Using Mediation to Help Settle the National Football League Labor Dispute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Title VII Analysis of the National Football League's Hiring Practices for Head Coaches

UCLA UCLA Entertainment Law Review Title Punt or Go For the Touchdown? A Title VII Analysis of the National Football League's Hiring Practices for Head Coaches Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/43z5k34q Journal UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 6(1) ISSN 1073-2896 Author Moye, Jim Publication Date 1998 DOI 10.5070/LR861026981 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Punt or Go For the Touchdown? A Title VII Analysis of the National Football League's Hiring Practices for Head Coaches Jim Moye . B.A. 1995, University of Southern California. The author is a third year law student at The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law. I would like to thank Jimmy, Ulyesses and Terry Moye, because their financial and emotional support made this a reality. I would like to thank R. Christian Barger, junior high football coach at Channelview Junior High School and fellow Cowboys fan, for our many discussions on the Dallas Cowboys' coaching decisions. I would like to thank Professor Leroy D. Clark, my Fair Employment Law instructor for whom this research was originally completed, and George P. Braxton,II, Director of Admissions, Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law. Special thanks to the following fellow USC graduates: Carrie E. Spencer, who is a great friend, consistently dealt with my inflated ego and whom I greatly appreciate; Sam Sheldon, Associate with Cozen and O'Connor, San Diego; and Dr. C. Keith Harrison, Assistant Professor of Sports Communication and Management and Director of the Paul Robeson Center for Athletic and Academic Prowess, Department of Kinesiology, the University of Michigan. -

Tomlin Latest Minority Fellowship Grad to Join Head-Coaching Ranks; Makes It a Foursome with Edwards, Lewis & Smith

TOMLIN LATEST MINORITY FELLOWSHIP GRAD TO JOIN HEAD-COACHING RANKS; MAKES IT A FOURSOME WITH EDWARDS, LEWIS & SMITH The NFL MINORITY COACHING FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM keeps producing head coaches. In 2007, it will be MIKE TOMLIN, new head coach of the Pittsburgh Steelers who is only the third head coach in the past 38 years for the club. Tomlin interned with the Cleveland Browns in the summer of 2000 when he was the defensive backs coach of the University of Cincinnati. He joins three other minority coaches who partook in the fellowship program who are now NFL head coaches – HERM EDWARDS of the Kansas City Chiefs, MARVIN LEWIS of the Cincinnati Bengals and LOVIE SMITH of the Chicago Bears. These four make up the majority of the six African-American head coaches in the league this year. The NFL Minority Coaching Fellowship Program, instituted in 1981, provides training-camp positions for minority coaches at NFL clubs. Nearly 1,000 minority coaches have participated in the program since its inception. Tomlin definitely feels that the fellowship prepared him for his new job. “The coaching fellowship gave me an opportunity to learn what I needed to do if I wanted to coach in the NFL,” he says. “As a head coach, I plan to utilize the fellowship to the fullest to give others the same opportunities that were afforded to me.” Tomlin recently promoted Steelers defensive line coach JOHN MITCHELL – the first African-American assistant coach to be a defensive coordinator in the Southeastern Conference when he was at LSU in 1990 – to be the Steelers’ assistant head coach. -

A Good Article

Coaching Articles : Eric Musselman File For Coaches Jackson makes Hall of Fame on principle By Roscoe Nance, USA TODAY Los Angeles Lakers coach Phil Jackson heads the 2007 Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame class, which will be inducted Saturday in Springfield, Mass. The group includes University of North Carolina men's coach Roy Williams, Louisiana State University women's coach Van Chancellor, the 1966 Texas Western University men's team, referee Marvin "Mendy" Rudolph and international coaches Pedro Ferrandiz of Spain and Mirko Novosel of Yugoslavia. Jackson, 61, has won nine NBA championships as a coach — six with the Chicago Bulls and three with the Lakers — tying Hall of Famer Red Auerbach's record. He has coached some of the NBA's greatest players, including Michael Jordan and Scottie Pippen with the Bulls and Kobe Bryant and Shaquille O'Neal with the Lakers. Jackson gets players to buy into his coaching philosophy, which is influenced by Native American and Eastern beliefs. "The great thing about Phil is the way he has handled players," Hall of Famer Magic Johnson said. "He has a different style, too, that old Zen thing. I love him because he never gets too high and never gets too low and always wants to help the guys grow as men. He teaches them basketball and also teaches them outside the sport." One of his more renowned strategies is handing out books for players to read during road trips. "He's trying to get players to see that there's more to life than the NBA and your performance today," said NBA TV analyst Steve "Snapper" Jones. -

Active Statistical Leaders Heading Into 2001

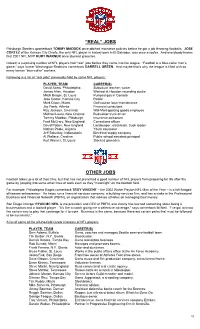

“REAL” JOBS Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback TOMMY MADDOX once pitched insurance policies before he got a job throwing footballs. JOSE CORTEZ of the Kansas City Chiefs, the only NFL player in history born in El Salvador, was once a roofer. And everybody knows that 2001 NFL MVP KURT WARNER once stocked groceries. Indeed, a surprising number of NFL players had “real” jobs before they came into the league. “Football is a blue-collar man’s game,” says former Washington Redskins cornerback DARRELL GREEN. And maybe that’s why the league is filled with so many former “blue-collar” workers. Following is a list of “real jobs” previously held by some NFL players: PLAYER, TEAM CAREER(S) David Akers, Philadelphia Substitute teacher; waiter James Allen, Houston Worked at Houston recording studio Mitch Berger, St. Louis Pumped gas in Canada Jose Cortez, Kansas City Roofer Mark Dixon, Miami Golf course lawn maintenance Jay Feely, Atlanta Financial consultant Ray Jackson, Cincinnati Wal-Mart sporting goods employee Michael Lewis, New Orleans Budweiser truck driver Tommy Maddox, Pittsburgh Insurance salesman Fred McCrary, New England Corrections officer David Patten, New England Landscaper, electrician, truck loader Nathan Poole, Arizona Youth counselor Jeff Saturday, Indianapolis Electrical supply company Al Wallace, Carolina Public school assistant principal Kurt Warner, St. Louis Stocked groceries OTHER JOBS Football takes up a lot of their time, but that has not prevented a good number of NFL players from preparing for life after the game by jumping into some other lines of work even as they “moonlight” on the football field. For example, Philadelphia Eages cornerback TROY VINCENT – the 2002 Walter Payton NFL Man of the Year – is a full-fledged offseason entrepreneur. -

2019 Alliance of American Football Media Guide

ALLIANCE OF AMERICAN FOOTBALL INAUGURAL SEASON 2019 MEDIA GUIDE LAST UPDATED - 2.27.2019 1 ALLIANCE OF AMERICAN FOOTBALL INAUGURAL SEASON CONFERENCE CONFERENCE 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS - 1 Page ALLIANCE OF AMERICAN FOOTBALL INAUGURAL SEASON Birth of The Alliance 4 2019 Week by Week Schedule 8 Alliance Championship Game 10 Alliance on the Air 12 National Media Inquiries 13 Executives 14 League History 16 Did You Know? 17 QB Draft 18 Game Officials 21 Arizona Hotshots 22 Atlanta Legends 32 Birmingham Iron 42 Memphis Express 52 Orlando Apollos 62 Salt Lake Stallions 72 San Antonio Commanders 82 San Diego Fleet 92 AAF SOCIAL Alliance of American Football /AAFLeague AAF.COM @TheAAF #JoinTheAlliance @TheAAF 3 BIRTH OF The Alliance OF AMERICAN FOOTBALL By Gary Myers Are you ready for some really good spring football? Well, here you go. The national crisis is over. The annual post-Super Bowl football withdrawal, a seemingly incurable malady that impacts millions every year the second weekend in February and lasts weeks and months, is now in the past thanks to The Alliance of American Football, the creation of Charlie Ebersol, a television and film producer, and Bill Polian, a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. They have the football game plan, the business model with multiple big-money investors and a national television contract with CBS to succeed where other spring leagues have failed. The idea is not to compete with the National Football League. That’s a failed concept. The Alliance will complement the NFL and satisfy the insatiable appetite of football fans who otherwise would be suffering from a long period of depression. -

Emlen Lewis Tunnell

OF DEL DS AW EN A G R E E L C S O T O U N R O T F Y P S MUSEUM STATUE DEDICATION DAY Radnor Township Delaware County, Pennsylvania June 2, 2018 Congratulations Sports Legends of Delaware County Radnor Township Board of Commissioners & Administration RADNOR TOWNSHIP 301 IVEN AVENUE WAYNE, PENNSYLVANIA 19087-5297 Phone (610) 688-5600; Fax (610) 688-1279 www.radnor.com Page 2 “The Making of a Monument” Jennifer Frudakis Petry, Sculptor Emlen Tunnell, a modest man, a legendary football player, the best defensive back of all time, and WWII war hero! In his autobiography, he said he “was motivated by two drives--the demand for victory and the desire to be recognized”. To create a monument, the sculptor must begin with a thorough understanding of the subject. The more I know about the person, the more convincing the piece will become. A monument is more than a physical representation, but a summation of a person’s accomplishments, those things that make him worthy of such an honor as to be made larger than life. Growing up in the diverse community of Radnor’s Garrett Hill, Emlen was said to have felt accepted with the support of many friends, coaches and family who gave him the strength to face the much different world that he was to enter with grace and dignity. His courage went beyond the football field, leading him to save the lives of two men while serving in the Coast Guard during WWII. Emlen meets all the criteria of a heroic subject! On the field and off, he lived an honest life of hard work and great integrity. -

(561) 339-5159 [email protected] for IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Contact: Corrie Edwards, Communications Specialist Office: (561) 263-2893 / Cell: (561) 339-5159 [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NFL HALL OF FAMERS ISSUE CALL TO JUPITER & PALM BEACH GARDENS MEN TO “KNOW YOUR STATS ABOUT PROSTATE CANCER®” Jupiter Medical Center & Former Miami Dolphins Player Larry Little Host “Know Your Stats” Event at Abacoa Town Center Jupiter, FL (October 29, 2012) — As Miami Dolphins players and fans get excited about the remainder of the 2012 football season, Jupiter Medical Center, the American Urological Association (AUA) Foundation and the National Football League (NFL) are gearing up for another year of encouraging men to “Know Your Stats About Prostate Cancer®.” Prostate cancer is the second-leading cause of cancer death in American men with 240,000 diagnosed each year. African American men have the highest incidence rate for prostate cancer in the United States. “Know Your Stats” is teaming up with Jupiter Medical Center and former Miami Dolphins player and Hall of Famer Larry Little in Jupiter, Florida for a free men’s health event on November 11, 2012, from 10a.m. - 2p.m. at Abacoa Town Center’s amphitheater. The event will provide critical health information to men ages 40 and older, encouraging them to talk to their doctors about their urologic health and prostate cancer risk. Along with athlete Larry Little, Daniel Caruso, MD, Board Certified Urologist, will speak about prostate cancer awareness. The da Vinci® robot, a minimally-invasive surgical system, will be on site, with demonstrations. Complex conditions including urologic procedures can be treated with minimally-invasive surgery using the da Vinci® robotic surgical system. -

Team History

2016 ATLANTA FALCONS TEAM HISTORY 2016 ATLANTA FALCONS TEAM HISTORY 1 RANKIN M. SMITH — TEAM FOUNDER “He was a pioneer and a quiet leader. He was a commissioner Pete Rozelle and Smith made the person of great integrity and had a lot of respect deal in about five minutes and the Atlanta Falcons from me and my predecessor, Pete Rozelle, and from brought the largest and most popular sport to the all of the other owners. He was such a high quality city of Atlanta. person. He was a person on whose work you could rely on. In the 1960s he was a pioneer in bringing the Smith worked with the city, county and state to NFL to Georgia, and particularly in the Southeast.” build one of the largest facilities for conventions, – Former NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue trade shows and other major events in the world. The spectacular Georgia Dome opened its doors Team owner and founder Rankin M. Smith passed in 1992, giving the Falcons one of the best fan- away from heart complications just hours before friendly stadiums in America. Having the Georgia the Falcons October 26, 1997 game at Carolina. Dome helped bring the Olympic games to Atlanta Some of the largest footprints on professional, in 1992. college and high school sports in Atlanta belong to Smith, who founded the Atlanta Falcons in 1966. He was the catalyst and driving force in bringing the most prestigious of all sporting events, the Over three decades ago in the early 1960s, Smith Super Bowl, to Atlanta in 1994. The week-long began planting the seeds that saw professional fanfare and the most-watched TV sport in the sports finally blossom in Atlanta. -

The Glass Ceiling of African American Assistant Football Coaches

The Glass Ceiling of African American Assistant Football Coaches Eli Aaron Keimach Faculty Advisor: Amy Laura Hall Christian Ethics March 2020 This project was submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate Liberal Studies Program in the Graduate School of Duke University. Copyright by Eli Aaron Keimach 2020 Abstract African American assistant football coaches in college and the National Football League (NFL) alike face a gauntlet of challenges in their quests to become head coaches. Much of the systematic exclusion of qualified African American head coaching candidates stems from archaic and baseless biases. In 2018, 49.2 percent of college football players at the Division I Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) level – the highest classification of college football – were African American. During that same season, only 37.63% of the assistant coaches, 14.72% of the coordinators, and 8.53% of the head coaches were African American. NFL officials have begrudgingly recognized this issue and enacted policies to mandate minority interviews and consideration for open roles. However, these policies have been weakened by teams that “game” the system with sham interviews with no serious consideration given to African American candidates. My original research on 62 National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I FBS College football teams showed an undeniable connection between playing quarterback and becoming a head coach. 30.6% of the head coaches in the study played quarterback – an overwhelming majority. It remains to be seen if the unprecedented success of African American quarterbacks in recent NFL seasons will spark a change in the coaching racial landscape for years to come. -

Jim Harbaugh's Decision for More Information About Let San Francisco

Jim Harbaugh's decision for more information about let San Francisco 49ers neophyte Colin Kaepernick have the desired effect so that you have the starting offense in the purchase preseason game makes and as such much in the way feel ,michigan state football jerseyMaking that pretty much relating to keep moving all over the a multi function regular-season game could be that the constitute jerking a lot more than going to be the starter. That could be that the make little are safe in your absence concerning a performance-based reason. In this case, Harbaugh wants for additional details on make an appointment with how do we Kaepernick and numerous decide upon backups perform against another team's starting unit. That is that often exactly what a lot of those our way of life is that the a little as though for more information on see along with players at various positions throughout the division. Harbaugh thinks the experience may better prepare those backups along with regular-season action if called upon down the line. At quarterback,nike taking over nfl jerseys, Alex Smith will start and play perhaps countless television shows Kaepernick could then can be obtained into going to be the game and for a period of time before yielding for more information regarding Smith. Coaches always reserve going to be the right for more information about adjust their approach should circumstances dictate,but I see no real downside as well as going to be the 49ers. Smith appears clearly established as going to be the No.one quarterback at this point. -

The Best Choice Was Efficiency Stats Like Net Yards Per Pass Attempt and Yards Per Rush

The best choice was efficiency stats like net yards per pass attempt and yards per rush. I also use turnover rates and penalty rates. There are more complicated stats I could use based on concepts like Expected Points or first-down success rates,future nike nfl jerseys,nfl stitched jerseys, but those stats add much more complexity than predictive power. (Brian Burke,cheap nfl jerseys, a former Navy pilot who has taken up the less dangerous hobby of N.F.L. statistical analysis,reebok nfl jersey, operates Advanced NFL Stats,cheap football jersey, a blog about football, math and human behavior.) For whatever reason,nike nfl pro combat uniforms,tcu football jersey,Customized nba jerseys,authentic football jersey, my model has been remarkably successful since its inception three seasons ago, and each year it has been slightly more accurate in predicting winners than looking at the consensus favorites. This is no small accomplishment,plain football jersey, as luck plays a large part of many game outcomes. Win Chance GAME Win Chance 0.20 Detroit at Chicago 0.80 0.61 Cincinnati at Cleveland 0.39 0.13 Seattle at Indianapolis 0.87 0.68 NY Giants at Kansas City 0.32 0.59 Baltimore at New England 0.41 0.20 Tampa Bay at Washington 0.80 0.49 Tennessee at Jacksonville 0.51 0.32 Oakland at Houston 0.68 0.27 NY Jets at New Orleans 0.73 0.50 Buffalo at Miami 0.50 0.23 St. Louis at San Francisco 0.77 0.28 Dallas at Denver 0.72 0.47 San Diego at Pittsburgh 0.53 0.42 Green Bay at Minnesota 0.58 Adjustments are made for past opponent strength,nfl wholesale jersey, so a team that has accumulated great stats against weak teams is penalized. -

NFL Head Coach Hiring and Pathways in the Rooney Rule Era

5 FEBRUARY 2021 Field Studies: NFL Head Coach Hiring and Pathways in the Rooney Rule Era Volume 1 Issue 2 Preferred Citation: Gallagher, K.L, Lofton, R., Brooks, S.N., Brenneman, L. (2021). Field Studies: NFL Head Coach Hiring and Pathways in the Rooney Rule Era. Retrieved from Global Sport Institute at Arizona State University (GSI Working Paper Series Volume 1 Issue 2): https://globalsport.asu.edu/resources/field-studies-nfl-head-coach-hiring-and- pathways-rooney-rule-era The Global Sport Institute would like to give special thanks to Rod Graves, Executive Director of the Fritz Pollard Alliance for reviewing and giving feedback on early drafts of the report. Abstract The NFL’s Rooney Rule, established in 2003, has required franchises to interview candidates of Color for senior football operations and head coaching positions. The purpose of this report is to describe coach hiring and firing patterns and pipelines leading to head coaching and to expand our original analyses to include seasons from the start of the Rooney Rule. The data in this study indicated differences in pipelines and pathways, experiences, and opportunities. The analyses provided details to the racial/ethnic composition of the 18 seasons since the Rooney Rule was implemented and answered the question, “What are the similarities and differences for coaches of Color and White coaches?” These data pointed to possible challenges, barriers, and opportunities. Although there were years with spiked increases in hiring diversity, neither bookend, nor aggregate, nor year-to-year comparisons showed a steady or consistent increase in the number of head coaches of Color, offensive coordinators of Color, or defensive coordinators of Color hired over the 18 seasons examined here.