Foundation Funding and the Creation of U.S. Climate Change Counter-Movement Organizations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S5011

July 12, 2016 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE S5011 The clerk will report the bill by title. COMMENDING THE TENNESSEE experienced its warmest June on record The senior assistant legislative clerk VALLEY AUTHORITY ON THE ever. Already this year there have been read as follows: 80TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE UNI- eight weather-related and climate-re- A bill (S. 2650) to amend the Internal Rev- FIED DEVELOPMENT OF THE lated disasters that each caused at enue Code of 1986 to exclude from gross in- TENNESSEE RIVER SYSTEM least $1 billion in damage. Globally, it come any prizes or awards won in competi- Mr. COTTON. Mr. President, I ask was found that 2015 was the hottest tion in the Olympic Games or the year on record, and so far this year is Paralympic Games. unanimous consent that the Senate proceed to the consideration of S. Res. on track to beat last year. We can’t There being no objection, the Senate 528, submitted earlier today. even hold the record for a year—2016 proceeded to consider the bill. The PRESIDING OFFICER. The has been as hot as Pokemon GO—and Mr. COTTON. Mr. President, I ask clerk will report the resolution by anyone watching the Senate floor to- unanimous consent that the bill be title. night who is younger than 31 has never read a third time and passed, the mo- The senior assistant legislative clerk experienced in their life a month where tion to reconsider be considered made read as follows: the temperature was below the 20th and laid upon the table, and that the century average. -

Accelerated Attacks on Clean Energy by Koch Bros

Checks and Balances Project Documents: Accelerated Attacks on Clean Energy by Koch Bros. $192 Million to 72 Groups Associated with Opposition to Clean Energy Solutions and Climate Change Denial from 1997-2013 $108 Million to At Least 19 Groups to Fight State Renewable Energy Policies 2011-2013 (Over 18 months, Checks and Balances Project conducted the first in-depth investigation into Koch Industries, Inc. AND what we call the Koch Advocacy Network. Over 350 low-profile regulatory disclosures and more than 8,000 legal disclosure forms drawn from over 60 public agencies, databases and courts were examined. Research was completed prior to the 2016 election.) In August 2015 President Obama singled out the “massive lobbying efforts backed by fossil fuel interests, or conservative think tanks, or the Koch brothers pushing for new laws to roll back renewable energy standards or prevent new clean energy businesses from succeeding.” The President described these anti-clean energy efforts as “rent seeking and trying to protect old ways of doing business and standing in the way of the future.”1 Charles Koch responded that, “We are not trying to prevent new clean energy businesses from succeeding” and warned against “subsidizing uneconomical forms of energy — whether you call them ‘green,’ ‘renewable’ or whatever.” He continued, “And there is a big debate on whether you have a real disease or something that’s not that serious. I recognize there is a big debate about that. But whatever it is, the cure is to do things in the marketplace, and to let individuals and companies innovate, to come up with alternatives that will deal with whatever the problem may be in an economical way so we don’t squander resources on uneconomic approaches.” 2 The defense outlined by Charles mirrors the strategy of the network he oversees. -

Threat to Public Education Now Centers on Massachusetts

THREAT TO PUBLIC EDUCATION NOW CENTERS ON MASSACHUSETTS May 2016 Preface This document updates and expands on Threat from the Right, an MTA task force report issued in May 2013. During the intervening years, the threat to public education, organized labor and social justice has grown substantially. Massachusetts is now in the crosshairs, with the forces behind charter schools, privatization and other attacks on the public good coalescing on Beacon Hill and throughout the state. That is reflected in the title of the 2016 edition, Threat to Public Education Now Centers on Massachusetts. No one should doubt the danger of the challenges outlined in these pages or the intensity of the forces behind them, which are national in scope. Nevertheless, winning the many fights we face is well within the power of the MTA and our allies — parents, students and other members of communities across Massachusetts and the nation. Understanding our opponents is an important step, and this report is intended to help us move toward meaningful victories as we continue to organize, mobilize and build the power we need to realize the goals of our Strategic Action Plan. Contents Introduction Elements of the Charter Campaign The Massachusetts Alignment ......................................................................................................7 Great Schools Massachusetts.......................................................................................................9 Families for Excellent Schools ....................................................................................................11 -

Koch Millions Spread Influence Through Nonprofits, Colleges

HOME ABOUT STAFF INVESTIGATIONS ILAB BLOGS WORKSHOP NEWS Koch millions spread influence through nonprofits, colleges B Y C H A R L E S L E W I S , E R I C H O L M B E R G , A L E X I A F E R N A N D E Z C A M P B E L L , LY D I A B E Y O U D Monday, July 1st, 2013 ShareThis Koch Industries, one of the largest privately held corporations in the world and principally owned by billionaires Charles and David Koch, has developed what may be the best funded, multifaceted, public policy, political and educational presence in the nation today. From direct political influence and robust lobbying to nonprofit policy research and advocacy, and even increasingly in academia and the broader public “marketplace of ideas,” this extensive, cross-sector Koch club or network appears to be unprecedented in size, scope and funding. And the relationship between these for-profit and nonprofit entities is often mutually reinforcing to the direct financial and political interests of the behemoth corporation — broadly characterized as deregulation, limited government and free markets. The cumulative cost to Koch Industries and Charles and David Koch for this extraordinary alchemy of political and lobbying influence, nonprofit public policy underwriting and educational institutional support was $134 million over a recent five- year period. The global conglomerate has 60,000 employees and annual revenue of $115 billion and estimated pretax profit margins of 10 percent, according to Forbes. An analysis by the Investigative Reporting Workshop found that from 2007 through 2011, Koch private foundations gave $41.2 million to 89 nonprofit organizations and an annual libertarian conference. -

Monetized Hate: Decoding the Network

MONETIZED HATE: DECODING THE NETWORK THE NETWORK REVISITED The present scourge of anti-Arab and anti-Muslim bigotry in our country is rooted in a calculated, insidious effort to contaminate our public discourse. This effort dates back to the early 2000s, when a small, interlaced network of analysts and activists exploited a nationwide climate of fear in the aftermath of 9/11. To be sure, the systemic mistreatment of our Arab American and American Muslim communities did not begin with the new millennium. However, the success of this so-called network to mainstream hateful rhetoric and advance discriminatory policies is considerable, and thus deserves outsize attention. In 2011, The Center for American Progress (CAP) published “Fear, Inc. The Roots of the Islamophobia Network in America.”1 The report found that a nationwide rise in anti-Muslim bigotry was traceable to a handful of “misinformation experts.” These individuals and their organizations relied on a syndicate of activists, media partners, and grassroots organizing to radiate bias presented as fact. They also relied on significant financial support from a select group of charitable foundations. This network of donors, analysts, and activists not only distorted millions of Americans’ understanding of Islam and Muslims, it also drove inequitable policies. One example highlighted in the report was that of so-called “anti-Sharia bills”2 introduced in numerous state legislatures. Most of these bills drew from model legislation drafted by David Yerushalmi,3 an SPLC-designated anti-Muslim extremist. CAP released a follow-up in 2015 entitled “Fear Inc., 2.0. The Islamophobia Network’s Effects to Manufactured Hate in America.” 4 While the revelations of CAP’s initial report led charitable organizations, politicians, and the media to sever ties with many of the network’s key members, the 2015 edition also found that individuals within the network had successfully advanced a range of anti-Muslim policies at the local, state, and federal level. -

Protecting Donor Privacy Philanthropic Freedom, Anonymity and the First Amendment

Protecting Donor Privacy Philanthropic Freedom, Anonymity and the First Amendment www.PhilanthropyRoundtable.org www.ACReform.org Contents 1 Executive Summary 3 Introduction 3 A Rich Tradition and History of Anonymous Giving 7 A Constitutionally Protected Right 9 Activists and Attorneys General Threaten Donor Privacy 13 Legislators Seek to Undermine Anonymous Giving 14 Is Anonymity Still Needed? 16 Confusing Politics, Government, and Charity 18 Ideology and Donor Privacy 20 Donor Anonymity is Worth Protecting 22 Endnotes Executive Summary among them for supporters of unpopular causes or organizations is the reality that exposure will lead to harassment or threat The right of charitable donors to remain of retribution. anonymous has long been a hallmark of American philanthropy for donors both large Among the more prominent examples is the and small. Donor privacy allows charitable harassment of brothers Charles and David givers to follow their religious teachings, Koch, who have helped fund a broad range insulate themselves from retribution, avoid of nonprofit organizations ranging from unwanted solicitations, and duck unwelcome Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center publicity. It also upholds and protects important to the libertarian-oriented Cato Institute, as First Amendment rights of free speech and well as organizations that engage in political association. However, recent actions by activity. As a result of their giving, the Koch elected officials, activists, and organizations brothers and their companies routinely face are challenging this right and threatening death threats, cyber-attacks from the hacker to undermine private philanthropy’s ability group “Anonymous,” and boycotts aimed at to effectively address some of society’s most the many consumer products their companies challenging issues. -

Threat from the Right Intensifies

THREAT FROM THE RIGHT INTENSIFIES May 2018 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 Meeting the Privatization Players ..............................................................................3 Education Privatization Players .....................................................................................................7 Massachusetts Parents United ...................................................................................................11 Creeping Privatization through Takeover Zone Models .............................................................14 Funding the Privatization Movement ..........................................................................................17 Charter Backers Broaden Support to Embrace Personalized Learning ....................................21 National Donors as Longtime Players in Massachusetts ...........................................................25 The Pioneer Institute ....................................................................................................................29 Profits or Professionals? Tech Products Threaten the Future of Teaching ....... 35 Personalized Profits: The Market Potential of Educational Technology Tools ..........................39 State-Funded Personalized Push in Massachusetts: MAPLE and LearnLaunch ....................40 Who’s Behind the MAPLE/LearnLaunch Collaboration? ...........................................................42 Gates -

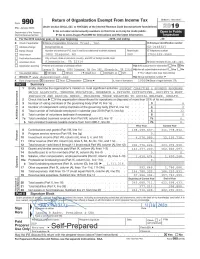

Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check If Schedule O Contains a Response Or Note to Any Line in This Part III

Form 990 (2019) Page 2 Part III Statement of Program Service Accomplishments Check if Schedule O contains a response or note to any line in this Part III . 1 Briefly describe the organization’s mission: SUPPORT CHARITIES & SPONSOR PROGRAMS WHICH ALLEVIATE, THROUGH EDUCATION, RESEARCH & PRIVATE INITIATIVES, SOCIETY'S MOST PERVASIVE AND RADICAL NEEDS, INCLUDING THOSE RELATING TO SOCIAL WELFARE, HEALTH, 2 Did the organization undertake any significant program services during the year which were not listed on the prior Form 990 or 990-EZ? ........................... Yes No If “Yes,” describe these new services on Schedule O. 3 Did the organization cease conducting, or make significant changes in how it conducts, any program services? ................................. Yes No If “Yes,” describe these changes on Schedule O. 4 Describe the organization’s program service accomplishments for each of its three largest program services, as measured by expenses. Section 501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are required to report the amount of grants and allocations to others, the total expenses, and revenue, if any, for each program service reported. 4 a (Code: ) (Expenses $ 163,183,043. including grants of $ 161,930,479. ) (Revenue $0. ) DAF PROGRAM - A DONOR ADVISED FUND (DAF) PROGRAM ALLOWING DAF CONTRIBUTORS TO ADVISE GRANTS THAT SUPPORT CHARITIES WHICH ALLEVIATE, THROUGH EDUCATION, RESEARCH AND PRIVATE INITIATIVES, SOCIETY'S MOST PERVASIVE AND RADICAL NEEDS, INCLUDING THOSE RELATING TO SOCIAL WELFARE, HEALTH, ENVIRONMENT, ECONOMICS, GOVERNANCE, FOREIGN RELATIONS AND ARTS AND CULTURE; AND WHICH ENCOURAGE PRIVATE PHILANTHROPY AND INDIVIDUAL GIVING AND RESPONSIBILITY AS AN ANSWER TO SOCIETY'S NEEDS, AS OPPOSED TO GOVERNMENTAL INVOLVEMENT. -

How Right Wing Funders Are Manufacturing News and Influencing Public Policy in Pennsylvania

Driving the News How right wing funders are manufacturing news and influencing public policy in Pennsylvania A Report by Keystone Progress August, 2013 This report was produced by Keystone Progress. Keystone Progress is Pennsylvania’s largest progressive advocacy organization with over 350,000 subscribers. Keystone Progress embraces a pragmatic and flexible approach to advancing equal opportunity for all, the protection of individual freedoms, and democratic, transparent and people-oriented (rather than corporate) government. We support every worker’s right to organize and earn a living wage, every individual’s right to control their reproductive health options, every child’s right to public education, and every human being’s right to breathe clean air, drink clean water, and access adequate health care, food and shelter. [email protected] 610-990-6300 2 Executive Summary There is a disturbing new movement to supplant genuine investigative reporting with pseudo-reporting by right-wing advocacy organizations. These advocacy groups, posing as legitimate news bureaus, are well funded and have become accepted as objective news organizations by many mainstream newspapers, television and radio news operations. In fact, one such network claims that it is already "provides 10 percent of all daily reporting from state capitals nationwide."i This insidious infiltration of legitimate news operations is led by the Franklin Center for Government and Public Integrity. Its local affiliate in Pennsylvania is the Pennsylvania Independent. Key Findings . Despite its claims, the Pennsylvania Independent is far from being independent or unbiased. The Pennsylvania Independent is run by the far-right Franklin Center for Government and Public Integrity, which has close ties to the American Legislative Exchange Council, the Koch brothers, the Tea Party, the Conservative Political Action Conference, the Heritage Foundation and numerous other conservative causes and candidates. -

EXPOSED:The State Policy Network

EXPOSED: The State Policy Network The Powerful Right-Wing Network Helping to Hijack State Politics and Government CENTER FOR MEDIA AND DEMOCRACY | ALECEXPOSED.ORG November 2013 ©2013 Center for Media and Democracy. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by information exchange and retrieval system, without permission from the authors. Center for Media and Democracy ALECexposed.org | PRWatch.org | SourceWatch.org 520 University Avenue, Suite 260 Madison, WI 53703 | (608) 260-9713 (This publication is available online at ALECexposed.org) CMD, publisher of ALECexposed.org, PRWatch.org, and SourceWatch.org, has created a clearinghouse of information on the State Policy Network at sourcewatch.org/index.php/Portal:State_Policy_Network and a reporter’s guide to SPN at prwatch.org/node/11909/. Please see these online resources for more information. This report was written by Rebekah Wilce, with contributions by Lisa Graves, Mary Bottari, Nick Surgey, Jay Riestenberg, Katie Lorenze, Drew Curtis, and Sari Williams. This report on SPN is also part of a joint effort with Progress Now called www.StinkTanks.org, which includes information about what citizens can do in response to SPN's secretive influence on the state laws that affect their lives. Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................... 1 SPN’s Founding and Role in the National Right-Wing -

US Mainstream Media Index May 2021.Pdf

Mainstream Media Top Investors/Donors/Owners Ownership Type Medium Reach # estimated monthly (ranked by audience size) for ranking purposes 1 Wikipedia Google was the biggest funder in 2020 Non Profit Digital Only In July 2020, there were 1,700,000,000 along with Wojcicki Foundation 5B visitors to Wikipedia. (YouTube) Foundation while the largest BBC reports, via donor to its endowment is Arcadia, a Wikipedia, that the site charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and had on average in 2020, Peter Baldwin. Other major donors 1.7 billion unique visitors include Google.org, Amazon, Musk every month. SimilarWeb Foundation, George Soros, Craig reports over 5B monthly Newmark, Facebook and the late Jim visits for April 2021. Pacha. Wikipedia spends $55M/year on salaries and programs with a total of $112M in expenses in 2020 while all content is user-generated (free). 2 FOX Rupert Murdoch has a controlling Publicly Traded TV/digital site 2.6M in Jan. 2021. 3.6 833,000,000 interest in News Corp. million households – Average weekday prime Rupert Murdoch Executive Chairman, time news audience in News Corp, son Lachlan K. Murdoch, Co- 2020. Website visits in Chairman, News Corp, Executive Dec. 2020: FOX 332M. Chairman & Chief Executive Officer, Fox Source: Adweek and Corporation, Executive Chairman, NOVA Press Gazette. However, Entertainment Group. Fox News is owned unique monthly views by the Fox Corporation, which is owned in are 113M in Dec. 2020. part by the Murdoch Family (39% share). It’s also important to point out that the same person with Fox News ownership, Rupert Murdoch, owns News Corp with the same 39% share, and News Corp owns the New York Post, HarperCollins, and the Wall Street Journal. -

Silver Spoon Oligarchs

CO-AUTHORS Chuck Collins is director of the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies where he coedits Inequality.org. He is author of the new book The Wealth Hoarders: How Billionaires Pay Millions to Hide Trillions. Joe Fitzgerald is a research associate with the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good. Helen Flannery is director of research for the IPS Charity Reform Initiative, a project of the IPS Program on Inequality. She is co-author of a number of IPS reports including Gilded Giving 2020. Omar Ocampo is researcher at the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good and co-author of a number of reports, including Billionaire Bonanza 2020. Sophia Paslaski is a researcher and communications specialist at the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good. Kalena Thomhave is a researcher with the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to thank Sarah Gertler for her cover design and graphics. Thanks to the Forbes Wealth Research Team, led by Kerry Dolan, for their foundational wealth research. And thanks to Jason Cluggish for using his programming skills to help us retrieve private foundation tax data from the IRS. THE INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES The Institute for Policy Studies (www.ips-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center that has been conducting path-breaking research on inequality for more than 20 years. The IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good was founded in 2006 to draw attention to the growing dangers of concentrated wealth and power, and to advocate policies and practices to reverse extreme inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunity.