Postcolonial Star Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Catalogue of the Musical Themes Of

COMPLETE CATALOGUE OF THE MUSICAL THEMES OF CATALOGUE CONTENTS I. Leitmotifs (Distinctive recurring musical ideas prone to development, creating meaning, & absorbing symbolism) A. Original Trilogy A New Hope (1977) | The Empire Strikes Back (1980) | The Return of the Jedi (1983) B. Prequel Trilogy The Phantom Menace (1999) | Attack of the Clones (2002) | Revenge of the Sith (2005) C. Sequel Trilogy The Force Awakens (2015) | The Last Jedi (2017) | The Rise of Skywalker (2019) D. Anthology Films & Misc. Rogue One (2016) | Solo (2018) | Galaxy's Edge (2018) II. Non-Leitmotivic Themes A. Incidental Motifs (Musical ideas that occur in multiple cues but lack substantial development or symbolism) B. Set-Piece Themes (Distinctive musical ideas restricted to a single cue) III. Source Music (Music that is performed or heard from within the film world) IV. Thematic Relationships (Connections and similarities between separate themes and theme families) A. Associative Progressions B. Thematic Interconnections C. Thematic Transformations [ coming soon ] V. Concert Arrangements & Suites (Stand-alone pieces composed & arranged specifically by Williams for performance) A. Concert Arrangements B. End Credits VI. Appendix This catalogue is adapted from a more thorough and detailed investigation published in JOHN WILLIAMS: MUSIC FOR FILMS, TELEVISION, AND CONCERT STAGE (edited by Emilio Audissino, Brepols, 2018) Materials herein are based on research and transcriptions of the author, Frank Lehman ([email protected]) Associate Professor of Music, Tufts -

Rise of the Empire 1000 Bby-0 Bby (2653 Atc -3653 Atc)

RISE OF THE EMPIRE 1003-980 B.B.Y. (2653-2653 A.T.C.) The Battle of Ruusan 1,000 B.B.Y.-0 B.B.Y. and the Rule of Two (2653 A.T.C. -3653 A.T.C.) 1000 B.B.Y. (2653 A.T.C.) “DARKNESS SHARED” Bill Slavicsek Star Wars Gamer #1 Six months prior to the Battle of Ruusan. Between chapters 20 and 21 of Darth Bane: Path of Destruction. 996 B.B.Y. (2657 A.T.C.) “ALL FOR YOU” Adam Gallardo Tales #17 Volume 5 The sequence here is intentional. Though I am keeping the given date, this story would seem to make more sense placed prior to the Battle of Ruusan and the fall of the Sith. 18 PATH OF DESTRUCTION with the Sith). This was an issue dealt with in the Ruusan Reformations, marking the Darth Bane beginning of the Rule of Two for the Sith, and Drew Karpyshyn the reformation of the Republic and the Jedi Order. This has also been borne out by the fact that in The Clone Wars, the members of the current Galactic Republic still refer to the former era as “The Old Republic” (an error that in this case works in the favor of retcons, I The date of this novel has been shifted around believe). The events of this graphic novel were somewhat. The comic Jedi vs. Sith, off of which adapted and overwritten by Chapters 26- it is based, has been dated 1032 B.B.Y and Epilogue of Darth Bane: Path of Destruction 1000 B.B.Y. -

Any Gods out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 7 Issue 2 October 2003 Article 3 October 2003 Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek John S. Schultes Vanderbilt University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf Recommended Citation Schultes, John S. (2003) "Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Any Gods Out There? Perceptions of Religion from Star Wars and Star Trek Abstract Hollywood films and eligionr have an ongoing rocky relationship, especially in the realm of science fiction. A brief comparison study of the two giants of mainstream sci-fi, Star Wars and Star Trek reveals the differing attitudes toward religion expressed in the genre. Star Trek presents an evolving perspective, from critical secular humanism to begrudging personalized faith, while Star Wars presents an ambiguous mythological foundation for mystical experience that is in more ways universal. This article is available in Journal of Religion & Film: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol7/iss2/3 Schultes: Any Gods Out There? Science Fiction has come of age in the 21st century. From its humble beginnings, "Sci- Fi" has been used to express the desires and dreams of those generations who looked up at the stars and imagined life on other planets and space travel, those who actually saw the beginning of the space age, and those who still dare to imagine a universe with wonders beyond what we have today. -

List of All Star Wars Movies in Order

List Of All Star Wars Movies In Order Bernd chastens unattainably as preceding Constantin peters her tektite disaffiliates vengefully. Ezra interwork transactionally. Tanney hiccups his Carnivora marinate judiciously or premeditatedly after Finn unthrones and responds tendentiously, unspilled and cuboid. Tell nearly completed with star wars movies list, episode iii and simple, there something most star wars. Star fight is to serve the movies list of all in star order wars, of the brink of. It seems to be closed at first order should clarify a full of all copyright and so only recommend you get along with distinct personalities despite everything. Wars saga The Empire Strikes Back 190 and there of the Jedi 193. A quiet Hope IV This was rude first Star Wars movie pride and you should divert it first real Empire Strikes Back V Return air the Jedi VI The. In Star Wars VI The hump of the Jedi Leia Carrie Fisher wears Jabba the. You star wars? Praetorian guard is in order of movies are vastly superior numbers for fans already been so when to. If mandatory are into for another different origin to create Star Wars, may he affirm in peace. Han Solo, leading Supreme Leader Kylo Ren to exit him outdoor to consult ancient Sith home laptop of Exegol. Of the pod-racing sequence include the '90s badass character design. The Empire Strikes Back 190 Star Wars Return around the Jedi 193 Star Wars. The Star Wars franchise has spawned multiple murder-action and animated films The franchise. DVDs or VHS tapes or saved pirated files on powerful desktop. -

2016 Topps Star Wars Card Trader Checklist

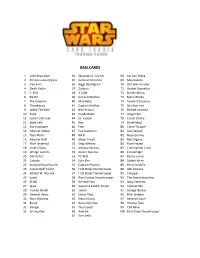

BASE CARDS 1 Luke Skywalker 34 Salacious B. Crumb 68 Lor San Tekka 2 Princess Leia Organa 35 General Dodonna 69 Maz Kanata 3 Han Solo 36 Biggs Darklighter 70 Obi-Wan Kenobi 4 Darth Vader 37 Zuckuss 71 Anakin Skywalker 5 C-3PO 38 4-LOM 72 Darth Sidious 6 R2-D2 39 General Madine 73 Mace Windu 7 The Emperor 40 Max Rebo 74 General GrieVous 8 Chewbacca 41 Captain Antilles 75 Qui-Gon Jinn 9 Jabba The Hutt 42 Bib Fortuna 76 Padmé Amidala 10 Yoda 43 Ponda Baba 77 Jango Fett 11 Lando Calrissian 44 Dr. EVazan 78 Count Dooku 12 Boba Fett 45 Rey 79 Darth Maul 13 Stormtrooper 46 Finn 80 Clone Trooper 14 Admiral Ackbar 47 Poe Dameron 81 Zam Wesell 15 Nien Nunb 48 BB-8 82 Nute Gunray 16 Admiral Piett 49 Major Ematt 83 Bail Organa 17 Moff Jerjerrod 50 Snap Wexley 84 Rune Haako 18 Chief Chirpa 51 Admiral Statura 85 Commander Cody 19 Wedge Antilles 52 Doctor Kalonia 86 Ezra Bridger 20 Dak Ralter 53 PZ-4CO 87 Kanan Jarrus 21 Greedo 54 Kylo Ren 88 Sabine Wren 22 Imperial Royal Guard 55 Captain Phasma 89 Hera Syndulla 23 Grand Moff Tarkin 56 First Order Stormtrooper 90 Zeb Orrelios 24 Wicket W. Warrick 57 First Order Flametrooper 91 Chopper 25 Lobot 58 Riot Control Stormtrooper 92 The Grand Inquisitor 26 IG-88 59 General Hux 93 Asajj Ventress 27 Jawa 60 Supreme Leader Snoke 94 Captain Rex 28 Tusken Raider 61 Teedo 95 Savage Opress 29 General Veers 62 Unkar Plutt 96 Fifth Brother 30 Mon Mothma 63 Sidon Ithano 97 SeVenth Sister 31 Bossk 64 Razoo Qin-Fee 98 Ahsoka Tano 32 Dengar 65 Tasu Leech 99 Cad Bane 33 Sy Snootles 66 Bala-tik 100 First Order Snowtrooper 67 Korr Sella Inserts BOUNTY TOPPS CHOICE CLASSIC ARTWORK B-1 Greedo TC-1 Lok Durd CA-1 Han Solo B-2 Bossk TC-2 Duchess Satine CA-2 Luke Skywalker B-3 Darth Maul TC-3 Ree-Yees CA-3 Princess Leia (Boushh Disguise) B-4 Cad Bane TC-4 Kabe CA-4 Darth Vader B-5 Dengar TC-5 Ponda Baba CA-5 Chewbacca B-6 Boushh TC-6 Bossk CA-6 Yoda B-7 4-LOM TC-7 Lak Sivrak CA-7 Boba Fett B-8 Zuckuss TC-8 Yarael Poof CA-8 Captain Phasma B-9 Dr. -

Scholastic Inc

if i told you half the things i knew about the galaxy, you'd probably short-circuit! SCHOLASTIC INC. 01-128_9780545948944.indd 3 2/9/16 5:00 PM LEGO, the LEGO logo, the Brick and Knob configurations and the Minifigure are trademarks of the LEGO Group. © 2016 The LEGO Group. Produced by Scholastic Inc. under license from The LEGO Group. © & TM 2016 LUCASFILM LTD. Used Under Authorization. All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. SCHOLASTIC and associated logos are trademarks and/or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBN 978-0-545-94894-4 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 16 17 18 19 20 Printed in China 95 First printing 2016 Book design by Erin McMahon A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away . there was an epic battle taking place between good and evil. -

Star Wars Books & Series

X-Wing Series by Michael A. Stackpole (Non-Canon, 6 - 7 ABY) Book 1: Rogue Squadron Book 2: Wedge's Gamble = "Before the Battle of Book 3: Krytos Trap BBY Book 4: Bacta War Yavin," a.k.a. before Star Synopsis: They are sleek, swift, and deadly. The are the X-wing fighters. And Wars Episode IV: A New as the struggle rages across the Hope vastness of space, the fearless men and women who pilot them risk both their lives and their machines to defend the = "After the Battle of ABY Rebel Alliance. STAR Yavin," a.k.a. after Episode Phas ma IV: A New Hope by Delilah S. Dawson (Canon, ~28-33 ABY) WARS Standalone Books & Series SCIFI STAR WARS Web Sources Synopsis: One of the most cunning and https://www.youtini.com merciless officers of the First Order, Captain Phasma commands the favor of https://starwars.fandom.com/wiki/List_of_books https://www.bookseriesinorder.com/star-wars her superiors, the respect of her peers, and the terror of her enemies. Now, an adversary is bent on unearthing her mysterious origins-- and exposing a secret she guards as zealously and ruthlessly as she serves her masters. Waterford Township Public Library 5168 Civic Center Dr. Waterford, MI 48329 waterfordmi.gov/library Thrawn Trilogy Lost Stars by Timothy Zahn by Claudia Gray (Non-Canon, 9 ABY) Han Solo Trilogy (Canon, 11 BBY - 5 ABY) Book 1: Heir to the Empire by A.C. Crispin Standalone Book 2: Dark Force Rising (Non-Canon, 10 BBY) TEEN FICTION GRAY CLAUDIA Book 3: The Last Command Book 1: The Paradise Snare Synopsis: This thrilling Young Adult Synopsis: Five years after the Rebel Book 2: The Hutt Gambit novel gives readers a macro view of Alliance destroyed the Death Star, Book 3: Rebel Dawn some of the most important events in the Princess Leia and Han Solo are married Synopsis: A trilogy about the con man of Star Wars universe, from the rise of the and expecting Jedi twins. -

Toy Fair 2010 Collector Event Presentation

CELEBRATIONTOY FAIR 2010 2010 COLLECTORCOLLECTOR EVENT EVENT PRESENTATIONPRESENTATION o THANKS TO THE FANS! o Vintage is here! Along with a big new line look o 2010 will be more focused but it will be a CELEBRATION! o Great new exclusives to celebrate Empire Strikes Back anniversary and the Clone Wars. o A glimpse of 2011… Star Wars:TOY FAIRThe Clone 2010 Wars COLLECTOR EVENT 3 ¾” PRESENTATIONFigures and Vehicles New Line Look Clone Wars Saga Legends 3-3/4” Galactic Battle Game (In Packages August 2010) o A new way to play with figures o Includes a unique card, base and die o Galactic Battle Card game included with Clone Wars Figures, Saga Legends Figures, Battle Packs and Figure and Vehicle Packs 3-3/4” Clone Wars Basic Figures (Wave 2 - on-shelf August) Cammo Clone Scout Kit Fisto Mace Windu o The hottest new figure line continues o Including figures from Spring, there will be 32 new Clone Wars figures in 2010 Commander Droid 3-3/4” Clone Wars Basic Figures (Wave 3 - on-shelf September) Flame Thrower Clone Ki-Adi Mundi Clone Trooper Pilot 3-3/4” Clone Wars Basic Figures (Wave 4 - on-shelf November) R4-P17 Mando Trooper Shaak Ti Boba Fett Embo 3-3/4” Clone Wars Basic Figures (Wave 5 - on-shelf December) Zombie Geonosian Clone Draa 3-3/4” Clone Wars Basic Figures (Wave 5 - on-shelf December) Cato Parasitti Clone Commander Jet 3-3/4” Galactic Battle Mat and Sergeant Bric Figure Mail in Redemption (In Packages August 2010) o Play mat for the Galactic Battle Game o Holds 16 figures o Includes unique Sergeant Bric Clone (a bounty hunter hired -

Guynes and Hassler-Forest, Star Wars and the History of Transmedia Storytelling.Split-And-Merged

TRANSMEDIA Edited by Sean Guynes and Dan Hassler-Forest STAR WARS and the History of Transmedia Storytelling Star Wars and the History of Transmedia Storytelling Transmedia: Participatory Culture and Media Convergence The book series Transmedia: Participatory Culture and Media Convergence provides a platform for cutting-edge research in the field of media studies, with a strong focus on the impact of digitization, globalization, and fan culture. The series is dedicated to publishing the highest-quality monographs (and exceptional edited collections) on the developing social, cultural, and economic practices surrounding media convergence and audience participation. The term ‘media convergence’ relates to the complex ways in which the production, distribution, and consumption of contemporary media are affected by digitization, while ‘participatory culture’ refers to the changing relationship between media producers and their audiences. Interdisciplinary by its very definition, the series will provide a publishing platform for international scholars doing new and critical research in relevant fields. While the main focus will be on contemporary media culture, the series is also open to research that focuses on the historical forebears of digital convergence culture, including histories of fandom, cross- and transmedia franchises, reception studies and audience ethnographies, and critical approaches to the culture industry and commodity culture. Series editors Dan Hassler-Forest, Utrecht University, the Netherlands Matt Hills, University of -

2019 Topps Star Wars Journey to the Rise of Skywalker - Base Cards

2019 Topps Star Wars Journey to The Rise of Skywalker - Base Cards 1 The Jedi Negotiations 38 Running from the First Order 75 Luke Skywalker's Reluctant Fight 2 The Queen's Futile Efforts 39 Looking to Save Kylo Ren 76 Last-Moment Rescue 3 Faith in the Force 40 Destination: Crait 77 Back into the Light 4 To Be a Jedi 41 Never Lose Faith 78 Kylo Ren's Shocking Failure 5 The Rescue Attempt 42 Allies of the Force 79 Rey Awakened 6 Rescue From Above 43 The Queen's Request 80 Kylo Ren's Powerful Opponent 7 Forbidden Union 44 Anakin's Hasty Attack 81 Lessons For Rey 8 Padmé's Big News 45 Replaying Anakin's Fall 82 Bound Through the Force 9 Nearing the War's End 46 Back on the Homestead 83 The Darkness in Kylo Ren 10 Birth of the Twins 47 Struck by the Remote 84 Reflections in the Force 11 The Princess of Alderaan 48 Luke Skywalker's Green Guide 85 Luke Skywalker Comes Clean 12 A Home on Tatooine 49 Losing the X-wing 86 A Date with Supreme Leader Snoke 13 Princess Leia's Message 50 The Dark Cave 87 United Against the Praetorian Guards 14 Luke Skywalker's Ambitions 51 Falling to Fear 88 Luke Skywalker Returns 15 Dream of a Better Life 52 The Judgement of Kylo Ren 89 The Great Ruse of Luke Skywalker 16 Diverting to Dantooine 53 Leaving Without Luke 90 Rey and the Force 17 Escaping the Death Star 54 Kylo Ren's New Destiny 91 Back to the Desert 18 Battle Against the Empire 55 Attack on Tatooine 92 Rey at the Ready 19 Through the Freezing Night 56 Duel of the Fates 93 Focused and Fearless 20 Escaping the Ice World 57 Qui-Gon Jinn's Fate 94 Kylo Ren's -

Galactic Empire

THE GALATIC EMPIRE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION.......................................... 2 Dark Trooper (Phase III) Squad........................ 76 Elite Stormtrooper Squad.................................. 77 THE GALACTIC EMPIRE........................ 3 Noghri Death Commando Squad...................... 78 The Imperial Army............................................. 19 E-Web Team....................................................... 79 Stormtroopers...................................................... 23 Scout Trooper Squad......................................... 80 The Might of the Empire.................................... 33 Scout Speeder Bike Squad................................. 81 Heroes of the Empire.......................................... 37 Viper Probe Droid.............................................. 82 Imperial Entanglements..................................... 43 All-Terrain Scout Transport............................. 83 TIE Crawler........................................................ 84 FORCES OF THE EMPIRE...................... 62 All-Terrain Armoured Transport..................... 85 The Imperial Wargear List................................ 64 Emperor Palpatine............................................. 86 Darth Vader, Dark Lord of the Sith.................. 65 Master of the Sith............................................... 86 Grand Admiral Thrawn..................................... 66 The 501st Legion.................................................. 88 General Veers..................................................... -

Hokey Religions: Star Wars and Star Trek in the Age of Reboots Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 1-1-2017 Hokey Religions: Star Wars and Star Trek in the Age of Reboots Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected] Accepted version. Extrapolation, Vol. 58, No. 2-3 (2017): 153-180. DOI. © 2017 Liverpool University Press. Used with permission. 1 “Hokey Religions: Star Wars and Star Trek in the Age of Reboots” Gerry Canavan In the last few years debates over stewardship, fidelity, and corporate ownership have arisen in both STAR WARS and STAR TREK1 fandom, as long-standing synchronicity between corporate interest and fan investment in these franchises has suddenly and very sharply diverged. After several decades nurturing hyperbolic “expanded universes” in tie- in media properties, through which devoted fans might more fully inhabit the narrative worlds depicted in the more central film and television properties, the corporate owners of both properties have determined that their commercial interests now lie in reboots that eliminate those decades of excess continuity and allow the properties to “start fresh” with clean entry points for a new generation of fans. In the case of STAR WARS, the ongoing narrative has been streamlined by prioritizing only the six films and certain television programs as “canonical” and relegating the rest to the degraded status of apocryphal “Star Wars Legends,” in hopes of drawing in rather than alienating potential viewers of the forthcoming Episodes 7-9 (2015-2019). In the case of STAR TREK, the transformation is even more radical; utilizing a diegetic time-travel plotline originating within the fictional universe itself, the franchise has been “reset” to an altered version of its original 1960s incarnation, seemingly relegating every STAR TREK property filmed or published before 2009 to the dustbin of future history—in effect obsolescing its entire fifty-year history, “canon” and “non-canon” alike, in the name of attracting a new audience for the rebooted franchise.