Arxiv:Astro-Ph/9906240V1 14 Jun 1999 Nteeouinr Ttso Estars Be Fabregat Juan of Status Evolutionary the on Orsodneto De- Correspondence to Is Issue Main the Question

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's up This Month – December 2019 These Pages Are Intended to Help You Find Your Way Around the Sky

WHAT'S UP THIS MONTH – DECEMBER 2019 THESE PAGES ARE INTENDED TO HELP YOU FIND YOUR WAY AROUND THE SKY The chart above shows the night sky as it appears on 15th December at 21:00 (9 o’clock) in the evening Greenwich Meantime Time (GMT). As the Earth orbits the Sun and we look out into space each night the stars will appear to have moved across the sky by a small amount. Every month Earth moves one twelfth of its circuit around the Sun, this amounts to 30 degrees each month. There are about 30 days in each month so each night the stars appear to move about 1 degree. The sky will therefore appear the same as shown on the chart above at 10 o’clock GMT at the beginning of the month and at 8 o’clock GMT at the end of the month. The stars also appear to move 15º (360º divided by 24) each hour from east to west, due to the Earth rotating once every 24 hours. The centre of the chart will be the position in the sky directly overhead, called the Zenith. First we need to find some familiar objects so we can get our bearings. The Pole Star Polaris can be easily found by first finding the familiar shape of the Great Bear ‘Ursa Major’ that is also 1 sometimes called the Plough or even the Big Dipper by the Americans. Ursa Major is visible throughout the year from Britain and is always easy to find. This month it is in the north east. -

MESSIER 13 RA(2000) : 16H 41M 42S DEC(2000): +36° 27'

MESSIER 13 RA(2000) : 16h 41m 42s DEC(2000): +36° 27’ 41” BASIC INFORMATION OBJECT TYPE: Globular Cluster CONSTELLATION: Hercules BEST VIEW: Late July DISCOVERY: Edmond Halley, 1714 DISTANCE: 25,100 ly DIAMETER: 145 ly APPARENT MAGNITUDE: +5.8 APPARENT DIMENSIONS: 20’ Starry Night FOV: 1.00 Lyra FOV: 60.00 Libra MESSIER 6 (Butterfly Cluster) RA(2000) : 17Ophiuchus h 40m 20s DEC(2000): -32° 15’ 12” M6 Sagitta Serpens Cauda Vulpecula Scutum Scorpius Aquila M6 FOV: 5.00 Telrad Delphinus Norma Sagittarius Corona Australis Ara Equuleus M6 Triangulum Australe BASIC INFORMATION OBJECT TYPE: Open Cluster Telescopium CONSTELLATION: Scorpius Capricornus BEST VIEW: August DISCOVERY: Giovanni Batista Hodierna, c. 1654 DISTANCE: 1600 ly MicroscopiumDIAMETER: 12 – 25 ly Pavo APPARENT MAGNITUDE: +4.2 APPARENT DIMENSIONS: 25’ – 54’ AGE: 50 – 100 million years Telrad Indus MESSIER 7 (Ptolemy’s Cluster) RA(2000) : 17h 53m 51s DEC(2000): -34° 47’ 36” BASIC INFORMATION OBJECT TYPE: Open Cluster CONSTELLATION: Scorpius BEST VIEW: August DISCOVERY: Claudius Ptolemy, 130 A.D. DISTANCE: 900 – 1000 ly DIAMETER: 20 – 25 ly APPARENT MAGNITUDE: +3.3 APPARENT DIMENSIONS: 80’ AGE: ~220 million years FOV:Starry 1.00Night FOV: 60.00 Hercules Libra MESSIER 8 (THE LAGOON NEBULA) RA(2000) : 18h 03m 37s DEC(2000): -24° 23’ 12” Lyra M8 Ophiuchus Serpens Cauda Cygnus Scorpius Sagitta M8 FOV: 5.00 Scutum Telrad Vulpecula Aquila Ara Corona Australis Sagittarius Delphinus M8 BASIC INFORMATION Telescopium OBJECT TYPE: Star Forming Region CONSTELLATION: Sagittarius Equuleus BEST -

Messier Plus Marathon Text

Messier Plus Marathon Object List by Wally Brown & Bob Buckner with additional objects by Mike Roos Object Data - Saguaro Astronomy Club Score is most numbered objects in a single night. Tiebreaker is count of un-numbered objects Observer Name Date Address Marathon Obects __________ Tiebreaker Objects ________ SEQ OBJECT TYPE CON R.A. DEC. RISE TRANSIT SET MAG SIZE NOTES TIME M 53 GLOCL COM 1312.9 +1810 7:21 14:17 21:12 7.7 13.0' NGC 5024, !B,vC,iR,vvmbM,st 12.. NGC 5272, !!,eB,vL,vsmbM,st 11.., Lord Rosse-sev dark 1 M 3 GLOCL CVN 1342.2 +2822 7:11 14:46 22:20 6.3 18.0' marks within 5' of center 2 M 5 GLOCL SER 1518.5 +0205 10:17 16:22 22:27 5.7 23.0' NGC 5904, !!,vB,L,eCM,eRi, st mags 11...;superb cluster M 94 GALXY CVN 1250.9 +4107 5:12 13:55 22:37 8.1 14.4'x12.1' NGC 4736, vB,L,iR,vsvmbM,BN,r NGC 6121, Cl,8 or 10 B* in line,rrr, Look for central bar M 4 GLOCL SCO 1623.6 -2631 12:56 17:27 21:58 5.4 36.0' structure M 80 GLOCL SCO 1617.0 -2258 12:36 17:21 22:06 7.3 10.0' NGC 6093, st 14..., Extremely rich and compressed M 62 GLOCL OPH 1701.2 -3006 13:49 18:05 22:21 6.4 15.0' NGC 6266, vB,L,gmbM,rrr, Asymmetrical M 19 GLOCL OPH 1702.6 -2615 13:34 18:06 22:38 6.8 17.0' NGC 6273, vB,L,R,vCM,rrr, One of the most oblate GC 3 M 107 GLOCL OPH 1632.5 -1303 12:17 17:36 22:55 7.8 13.0' NGC 6171, L,vRi,vmC,R,rrr, H VI 40 M 106 GALXY CVN 1218.9 +4718 3:46 13:23 22:59 8.3 18.6'x7.2' NGC 4258, !,vB,vL,vmE0,sbMBN, H V 43 M 63 GALXY CVN 1315.8 +4201 5:31 14:19 23:08 8.5 12.6'x7.2' NGC 5055, BN, vsvB stell. -

Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer Observations of the Evolution of Massive Star-Forming Regions

The Astrophysical Journal, 744:130 (24pp), 2012 January 10 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/744/2/130 C 2012. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. WIDE-FIELD INFRARED SURVEY EXPLORER OBSERVATIONS OF THE EVOLUTION OF MASSIVE STAR-FORMING REGIONS X. P. Koenig1,4,D.T.Leisawitz1, D. J. Benford1, L. M. Rebull2, D. L. Padgett1, and R. J. Assef3,4 1 NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA 2 Spitzer Science Center (SSC), California Institute of Technology, M/S 220-6, 1200 East California Boulevard, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 3 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, MS 169-530, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA Received 2011 July 8; accepted 2011 October 18; published 2011 December 22 ABSTRACT We present the results of a mid-infrared survey of 11 outer Galaxy massive star-forming regions and 3 open clusters with data from the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE). Using a newly developed photometric scheme to identify young stellar objects and exclude extragalactic contamination, we have studied the distribution of young stars within each region. These data tend to support the hypothesis that latter generations may be triggered by the interaction of winds and radiation from the first burst of massive star formation with the molecular cloud material leftover from that earlier generation of stars. We dub this process the “fireworks hypothesis” since star formation by this mechanism would proceed rapidly and resemble a burst of fireworks. We have also analyzed small cutout WISE images of the structures around the edges of these massive star-forming regions. -

August 13 2016 7:00Pm at the Herrett Center for Arts & Science College of Southern Idaho

Snake River Skies The Newsletter of the Magic Valley Astronomical Society www.mvastro.org Membership Meeting President’s Message Saturday, August 13th 2016 7:00pm at the Herrett Center for Arts & Science College of Southern Idaho. Public Star Party Follows at the Colleagues, Centennial Observatory Club Officers It's that time of year: The City of Rocks Star Party. Set for Friday, Aug. 5th, and Saturday, Aug. 6th, the event is the gem of the MVAS year. As we've done every Robert Mayer, President year, we will hold solar viewing at the Smoky Mountain Campground, followed by a [email protected] potluck there at the campground. Again, MVAS will provide the main course and 208-312-1203 beverages. Paul McClain, Vice President After the potluck, the party moves over to the corral by the bunkhouse over at [email protected] Castle Rocks, with deep sky viewing beginning sometime after 9 p.m. This is a chance to dig into some of the darkest skies in the west. Gary Leavitt, Secretary [email protected] Some members have already reserved campsites, but for those who are thinking of 208-731-7476 dropping by at the last minute, we have room for you at the bunkhouse, and would love to have to come by. Jim Tubbs, Treasurer / ALCOR [email protected] The following Saturday will be the regular MVAS meeting. Please check E-mail or 208-404-2999 Facebook for updates on our guest speaker that day. David Olsen, Newsletter Editor Until then, clear views, [email protected] Robert Mayer Rick Widmer, Webmaster [email protected] Magic Valley Astronomical Society is a member of the Astronomical League M-51 imaged by Rick Widmer & Ken Thomason Herrett Telescope Shotwell Camera https://herrett.csi.edu/astronomy/observatory/City_of_Rocks_Star_Party_2016.asp Calendars for August Sun Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat 1 2 3 4 5 6 New Moon City Rocks City Rocks Lunation 1158 Castle Rocks Castle Rocks Star Party Star Party Almo, ID Almo, ID 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 MVAS General Mtg. -

PUBLIC OBSERVING NIGHTS the William D. Mcdowell Observatory

THE WilliamPUBLIC D. OBSERVING mcDowell NIGHTS Observatory FREE PUBLIC OBSERVING NIGHTS WINTER Schedule 2019 December 2018 (7PM-10PM) 5th Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Oribion Nebula (M42), Beehive Cluster (M44), Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884) 12th Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Oribion Nebula (M42), Beehive Cluster (M44), Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884) 19th Moon, Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Oribion Nebula (M42), Beehive Cluster (M44), Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884) 26th Moon, Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Oribion Nebula (M42), Beehive Cluster (M44), Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884)? January 2019 (7PM-10PM) 2nd Moon, Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Sirius, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Orion Nebula (M42), Open Cluster (M35) 9th Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Sirius, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Orion Nebula (M42), Open Cluster (M35) 16 Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Sirius, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Orion Nebula (M42), Open Cluster (M35) 23rd, Moon, Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Sirius, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Orion Nebula (M42), Beehive Cluster (M44), Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884) 30th Moon, Mars, Uranus, Neptune, Sirius, Almach (double star), Pleiades (M45), Andromeda Galaxy (M31), Orion Nebula (M42), Beehive Cluster (M44), Double Cluster (NGC 869 & 884) February 2019 (7PM-10PM) 6th -

Astronomy Magazine Special Issue

γ ι ζ γ δ α κ β κ ε γ β ρ ε ζ υ α φ ψ ω χ α π χ φ γ ω ο ι δ κ α ξ υ λ τ μ β α σ θ ε β σ δ γ ψ λ ω σ η ν θ Aι must-have for all stargazers η δ μ NEW EDITION! ζ λ β ε η κ NGC 6664 NGC 6539 ε τ μ NGC 6712 α υ δ ζ M26 ν NGC 6649 ψ Struve 2325 ζ ξ ATLAS χ α NGC 6604 ξ ο ν ν SCUTUM M16 of the γ SERP β NGC 6605 γ V450 ξ η υ η NGC 6645 M17 φ θ M18 ζ ρ ρ1 π Barnard 92 ο χ σ M25 M24 STARS M23 ν β κ All-in-one introduction ALL NEW MAPS WITH: to the night sky 42,000 more stars (87,000 plotted down to magnitude 8.5) AND 150+ more deep-sky objects (more than 1,200 total) The Eagle Nebula (M16) combines a dark nebula and a star cluster. In 100+ this intense region of star formation, “pillars” form at the boundaries spectacular between hot and cold gas. You’ll find this object on Map 14, a celestial portion of which lies above. photos PLUS: How to observe star clusters, nebulae, and galaxies AS2-CV0610.indd 1 6/10/10 4:17 PM NEW EDITION! AtlAs Tour the night sky of the The staff of Astronomy magazine decided to This atlas presents produce its first star atlas in 2006. -

Binocular Challenge Here

AHSP Binocular Observing Award Compiled by Phil Harrington www.philharrington.net • To qualify for the BOA pin, you must see 15 of the following 20 binocular targets. Check off each as you spot them. Seen # Object Const. Type* RA Dec Mag Size Nickname 1. M13 Her GC 16 41.7 +36 28 5.9 16' Great Hercules Globular 2. M57 Lyr PN 18 53.6 +33 02 9.7 86"x62" Ring Nebula 3. Collinder 399 Vul AS 19 25.4 +20 11 3.6 60' Coathanger/Brocchi’s Cluster 3.1 4. Albireo Cyg Dbl 19 30.7 +27 57 35” Color Contrasting Double 5.1 5. M27 Vul PN 19 59.6 +22 43 8.1 8’x6’ Dumbbell Nebula 6. NGC 6992 Cyg SNR 20 56.4 +31 43 - 60'x8 Veil Nebula (east) 7. NGC 7000 Cyg BN 20 58.8 +44 20 - 120'x100' North America Nebula 8. M15 Peg GC 21 30.0 +12 10 7.5 12’ Great Pegasus Cluster 9. M39 Cyg OC 21 32.2 +48 26 4.6 32' 10. Barnard 168 Cyg DN 21 53.2 +47 12 - 100'x10' West of Cocoon Nebula 11. IC 5146 Cyg BN/OC 21 53.5 +47 16 - 12'x12' Cocoon Nebula 12. M110 And Gx 00 40.4 +41 41 10 17’x10’ 13. M32 And Gx 00 42.8 +40 52 10 8’x6’ 14. M31 And Gx 00 42.8 +41 16 4.5 178’ Andromeda Galaxy 15. NGC 457 Cas OC 01 19.1 +58 20 6.4 13’ Owl Cluster/ET Cluster 16. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Maui Stargazing Observing List

MAUI STARGAZING OBSERVING LIST FEBRUARY TELESCOPE OBJECTS FEBRUARY LASER POINTER OBJECTS GALAXIES ASTERISMS M 31 (Andromeda) Belt (Orion) M 32 (Andromeda) Big Dipper (Ursa Major (Rising) M 33 Pinwheel (Triangulum) Great Square (Pegasus) M 81 (Ursa Major) Guardians of the Pole (Ursa Minor) M 82 Ursa Major) Milk Dipper (Orion) M 101 (Andromeda) Little Dipper (Ursa Minor) Shield (Orion) MUTLIPLE STAR SYSTEM Sickle (Leo) Castor (Gemini) Sword (Orion) W or M or Chair (Cassiopeia) BRIGHT NEBULAE Winter Circle M 1 Crab (Taurus) Winter Triangle M 42 Orion (Orion) CONSTELLATIONS GLOBULAR STAR CLUSTER Andromeda (Chained Maiden) M 79 (Lepus) Aries (Ram) Auriga (Charioteer) OPEN STAR CLUSTERS Cancer (Crab) Caldwell 41 Hyades (Taurus) (Bare Eye) Canis Major (Big Dog) M 38 Starfish (Auriga) Canis Minor (Little Dog) M 41 Heart of the Dog (Canis Major) Cassiopeia (Queen of Ethiopia) M 44 Beehive (Cancer) Cepheus (King of Ethiopia) M 45 Pleiades (Taurus) Cetus (Whale) NGC 869 Double Cluster (Perseus) Columba (Dove) NGC 884 Double Cluster (Perseus) Eridanus (River) NGC 1976 Trapezuim (Orion) Hydra (Water Snake) rising NGC 7789 Caroline’s Rose (Cassiopeia) Leo (Lion) rising Lepus (Hare) BARE EYE OBJECTS Orion (Hunter) Rising Satellites and Meteor Showers! Pegasus (Flying Horse) Perseus (Hero) FIRST MAGNITUDE STARS Taurus (The Bull) Achernar (Eridanus) Triangulum (Triangle) Aldebaran (Taurus) Ursa Major (Big Bear) Betelgeuse (Orion) Ursa Minor (Little Bear) Bellatrix (Orion) Capella (Auriga the Charioteer) Canopus (Carinae the Keel) Pollux (Gemini) Procyon (Canis Minor) Regulus (Leo) Rigel (Orion) Sirius (Canis Major) . -

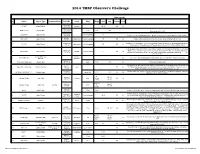

2014 Observers Challenge List

2014 TMSP Observer's Challenge Atlas page #s # Object Object Type Common Name RA, DEC Const Mag Mag.2 Size Sep. U2000 PSA 18h31m25s 1 IC 1287 Bright Nebula Scutum 20'.0 295 67 -10°47'45" 18h31m25s SAO 161569 Double Star 5.77 9.31 12.3” -10°47'45" Near center of IC 1287 18h33m28s NGC 6649 Open Cluster 8.9m Integrated 5' -10°24'10" Can be seen in 3/4d FOV with above. Brightest star is 13.2m. Approx 50 stars visible in Binos 18h28m 2 NGC 6633 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.6m integrated 27' 205 65 Visible in Binos and is about the size of a full Moon, brightest star is 7.6m +06°34' 17h46m18s 2x diameter of a full Moon. Try to view this cluster with your naked eye, binos, and a small scope. 3 IC 4665 Open Cluster Ophiuchus 4.2m Integrated 60' 203 65 +05º 43' Also check out “Tweedle-dee and Tweedle-dum to the east (IC 4756 and NGC 6633) A loose open cluster with a faint concentration of stars in a rich field, contains about 15-20 stars. 19h53m27s Brightest star is 9.8m, 5 stars 9-11m, remainder about 12-13m. This is a challenge obJect to 4 Harvard 20 Open Cluster Sagitta 7.7m integrated 6' 162 64 +18°19'12" improve your observation skills. Can you locate the miniature coathanger close by at 19h 37m 27s +19d? Constellation star Corona 5 Corona Borealis 55 Trace the 7 stars making up this constellation, observe and list the colors of each star asterism Borealis 15H 32' 55” Theta Corona Borealis Double Star 4.2m 6.6m .97” 55 Theta requires about 200x +31° 21' 32” The direction our Sun travels in our galaxy. -

SAC's 110 Best of the NGC

SAC's 110 Best of the NGC by Paul Dickson Version: 1.4 | March 26, 1997 Copyright °c 1996, by Paul Dickson. All rights reserved If you purchased this book from Paul Dickson directly, please ignore this form. I already have most of this information. Why Should You Register This Book? Please register your copy of this book. I have done two book, SAC's 110 Best of the NGC and the Messier Logbook. In the works for late 1997 is a four volume set for the Herschel 400. q I am a beginner and I bought this book to get start with deep-sky observing. q I am an intermediate observer. I bought this book to observe these objects again. q I am an advance observer. I bought this book to add to my collect and/or re-observe these objects again. The book I'm registering is: q SAC's 110 Best of the NGC q Messier Logbook q I would like to purchase a copy of Herschel 400 book when it becomes available. Club Name: __________________________________________ Your Name: __________________________________________ Address: ____________________________________________ City: __________________ State: ____ Zip Code: _________ Mail this to: or E-mail it to: Paul Dickson 7714 N 36th Ave [email protected] Phoenix, AZ 85051-6401 After Observing the Messier Catalog, Try this Observing List: SAC's 110 Best of the NGC [email protected] http://www.seds.org/pub/info/newsletters/sacnews/html/sac.110.best.ngc.html SAC's 110 Best of the NGC is an observing list of some of the best objects after those in the Messier Catalog.