Music in the Big Apple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Retrospective of Preservation Practice and the New York City Subway System

Under the Big Apple: a Retrospective of Preservation Practice and the New York City Subway System by Emma Marie Waterloo This thesis/dissertation document has been electronically approved by the following individuals: Tomlan,Michael Andrew (Chairperson) Chusid,Jeffrey M. (Minor Member) UNDER THE BIG APPLE: A RETROSPECTIVE OF PRESERVATION PRACTICE AND THE NEW YORK CITY SUBWAY SYSTEM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Emma Marie Waterloo August 2010 © 2010 Emma Marie Waterloo ABSTRACT The New York City Subway system is one of the most iconic, most extensive, and most influential train networks in America. In operation for over 100 years, this engineering marvel dictated development patterns in upper Manhattan, Brooklyn, and the Bronx. The interior station designs of the different lines chronicle the changing architectural fashion of the aboveground world from the turn of the century through the 1940s. Many prominent architects have designed the stations over the years, including the earliest stations by Heins and LaFarge. However, the conversation about preservation surrounding the historic resource has only begun in earnest in the past twenty years. It is the system’s very heritage that creates its preservation controversies. After World War II, the rapid transit system suffered from several decades of neglect and deferred maintenance as ridership fell and violent crime rose. At the height of the subway’s degradation in 1979, the decision to celebrate the seventy-fifth anniversary of the opening of the subway with a local landmark designation was unusual. -

Bonin Responds to Chain of Palisadian Break-Ins

Palisadian-Post Serving the Community Since 1928 22 Pages Thursday, January 10, 2019 ◆ Pacific Palisades, California $1.50 2019 P-A-L-I B-E-E Bonin Responds to Chain Star spellers in first through fifth grade who live or attend of Palisadian Break-Ins school in Pacific Palisades are By JAMES GAGE invited to join the fun for the Reporter 2019 Pali Bee, hosted by the acific Palisades was more bed- Palisadian-Post on Sunday, Plam than Bethlehem this holi- February 10. For more in- day season as a string of burglaries, package thefts and car break-ins formation or to sign up, visit swept across town from Marquez palipost.com/palibee2019. Knolls to the Alphabet Streets, and Suspects caught on camera Rich Schmitt/Staff Photographer from The Huntington to The Riv- iera. and gloves—smashed glass sliding been my focus, and as a result of First reported in the January 3 windows and door panels at six sep- my efforts, LAPD Chief Moore will edition of the Palisadian-Post, a arate residences, stealing jewelry, be deploying 200 more officers to string of four burglaries occurred cash and other incidentals, includ- patrol duty later this month. That’s Palisades-Grown Women in Via Mesa on December 19, fol- ing an airsoft gun. in addition to the 378 officers re- lowed by a theft on the 500 block “The physical description of deployed to neighborhood patrols of Los Liones Drive and a burglary the subject was identical,” said one last year, dozens of which were as- on Napoli Drive in The Riviera on of the victims of the January 2018 signed to the Westside. -

Alexander Glazunov

Call & Response 2011 Music With Exotic Influences Glazunov, Schulhoff, Bloch, Debussy & Jeffery Cotton Listener’s Guide Join us for a performance of music inspired by the Exotic Call & Response 2011 Concert May 5, 2011, Herbst Theatre, San Francisco Details inside… Call & Response 2011: Music with exotic influences Concert Thursday, May 5, 2011 Herbst Theatre at the San Francisco War Memorial 401 Van Ness Avenue at McAllister Street San Francisco, CA 7:15pm Pre-Performance Lecture by composer Jeffery Cotton 8:00pm Performance Buy tickets online at: www.cityboxoffice .com or by calling City Box Office: 415-392-4400 Page Contents 3 The Concept: evolution of music over time and across cultures 4 Jeffery Cotton 6 Alexander Glazunov 8 Erwin Schulhoff 10 Ernest Bloch 12 Claude Debussy 2 Call & Response: The Concept Have you ever wondered how composers, modern composers at that, come up with their ideas? How do composers and other artists create new work? Our Call & Response program was born out of the Cypress String Quartet’s commitment to sharing with you and your community this process in music and all kinds of other artwork. We present newly created music based on earlier composed pieces. Why “Call & Response”? We usually associate the term “call & response” with jazz and gospel music, the idea being that the musician plays a musical “call” to which another musician “responds,”—a way of creating a new sound relating in some way to the original. In this program, the “call” is that of Cypress String Quartet searching for connections across musical, historical, and social boundaries. -

Ziering-Conlon Initiative for Recovered Voices Showcase and Competition Spring 2019

Ziering-Conlon Initiative for Recovered Voices Showcase and Competition Spring 2019 The competition is open to all Colburn School students enrolled for the Spring 2019 semester in the Conservatory, Music Academy, and Community School of Performing Arts. Divisions Prizes Pre-college (Music Academy and Community All finalists will receive a cash award (minimum School) $150 for each student). Solo musicians or College (Conservatory) members of a group judged by the adjudicating panel to be the most outstanding in the pre- Accompanists college and college divisions will receive a Pre-college entrants performing solo repertoire minimum of $1,500 each. with piano may engage a professional accompanist. Pianists in chamber ensembles About the Initiative must be students. All college entrants must LA Opera Music Director James Conlon formed be students in the Conservatory (this includes the groundbreaking Recovered Voices project collaborating pianists). to shine a spotlight on the music by composers suppressed by the Nazi regime. In honor of Deadline his efforts, the Ziering-Conlon Initiative for Entries to be submitted no later than March Recovered Voices sponsors seminars, academic 11, 2019 via YouTube video. Those selected conferences, and competitions in an effort to for the live, public finals on Monday evening, present a deeper understanding of the history March 25, will be notified no later than 9 pm of the music from the first half of the 20th on Tuesday, March 19. All entrants must be century. available to perform at the March 25 finals. Ziering-Conlon Initiative for Recovered Voices Showcase and Competition Spring 2019 List of Repertoire Submitting Your Video Performance The works on the provided list were selected When recording your performances, place as representative, and all are approved for this the video-recording device in such a way that showcase competition. -

Comp. 09 Program Layout.Cwk

T h i r t y - S e c o n d S e a s o n 2 0 0 9 - 2 0 1 0 Celebrating Lukas Tuesday, March 2, 2010, 7:30 p.m. Free admission Alea III celebrates the life and work of Lukas Foss, a great master, with an evening devoted exclusively to his music. ALEA III Echoi For Toru Elegy for Anne Frank For Aaron Plus Theodore Antoniou, Eighteen Epigrams Music Director a new work written by Lukas Foss’s students: Apostolos Paraskevas, Panos Liaropoulos, Michalis Economou, Jakov Jakoulov, Contemporary Music Ensemble Mark Berger, Frank Wallace, Ronald G. Vigue, Julian Wachner, Jeremy Van Buskirk, in residence at Mauricio Pauly, Matt Van Brink, Ivana Lisak, Ramon Castillo, Pedro Malpica, Boston University Paul Vash, Po-Chun Wang, Margaret McAllister, Sunggone Hwang. Theodore Antoniou, conductor Saxes and Horns Wednesday, April 28, 2010, 7:30 p.m. Free admission 27th International Composition Works of unusual instrumentation, featuring 18 saxophones Competition and 9 French horns. Pierre Boulez Dialogue de l’ombre double Theodore Antoniou Music for Nine Gunther Schuller Perpetuum Mobile Sofia Gubaidulina Duo TSAI Performance Center Georgia Spiropoulos Rotations October 4, 2009, 7:00 pm Eric Hewitt la grenouille Eric Ruske, horn, Tsuyoshi Honjo, Eric Hewitt and Jared Sims, saxophones Special guest: Radnofsky Saxophone Ensemble Eric Hewitt, conductor Sponsored by Boston University and the George Demeter Realty. BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOARD OF ADVISORS OUR NEXT ALEA EVENTS President George Demeter Mario Davidovsky Hans Werner Henze Generations Chairman Milko Kelemen André de Quadros Oliver Knussen Monday, November 16, 2009, 7:30 p.m. -

Read the Westchester Guardian

PRESORTED STANDARD PERMIT #3036 WHITE PLAINS NY Vol. VII, No. III Thursday, January 16, 2014 $1.00 Westchester’s Most Influential Weekly SHERIF AWAD Ana Ana Page 5 Political PEGGY GODFREY Resolving to Help New Rochelle Youth Predictions Page 8 ROBERT SCOTT Looking at the Stars in Westchester for New Page 9 LUKE HAMILTON No Justice, Year No Peace Page 11 JOHN F. McMULLEN By Hon. RICHARD BRODSKY, The Odyssey Continues Page 3 (Concludes?) Page 12 JOHN SIMON Back From London COURTS PETITION Page 13 NYS Supreme Court Justice The Super Bowl Smith Favorably Ruled BOB MARRONE Weekend: Making It King Henry II, Jaba the for Yonkers Firefighters Hut, Gov. Chris Christie Local 628 with Respect Even Better Page 16 to General Municipal Law Creating the All-American LEE H. HAMILTON 207-a Procedure Holiday Weekend Trust… But Definitely By HEZI ARIS, Page 3 By GLENN SLABY, Page 4 Verify Page 17 WWW.WESTCHESTERGUARDIAN.COM Page 26 THE WESTCHESTER GUARDIAN THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 2012 CLASSIFIED ADS LEGAL NOTICES Office Space Available- FAMILY COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Prime Location, Yorktown Heights COUNTY OF WESTCHESTER 1,000 Sq. Ft.: $1800. Contact Wilca: 914.632.1230 In the Matter of ORDER TO SHOW CAUSE SUMMONS AND INQUEST NOTICE Prime Retail - Westchester County Chelsea Thomas (d.o.b. 7/14/94), Best Location in Yorktown Heights A Child Under 21 Years of Age Dkt Nos. NN-10514/15/16-10/12C 1100 Sq. Ft. Store $3100; 1266 Sq. Ft. store $2800 and 450 Sq. Ft. Store $1200. Adjudicated to be Neglected by NN-2695/96-10/12B Suitable for any type of business. -

The Lighthouse Peddler Features Another Bird Regularly Seen at Or Near the Mendonoma Coast

ALWAYS FREE Lighthouse January 2020 Peddler The Guide To Music, Events, Theater, Film, Art, Poetry, and Life on the Mendocino Coast BAKU A Special Global Harmony Winter Concert At Gualala Arts. January 26. BAKU, the popular Mendonoman World-Fu- pulse. Baku’s self-styled musical hybrid,”Jambient sion ensemble will return to Gualala Arts Cen- Soundscapes,” is a fusion of jazz and Afro beat, ter’s for a performance on Sunday, January 26, at drawing upon Cuban, Latin, Middle Eastern and 4:00pm for an intimate concert. Tickets are $15 other world cultural infuences and rhythms. advance, $20 if purchased the day of the concert Te members of the group are a uniqely talent- and are available online at BrownPaperTickets, ed group of musicians. BAKU includes Harrison and locally at Gualala Arts Center and Dolphin Goldberg, saxophones and percussion, Chris Gallery. Doering, 7-string guitar and synthesizer, Tim Tis will be a special Global Harmony Win- Mueller, 6-string guitar and guitar synthesizer, ter concert in the intimate surroundings of the David French, upright bass and percussion and Elaine Jacob Foyer. Te band will showcase its Nancy Feehan, cajon and percussion. distinctive and captivating improvised sounds BAKU was selected as the name of the group to that combine contemplative, ambient structures honor . and melodies with a strong yet relaxing rhythmic Cont’d on page 17 “Diamond In The Rough” Anchor Bay Village vintage mobile home on 11.93 acres: redwood forest, blue water views, located above & wrapping around top of Anchor Bay Sub. All utilities @ mobile home on 1st terrace; primary building site on 2nd tier has primary utility hook-ups and is located in the middle of the parcel which extends to the creek on the southern side of the utility access road. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

MITCHELL, MARGARET. Margaret Mitchell Collection, 1922-1991

MITCHELL, MARGARET. Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Mitchell, Margaret. Title: Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 265 Extent: 3.75 linear feet (8 boxes), 1 oversized papers box and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), and AV Masters: .5 linear feet (1 box, 1 film, 1 CLP) Abstract: Papers of Gone With the Wind author Margaret Mitchell including correspondence, photographs, audio-visual materials, printed material, and memorabilia. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction Special restrictions apply: Requests to publish original Mitchell material should be directed to: GWTW Literary Rights, Two Piedmont Center, Suite 315, 3565 Piedmont Road, NE, Atlanta, GA 30305. Related Materials in Other Repositories Margeret Mitchell family papers, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia and Margaret Mitchell collection, Special Collections Department, Atlanta-Fulton County Public Library. Source Various sources. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. Margaret Mitchell collection, 1922-1991 Manuscript Collection No. -

Scambi Fushi Tarazu: a Musical Representation of a Drosophila Gene Expression Pattern

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 4 January 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202001.0026.v1 Scambi fushi tarazu: A Musical Representation of a Drosophila Gene Expression Pattern Derek Gatherer Division of Biomedical & Life Sciences Lancaster University Lancaster LA1 4YW, UK [email protected] Abstract: The term Bio-Art has entered common usage to describe the interaction between the arts and the biological sciences. Although Bio-Art implies that Bio-Music would be one of its obvious sub- disciplines, the latter term has been much less frequently used. Nevertheless, there has been no shortage of projects that have brought together music and the biological sciences. Most of these projects have allowed the biological data to dictate to a large extent the sound produced, for instance the translation of genome or protein sequences into musical phrases, and therefore may be regarded as process compositions. Here I describe a Bio-Music process composition that derives its biological input from a visual representation of the expression pattern of the gene fushi tarazu in the Drosophila embryo. An equivalent pattern is constructed from the Scambi portfolio of short electronic music fragments created by Henri Pousseur in the 1950s. This general form of the resulting electronic composition follows that of the fushi tarazu pattern, while satisfying the rules of the Scambi compositional framework devised by Pousseur. The range and flexibility of Scambi make it ideally suited to other Bio-Music projects wherever there is a requirement, or desire, to build larger sonic structures from small units. Keywords: Scambi; fushi tarazu; Drosophila; BioArt; BioMusic; Music; process composition 1 © 2020 by the author(s). -

Lost Generation.” Two Recent Del Sol Quartet Recordings Focus on Their Little-Known Chamber Music

American Masterpieces Chamber Music Americans in Paris Like Hemingway and Fitzgerald, composers Marc Blitzstein and George Antheil were a part of the 1920s “Lost Generation.” Two recent Del Sol Quartet recordings focus on their little-known chamber music. by James M. Keller “ ou are all a lost generation,” Generation” conveyed the idea that these Gertrude Stein remarked to literary Americans abroad were left to chart Y Ernest Hemingway, who then their own paths without the compasses of turned around and used that sentence as the preceding generation, since the values an epigraph to close his 1926 novel The and expectations that had shaped their Sun Also Rises. upbringings—the rules that governed Later, in his posthumously published their lives—had changed fundamentally memoir, A Moveable Feast, Hemingway through the Great War’s horror. elaborated that Stein had not invented the We are less likely to find the term Lost locution “Lost Generation” but rather merely Generation applied to the American expa- adopted it after a garage proprietor had triate composers of that decade. In fact, used the words to scold an employee who young composers were also very likely to showed insufficient enthusiasm in repairing flee the United States for Europe during the ignition in her Model-T Ford. Not the 1920s and early ’30s, to the extent that withstanding its grease-stained origins, one-way tickets on transatlantic steamers the phrase lingered in the language as a seem to feature in the biographies of most descriptor for the brigade of American art- American composers who came of age at ists who spent time in Europe during the that moment. -

AUG 2016 HITLIST Content Warning COMPILED from MEDIA CHARTS and FEEDBACK the Industry's #1 Source for Music & Music Video

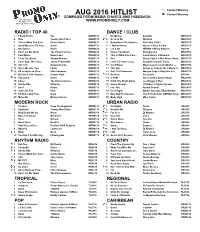

Content Warning AUG 2016 HITLIST Content Warning COMPILED FROM MEDIA CHARTS AND FEEDBACK The Industry's #1 Source For WWW.PROMOONLY.COM Music & Music Video RADIO / TOP 40 DANCE / CLUB 1 Cheap Thrills Sia MSR0416 1 No Money Galantis MSC0816 2 Ride Twenty One Pilots MSR0516 2 Needed Me Rihanna MSC0816 3 This Is What You Cam... Calvin Harris MSR0616 3 Bring Back The Summe... Rain Man f./OLY MSC0716 4 Send My Love (To You... Adele MSR0716 4 I Wanna Know Alesso f./Nico & Vinz MSC0716 5 One Dance Drake MSR0516 5 Let It Go NERVO f./Nicky Romero RC0716 6 Don't Let Me Down The Chainsmokers MSR0416 6 Chase You Down Runaground MSC0516 7 Cold Water Major Lazer MSR0916 7 This Is What You Cam... Calvin Harris f./Rihanna MSC0816 8 Treat You Better Shawn Mendes MSR0716 8 Sex Cheat Codes x Kris Kross Amst... MSC0716 9 Can't Stop The Feeli... Justin Timberlake MSR0616 9 Livin' For Your Love... Rosabel f./Jeanie Tracy MSC0616 10 Into You Ariana Grande MSR0816 10 Cold Water Major Lazer f./Justin Bieber ... MSC0916 11 Never Be Like You Flume MSR0516 11 This Girl Kungs vs Cookin' On 3 Burners MSC0816 12 All In My Head (Flex... Fifth Harmony MSR0716 12 Safe Till Tomorrow Morgan Page f./Angelika Vee MSC0716 13 We Don't Talk Anymor... Charlie Puth MSR0716 13 Bonbon Era Istrefi RC0816 14 Too Good Drake MSR0816 14 ILYSM Steve Aoki & Autoerotique MSC0916 15 Closer The Chainsmokers MSR0916 15 Drink The Night Away Lee Dagger f./Bex MSC0616 16 Needed Me Rihanna MSR0816 16 Sweet Dreams JX Riders f./Skylar Stecker MSC0916 17 Gold Kiiara MSR0716 17 Into You Ariana Grande MSC0816 18 Just Like Fire Pink MSR0816 18 Do It Right Martin Solveig f./Tkay Maidza MSC0816 19 Sit Still, Look Pret..