughnasa Intelligent Life in the The Crucible 2014-15 Universe A Chorus Line A Christmas Carol The Real Thing Mid-Life! The Crisis Blithe Spirit The Rainmaker Musical Clybourne Park Evita Into the Woods 2005-2006 Orwell In America 2009-2010 Lend Me A Tenor Songs for a New World Hamlet A Number Parallel Lives Guys And Dolls 2013-14 The 25th Annual I Love You, You're Twelve Angry Men Putnam County Perfect, Now Change God of Carnage Spelling Bee The Lion in Winter White Christmas I Hate Hamlet Of Mice and Men Fox on the Fairway Damascus Cabaret Good People A Walk in the Woods Spitfire Grill Greater Tuna Past Productions 2004-2005 2000-2001 -

Use of Surrealistic Techniques in Edward Albee's Plays

Use of Surrealistic Techniques in Edward Albee’s Plays Submitted by: Muqaddas Javed Roll No. 13 Supervised by Sohail Ahmed Saeed Assistant Professor Department of English Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (English Literature) Session: 2010-13 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH The Islamia University of Bahawalpur ABSTRACT This research will trace various surrealistic techniques present in Edward Albee’s plays. Surrealism has been a very important movement of art and literature before World War II, it has greatly influenced the modern and post-modern theories of literature. Edward Albee is the first American playwright who has incorporated these techniques in his plays, hence revolutionizing the American theatre. Edward Albee is best known as a dramatist belonging to the Theatre of the Absurd. This research will initially explore the surrealistic techniques evident in the absurd plays of Edward Albee, after that it will identify the same techniques as being used in some of the other plays of Albee that fall under the category of realism or expressionism. This study aim to examine the surrealistic themes, motifs, stylistic techniques and other stage devices that appear again and again in Albee’s work; giving it a distinctive trait. This research will throw light on the fact that Albee’s works are not nihilistic rather he critically evaluates the modern human condition in order to break the modern materialistic myths of success. This research intends to examine Albee’s purpose of using different surrealistic techniques and their effect on the audience. In conclusion this study will try to prove that through use of surrealistic techniques Albee has experimented with different forms of playwriting. -

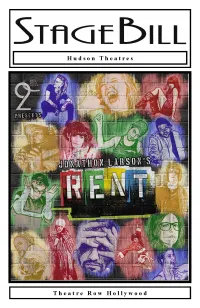

RENT Program

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Remember the first time you were inspired by a performance? The first time that your eyes opened just a little bit wider to try to capture and record everything you were seeing? Maybe it was your first Broadway show, or the first film that really grabbed you. Maybe it was as simple as a third-grade performance. It’s hard to forget that initial sense of wonder and sudden realization that the world might just contain magic . This is the sort of experience the 2Cents Theatre Group is trying to create. Classic performances are hard to define, but easy to spot. Our Goal is to pay homage and respect to the classics, while simultaneously adding our own unique 2 Cents to create a free-standing performance piece that will bemuse, inform, and inspire. 2¢ Theatre Group is in residence at the Hudson Theatre, at 6539 Santa Monica Boulevard. You can catch various talented members of the 2 Cent Crew in our Monthly Cabaret at the Hudson Theatre Café . the second Sunday of each Month. also from 2Cents AT THE HUDSON… TICKETS ON SALE NOW! May 30 - June 30 EACH WEEK FEATURING LIVE PRE-SHOW MUSIC BY: Thurs 5/30 - Stage 11 Sun 6/2 - Anderson William Thurs 6/6 - 30 North SuN 6/9 - Kelli Debbs Thurs 6/13 - TBD Sun 6/16 - Lee Wahlert Thurs 6/20 - TBD Sun 6/23 - TBD Thurs 6/27 - Fire Chief Charlie Sun 6/30 - Chris Duquee Cody Lyman Kristen Boulé & 2Cents Theatre Board of Directors with Michael Abramson at the Hudson Theatres present Book, Music & Lyrics by Jonathan Larson Dedrick Bonner Kate Bowman Amber Bracken Ariel Jean Brooker Brian -

Edward Albee's at Home at The

CAST OF CHARACTERS TROY KOTSUR*............................................................................................................................PETER Paul Crewes Rachel Fine Artistic Director Managing Director RUSSELL HARVARD*, TYRONE GIORDANO..........................................................................................JERRY AND AMBER ZION*.................................................................................................................................ANN JAKE EBERLE*...............................................................................................................VOICE OF PETER JEFF ALAN-LEE*..............................................................................................................VOICE OF JERRY PAIGE LINDSEY WHITE*........................................................................................................VOICE OF ANN *Indicates a member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of David J. Kurs Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Artistic Director Production of ACT ONE: HOMELIFE ACT TWO: THE ZOO STORY Peter and Ann’s living room; Central Park, New York City. EDWARD ALBEE’S New York City, East Side, Seventies. Sunday. Later that same day. AT HOME AT THE ZOO ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION STAFF STARRING COSTUME AND PROPERTIES REHEARSAL STAGE Jeff Alan-Lee, Jack Eberle, Tyrone Giordano, Russell Harvard, Troy Kotsur, WARDROBE SUPERVISOR SUPERVISOR INTERPRETER COMBAT Paige Lindsey White, Amber Zion Deborah Hartwell Courtney Dusenberry Alek Lev -

Albee, Edward. Three Tall Women. 1994. a Frustrated Ninety-Two Year Old Woman Reveals Three Arduous and Painful Stages of Her Life

Drama Albee, Edward. Three Tall Women. 1994. A frustrated ninety-two year old woman reveals three arduous and painful stages of her life. Beckett, Samuel. Waiting for Godot. 1952. Two tramps wait eternally for the elusive Godot in this first success of the Theater of The Absurd. Bernstein, Leonard. West Side Story. 1957. The Jets and Sharks battle it out in song and dance as Tony and Maria fall in love in this musical based on Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet. Christie, Agatha. Mousetrap. 1954. Stranded in a boarding house during a snowstorm, a group of strangers discovers a murderer in their midst. Coward, Noel. Blithe Spirit. 1941. A ghost troubles a novelist's second marriage. Fugard, Athol. Master Harold and the Boys. 1982. Hally, a precocious white South African teenager, lashes out at two older black friends who are substitute figures for his alcoholic father. Hansberry, Lorraine. Raisin in the Sun. 1959. The sudden appearance of money tears an African American family apart. Hellman, Lillian. Little Foxes. 1939. Members of the greedy and treacherous Hubbard family compete with each other for control of the mill that will bring them riches in the post-Civil War South. Ibsen, Henrik. A Doll's House. 1879. Nora, one of feminism's great heroines, steps off her pedestal and encounters the real world. Ionesco, Eugene. Rhinoceros. 1959. The subject is conformity; the treatment is comedy and terror. Kushner, Tony. Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes. Pt.1, Millennium Approaches (1992); Pt.2, Perestroika (1993). Kushner chronicles AIDS in America during the Reagan era. -

Interface Semiotics in the Dramaturgy of Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SZTE Doktori Értekezések Repozitórium... Ph.D. Dissertation Theses Interface Semiotics in the Dramaturgy of Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee Réka Mónika Cristian Szeged 2001 A. Objectives and Structure The topic of the present dissertation is the dramaturgy of two modem American playwrights, Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee. The aim is to map the common features of their works in the context of semiotic textual exchange between the two oeuvres and of the biographical background of the playwrights in the context of a dramatic interface of the two authors. The scope of the Albee-Williams dramatic interface is to explain both oeuvres through an internal patterning of events and characters by deriving concepts of the one (Williams) into the other (Albee). The study of both oeuvres provides the visualization of the enigmas, of the invisible patterns that work to build the intertextual Williams-Albee bind. The invisible in one play is a trope of representation in another play within the same oeuvre. One play is or might well be the other discourse of the other play both in the case of the same author and in case of two different authors. This trans-substantiation is present in the form of the dramatic intertext or, to be more precise - due to the biographical implication - of the dramatic interface. The influence of Williams on Albee’s works had been expressed by many literary critics, as well as by Albee himself The dramatic interface of the two authors is mapped with the theoretical help of semiotics, psychoanalysis, theories of myth, symbols and gender approaches. -

Newton Grisham Library Play Script List -By Author

Newton Grisham Library Play Script List -by Author BIN # PLAY # TITLE AUTHOR # MEN # WOMEN # CHILDREN OTHER 73 1570 Manhattan Class Company Class 1 Acts 1991-1992 161 2869 The Boys from Siam Connolly, John Austin 2 161 2876 Fugue Thuna, Lee 3 5 74 1591 Acrobatics Aaron, Joyce; Tarlo, Luna 96 1957 June Groom Abbot, Rick 3 6 99 2016 Play On! Abbot, Rick 3 7 103 2080 Turn For The Nurse, A Abbot, Rick 5 5 30 699 Three Men On A Horse Abbott, G. And J.C. Holm 11 4 34 802 Green Julia Ableman, Paul 2 133 2457 Tabletop Ackerman, Rob 5 1 86 1793 Batting Cage, The Ackermann, Joan 1 3 86 1798 Marcus Is Walking Ackermann, Joan 3 2 88 1825 Off The Map Ackermann, Joan 3 2 101 2051 Stanton's Garage Ackermann, Joan 4 4 10 227 Farewell, Farewell Eugene Ackland, Rodney; Vari, John 3 6 84 1776 Lighting Up The Two-Year Old Aerenson, Benjie 3 167 2970 Dark Matters Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto 3 1 168 2982 King of Shadows Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto 2 2 169 2998 The Muckle Man Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto 5 2 169 3007 Rough Magic Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto 7 5 doubling 101 2054 Edgar Lee Masters' Spoon River Anthology Aidman, Charles 3 2 101 2054 Spoon River Anthology Aidman, Charles [Adapt. By] 3 2 149 2686 Green Card Akalaitis, JoAnne 6 5 10 221 Fragments Albee, Edward 4 4 19 436 Marriage Play Albee, Edward 1 1 26 604 Seascape Albee, Edward 2 2 30 705 Tiny Alice Albee, Edward 4 1 34 800 The Zoo Story and The Sandbox: Two Short Plays Albee, Edward 34 800 Sandbox, The Albee, Edward 3 2 44 1066 Counting the Ways and Listening: Two Plays Albee, Edward 44 1066 Counting The Ways -

Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding Also Play, the Booklet Presents a Description of the Prinipal Characters Mormons

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 835 CS 508 902 AUTHOR Carr, John C. TITLE "Angels in America Part 1: Millennium Approaches." Spotlight on Theater Notes. INSTITUTION John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE [95) NOTE 17p.; Produced by the Performance Plus Program, Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding also provided by the Kennedy Center Corporate Fund. For other guides in this series, see CS 508 903-906. PUB TYPE Guides General (050) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Acquired Immune Defi-:ency Syndrome; Acting; *Cultural Enrichment; *Drama; Higher Education; Homophobia; Homosexuality; Interviews; Playwriting; Popular Culture; Program Descriptions; Secondary Education; United States History IDENTIFIERS American Myths; *Angels in America ABSTRACT This booklet presents a variety of materials concerning the first part of Tony Kushner's play "Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes." After a briefintroduction to the play, the booklet presents a description of the prinipal characters in the play, a profile of the playwright, information on funding of the play, an interview with the playwright, descriptions of some of the motifs in the play (including AIDS, Angels, Roy Cohn, and Mormons), a quiz about plays, biographical information on actors and designers, and a 10-item list of additional readings. (RS) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. ****):***:%****************************************************)%*****)%* -

Pam Mackinnon Announces Inaugural Season As Artistic Director of American Conservatory Theater

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Kevin Kopjak, Charles Zukow Associates |415.296.0677 | [email protected] Press photos and kits: act-sf.org/press PAM MACKINNON ANNOUNCES INAUGURAL SEASON AS ARTISTIC DIRECTOR OF AMERICAN CONSERVATORY THEATER The 2018–19 season includes Lynn Nottage’s 2017 Pulitzer Prize–winning drama, SWEAT; Jaclyn Backhaus’s ingenious and provocative telling of 19th-century American explorers, MEN ON BOATS; Edward Albee’s wildly imaginative and satirical Pulitzer Prize–winning comedy, SEASCAPE; Mfoniso Udofia’s achingly poignant drama, HER PORTMANTEAU; Lauren Yee’s exploration of cultural identity, global politics, and basketball, THE GREAT LEAP; and Kate Hamill’s rollicking new stage adaptation of William Thackeray’s classic novel, VANITY FAIR The final production of the 2018–19 season to be announced at a later date A Christmas Carol returns after another successful run in 2017 SAN FRANCISCO (April 3, 2018)—Tony, Obie, and Drama Desk Award winner Pam MacKinnon, the incominG artistic director of American Conservatory Theater (A.C.T.), has unveiled her inaugural season at the helm of San Francisco’s premier nonprofit theater company. The 2018–19 season includes Lynn NottaGe’s 2017 Pulitzer Prize–winninG drama, SWEAT; Jaclyn Backhaus’s inGenious and provocative tellinG of 19th-century American explorers, MEN ON BOATS; Edward Albee’s wildly imaGinative and satirical Pulitzer Prize–winninG comedy, SEASCAPE; Mfoniso Udofia’s achinGly poiGnant drama HER PORTMANTEAU; Lauren Yee’s exploration of cultural identity, global politics, and basketball, THE GREAT LEAP; and Kate Hamill’s rollickinG new staGe adaptation of William Thackeray’s classic novel, VANITY FAIR.