Wiki As Pattern Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patterns Senior Member of Technical Staff and Pattern Languages Knowledge Systems Corp

Kyle Brown An Introduction to Patterns Senior Member of Technical Staff and Pattern Languages Knowledge Systems Corp. 4001 Weston Parkway CSC591O Cary, North Carolina 27513-2303 April 7-9, 1997 919-481-4000 Raleigh, NC [email protected] http://www.ksccary.com Copyright (C) 1996, Kyle Brown, Bobby Woolf, and 1 2 Knowledge Systems Corp. All rights reserved. Overview Bobby Woolf Senior Member of Technical Staff O Patterns Knowledge Systems Corp. O Software Patterns 4001 Weston Parkway O Design Patterns Cary, North Carolina 27513-2303 O Architectural Patterns 919-481-4000 O Pattern Catalogs [email protected] O Pattern Languages http://www.ksccary.com 3 4 Patterns -- Why? Patterns -- Why? !@#$ O Learning software development is hard » Lots of new concepts O Must be some way to » Hard to distinguish good communicate better ideas from bad ones » Allow us to concentrate O Languages and on the problem frameworks are very O Patterns can provide the complex answer » Too much to explain » Much of their structure is incidental to our problem 5 6 Patterns -- What? Patterns -- Parts O Patterns are made up of four main parts O What is a pattern? » Title -- the name of the pattern » A solution to a problem in a context » Problem -- a statement of what the pattern solves » A structured way of representing design » Context -- a discussion of the constraints and information in prose and diagrams forces on the problem »A way of communicating design information from an expert to a novice » Solution -- a description of how to solve the problem » Generative: -

Wiki As Pattern Language

Wiki as Pattern Language Ward Cunningham Cunningham and Cunningham, Inc.1 Sustasis Foundation Portland, Oregon Michael W. Mehaffy Faculty of Architecture Delft University of Technology2 Sustasis Foundation Portland, Oregon Abstract We describe the origin of wiki technology, which has become widely influential, and its relationship to the development of pattern languages in software. We show here how the relationship is deeper than previously understood, opening up the possibility of expanded capability for wikis, including a new generation of “federated” wiki. [NOTE TO REVIEWERS: This paper is part first-person history and part theory. The history is given by one of the participants, an original developer of wiki and co-developer of pattern language. The theory points toward future potential of pattern language within a federated, peer-to-peer framework.] 1. Introduction Wiki is today widely established as a kind of website that allows users to quickly and easily share, modify and improve information collaboratively (Leuf and Cunningham, 2001). It is described on Wikipedia – perhaps its best known example – as “a website which allows its users to add, modify, or delete its content via a web browser usually using a simplified markup language or a rich-text editor” (Wikipedia, 2013). Wiki is so well established, in fact, that a Google search engine result for the term displays approximately 1.25 billion page “hits”, or pages on the World Wide Web that include this term somewhere within their text (Google, 2013a). Along with this growth, the definition of what constitutes a “wiki” has broadened since its introduction in 1995. Consider the example of WikiLeaks, where editable content would defeat the purpose of the site. -

Analysis Patterns.Pdf

Symbols for mappings DLKING , : www.dlking.com Generalization notation DLKING , : www.dlking.com Contents Foreword v Foreword vii Preface xv Chapter 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Conceptual Models 1 1.2 The World of Patterns 4 1.3 The Patterns in this Book 8 1.4 Conceptual Models and Business Process Reengineering 10 1.5 Patterns and Frameworks 11 1.6 Using the Patterns 11 References 14 Part 1. Analysis Patterns 15 Chapter 2. Accountability 17 2.1 Party 18 2.2 Organization Hierarchies 19 2.3 Organization Structure 21 2.4 Accountability 22 2.5 Accountability Knowledge Level 24 2.6 Party Type Generalizations 27 2.7 Hierarchic Accountability 28 2.8 Operating Scopes 30 2.9 Post 32 References 33 Chapter 3. Observations and Measurements 35 3.1 Quantity 36 3.2 Conversion Ratio 38 3.3 Compound Units 39 3.4 Measurement 41 3.5 Observation 42 3.6 Subtyping Observation Concepts 46 3.7 Protocol 46 3.8 Dual Time Record 47 IX DLKING , : www.dlking.com x Contents 3.9 Rejected Observation 48 3.10 Active Observation, Hypothesis, and Projection 49 3.11 Associated Observation 50 3.12 Process of Observation 51 References 55 Chapter 4. Observations for Corporate Finance 57 4.1 Enterprise Segment 59 4.2 Measurement Protocol 65 4.3 Range 76 4.4 Phenomenon with Range 77 4.5 Using the Resulting Framework 82 References 83 Chapter 5. Referring to Objects 85 5.1 Name 86 5.2 Identification Scheme 88 5.3 Object Merge 90 5.4 Object Equivalence 92 References 93 Chapter 6. -

Pedagogical and Elementary Patterns Patterns Overview

Pedagogical and Elementary Patterns Overview Patterns Joe Bergin Pace University http://csis.pace.edu/~bergin Thanks to Eugene Wallingford for some material here. Jim (Cope) Coplien also gave advice in the design. 11/26/00 1 11/26/00 2 Patterns--What they DO Where Patterns Came From • Capture Expert Practice • Christopher Alexander --A Pattern Language • Communicate Expertise to Others – Architecture • Solve Common Recurring Problems • Structural Relationships that recur in good spaces • Ward Cunningham, Kent Beck (oopsla ‘87), • Vocabulary of Solutions. Dick Gabriel, Jim Coplien, and others • Bring a set of forces/constraints into • Johnson, Gamma, Helm, and Vlisides (GOF) equilibrium • Structural Relationships that recur in good programs • Work with other patterns 11/26/00 3 11/26/00 4 Patterns Branch Out Patterns--What they ARE • Software Design Patterns (GOF...) •A Thing • Organizational Patterns (XP, SCRUM...) • A Description of a Thing • Telecommunication Patterns (Hub…) • A Description of how to Create the Thing • Pedagogical Patterns •A Solution of a Recurring Problem in a • Elementary Patterns Context – Unfortunately this “definition” is only useful if you already know what patterns are 11/26/00 5 11/26/00 6 Patterns--What they ARE (2) Elements of a Pattern • Structural relationships between •Problem components of a system that brings into • Context equilibrium a set of demands on the system •Forces • A way to generate complex (emergent) •Solution behavior from simple rules • Examples of Use (several) • A way to make the world a better place for humans -- not just developers or teachers... • Consequences and Resulting Context 11/26/00 7 11/26/00 8 Exercise Exercise • Problem: Build a stairway up a castle tower • Problem: Design the intersection of two or • Context: 12th Century Denmark. -

Frontiers of Pattern Language Technology

Frontiers of Pattern Language Technology Pattern Language, 1977 Network of Relationships “We need a web way of thinking.” - Jane Jacobs Herbert Simon, 1962 “The Architecture of Complexity” - nearly decomposable hierarchies (with “panarchic” connections - Holling) Christopher Alexander, 1964-5 “A city is not a tree” – its “overlaps” create clusters, or “patterns,” that can be manipulated more easily (related to Object-Oriented Programming) The surprising existing benefits of Pattern Language technology.... * “Design patterns” used as a widespread computer programming system (Mac OS, iPhone, most games, etc.) * Wiki invented by Ward Cunningham as a direct outgrowth * Direct lineage to Agile, Scrum, Extreme Programming * Pattern languages used in many other fields …. So why have they not been more infuential in the built environment??? Why have pattern languages not been more infuential in the built environment?.... * Theory 1: “Architects are just weird!” (Preference for “starchitecure,” extravagant objects, etc.) * Theory 2: The original book is too “proprietary,” not “open source” enough for extensive development and refinement * Theory 3: The software people, especially, used key strategies to make pattern languages far more useful, leading to an explosion of useful new tools and approaches …. So what can we learn from them??? * Portland, OR. Based NGO with international network of researchers * Executive director is Michael Mehaffy, student and long-time colleague of Christopher Alexander, inter-disciplinary collaborator in philosophy, sciences, public affairs, business and economics, architecture, planning * Board member is Ward Cunningham, one of the pioneers of pattern languages in software, Agile, Scrum etc., and inventor of wiki * Other board members are architects, financial experts, former students of Alexander Custom “Project Pattern Languages” (in conventional paper format) Custom “Project Pattern Languages” create the elements of a “generative code” (e.g. -

Assessing Alexander's Later Contributions to a Science of Cities

Review Assessing Alexander’s Later Contributions to a Science of Cities Michael W. Mehaffy KTH Royal Institute of Technology, 114 28 Stockholm, Sweden; mmehaff[email protected] or michael.mehaff[email protected] Received: 23 April 2019; Accepted: 28 May 2019; Published: 30 May 2019 Abstract: Christopher Alexander published his longest and arguably most philosophical work, The Nature of Order, beginning in 2003. Early criticism assessed that text to be a speculative failure; at best, unrelated to Alexander’s earlier, mathematically grounded work. On the contrary, this review presents evidence that the newer work was a logically consistent culmination of a lifelong and remarkably useful inquiry into part-whole relations—an ancient but still-relevant and even urgent topic of design, architecture, urbanism, and science. Further evidence demonstrates that Alexander’s practical contributions are remarkably prodigious beyond architecture, in fields as diverse as computer science, biology and organization theory, and that these contributions continue today. This review assesses the potential for more particular contributions to the urban professions from the later work, and specifically, to an emerging “science of cities.” It examines the practical, as well as philosophical contributions of Alexander’s proposed tools and methodologies for the design process, considering both their quantitative and qualitative aspects, and their potential compatibility with other tools and strategies now emerging from the science of cities. Finally, it highlights Alexander’s challenge to an architecture profession that seems increasingly isolated, mired in abstraction, and incapable of effectively responding to larger technological and philosophical challenges. Keywords: Christopher Alexander; The Nature of Order; pattern language; structure-preserving transformations; science of cities 1. -

Programming Design Patterns

Programming Design Patterns Patterns for High Performance Computing Marc Snir/Tim Mattson Feb 2006 Dagstuhl Marc Snir Design Pattern High quality solution to frequently recurring problem in some domain Each pattern has a name, providing a vocabulary for discussing the solutions Written in prescribed format to allow the reader to quickly understand the solution and its context 2 Dagstuhl Feb 2006 Marc Snir History ‘60s and ‘70s Berkeley architecture professor Christopher Alexander 253 patterns for city planning, landscaping, and architecture Attempted to capture principles for “living” design. Published in 1977 3 Dagstuhl Feb 2006 Marc Snir Patterns in Object-oriented Programming OOPSLA’87 Kent Beck and Ward Cunningham Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software By the “Gang of Four (GOF)”: Gamma, Helm, Johnson, Vlissides Catalog of patterns Creation, structural, behavioral Published in 1995 4 Dagstuhl Feb 2006 Marc Snir Impact of GOF book Good solutions to frequently recurring problems Pattern catalog Significant influence on object-oriented programming! Created a new vocabulary for software designers. 5 Dagstuhl Feb 2006 Marc Snir The Task Parallelism Pattern Problem: How do you exploit concurrency expressed in terms of a set of distinct tasks? Forces Size of task – small size to balance load vs. large size to reduce scheduling overhead Managing dependencies without destroying efficiency. Solution Schedule tasks for execution with balanced load – use master worker, loop parallelism, or SPMD patterns. Manage dependencies by: removing them (replicating data), transforming induction variables, exposing reductions explicitly protecting (shared data pattern). Intrusion of shared memory model… 6 Dagstuhl Feb 2006 Marc Snir Pattern Languages: A new approach to design Not just a collection of patterns, but a pattern language: Patterns lead to other patterns creating a design as a network of patterns. -

Design Patterns Past and Future

Proceedings of Informing Science & IT Education Conference (InSITE) 2011 Design Patterns Past and Future Aleksandar Bulajic Metropolitan University, Belgrade, Serbia [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract A very important part of the software development process is service or component internal de- sign and implementation. Design Patterns (Gamma et al., 1995) provide list of the common pat- terns used in the object-oriented software design process. The primary goal of the Design Patterns is to reuse good practice in the design of new developed components or applications. Another important reason of using Design Patterns is improving common application design understand- ing and reducing communication overhead by reusing the same generic names for implemented solution. Patterns are designed to capture best practice in a specific domain. A pattern is supposed to present a problem and a solution that is supported by an example. It is always worth to listen to an expert advice, but keep in mind that common sense should decide about particular implemen- tation, even in case when are used already proven Design Patterns. Critical view and frequent and well designed testing would give an answer about design validity and a quality. Design Patterns are templates and cannot be blindly copied. Each design pattern records design idea and shall be adapted to particular implementation. Using time to research and analyze existing solutions is recommendation supported by large number of experts and authorities and fits very well in the pattern basic philosophy; reuse solution that you know has been successfully implemented in the past. Sections 2 and 3 are dedicated to the Design Patterns history and theory as well as literature sur- vey. -

An Introduction to Dependency Inversion Page 1 of 12

Peruse Muse Infuse: An Introduction to Dependency Inversion Page 1 of 12 An Introduction to Dependency Inversion Originaly posted by AdrianK, 1-Nov-2010 at: http://www.morphological.geek.nz/blogs/viewpost/Peruse Muse Infuse/An Introduction to Dependency Inversion.aspx Tagged under: Architecture, Web Development, Patterns An Introduction to Dependency Inversion This article is for anyone (mainly developers, and specifically .Net developers) who is unfamiliar with Dependency Inversion or design patterns in general. The basic rationale behind the Dependency Inversion Principle [1] (DIP, or simply DI) is very simple; and like most other simple design principles it is suitable in many different situations. Once you understand it you’ll wonder how you managed without it. The key benefit it brings is control over dependencies – by removing them (or perhaps more correctly – by “inverting” them), and this isn’t just limited to “code” – you’ll find this also opens up new opportunities regarding how you can structure and run the actual development process. Implementing DI and is fairly straight forward and will often involve other design patterns, such as the Factory pattern [2] and Lazy Load pattern [3] ; and embodies several other principles including the Stable Abstractions Principle and Interface Segregation Principle. I’ll be using acronyms where I can, here’s a quick glossary for them. • BL: Business Logic, sometimes referred to as the Business Logic Layer. • DA: Data Access, often referred to as the DAL or Data Access Layer. • DI: can refer to either Dependency Inversion or Dependency Injection – both of which (at least for this article) essentially mean the same thing. -

Strengthening the Case for Pair Programming

focusprocess diversity Strengthening the Case for Pair Programming The software Laurie Williams, North Carolina State University industry has Robert R. Kessler, University of Utah practiced pair programming—two Ward Cunningham, Cunningham & Cunningham programmers Ron Jeffries working side by side at one or years, programmers in industry have claimed that by working computer on the collaboratively, they have produced higher-quality software prod- same problem— ucts in shorter amounts of time. But their evidence was anecdotal with great success and subjective: “It works” or “It feels right.” To validate these for years. But F people who haven’t claims, we have gathered quantitative evidence showing that pair program- tried it often reject ming—two programmers working side by side at one computer on the same the idea as a waste of resources. The authors design, algorithm, code, or test—does in- programming skill from novice to expert. deed improve software quality and reduce demonstrate that time to market. Additionally, student and Earlier Observations using pair professional programmers consistently find In 1998, Temple University professor programming in pair programming more enjoyable than John Nosek reported on his study of 15 the software working alone. full-time, experienced programmers work- development Yet most who have not tried and tested ing for a maximum of 45 minutes on a chal- process yields pair programming reject the idea as a re- lenging problem important to their organi- dundant, wasteful use of programming re- zation. In their own environments and with better products in sources: “Why would I put two people on a their own equipment, five worked individu- less time—and job that just one can do? I can’t afford to do ally and 10 worked collaboratively in five happier, that!” But we have found, as Larry Con- pairs. -

Understanding Wikis: from Ward’S Brain to Your Browser

06_043998 ch01.qxp 6/19/07 8:20 PM Page 9 Chapter 1 Understanding Wikis: From Ward’s Brain to Your Browser In This Chapter ᮣ Finding your way to wikis ᮣ Understanding what makes a wiki a wiki ᮣ Comparing wikis with blogs and other Web sites ᮣ Examining the history and future of wikis ᮣ How to start using wikis hen Ward Cunningham started programming the first wiki engine Win 1994 and then released it on the Internet in 1995, he set forth a simple set of rules for creating Web sites that pushed all the technical gob- bledygook into the background and made creating and sharing content as easy as possible. Ward’s vision was simple: Create the simplest possible online database that could work. And his attitude was generous; he put the idea out there to let the world run with it. The results were incredible. Ward’s inventiveness and leadership had been long established by the role he played in senior engi- neering jobs, promoting design patterns, and helping develop the concept of Extreme Programming. That a novel idea like the wiki flowed from his mind onto the COPYRIGHTEDInternet was no surprise to those MATERIAL who knew him. The wiki concept turned out to have amazing properties. When content is in a shared space and is easy to create and connect, it can be collectively owned. The community of owners can range from just a few people up into the thousands, as in the case of the online wiki encyclopedia, Wikipedia. 06_043998 ch01.qxp 6/19/07 8:20 PM Page 10 10 Part I: Introducing Wikis This chapter introduces you to the wonderful world of wikis by showing you what a wiki is (or can be), how to find and use wikis for fun and profit, and how to get started with a wiki of your own. -

Ch01: Introduction to Design Patterns

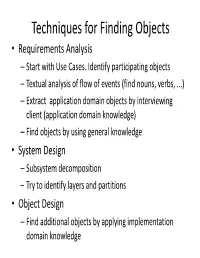

Techniques for Finding Objects • Requirements Analysis – Start with Use Cases. Identify participating objects – TtTextua l analilysis of flow of events (fin d nouns, verbs, ...) – Extract application domain objects by interviewing client (application domain knowledge) – Find objects by using general knowledge • System DiDesign – Subsystem decomposition – Try to identify layers and partitions • Object Design – Find additional objects by applying implementation domain knowledge Another Source for Finding Objects : Design Patterns • What are Design Patterns? – A design pattern describes a problem which occurs over and over again in a software development environment – Then it describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use the this solution many times over, without ever didoing it the same twice – Design patterns are more general than generics Design Patterns encourage reusable Designs • A facade pattern should be used by all subsystems in a software system. – The facade will delegate requests to the appropriate components within the subsystem. Most of the time the façade does not need to be changed, when the component is changed. • Adapters should be used to interface to existing components. – For example, a smart card software system should provide an adapter for a particular smart card reader and other hardware that it controls and queries. • Bridges should be used to interface to a set of objects – where the full set is not completely known at design time. – when the subsystem must be extended later