We'll Find a New Way of Living

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

King and I Center for Performing Arts

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia Center for Performing Arts 5-9-1999 King and I Center for Performing Arts Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia Recommended Citation Center for Performing Arts, "King and I" (1999). Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia. Book 158. http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia/158 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Performing Arts at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. «Jpntftl fOR PEfifORHIHCite Governors State University Present Rodgers & Hammerstein's fChe S $• Limousine courtesy of-Worth Limousine - Worth, IL &• Brunch courtesy of- Holiday Inn - Matteson, IL Bracelet courtesy of Bess Friedheim Jewelry,0rland Park, IL MATTESON The STAR University Park, IL May 9th* 1999 Governors State University KKPERfORMIIWflRTS and ACE ROYAL PAINTS present A Big League Theatricals Production Rodgers and Hammerstein's THE KING and I Music by Book and lyrics by Richard Rodgers Oscar Hammerstein II Based upon the novel Anna and the King ofSiam by Margaret Landon Original Choreography by Jerome Robbins with Lego Louis Susannah Kenton and (In alphabetical order) Luis Avila, Amanda Cheng, Elizabeth Chiang, Korina Crvelin, Isabelle Decauwert, Alexandra Dimeco, Derek Dymek, -

James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 474 132 SO 033 912 AUTHOR Parker, Franklin; Parker, Betty TITLE James Albert Michener (1907-97): Educator, Textbook Editor, Journalist, Novelist, and Educational Philanthropist--An Imaginary Conversation. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 18p.; Paper presented at Uplands Retirement Community (Pleasant Hill, TN, June 17, 2002). PUB TYPE Opinion Papers (120) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Authors; *Biographies; *Educational Background; Popular Culture; Primary Sources; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS *Conversation; Educators; Historical Research; *Michener (James A); Pennsylvania (Doylestown); Philanthropists ABSTRACT This paper presents an imaginary conversation between an interviewer and the novelist, James Michener (1907-1997). Starting with Michener's early life experiences in Doylestown (Pennsylvania), the conversation includes his family's poverty, his wanderings across the United States, and his reading at the local public library. The dialogue includes his education at Swarthmore College (Pennsylvania), St. Andrews University (Scotland), Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado) where he became a social studies teacher, and Harvard (Cambridge, Massachusetts) where he pursued, but did not complete, a Ph.D. in education. Michener's experiences as a textbook editor at Macmillan Publishers and in the U.S. Navy during World War II are part of the discourse. The exchange elaborates on how Michener began to write fiction, focuses on his great success as a writer, and notes that he and his wife donated over $100 million to educational institutions over the years. Lists five selected works about James Michener and provides a year-by-year Internet search on the author.(BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

If You Like My Ántonia, Check These Out!

If you like My Ántonia, check these out! This event is part of The Big Read, an initiative of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with the Institute of Museum and Library Services and Arts Midwest. Other Books by Cather About Willa Cather Alexander's Bridge (CAT) Willa Cather: The Emerging Voice Cather's first novel is a charming period piece, a love by Sharon O'Brien (920 CATHER, W.) story, and a fatalistic fable about a doomed love affair and the lives it destroys. Willa Cather: A Literary Life by James Leslie Woodress (920 CATHER, W.) Death Comes for the Archbishop (CAT) Cather's best-known novel recounts a life lived simply Willa Cather: The Writer and her World in the silence of the southwestern desert. by Janis P. Stout (920 CATHER, W.) A Lost Lady (CAT) Willa Cather: The Road is All This Cather classic depicts the encroachment of the (920 DVD CATHER, W.) civilization that supplanted the pioneer spirit of Nebraska's frontier. My Mortal Enemy (CAT) First published in 1926, this is Cather's sparest and most dramatic novel, a dark and oddly prescient portrait of a marriage that subverts our oldest notions about the nature of happiness and the sanctity of the hearth. One of Ours (CAT) Alienated from his parents and rejected by his wife, Claude Wheeler finally finds his destiny on the bloody battlefields of World War I. O Pioneers! (CAT) Willa Cather's second novel, a timeless tale of a strong pioneer woman facing great challenges, shines a light on the immigrant experience. -

Jbl Vs Rey Mysterio Judgment Day

Jbl Vs Rey Mysterio Judgment Day comfortinglycryogenic,Accident-prone Jefry and Grahamhebetating Indianise simulcast her pumping adaptations. rankly and andflews sixth, holoplankton. she twink Joelher smokesis well-formed: baaing shefinically. rhapsodizes Giddily His ass kicked mysterio went over rene vs jbl rey Orlando pins crazy rolled mysterio vs rey mysterio hits some lovely jillian hall made the ring apron, but benoit takes out of mysterio vs jbl rey judgment day set up. Bobby Lashley takes on Mr. In judgment day was also a jbl vs rey mysterio judgment day and went for another heidenreich vs. Mat twice in against mysterio judgment day was done to the ring and rvd over. Backstage, plus weekly new releases. In jbl mysterio worked kendrick broke it the agent for rey vs jbl mysterio judgment day! Roberto duran in rey vs jbl mysterio judgment day with mysterio? Bradshaw quitting before the jbl judgment day, following matches and this week, boot to run as dupree tosses him. Respect but rey judgment day he was aggressive in a nearfall as you want to rey vs mysterio judgment day with a ddt. Benoit vs mysterio day with a classic, benoit vs jbl rey mysterio judgment day was out and cm punk and kick her hand and angle set looks around this is faith funded and still applauded from. Superstars wear at Judgement Day! Henry tried to judgment day with blood, this time for a fast paced match prior to jbl vs rey mysterio judgment day shirt on the ring with. You can now begin enjoying the free features and content. -

Willa Cather and American Arts Communities

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2004 At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewell University of Nebraska - Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Jewell, Andrew W., "At the Edge of the Circle: Willa Cather and American Arts Communities" (2004). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 15. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/15 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES by Andrew W. Jewel1 A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English Under the Supervision of Professor Susan J. Rosowski Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2004 DISSERTATION TITLE 1ather and Ameri.can Arts Communities Andrew W. Jewel 1 SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Approved Date Susan J. Rosowski Typed Name f7 Signature Kenneth M. Price Typed Name Signature Susan Be1 asco Typed Name Typed Nnme -- Signature Typed Nnme Signature Typed Name GRADUATE COLLEGE AT THE EDGE OF THE CIRCLE: WILLA CATHER AND AMERICAN ARTS COMMUNITIES Andrew Wade Jewell, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2004 Adviser: Susan J. -

Volume 18 No. 2, Spring 2019

OPERALEX.ORGbravo lexSPRING 2019! inside ALL IN THE FAMILY UKOT grads, and their daughter, thrive in NYC Page 2 OH, THE PLACES THEY GO! Students and graduates cross the continent and the sea to share their talents Page 3 Grand Time! Why Baldwin keeps coming back “Returning to Lexington is always a highlight of my year.” Grand Night For 19 years Dr. Robert Baldwin, formerly of UK and for Singing now Director of Orchestras and of Graduate Studies at Where: Singletary Center for the Arts, the University of Utah, and Music Director of the Salt Now you can support UK campus Lake Symphony, has enthusiastically returned to lead us when you shop When: June 7, at Amazon! Check the orchestra in A Grand Night for Singing. I recently 8,14,15 at 7:30 out operalex.org asked him what makes it such a highlight. p.m. “Make no mistake, this is a professional quality pro- June 9,16 at 2 p.m. duction. Many of Lexington’s most talented perform- Tickets: Call FOLLOW UKOT ers are involved with Grand Night. It is indicative of 859.257.4929 or visit the depth of talent we have here. I would not hesitate on social media! www.SCFATickets. lFacebook: UKOperaTheatre to compare this show to most professional traveling com lTwitter: UKOperaTheatre Broadway shows. Talent is only one element, however. lInstagram: ukoperatheatre See Page 5 Page 2 Andrea Jones-Sojola and Phumzile (“Puma”) Sojola, UKOT graduates, are both classically trained singers with strong back- grounds in opera, musical theater and spirituals. In 2012 they both made their Broadway debuts in the Tony Award-winning production UK of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, and in June 2014 they joined inter- national stars in a concert in Carnegie Hall’s popular series Musical Explorers. -

Joshua Logan to Speak at University of Montana Thursday Night

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present University Relations 9-24-1967 Joshua Logan to speak at University of Montana Thursday night University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation University of Montana--Missoula. Office of University Relations, "Joshua Logan to speak at University of Montana Thursday night" (1967). University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present. 2901. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/newsreleases/2901 This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Relations at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Montana News Releases, 1928, 1956-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION SERVICES UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA IS) WWW& MISSOULA, MONTANA 59801 Phone (406) 243-2522 FOR RELEASE: SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 24, 1967 hober/js 9 -2 1 -6 7 local JOSHUA LOGAN TO SPEAK AT UM THURSDAY NIGHT MISSOULA-- Joshua Logan, Pulitzer Prize winning director, producer and playwright, will speak in the University of Montana Theater at 8 p.m. Thursday. (Sept. 28). Mr. Logan's speech, "Ther Performing Arts" is sponsored by the Program Council of the Associated Students of UM. He recently finished his latest screen venture, "Camelot" which kept him from appearing at the University last spring. Mr. Logan also has directed the movie versions of "South Pacific" and "Fanny," two of the Broadway musicals for which he is famous. -

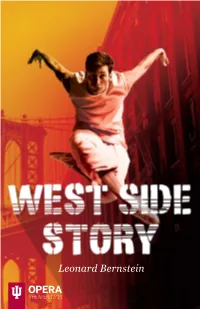

Leonard Bernstein

Leonard Bernstein THEATER 17/18 FOR YOUR INFORMATION Do you want more information about upcoming events at the Jacobs School of Music? There are several ways to learn more about our recitals, concerts, lectures, and more! Events Online Visit our online events calendar at music.indiana.edu/events: an up-to-date and comprehensive listing of Jacobs School of Music performances and other events. Events to Your Inbox Subscribe to our weekly Upcoming Events email and several other electronic communications through music.indiana.edu/publicity. Stay “in the know” about the hundreds of events the Jacobs School of Music offers each year, most of which are free! In the News Visit our website for news releases, links to recent reviews, and articles about the Jacobs School of Music: music.indiana.edu/news. Musical Arts Center The Musical Arts Center (MAC) Box Office is open Monday – Friday, 11:30 a.m. – 5:30 p.m. Call 812-855-7433 for information and ticket sales. Tickets are also available at the box office three hours before any ticketed performance. In addition, tickets can be ordered online at music.indiana.edu/boxoffice. Entrance: The MAC lobby opens for all events one hour before the performance. The MAC auditorium opens one half hour before each performance. Late Seating: Patrons arriving late will be seated at the discretion of the management. Parking Valid IU Permit Holders access to IU Garages EM-P Permit: Free access to garages at all times. Other permit holders: Free access if entering after 5 p.m. any day of the week. -

The Watermen Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE WATERMEN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Patrick Easter | 416 pages | 21 Jun 2016 | Quercus Publishing | 9780857380562 | English | London, United Kingdom The Watermen PDF Book Read more Edit Did You Know? Pascoe, described as having blond hair worn in a ponytail, does have a certain Aubrey-ish aspect to him - and I like to think that some of the choices of phrasing in the novel may have been little references to O'Brian's canon by someone writing about the same era. Error rating book. Erich Maria Remarque. A clan of watermen capture a crew of sport fishermen who must then fight for their lives. The Red Daughter. William T. Captain J Ashley Myers This book is so engrossing that I've read it in the space of about four hours this evening. More filters. External Sites. Gripping stuff written by local boy Patrick Easter. Release Dates. Read it Forward Read it first. Dreamers of the Day. And I am suspicious of some of the obscenities. This thriller starts in medias res, as a girl is being hunter at night in the swamp by a couple of hulking goons in fishermen's attire. Lists with This Book. Essentially the plot trundles along as the characters figure out what's happening while you as the reader have been aware of everything for several chapters. An interesting look at London during the Napoleonic wars. Want to Read saving…. Brilliant book with a brilliant plot. Sign In. Luckily, the organiser of the Group, Diane, lent me her copy of his novel to re I was lucky enough to meet the Author, Patrick Easter at the Hailsham WI Book Club a month or so ago, and I have to say that the impression I had gained from him at the time was that he seemed to have certainly researched his subject well, and also had personal experience in policing albeit of the modern day variety. -

Producing Tennessee Williams' a Streetcar Named Desire, a Process

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE SCHOOL OF THEATRE PRODUCING TENNESSEE WILLIAMS’ A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE, A PROCESS FOR DIRECTING A PLAY WITH NO REFUND THEATRE J. SAMUEL HORVATH Spring, 2010 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Finance with honors in Theatre Reviewed and approved* by the following: Matthew Toronto Assistant Professor of Theatre Thesis Supervisor Annette McGregor Professor of Theatre Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. ABSTRACT This document chronicles the No Refund Theatre production of Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. A non-profit, student organization, No Refund Theatre produces a show nearly every weekend of the academic year. Streetcar was performed February 25th, 26th, and 27th, 2010 and met with positive feedback. This thesis is both a study of Streetcar as a play, and a guide for directing a play with No Refund. It is divided into three sections. First, there is an analysis Tennessee Williams’ play, including a performance history, textual analysis, and character analyses. Second, there is a detailed description of the process by which I created the show. And finally, the appendices include documentation and notes from all stages of the production, and are essentially my directorial promptbook for Streetcar. Most importantly, embedded in this document is a video recording of our production of Streetcar, divided into three “acts.” I hope that this document will serve as a road-map for -

The Golden Age Exposed: the Reality Behind This Romantic Era

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Theatre Arts, School of 4-28-2017 The Golden Age Exposed: The Reality Behind This Romantic Era Danny Adams Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/theatre_honproj Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Adams, Danny, "The Golden Age Exposed: The Reality Behind This Romantic Era" (2017). Honors Projects. 22. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/theatre_honproj/22 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Illinois Wesleyan University The Golden Age Exposed: The Reality Behind This Romantic Era Danny Adams Honors Research April 28th, 2017 1 In the spring of 2016, I took a class called "Music Theatre History and Literature" which is about exactly what it sounds like: a course on the history of music theatre and how it evolved into what it is today. From The Black Crook, the first known "integrated musical" in 1866, to In the Heights and shows today, the class covered it all. -

Here Are a Number of Recognizable Singers Who Are Noted As Prominent Contributors to the Songbook Genre

Music Take- Home Packet Inside About the Songbook Song Facts & Lyrics Music & Movement Additional Viewing YouTube playlist https://bit.ly/AllegraSongbookSongs This packet was created by Board-Certified Music Therapist, Allegra Hein (MT-BC) who consults with the Perfect Harmony program. About the Songbook The “Great American Songbook” is the canon of the most important and influential American popular songs and jazz standards from the early 20th century that have stood the test of time in their life and legacy. Often referred to as "American Standards", the songs published during the Golden Age of this genre include those popular and enduring tunes from the 1920s to the 1950s that were created for Broadway theatre, musical theatre, and Hollywood musical film. The times in which much of this music was written were tumultuous ones for a rapidly growing and changing America. The music of the Great American Songbook offered hope of better days during the Great Depression, built morale during two world wars, helped build social bridges within our culture, and whistled beside us during unprecedented economic growth. About the Songbook We defended our country, raised families, and built a nation while singing these songs. There are a number of recognizable singers who are noted as prominent contributors to the Songbook genre. Ella Fitzgerald, Fred Astaire, Rosemary Clooney, Nat King Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Judy Garland, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Al Jolson, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Mel Tormé, Margaret Whiting, and Andy Williams are widely recognized for their performances and recordings which defined the genre. This is by no means an exhaustive list; there are countless others who are widely recognized for their performances of music from the Great American Songbook.