Westonia Common Conservation Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mining Dump Structures Reference List

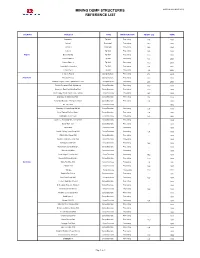

MINING DUMP STRUCTURES UPDATE OCTOBER 2012 REFERENCE LIST COUNTRY PROJECT TYPE MAIN FUNCTION HEIGHT [m] YEAR Luzamba Tip Wall Processing 11,4 1992 Catoca I Dump wall Processing 19,0 1995 Catoca II Dump wall Processing 16,0 1995 Catoca Tip Wall Processing 10,5 1996 Angola Escom Mining Tip Wall Processing 11,0 2002 Catoca Phase 1 Tip Wall Processing 13,6 2006 Catoca Phase 2 Tip Wall Processing 13,0 2006 Jopro 004 – Consulmet Tip Wall Processing 9,0 2007 Consulmet 2 Tip Wall Processing 9,0 2008 Veladero Project Dump structure Processing 27,8 2005 Argentina Pirquitas Project Dump structure Processing 18,0 2009 Veladero Project - Plant Expansion 85 KTPD Dump structure Processing 28,5 2009 Eastern Deepdale Pocket/Abutment Dump Structure Processing 16,0 1980 Saxonvale Raw Coal Handling Plant Dump Structure Processing 12,0 1981 Rom Hopper Walls Pacific Coal - Tarong Dump Structure Processing 19,5 1982 Boundary Hill Inpit Dump Wall - Dump Structure Processing 7,8 1982 Load Out Structure - Kangaroo Island Dump Structure Processing 6,0 1982 Mt. Tom Price Dump Structure - - 1982 Boundary Hill Inpit Dump Wall #2 Dump Structure Processing 8,0 1983 Kress Tipping Platform Stage I Dump Structure Processing 4,9 1984 Paddington Gold Project Dump Structure Processing 14,3 1984 Cork Tree Well Gold Mine Dump Wall Dump Structure Processing - 1985 Dump Wall - Cue Dump Structure Processing 8,3 1986 Telfer Mine Dump Structure Processing - 1986 Howick Colliery Temp Dump Wall Dump Structure Processing 8,4 1986 Wiluna Mine Dump Wall Dump Structure Processing - 1986 -

The Mineral Industry of Australia in 2012

2012 Minerals Yearbook AUSTRALIA U.S. Department of the Interior February 2015 U.S. Geological Survey THE MINERAL INDUSTRY OF AUSTRALIA By Pui-Kwan Tse Australia was subject to volatile weather in recent years Government Policies and Programs that included heavy rains and droughts. The inclement weather conditions affected companies’ abilities to expand The powers of Australia’s Commonwealth Government are their activities, such as port, rail, and road construction and defined in the Australian Constitution; powers not defined in the repair, as well as to mine, process, manufacture, and transport Constitution belong to the States and Territories. Except for the their materials. Slow growth in the economies of the Western Australian Capital Territory (that is, the capital city of Canberra developed countries in 2012 affected economic growth and its environs), all Australian States and Territories have negatively in many counties of the Asia and the Pacific region. identified mineral resources and established mineral industries. China, which was a destination point for many Australian Each State has a mining act and mining regulations that mineral exports, continued to grow its economy in 2012, regulate the ownership of minerals and the operation of mining although the rate of growth was slower than in previous years. activities in that State. The States have other laws that deal with As a result, Australia’s gross domestic product (GDP) increased occupational health and safety, environment, and planning. at a rate of 3.1% during 2012, which was higher than the All minerals in the land are reserved to the Crown; however, 2.3% rate of growth recorded in 2011. -

Split Rocks Cobalt - Nickel Drilling Commenced

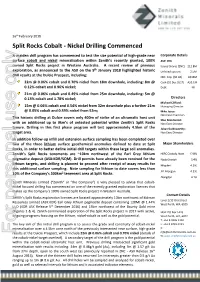

26th February 2018 Split Rocks Cobalt - Nickel Drilling Commenced A maiden drill program has commenced to test the size potential of high-grade near Corporate Details surface cobalt and nickel mineralisation within Zenith’s recently granted, 100% ASX: ZNC owned Split Rocks project in Western Australia. A recent review of previous Issued Shares (ZNC) 212.8M th exploration, as announced to the ASX on the 9 January 2018 highlighted historic Unlisted options 2.5M drill results at the Dulcie Prospect, including: Mkt. Cap. ($0.18) A$36M 22m @ 0.06% cobalt and 0.70% nickel from 18m downhole, including: 8m @ Cash (31 Dec 2017) A$3.1M 0.12% cobalt and 0.96% nickel; Debt Nil 21m @ 0.06% cobalt and 0.49% nickel from 25m downhole, including: 5m @ 0.13% cobalt and 1.78% nickel; Directors Michael Clifford: 15m @ 0.06% cobalt and 0.54% nickel from 32m downhole plus a further 21m Managing Director @ 0.05% cobalt and 0.59% nickel from 52m; Mike Joyce: Non Exec Chairman This historic drilling at Dulcie covers only 400m of strike of an ultramafic host unit Stan Macdonald: with an additional up to 9km’s of untested potential within Zenith’s Split Rocks Non Exec Director tenure. Drilling in this first phase program will test approximately 4.5km of the Julian Goldsworthy: target area. Non Exec Director In addition follow-up infill and extension surface sampling has been completed over two of the three lithium surface geochemical anomalies defined to date at Split Major Shareholders Rocks, in order to better define initial drill targets within these large soil anomalies. -

P5341b-5366A Hon Ken Travers; Deputy President; Hon Norman Moore; Hon Phil Edman; Hon Michael Mischin; President; Hon Mia Davies; Hon Jon Ford

Extract from Hansard [COUNCIL - Tuesday, 23 June 2009] p5341b-5366a Hon Ken Travers; Deputy President; Hon Norman Moore; Hon Phil Edman; Hon Michael Mischin; President; Hon Mia Davies; Hon Jon Ford LOAN BILL 2009 Second Reading Resumed from an earlier stage of the sitting. HON KEN TRAVERS (North Metropolitan) [5.37 pm]: When I commenced my remarks, I said that just about every day that we come into this place we see another example of this budget unravelling and another black hole appearing in the budget. The pace is picking up as it now seems that every time we ask a question we find yet more holes opening in the budget and the financial management of this state by the members opposite. I will go through some of these a little later on in this debate. I will point out how some of the questions in question time highlighted just how out of control the budget process is under this state government and how — Hon Sally Talbot interjected. Hon KEN TRAVERS: Absolutely. I started the debate by pointing out that $20 million had been lost from the environment portfolio through what could only be described as sheer incompetence! In fairness to the Minister for Environment, on this occasion I do not think it was her incompetence that caused this because, as we heard in the estimates hearing last week, the incompetence was that of the faceless men of the committee that imposed this revenue grab on her portfolio. It is my recollection, if I am not mistaken, that the Minister for Environment told everyone that it was imposed on her. -

Ramelius Resources Limited 2018 Annual Report Contents

RAMELIUS RESOURCES LIMITED 2018 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS Chairman’s Report 1 RAMELIUS RESOURCES LIMITED Vale Robert Michael Kennedy 7 ACN 001 717 540 Managing Director’s Report 13 ABN 51 001 717 540 Review of Operations 14 Glossary of Terms 34 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Native Title Statement 39 The Annual General Meeting of Sustainability Statement 40 Ramelius Resources Limited will be held at Diversity Statement 43 Hyatt Regency Perth, Ramelius Board of Directors 45 99 Adelaide Terrace, and Senior Executives Perth WA 6000 Corporate Governance Statement 46 on Thursday 29 November 2018 Annual Financial Report 47 at 11am Perth time. - Directors’ Report 48 - Auditor’s Independence Declaration 64 STOCK EXCHANGE - Income Statement 66 The Company is listed - Statement of Comprehensive Income 67 on the Australian Securities - Balance Sheet 68 Exchange Limited. - Statement of Changes in Equity 69 - Statement of Cash Flows 70 ASX CODE - Notes to the Financial Statements 71 Shares: RMS - Directors’ Declaration 109 - Independent Auditor’s Report 110 Shareholder Information 115 Corporate Directory Back Cover Mt Magnet Mine Camp Front Cover: Edna May Stage 2 Open Pit Mine. CHAIRMAN’S REPORT Dear fellow Shareholders, On behalf of the Board of Directors, I present to you Bob was a Knight of Honour of the Order of St John of the 2018 Annual Report of Ramelius Resources Jerusalem Knights Hospitaller, a service organisation Limited. which raises money for charitable institutions associated with the poor and sick, including Shareholders will be aware that I was appointed the Mary Potter Hospice in North Adelaide where Chairman earlier this year following the passing of ultimately, and very fittingly, he was cared for in his our previous long-standing and founding Chairman, last days. -

Flora and Vegetation Survey for the Edna May Greenfinch Project

Flora and vegetation survey for the Edna May Greenfinch Project Prepared for Evolution Mining Ltd August 2016 Final Report Flora and vegetation survey for the Edna May Greenfinch Project Prepared for Evolution Mining Ltd Flora and vegetation survey for the Edna May Greenfinch Project Prepared for Evolution Mining Ltd Final Report Authors: Grant Wells, Grace Wells Reviewers: Volker Framenau Submitted to: Marty Costello, Evolution Mining Ltd Version history Name Status Version Date G. & G. Wells Draft for client comments 1 23 June 2016 G. Wells Final 0 16 August 2016 ©Phoenix Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd 2016 The use of this report is solely for the Client for the purpose in which it was prepared. Phoenix Environmental Sciences accepts no responsibility for use beyond this purpose. All rights are reserved and no part of this report may be reproduced or copied in any form without the written permission of Phoenix Environmental Sciences or the Client. Phoenix Environmental Sciences Pty Ltd 1/511 Wanneroo Rd BALCATTA WA 6021 P: 08 9345 1608 F: 08 6313 0680 E: [email protected] Project code: 1116-EVO-EM-BOT Flora and vegetation assessment for the Edna May Greenfinch Project Prepared for Evolution Mining Ltd Contents CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................................ I LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................................... II LIST OF TABLES -

Evolution Mining Edna May Gold Mine

EVOLUTION MINING EDNA MAY GOLD MINE WESTONIA ENVIRONMENTAL NOISE ASSESSMENT OCTOBER 2017 OUR REFERENCE: 22374‐1‐17203 Rochdale Holdings Pty Ltd A.B.N. 85 009 049 067 trading as: HERRING STORER ACOUSTICS P.O. Box 219, Como, W.A. 6952 (08) 9367 6200 [email protected] Herring Storer Acoustics DOCUMENT CONTROL PAGE ENVIRONMENTAL NOISE ASSESSMENT WESTONIA Job No: 17203 Document Reference: 22374‐1‐17203 FOR EVOLUTION MINING DOCUMENT INFORMATION Author: Paul Daly Checked By: Tim Reynolds Date of Issue: 19 October 2017 REVISION HISTORY Revision Description Date Author Checked DOCUMENT DISTRIBUTION Electronic Copy No. Version No. Destination Hard Copy Copy Evolution Mining 1 1 Bella Bamford [email protected] Herring Storer Acoustics CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 2.0 MEASUREMENTS 1 3.0 CRITERIA 1 4.0 RESULT / DISCUSSION 3 5.0 CONCLUSION 5 APPENDICIES A Residential Location and Mine Plan Layouts B Graphical Data – Spectral Data Observed Night Measurements C Graphical Data – Continuous Monitoring Herring Storer Acoustics 1 Our ref: 22374‐1‐17203 1.0 INTRODUCTION Evolution Mining commissioned Herring Storer Acoustics (HSA) to undertake an acoustic study of the mining operations at the Edna May Gold Mine. The Edna May Gold Mine is situated approximately 320kms east of Perth and located approximately 2kms north of the town of Westonia. The mine and residential locations are shown in Appendix A, Figure 1. This assessment has been undertaken to analyse the noise emissions from the operations and to compare them to those previously measured. This report details the results of noise measurements of operations conducted over the period 3th to 18th October 2017. -

Chalice Gold Mines Limited Annual Information Form

CHALICE GOLD MINES LIMITED ANNUAL INFORMATION FORM September 28, 2018 GLOSSARY ...................................................................................................................................................................... 2 PRESENTATION OF INFORMATION ................................................................................................................................ 6 FORWARD-LOOKING INFORMATION ............................................................................................................................. 6 FINANCIAL INFORMATION AND ACCOUNTING PRINCIPLES .......................................................................................... 7 EXCHANGE RATES .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 TECHNICAL INFORMATION ............................................................................................................................................ 8 DESIGNATED FOREIGN ISSUER STATUS ......................................................................................................................... 8 CORPORATE STRUCTURE ............................................................................................................................................... 9 BUSINESS OF THE COMPANY ....................................................................................................................................... 11 RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ............................................................................................................................................ -

Legislative Council

Legislative Council Tuesday, 23 June 2009 THE PRESIDENT (Hon Barry House) took the chair at 3.30 pm, and read prayers. LANDFILL LEVY Statement by Minister for Environment HON DONNA FARAGHER (East Metropolitan — Minister for Environment) [3.32 pm]: I wish to advise the house that, as announced in the budget, the state government has decided to introduce a 300 per cent increase in landfill levy charges on 1 January 2010 to ensure certainty for local governments. Having received legal advice, the government has decided it is appropriate that prior to the proposed 300 per cent increase in levy charges taking effect, the Waste Avoidance and Resource Recovery Amendment Bill 2009 should occur. The government is confident that the legislation is valid and that it will provide for waste levy moneys to be used for both waste-related purposes and for the Department of Environment and Conservation to also utilise levy moneys for broader environmental and conservation purposes. Any funding matters will be dealt with by government as part of the midyear review process and the Western Australian environment will not be compromised. The government introduced the Waste Avoidance and Resource Recovery Amendment Bill 2009 into the Legislative Assembly on 18 June 2009. The landfill levy, in place since 1998, provides a financial disincentive to landfill and encourages the re-use or recycling of waste, which this government fully supports. Currently, landfill levy charges in Western Australia are well below those in other jurisdictions—for example, in New South Wales the equivalent levy is $46.70 per tonne. Even after the increase, Western Australian landfill levy rates will not be the highest in Australia. -

Western Australia Mineral and Petroleum Statistics Digest 2009-10

*RYHUQPHQWRI:HVWHUQ$XVWUDOLD 'HSDUWPHQWRI0LQHVDQG3HWUROHXP © MACARTHUR COAL LTD STATISTICS DIGEST 2009–10 STATISTICS © WOODSIDE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MINERAL AND PETROLEUM © RIO TINTO WESTERN AUSTRALIAN MINERAL AND PETROLEUM STATISTICS DIGEST 2009–10 CONTENTS FOREWORD ..........................................................................................................................................................3 1. EXPLORATION, MINERAL TITLES AND APPROVALS PROCESS .............................................................4 1.1 Minerals Exploration ...........................................................................................................4 1.2 Petroleum Exploration ........................................................................................................5 1.3 Mineral Titles......................................................................................................................5 1.4 Approvals Process ..............................................................................................................6 2. MINERAL AND PETROLEUM INDUSTRY 2009–10 REVIEW ...................................................................9 2.1 Overview ............................................................................................................................9 2.2 Iron Ore ............................................................................................................................14 2.3 Petroleum ........................................................................................................................24